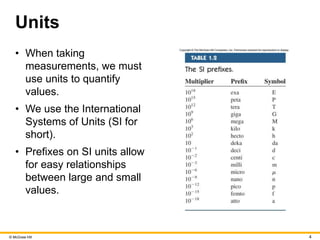

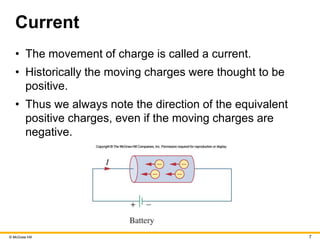

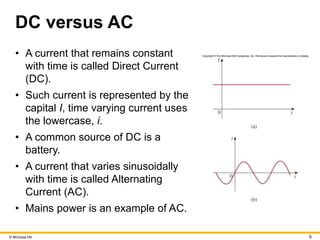

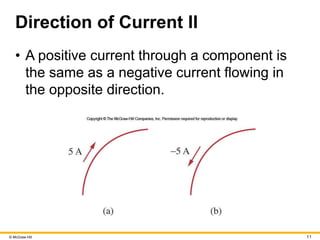

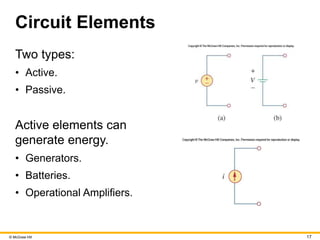

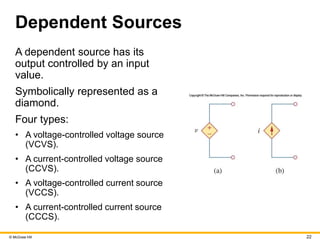

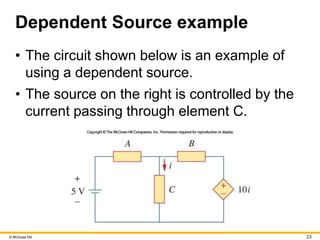

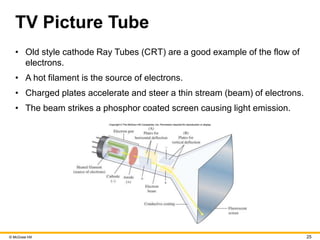

This document introduces key concepts in electric circuits including voltage, current, circuit elements, and problem solving strategies. It defines voltage and current, and introduces the concepts of direct current, alternating current, and their units. It describes circuit elements like sources, resistors, capacitors and inductors. It also outlines a six step process for solving circuit problems which includes defining the problem, presenting known information, considering alternative solutions, attempting a solution, evaluating the solution, and determining if it is satisfactory.