Beginnings and Beyond Foundations in Early Childhood Education 9th Edition Gordon Solutions Manual

Beginnings and Beyond Foundations in Early Childhood Education 9th Edition Gordon Solutions Manual

Beginnings and Beyond Foundations in Early Childhood Education 9th Edition Gordon Solutions Manual

![—To make clear what I have said in this chapter, it will perhaps be

well to give two illustrations drawn from the Domesday Book

(eleventh century) and from bailiffs’ accounts of a later period (end

of thirteenth century).

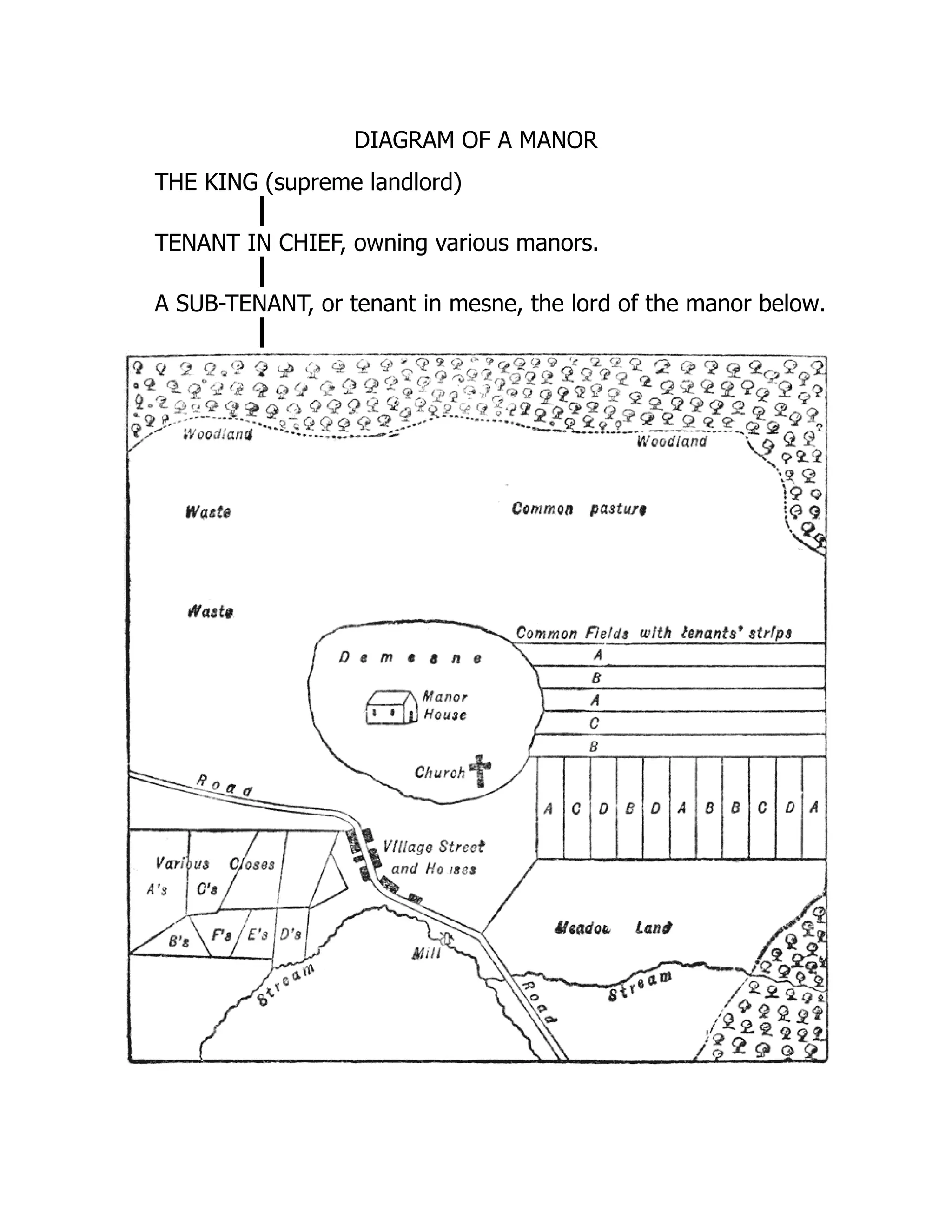

First we will take a manor in Warwickshire in the Domesday

Survey (1089)—Estone, now Aston, near Birmingham. It was one of

a number belonging to William, the son of Ansculf, who was tenant

in chief, but had let it to one Godmund, a sub-tenant in mesne. The

Survey runs: “William Fitz-Ansculf holds of the King Estone, and

Godmund of him. There are 8 hides.

11

The arable employs 20

ploughs; in the demesne the arable employs 6 ploughs, but now

there are no ploughs. There are 30 villeins with a priest, and 1

bondsman, and 12 bordars [i.e. cottars]. They have 18 ploughs. A

mill pays 3 {17} shillings. The woodland is 3 miles long and half a mile

broad. It was worth £4; now 100 shillings.”

11 A hide varied in size, and was (after the Conquest) equal to a

carucate, which might be anything from 80 to 120 or 180 acres. Perhaps

120 is a fair average, though some say 80.

Here we have a good example of a manor held by a sub-tenant,

and containing all the three classes mentioned in § 4 of this chapter

—villeins, cottars, and slaves (i.e. bondsmen). The whole manor

must have been about 5000 acres, of which 1000 were probably

arable land, which was of course parcelled out in strips among the

villeins, the lord, and the priest. As there were only 18 ploughs

among 30 villeins, it is evident some of them at least had to use a

plough and oxen in common. The demesne land does not seem to

have been well cultivated by Godmund the lord, for there were no

ploughs on it, though it was large enough to employ six. Perhaps

Godmund, being an Englishman, had been fighting the Normans in

the days of Harold, and had let it go out of cultivation, or perhaps

the former owner had died in the war, and Godmund had rented the

land from the Norman noble to whom William gave it.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/11021-250329221548-0f1ce1e3/75/Beginnings-and-Beyond-Foundations-in-Early-Childhood-Education-9th-Edition-Gordon-Solutions-Manual-10-2048.jpg)

![§ 10. Cuxham Manor in the eleventh and thirteenth

centuries

—Our second illustration can be described at two periods of its

existence—at the time of Domesday and 200 years later. It was only

a small manor of some 490 acres, and was held by a sub-tenant

from a Norman tenant in chief, Milo Crispin. It is found in the

Oxfordshire Domesday, in the list of lands belonging to Milo Crispin.

The Survey says: “Alured [the sub-tenant] now holds 5 hides for a

manor in Cuxham. Land to 4 ploughs; now in the demesne, 2

ploughs and 4 bondsmen. And 7 villeins with 4 bordars have 3

ploughs. There are 3 mills of 18 shillings; and 18 acres of meadow.

It was worth £3, now £6.” Here, again, our three classes of villeins,

cottars or bordars, and slaves are represented. The manor was

evidently a good one, for though smaller than Estone it {18} was

worth more, and has three mills and good meadow land as well.

Now, by the end of the thirteenth century this manor had passed

into the hands of Merton College, Oxford, which then represented

the lord, but farmed it by means of a bailiff. Professor Thorold

Rogers gives us a description of it,

12

drawn from the annual accounts

of this bailiff, which he has examined along with a number of others

from other manors. We find one or two changes have taken place,

for the bondsmen have entirely disappeared, as indeed they did in

less than a century after the Conquest all through the land. The

number of villeins and bordars has increased. There are now 13

villeins and 8 cottars, and 1 free tenant. There is also a prior, who

holds land (6 acres) in the manor but does not live in it; also two

other tenants, who do not live in the manor, but hold “a quarter of a

knight’s fee” (here some 40 or 50 acres)—a knight’s fee comprising

an area of land varying from 2 hides to 4 or even 6 hides, but in any

case worth some £20. As the Cuxham land was good, the quantity

necessary for the valuation of a fee would probably be only the small

hide or carucate of 80 acres, and the quarter of it of course 20 acres

or a little more. The 13 serfs hold 170 acres, but the 8 cottars only](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/11021-250329221548-0f1ce1e3/75/Beginnings-and-Beyond-Foundations-in-Early-Childhood-Education-9th-Edition-Gordon-Solutions-Manual-11-2048.jpg)