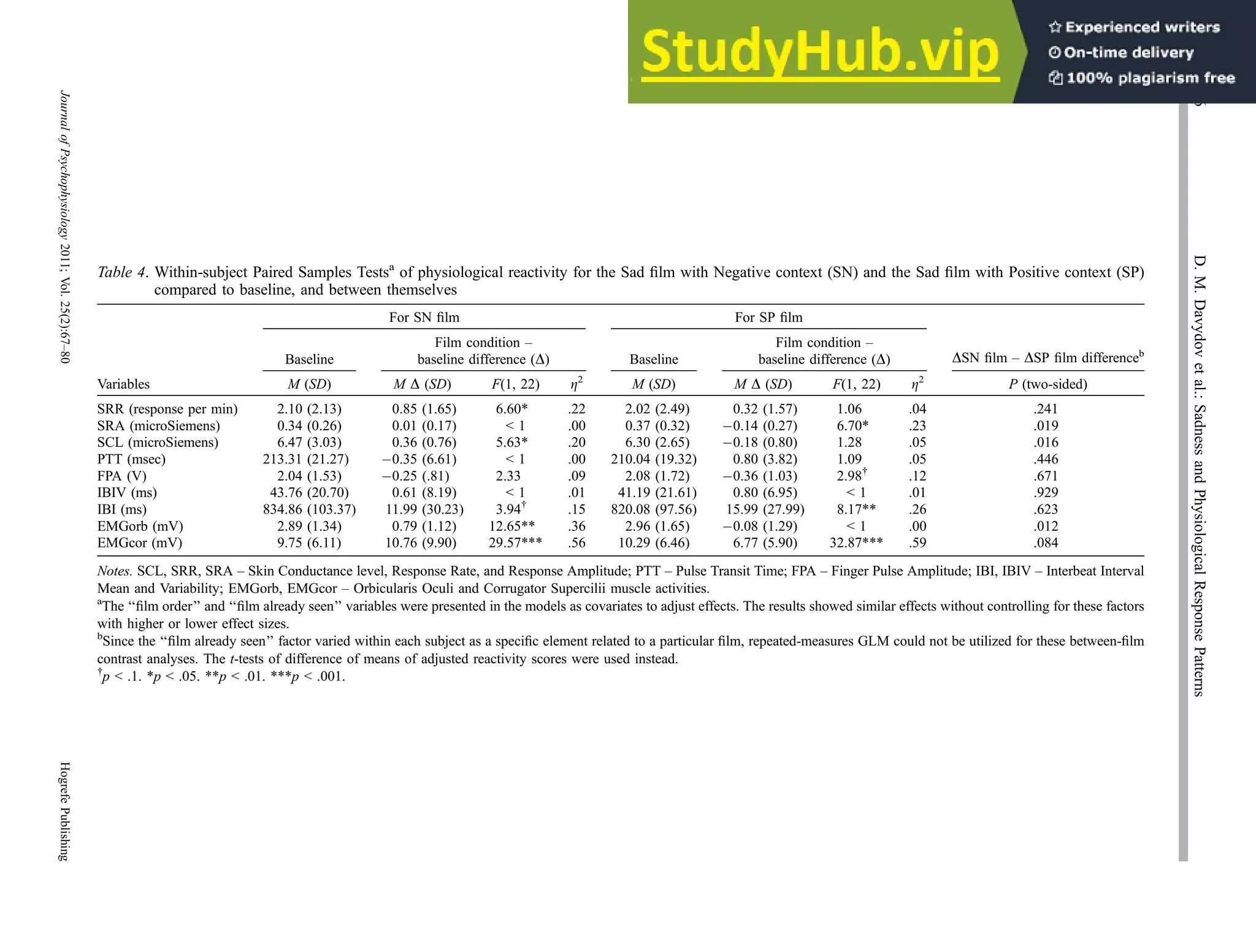

This study tested how different emotional contexts influence physiological responses to sadness. Participants watched two sad films, one with an additional context of disgust (related to avoidance) and one with tenderness (related to attachment). Both films increased facial expressions of sadness but had opposite effects physiologically. The sad+disgust film increased skin conductance, while the sad+tenderness film decreased heart rate and skin conductance responses, showing emotional contexts can alter arousal levels in response to the same emotion.

![(Gračanin, Kardum, Hudek-Knežević, 2007; Kreibig et

al., 2007; Van Gucht et al., 2008) and provide data on

self-reported emotional intensity scores, positive and nega-

tive affect levels (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988), 16 discrete

emotional ratings (Schaefer et al., 2003), and discreteness of

the emotion scores for these film clips (see Table 1). Dis-

crete emotional ratings are assessments of the intensity of

particular feelings related to the 16 differential emotions

scales. Discreteness of emotional states is the degree to

which one emotional state is uniquely activated while other

possible emotions are less activated: the mean score of the

scale targeting one particular emotion (from the discrete

emotional ratings) minus the averaged mean scores of the

scales targeting the other emotions. For example, a higher

score on a sadness self-report item while other items like

anger or happiness yield lower scores suggests that a state

of sadness has been activated with higher degree of discrete-

ness. Level of emotional intensity of a film clip is related to

how efficient the stimulus is in determining not a particular

emotion or an emotional dimension, but the global emo-

tional state (from no emotion to very intense emotion).

The clips were also evaluated on the PANAS global positive

and negative affect subscales. Three clips ‘‘Sadness with

Negative context’’ (SN) and seven clips ‘‘Sadness with Posi-

tive context’’ (SP) were first picked according to the global

affect indicated by the PANAS (positive affect – negative

affect). Then, the selected SN and SP clips were balanced

on length, rating, discreteness of the common emotion (sad-

ness), and global emotional intensity. The clips were also

appraised for contrasts in ratings and discreteness of addi-

tional emotions (disgust and tenderness). Two short clips

known to elicit sadness plus an additional emotion (either

negative – disgust, or positive – tenderness), high global

emotional intensity, and interest were used in this study.

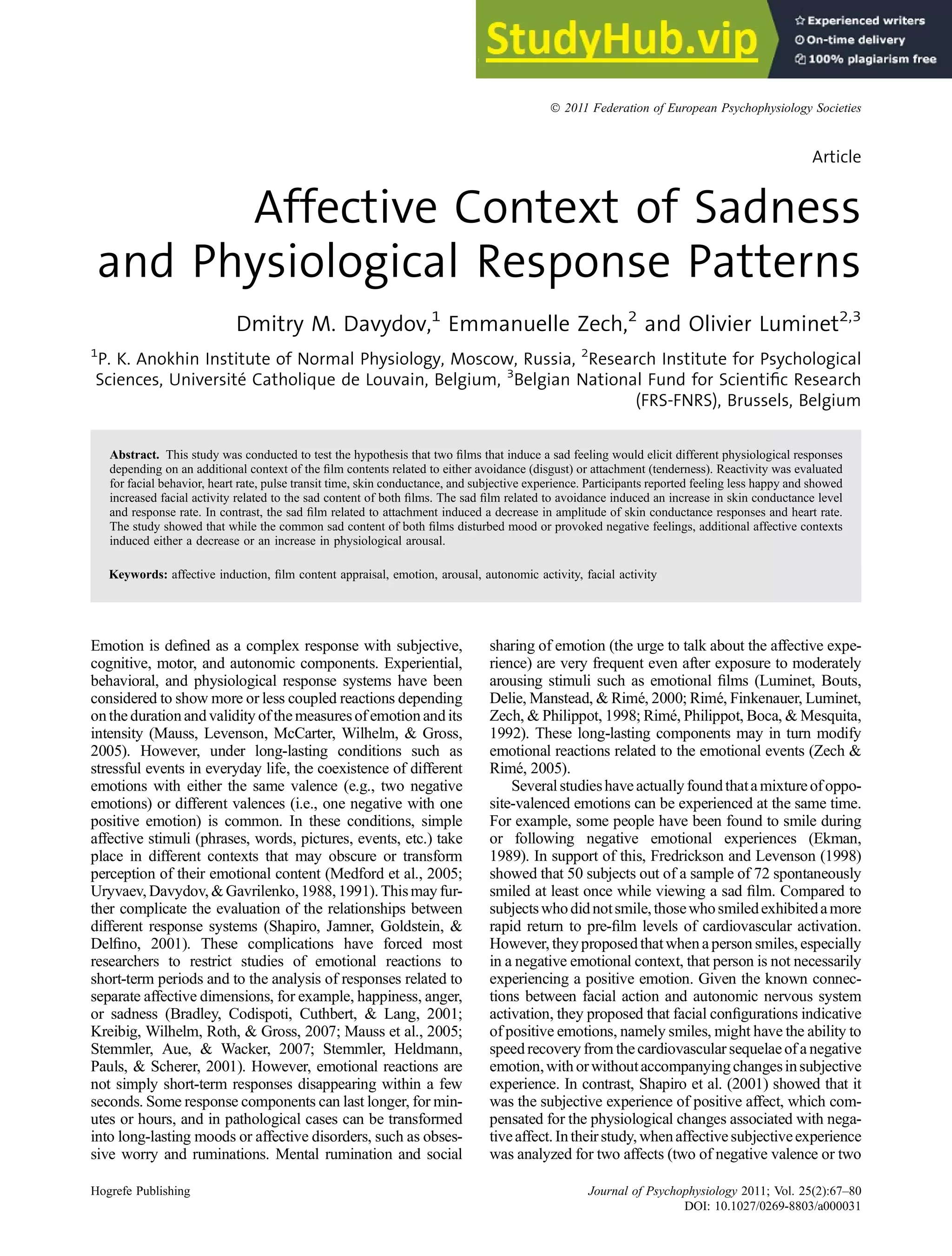

Table 1. Attributes of two sad film clips with different additional ‘‘Positive’’ (SP) or ‘‘Negative’’ (SN) emotional contexts

(from Schaefer et al., 2008)

Sad film with ‘‘Positive’’

(‘‘attachment’’) context (SP)

Sad film with ‘‘Negative’’

(‘‘avoidance’’) context (SN)

Variable ‘‘Philadelphia’’ ‘‘Dead man walking’’

Time 50

2800

60

4000

Global emotional intensity rating score 5.24 5.87

General affect (positive – negative

affects measured with PANAS)

0.47 (1.94–1.47) 0.63 (1.99–2.31)

A priori emotional category of the film excerpt Sadness Sadness

SADness rating score 4.37 4.21

Discreteness of SADness (score) 2.27 1.02

Additional strong emotion (rating score) Tenderness (4.35) Disgust (5.30)

Discreteness of additional emotion (score) 2.25 2.33

Ratings of feeling (7-point scales):

Interested 5.81 5.91

Fearful 1.94 3.46

Anxious 2.31 4.64

Moved 4.35 2.23

Angry 1.57 3.96

Ashamed 1.28 1.84

Warmhearted 1.33 1.14

Joyful 1.22 1.02

Sad 4.37 4.21

Satisfied 1.35 1.29

Surprised 1.48 2.18

Loving 1.89 1.27

Guilty 1.50 1.70

Disgusted 1.41 5.30

Disdainful 1.07 3.20

Calm 3.93 2.36

Discreteness (highest [7] to lowest [ 7]) of

Joy 1.51 2.82

Tenderness 2.25 1.36

Anger 1.09 0.72

Sadness 2.27 1.02

Fear 0.64 0.12

Disgust 1.29 2.33

70 D. M. Davydov et al.: Sadness and Physiological Response Patterns

Journal of Psychophysiology 2011; Vol. 25(2):67–80 Hogrefe Publishing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/affectivecontextofsadnessandphysiologicalresponsepatterns-230804170455-24695d0f/75/Affective-Context-Of-Sadness-And-Physiological-Response-Patterns-4-2048.jpg)

![Gold, P. W., Chrousos, G. P. (2002). Organization of the stress

system and its dysregulation in melancholic and atypical

depression: high vs low CRH/NE states. Molecular Psychi-

atry, 7, 254–275.

Gračanin, A., Kardum, I., Hudek-Knežević, J. (2007).

Relations between dispositional expressivity and physiolog-

ical changes during acute positive and negative affect.

Psychological Topics, 16, 311–328.

Koelsch, S., Remppis, A., Sammler, D., Jentschke, S., Mietchen,

D., Fritz, T., Bonnemeier, H., Siebel, W. A. (2007). A

cardiac signature of emotionality. The European Journal of

Neuroscience, 26, 3328–3338.

Kreibig, S. D., Wilhelm, F. H., Roth, W. T., Gross, J. J. (2007).

Cardiovascular, electrodermal, and respiratory response pat-

terns to fear- and sadness-inducing films. Psychophysiology,

44, 787–806.

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., Cuthbert, B. N. (1997). International

Affective Picture System(IAPS): Technical Manualand Affective

Ratings. Gainesville, FL: NIMH Center for the Study of

Emotion and Attention, University of Florida.

Lovell, D. (Producer) (1979). Zeffirelli, F. (Director) (1979). The

Champ [Film]. Culver City, CA: MGM/UA.

Luminet, O., Bouts, P., Delie, F., Manstead, A. S. R., Rimé, B.

(2000). Social sharing of emotion following exposure to a

negatively valenced situation. Cognition Emotion, 14,

661–688.

Mauss,I.B.,Levenson,R.W.,McCarter,L.,Wilhelm,F.H.,Gross,

J. J. (2005). The tie that binds? Coherence among emotion

experience, behavior, and physiology. Emotion, 5, 175–190.

Medford, N., Phillips, M. L., Brierley, B., Brammer, M.,

Bullmore, E. T., David, A. S. (2005). Emotional memory:

Separating content and context. Psychiatry Research: Neu-

roimaging, 138, 247–258.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their

effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of

Abnormal Psychology, 100, 569–582.

Ortony, A., Turner, T. J. (1990). What’s basic about basic

emotions? Psychological Review, 97, 315–331.

Ottaviani, C., Shapiro, D., Davydov, D. M., Goldstein, I. B.

(2008). Autonomic stress response modes and ambulatory

heart rate level and variability. Journal of Psychophysiology,

22, 28–40.

Pollak, M. H., Obrist, P. A. (1983). Aortic-radial pulse transit

time and ECG Q-wave to radial pulse wave interval as

indices of beat-by-beat blood pressure change. Psychophys-

iology, 20, 21–28.

Rimé, B., Finkenauer, C., Luminet, O., Zech, E., Philippot, P.

(1998). Social sharing of emotion: New evidence and new

questions. In W. Stroebe, M. Hewstone (Eds.), European

Review of Social Psychology (Vol. 9, pp. 145–189).

Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Rimé, B., Philippot, P., Boca, S., Mesquita, B. (1992). Long-

lasting cognitive and social consequences of emotion: Social

sharing and rumination. In W. Stroebe, M. Hewstone

(Eds.), European Review of Social Psychology (Vol. 3, pp.

225–258). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Roberts, N. A., Levenson, R. W., Gross, J. J. (2008).

Cardiovascular costs of emotion suppression cross ethnic

lines. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 70, 82–87.

Rohrmann, S., Hopp, H. (2008). Cardiovascular indicators of

disgust. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 68, 201–

208.

Rozin, P. (1999). Preadaptation and the puzzles and properties of

pleasure. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, N. Schwarz (Eds.),

Well being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 109–

133). New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Schaefer, A., Collette, F., Philippot, P., Vanderlinden, M.,

Laureys, S., Delfiore, G., . . . Salmon, E. (2003). Neural

correlates of ‘‘hot’’ and ‘‘cold’’ emotional processing: A

multilevel approach to the functional anatomy of emotions.

Neuroimage, 18, 938–949.

Schaefer, A., Nils, F., Sanchez, X., Philippot, P. (2008).

Assessing the effectiveness of a large database of emotion-

eliciting films: A new tool for emotion researchers. Technical

report, University of Louvain, 10 Place du Cardinal Mercier,

1348-Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium.

Scherer, K. R., Schorr, A., Johnstone, T. (2001). Appraisal

processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research. New York,

NY: Oxford University Press.

Shapiro, D., Jamner, L. D., Goldstein, I. B., Delfino, R. J.

(2001). Striking a chord: Moods, blood pressure, and heart

rate in everyday life. Psychophysiology, 38, 197–204.

Stark, R., Stone, A., White, V. (Producers), Ross, H. (Director)

(1989). Steel Magnolias [Film]. TriStar Pictures.

Stemmler, G., Aue, T., Wacker, J. (2007). Anger and fear:

Separable effects of emotion and motivational direction on

somatovisceral responses. International Journal of Psycho-

physiology, 66, 141–153.

Stemmler, G., Heldmann, M., Pauls, C. A., Scherer, T. (2001).

Constraints for emotion specificity in fear and anger: The

context counts. Psychophysiology, 38, 275–291.

Uryvaev, Iu. V., Davydov, D. M., Gavrilenko, A. Ia. (1988).

An improved method of speech audiometry. Vestnik Otori-

nolaringologii [Bulletin of Otolaryngology], 3, 34–39.

Uryvaev, Iu. V., Davydov, D. M., Gavrilenko, A. Ia. (1991).

Study of food dominants by means of a verbal test.

Fiziologiia Cheloveka [Human Physiology], 17, 67–72.

Van der Does, W. (2002). Different types of experimentally

induced sad mood? Behavior Therapy, 33, 551–561.

Van Gucht, D., Vansteenwegen, D., Beckers, T., Hermans, D.,

Baeyens, F., Van den Bergh, O. (2008). Repeated cue

exposure effects on subjective and physiological indices of

chocolate craving. Appetite, 50, 19–24.

Volokhov, R. N., Demaree, H. A. (2010). Spontaneous

emotion regulation to positive and negative stimuli. Brain

and Cognition, 73, 1–6.

Wallbott, H. G., Scherer, K. R. (1986). How universal and

specific is emotional experience? Evidence from 27 countries

on five continents. Social Science Information, 25, 763–795.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., Tellegen, A. (1988). Development

and validation of brief measures of positive and negative

affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 54, 1063–1070.

Zech, E., Rimé, B. (2005). Is talking about an emotional

experience helpful? Effects on emotional recovery and

perceived benefits. Clinical Psychology Psychotherapy,

12, 270–287.

Accepted for publication: June 15, 2010

Dmitry M. Davydov

P. K. Anokhin Institute of Normal Physiology

11-4 Mokhovaya ulitsa

Moscow, 125009

Russia

Tel. +7 495 496-5234

E-mail d.m.davydov@gmail.com

80 D. M. Davydov et al.: Sadness and Physiological Response Patterns

Journal of Psychophysiology 2011; Vol. 25(2):67–80 Hogrefe Publishing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/affectivecontextofsadnessandphysiologicalresponsepatterns-230804170455-24695d0f/75/Affective-Context-Of-Sadness-And-Physiological-Response-Patterns-14-2048.jpg)