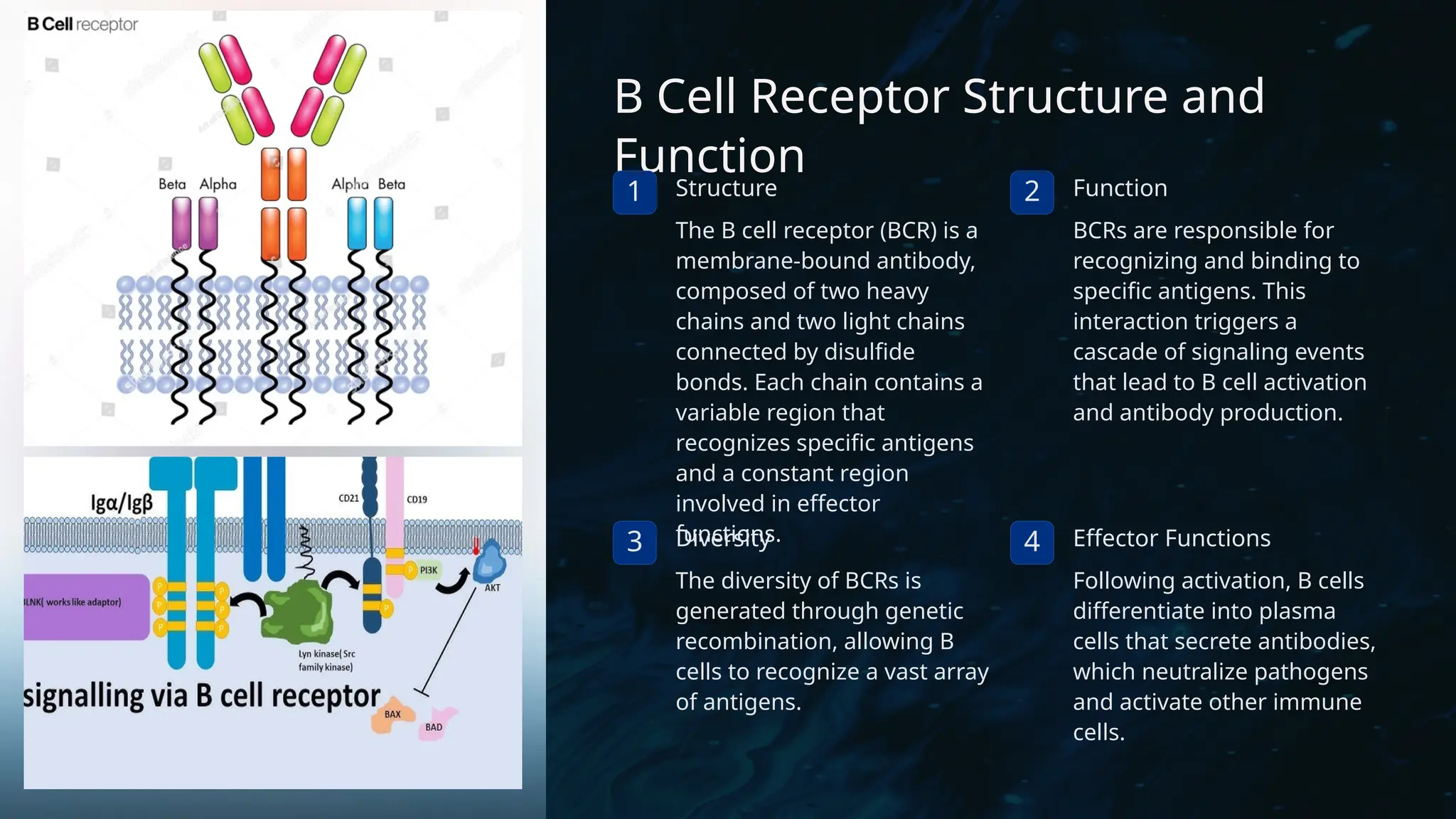

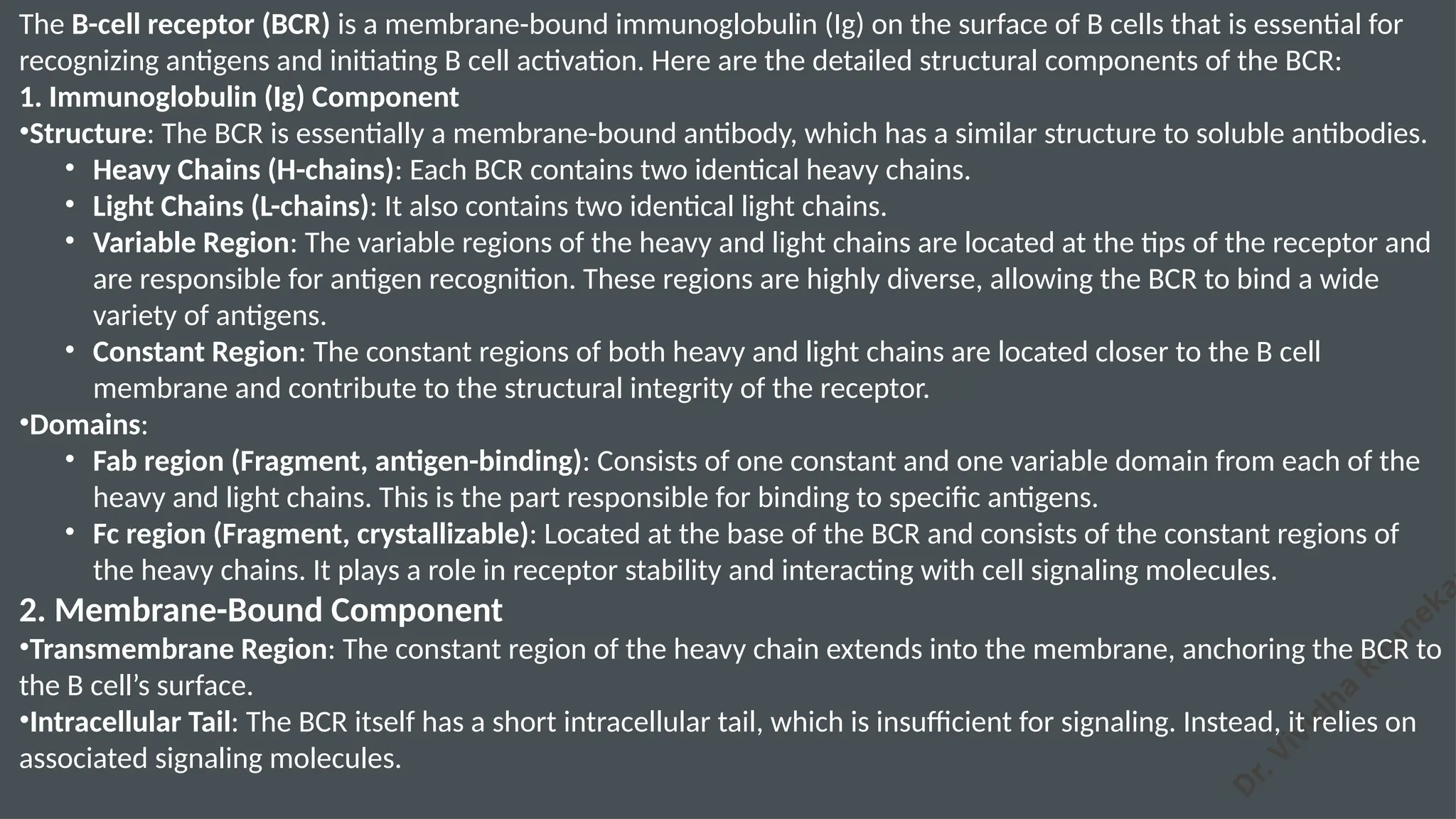

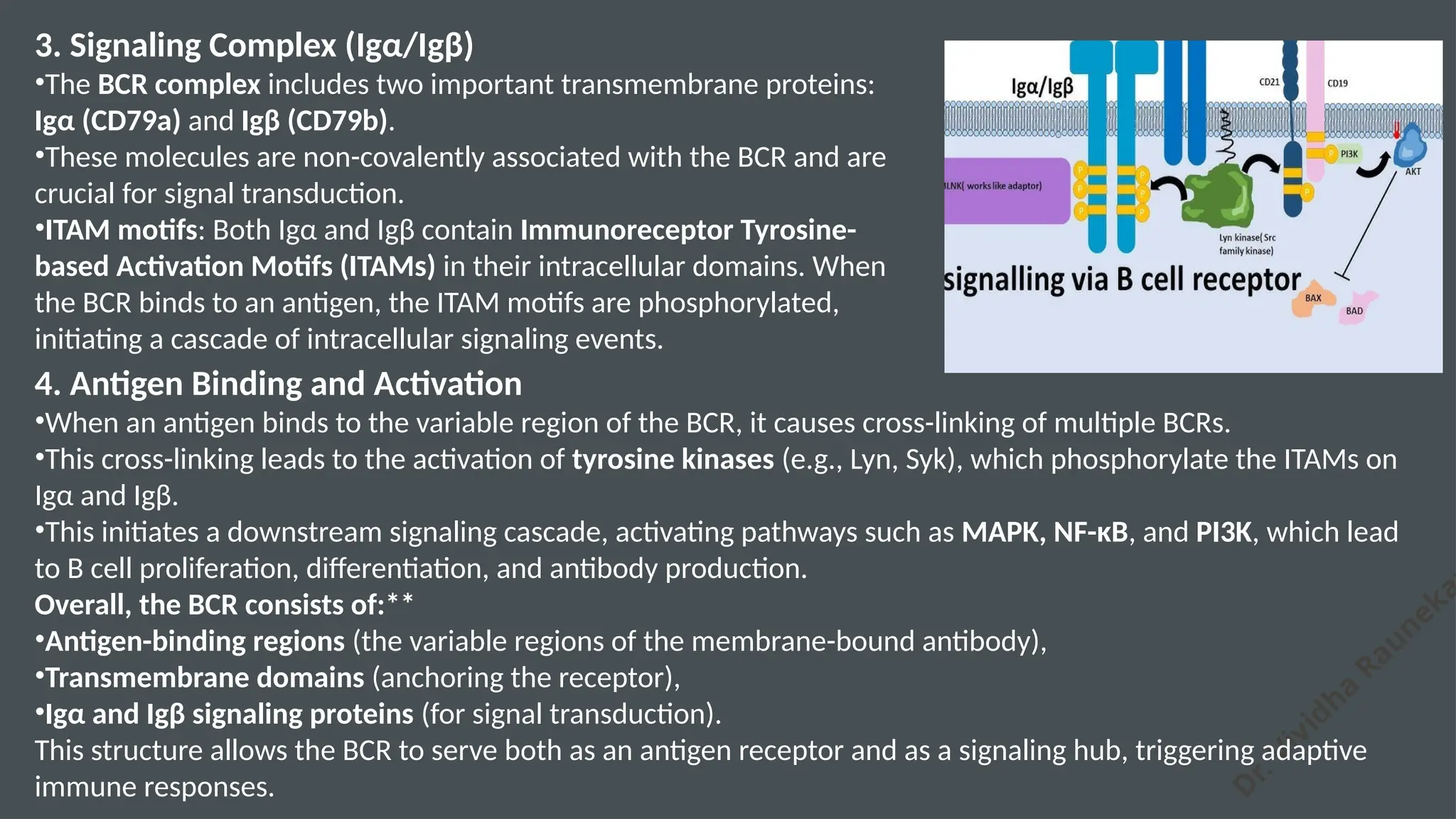

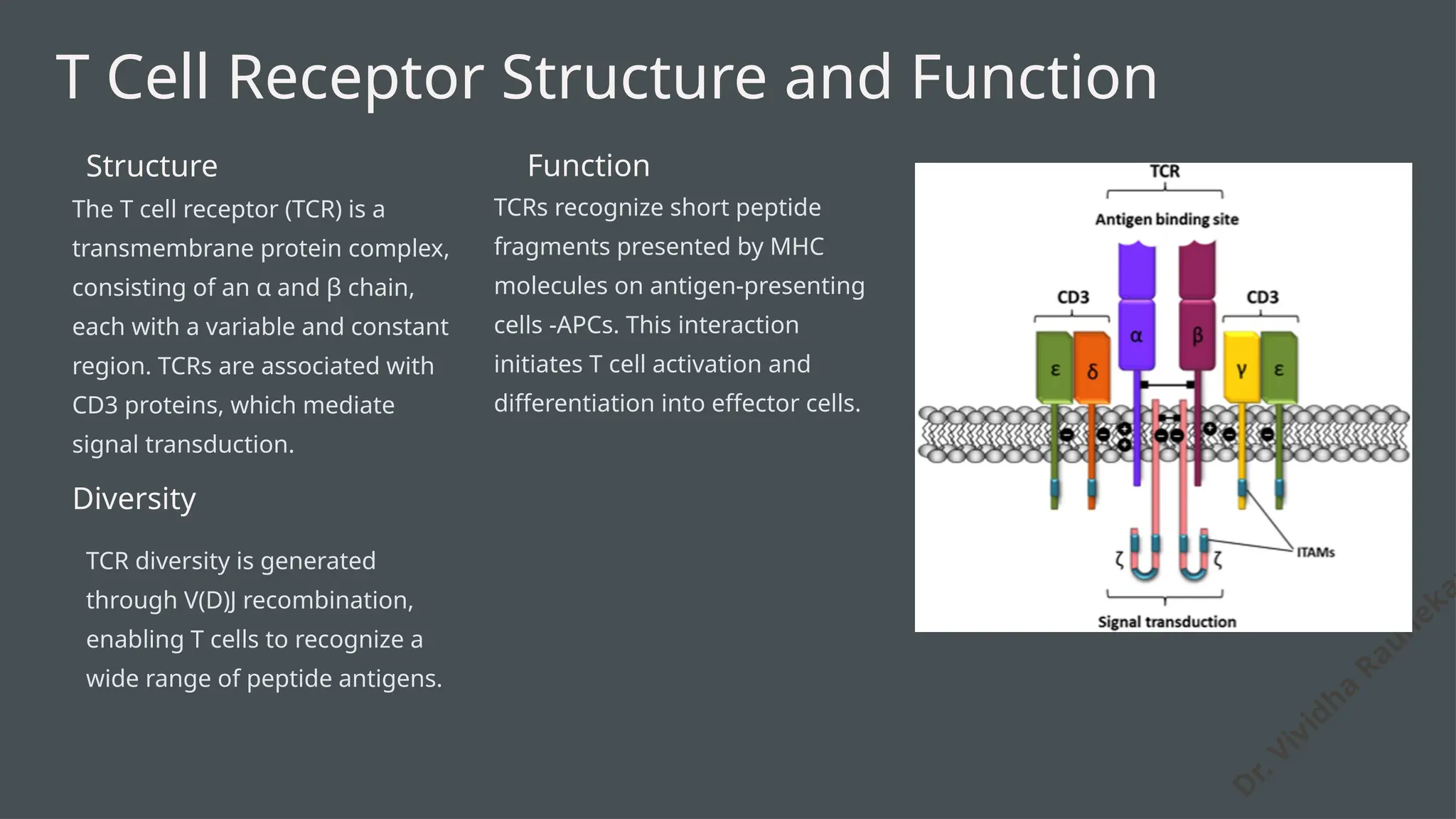

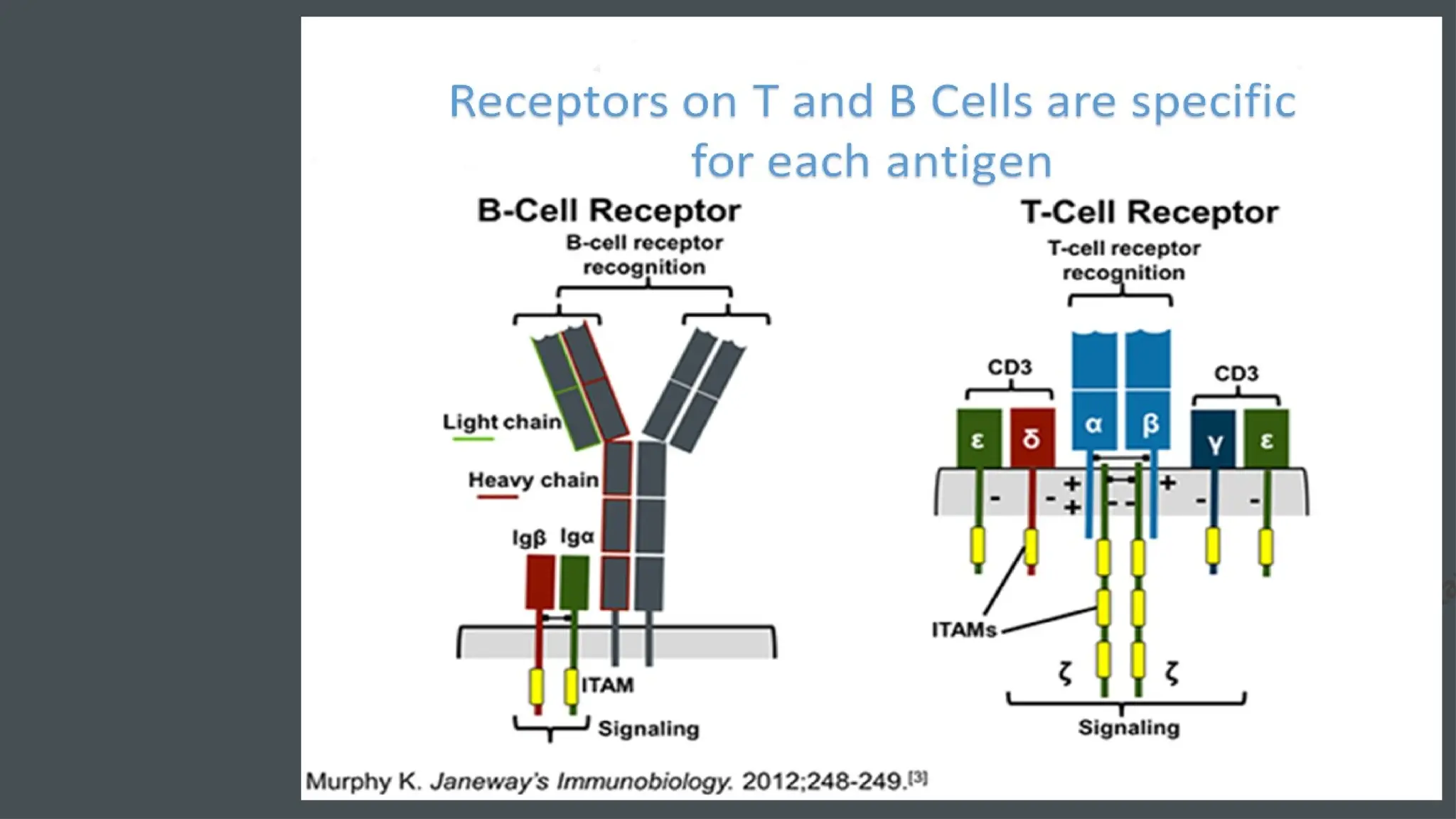

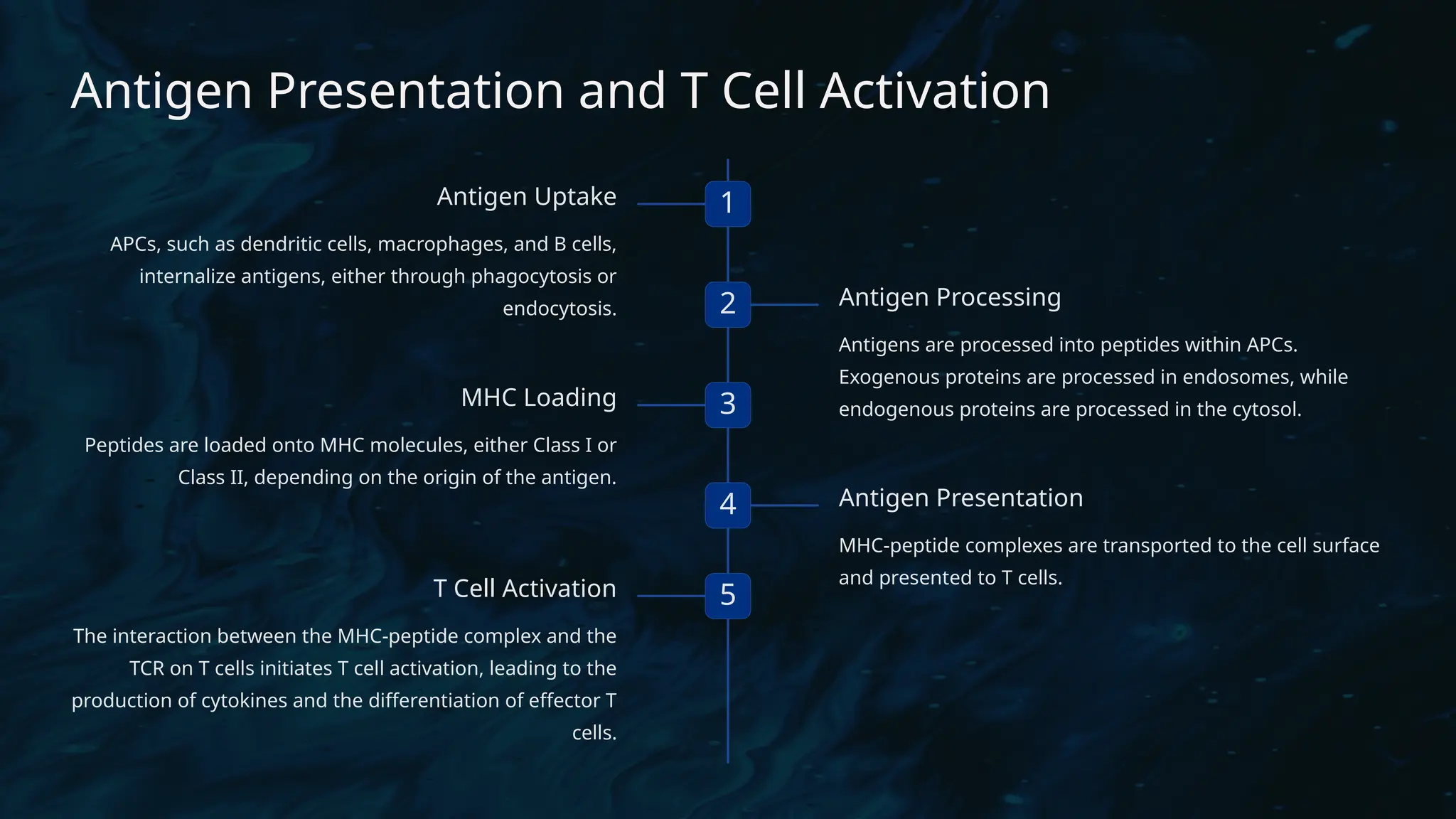

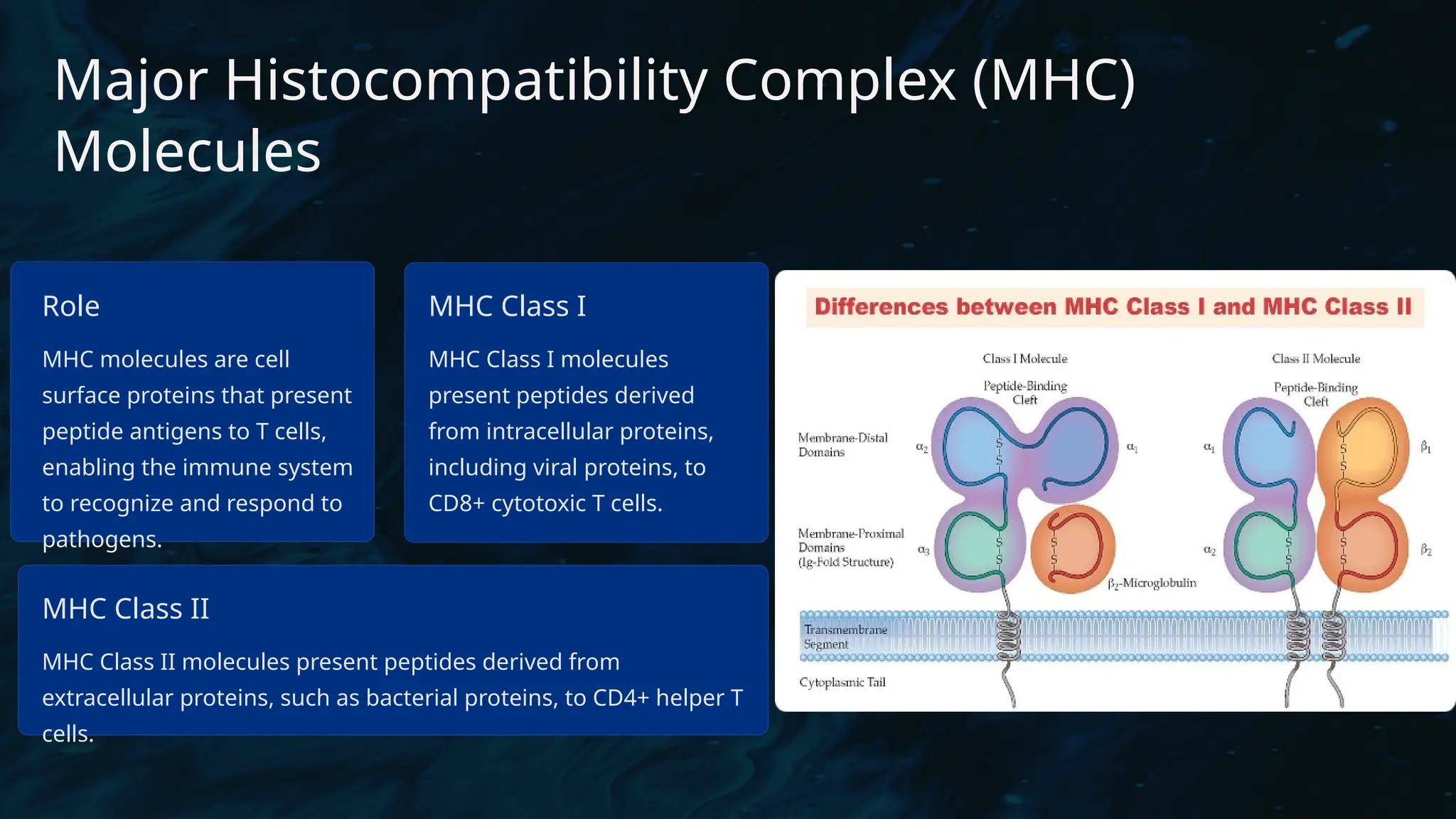

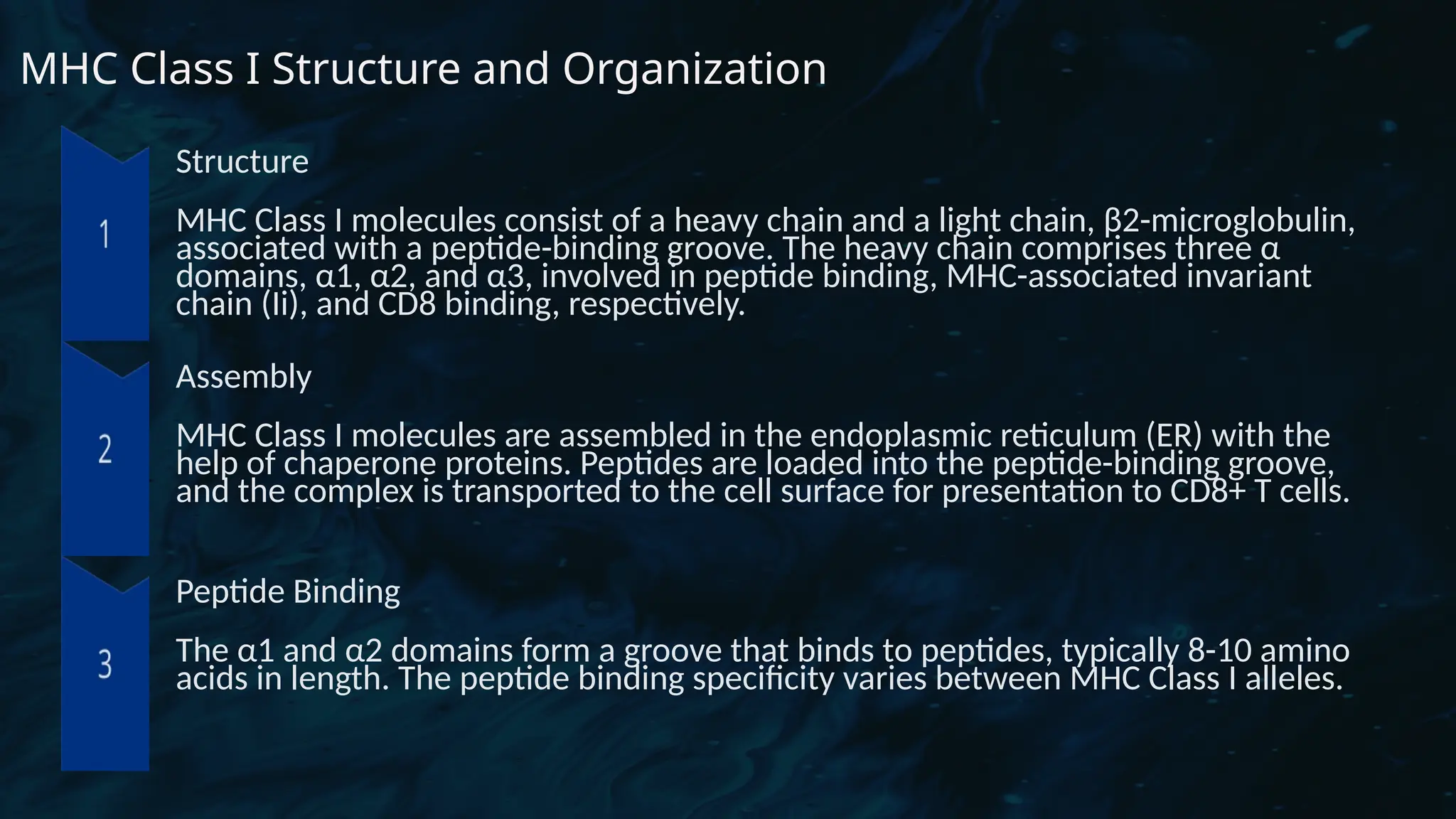

The document details the structure and function of B cell and T cell receptors (BCRs and TCRs), highlighting their roles in the adaptive immune system. BCRs are membrane-bound antibodies enabling antigen recognition and activation of B cells, while TCRs recognize peptide fragments presented by MHC molecules on antigen-presenting cells, leading to T cell activation. Furthermore, it emphasizes the significance of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) polymorphism in enhancing immune diversity and the challenges it poses in organ transplantation and autoimmune diseases.