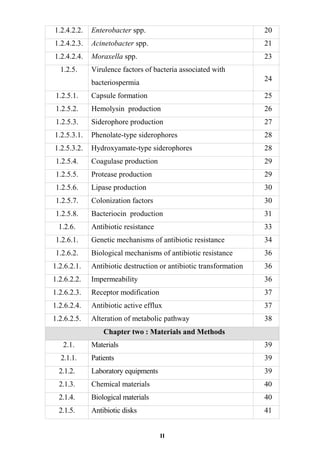

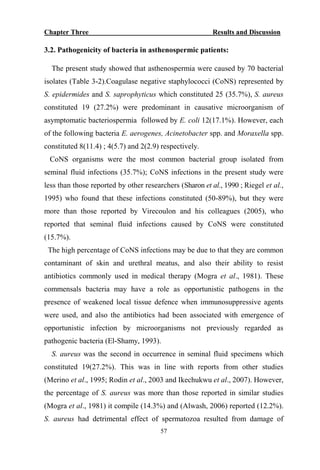

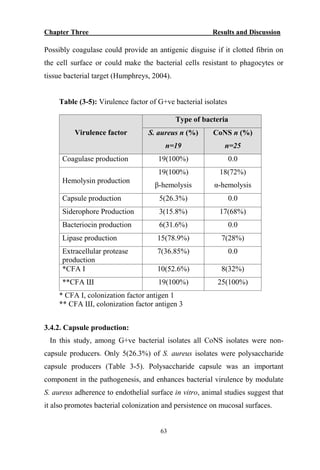

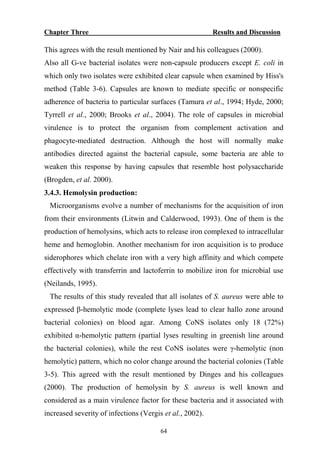

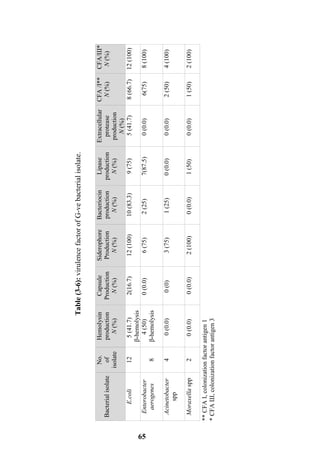

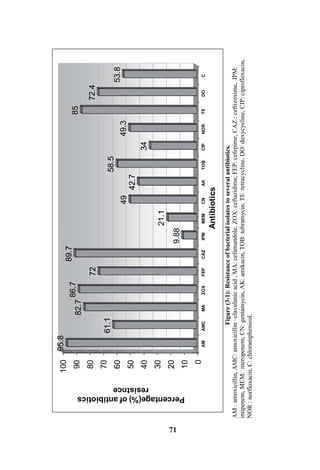

The document discusses bacteriospermia, a condition characterized by the presence of bacteria in seminal fluid, which is linked to male infertility, particularly asthenospermia. It includes an extensive literature review, highlighting the impact of bacterial infection on sperm function and various male infertility types. The work aims to investigate the relationship between bacteriospermia and leukocytospermia in infertile men and to identify common uropathogenic bacterial species along with their virulence factors and antibiotic resistance patterns.

![References

128

Rahal, J. (2006). Novel antibiotic combinations against infections with almost

completely resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter

species. Clin. Infect. Dis., 43(2):95–99.

Rajasekaran, M., Hellstrom W. J., Naz R. K., and Sikka S.C.(1995). Oxidative

stress and interleukins in seminal plasma during

leukocytospermia. Fertil. Steril., 64:166-171.

Rajesh, B. and Rutten I. (2004). Essential medical microbiology. 3rd ed. New

Delhi–Indian.

Raymond, K. N., Dertz E. A. and Kim S. S. (2003). Enterobactin: an archetype

for microbial iron transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. , 100:

3584-3588.

Raz, R., Colodner R. and Kunin C. M. (2005). Who are you -Staphylococcus

saprophyticus? CID [serial online]; 40:896-898.

Rehewy, M. S. E., Hafez E. S. E., Thomas A. and Brown W. J. (1979).

Aerobic and anaerobic bacterial flora in semen from fertile and

infertile groups of men. Arch. Andrology, (2): 238-263.

Reichart, M., Kahane I. and Bartoov B. (2000).In Vivo and In Vitro

Impairment of Human and Ram Sperm Nuclear Chromatin

Integrity by Sexually Transmitted Ureaplasma urealyticum.

Infect. Biol .Reprod. 63:1041-1048.

Reichart, M., Kahane I. and Bartoov B. (2001). Dual energy metabolism-

dependent effect of Ureaplasma urealyticum infection on sperm

activity. J. Androl., 22:404-412.

Riegel, P., Ruimy R., Briel D., Prevost G., Jehl F., Bimet F., Christen R. and

Monteil H. (1995). Corynebacterium seminali sp. Nov., new

species associated with genital infection in male patients. J.

Clinic. Microbiol., 33(9) .p. 2244-2249.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bacteriospermia-978-3-659-34491-6-160718201731/85/Bacteriospermia-145-320.jpg)