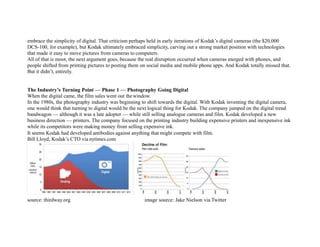

Kodak was once a dominant player in photography but failed to adapt to digital photography and the rise of smartphones. It invented the first digital camera in 1975 but did not embrace digital photography as the future. Kodak focused on printing photos from film rather than the digital cameras and online photo sharing that became popular. By the time Kodak tried to transition to digital, it was too late, and the company filed for bankruptcy in 2012 as digital photography and photo sharing on social media surpassed film. Kodak's failure to reinvent itself for the digital age and its complacency ultimately led to its demise despite inventing key early digital photography technologies.