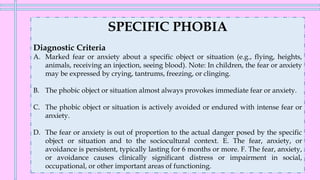

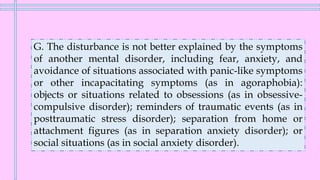

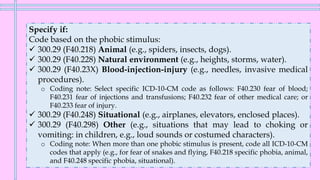

This document provides information on specific phobia, including the diagnostic criteria and specifiers. It notes that specific phobia involves a marked fear or anxiety about a specific object or situation. The fear is out of proportion to the actual threat and causes significant impairment. Common phobic stimuli include animals, heights, blood/injuries, and confined places. Individuals often experience physiological arousal when exposed to the feared object/situation.

![Features

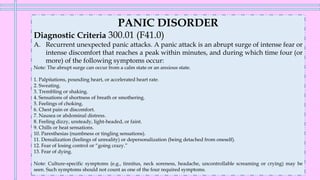

❖Attacks that meet all other criteria but have fewer than four physical

and/or cognitive symptoms are referred to as limited-symptom attacks.

❖There are two characteristic types of panic attacks: expected and

unexpected.

o Expected panic attacks are attacks for which there is an obvious cue

or trigger, such as situations in which panic attacks have typically

occurred.

o Unexpected panic attacks are those for which there is no obvious cue

or trigger at the time of occurrence (e.g., when relaxing or out of sleep

[nocturnal panic attack].

o Cultural interpretations may influence their determination as expected or

unexpected.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anxiety-disorders-230122212552-eae44e0a/85/ANXIETY-DISORDERS-pdf-59-320.jpg)

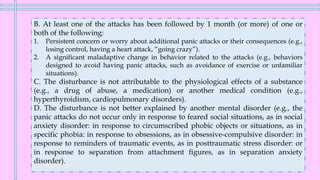

![Risk and Prognostic Factors

❖ Temperamental.

o Behavioral inhibition and neurotic disposition (i.e., negative affectivity

[neuroticism] and anxiety sensitivity) are closely associated with agoraphobia but

are relevant to most anxiety disorders (phobic disorders, panic disorder,

generalized anxiety disorder). Anxiety sensitivity (the disposition to believe that

symptoms of anxiety are harmful) is also characteristic of individuals with

agoraphobia.

❖ Environmental.

o Negative events in childhood (e.g., separation, death of parent) and other stressful

events, such as being attacked or mugged, are associated with the onset of

agoraphobia. Furthermore, individuals with agoraphobia describe the family

climate and child-rearing behavior as being characterized by reduced warmth and

increased overprotection.

❖ Genetic and physiological.

o Heritability for agoraphobia is 61%. Of the various phobias, agoraphobia has the

strongest and most specific association with the genetic factor that represents

proneness to phobias.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anxiety-disorders-230122212552-eae44e0a/85/ANXIETY-DISORDERS-pdf-66-320.jpg)

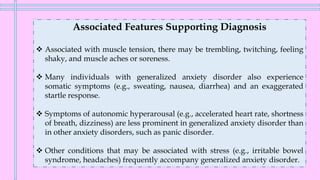

![GENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER

Diagnostic Criteria 300.02 (F41.1)

E. The disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a

drug of abuse, a medication) or another medical condition (e.g., hyperthyroidism).

F. The disturbance is not better explained by another mental disorder (e.g., anxiety or worry about

having panic attacks in panic disorder, negative evaluation in social anxiety disorder [social phobia],

contamination or other obsessions in obsessive-compulsive disorder, separation from attachment

figures in separation anxiety disorder, reminders of traumatic events in posttraumatic stress disorder,

gaining weight in anorexia nervosa, physical complaints in somatic symptom disorder, perceived

appearance flaws in body dysmorphic disorder, having a serious illness in illness anxiety disorder, or

the content of delusional beliefs in schizophrenia or delusional disorder).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anxiety-disorders-230122212552-eae44e0a/85/ANXIETY-DISORDERS-pdf-70-320.jpg)

![ANXIETY DISORDER DUE TO ANOTHER MEDICAL

CONDITION

Diagnostic Criteria 293.84 (F06.4)

A. Panic attacks or anxiety is predominant in the clinical picture.

B. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance

is the direct pathophysiological consequence of another medical condition.

C. The disturbance is not better explained by another mental disorder.

D. The disturbance does not occur exclusively during the course of a delirium.

E. The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other

important areas of functioning.

Coding note: Include the name of the other medical condition within the name of the mental disorder (e.g., 293.84

[F06.4] anxiety disorder due to pheochromocytoma). The other medical condition should be coded and listed

separately immediately before the anxiety disorder due to the medical condition (e.g., 227.0 [D35.00]

pheochromocytoma; 293.84 [F06.4] anxiety disorder due to pheochromocytoma.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anxiety-disorders-230122212552-eae44e0a/85/ANXIETY-DISORDERS-pdf-80-320.jpg)

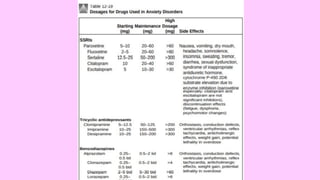

![TREATMENT

A. Pharmacologic.

3. Tricyclics (imipramine, nortryptaline, clomipramine)

✓ Drugs in this class reduce the intensity of anxiety in all the anxiety disorders.

✓ SE: anticholinergic effects, cardiotoxicity, and potential lethality in overdose [10 times the daily

recommended dose can be fatal] → they are not first-line agents!

4. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (phenelzine, tranylcypromine)

✓ MAOIs are effective for the treatment of panic and other anxiety disorders

✓ SE: occurrence of a hypertensive crisis (tramine) → not first-line agents!

✓ Certain medications such as sympathomimetics and opioids (especially meperidine [Demerol])

must be avoided because if combined with MAOIs, death may ensue!

5. Other drugs used in anxiety disorders

a. Adrenergic receptor antagonists (beta blockers)

b. Venlafaxine

c. Buspirone

d. Anticonvulsants anxiolytics](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anxiety-disorders-230122212552-eae44e0a/85/ANXIETY-DISORDERS-pdf-88-320.jpg)