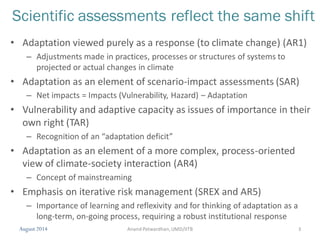

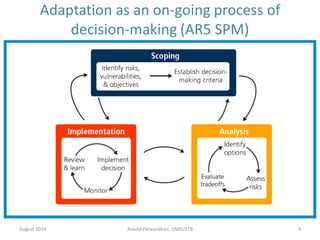

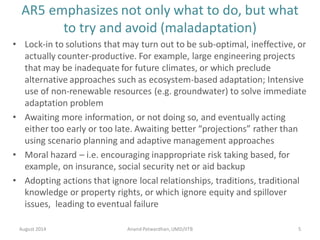

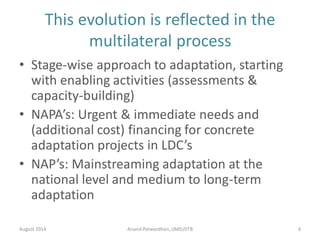

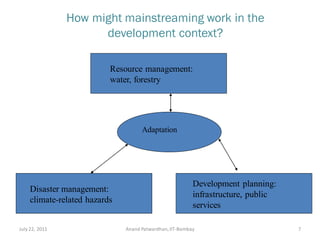

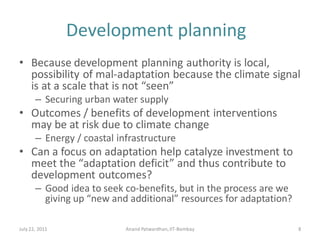

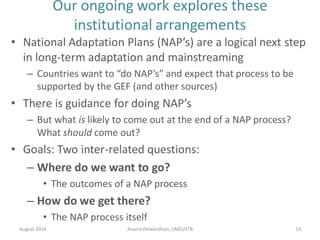

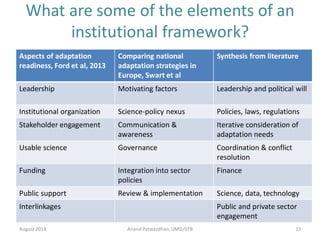

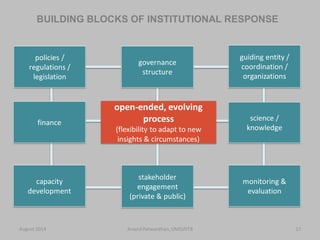

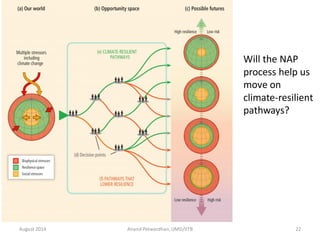

The document discusses the evolution of adaptation within development contexts, emphasizing the need for mainstreaming adaptation into long-term development strategies. It highlights the shift from viewing adaptation merely as a response to climate change to considering it an integral part of decision-making processes across various sectors. The document also outlines institutional arrangements and governance challenges necessary for effective adaptation planning and implementation.