This document provides information about open esophageal surgical procedures, including cricopharyngeal myotomy and excision of Zenker's diverticulum. It describes the preoperative evaluation and optimization of patients, including imaging, endoscopy, and nutritional support. The surgical technique is explained in 4 steps: 1) incision and dissection of the pharyngeal pouch, 2) myotomy of the cricopharyngeus muscle and esophagus, 3) freeing or excising the diverticulum using a stapler, and 4) drainage/closure. Postoperative care involves monitoring for complications such as recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, fistula, hematoma, and infection.

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 1

7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES

John Yee, M.D., F.R.C.S.C., and Richard J. Finley, M.D., F.A.C.S., F.R.C.S.C.

The remarkable developments in diagnosis, imaging, and surgical nuclear studies for assessment of esophageal and gastric transit

treatment of esophageal diseases over the past 15 years have result- provide functional data that can facilitate the diagnosis and treat-

ed in markedly better patient outcomes: the morbidity and mor- ment of GERD, achalasia, and other disorders of the esophagus.

tality associated with surgery of the esophagus have been substan- They are useful complements to standard investigations (e.g., ciné

tially reduced. In particular, the operative techniques employed to barium swallow and endoscopy).

treat esophageal disease have advanced considerably, as a result of Complete preoperative investigation of all patients, even those

an improved understanding of esophageal anatomy and physiolo- with classic histories and physical findings, is mandatory.The data

gy and the successful introduction of minimally invasive approach- from anatomic and functional testing allow the surgeon to plan the

es to the esophagus [see 4:8 Minimally Invasive Esophageal Procedures]. operation more appropriately and effectively (e.g., deciding on the

For a number of diseases (e.g., achalasia), minimally invasive pro- need for esophageal lengthening in patients with paraesophageal

cedures have proved to be as effective as their open counterparts hernias or choosing between a complete and a partial fundoplica-

while causing less postoperative morbidity.The growing stature of tion in patients with hernias associated with varying degrees of

minimally invasive approaches does not, however, diminish the im- esophageal dysmotility).

portance of the equivalent open approaches. In this chapter, we

OPTIMIZATION OF PATIENT HEALTH STATUS

describe common open operations performed to excise Zenker’s

diverticulum, to manage complex gastroesophageal reflux disease Patients with obstructing esophageal diseases are often elderly,

(GERD), and to resect esophageal and proximal gastric tumors. debilitated, and malnourished. Although months of insufficient

nutrition cannot be corrected in the space of a few hours, anemia,

dehydration, and electrolyte abnormalities can be mitigated by

General Preoperative Considerations means of intravenous support and appropriate laboratory monitor-

ing. If esophageal obstruction prevents oral intake, endoscopic dila-

METHODS OF PATIENT ASSESSMENT

tion of the stricture, accompanied by either nasogastric intubation

The functional results achieved with esophageal procedures or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) [see 5:18 Gastro-

become more predictable when the approach to preoperative intestinal Endoscopy], is indicated; the patient should then be able to

patient evaluation is precise and reproducible. The ciné barium resume at least a liquid diet. If weight loss has exceeded 10%, enter-

swallow remains the most cost-effective method for initial evalua- al nutrition, comprising at least 2,000 kcal/day of a high-protein liq-

tion of esophageal anatomy and function. It should be employed uid diet, should be administered for at least 10 days before the oper-

before endoscopy because the results may direct the endoscopist’s ation. Cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, and respiratory function should

attention to particular areas of concern. For example, a finding of be documented and optimized. If the patient is aspirating, the esoph-

abnormal angulation or strictures indicates that the endoscopist agus should be evacuated and the patient should be given nothing

should either use a pediatric-caliber endoscope or exercise more by mouth until after the operation. Aspiration pneumonia should

caution in passing a standard adult endoscope. In addition, endo- always be corrected preoperatively.

scopic examination alone is often insufficient for assessing

esophageal motility disorders or defining the complex anatomy of

a paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Cricopharyngeal Myotomy and Excision of Zenker’s

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is an extension of the Diverticulum

visual mucosal examination. The information it can provide

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

about the extension of mass lesions beyond the confines of the

esophageal wall is helpful in planning surgical resection. In addi- Patients who are candidates for cricopharyngeal myotomy usu-

tion, EUS can differentiate benign stromal tumors from cystic or ally present with difficulty initiating swallowing, cervical dysphagia

malignant neoplasms on the basis of characteristic echogenicity or odynophagia [see 4:1 Dysphagia], and a history of pulmonary

patterns. The combination of EUS and computed tomography aspiration. These symptoms of cricopharyngeal dysfunction may

permits highly precise anatomic assessment of esophageal neo- or may not be associated with a Zenker’s diverticulum. Ciné con-

plasms, definition of the extent of local invasion, and identifica- trast studies may reveal poor pharyngeal contractility, pulmonary

tion of regional metastases. or nasal aspiration, abnormalities of the upper esophageal sphinc-

Functional imaging with photodynamic or vital staining allows ter, pharyngeal pouches, or other structural abnormalities in the

accurate diagnosis of dysplastic or malignant mucosal lesions in distal esophagus. Barium is the usual contrast agent, but if aspira-

their earliest stages. Positron emission tomography (PET) yields tion is suspected, a nonionic contrast agent can be used instead to

similar results by localizing metabolically active tissue regionally or prevent pneumonitis.

at distant sites. The combination of morphologic data from high- Zenker’s diverticulum is a pulsion diverticulum that arises

resolution CT and functional data from PET is particularly effec- adjacent to the inferior pharyngeal constrictor, between the

tive for identifying occult metastases that would preclude curative oblique fibers of the posterior pharyngeal constrictors and the

resection for esophageal cancer. cricopharyngeus muscle. This mucosal outpouching results from

Esophageal manometry, 24-hour esophageal pH testing, and a transient incomplete opening of the upper esophageal sphinc-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acs0407-openesophagealprocedures-100726063211-phpapp02/85/Acs0407-Open-Esophageal-Procedures-1-320.jpg)

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 2

roll is placed behind the shoulders to extend the neck.The patient

is placed in a 20º reverse Trendelenburg position, and the legs are

wrapped with pneumatic calf compressors to prevent deep vein

thrombosis (DVT).With the endotracheal tube placed to the left

side of the mouth, a preliminary flexible esophagogastroscopy is

performed to empty the diverticulum of all food and to examine

the esophagus and the stomach. The scope is then brought back

up into the oropharynx and moved into the pouch. The location

of the diverticulum (on the left or the right side) is confirmed by

turning off the room lights and noting which side is transillumi-

nated by the gastroscope.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

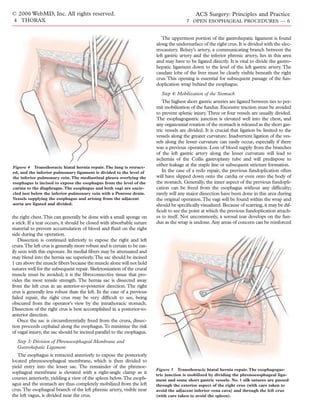

Step 1: Incision and Dissection of Pharyngeal Pouch

The patient lies with the head turned away from the side on

which the incision is made. The cricoid cartilage is palpated and

marked. A 4 cm skin incision is made, either obliquely along the

sternocleidomastoid muscle [see Figure 1] or transversely in a skin

crease at the level of the cricoid. The platysma is divided in the

same line. Self-retaining retractors are inserted. The anterior bor-

der of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is incised throughout its

length.The omohyoid muscle and the sternohyoid and sternothy-

roid muscles are retracted [see Figure 2]. The sternocleidomastoid

muscle is retracted laterally to expose the carotid sheath and the

Figure 1 Cricopharyngeal myotomy and excision of Zenker’s internal jugular vein.The middle thyroid vein is ligated and divid-

diverticulum. A soft roll is placed behind the shoulders to extend ed, and the thyroid gland and the trachea are retracted medially by

the neck. The head is turned to the side opposite the incision. The

the assistant’s finger to minimize the risk of injury to the underly-

cricoid cartilage is palpated and marked. The skin is incised

obliquely along the sternocleidomastoid muscle, as shown, or

ing recurrent laryngeal nerve. There is no need to encircle the

transversely in a skin crease at the level of the cricoid. esophagus or to dissect in the tracheoesophageal groove.The deep

cervical fascia is divided. The inferior thyroid artery is divided as

laterally as possible. The carotid sheath is retracted laterally, and

ter. The diverticulum ultimately enlarges, drapes over the crico-

pharyngeus, and dissects behind the esophagus into the prever-

tebral space.The pouch usually deviates to one side or the other;

Thyroid Gland

accordingly, the side on which the deviation occurs must be

determined by means of a barium swallow so that the appropri- Omohyoid Muscle

ate operative approach can be selected. Esophageal motility stud-

ies may show either incomplete upper esophageal relaxation on

swallowing or poor coordination of the upper esophageal relax-

ation phase with pharyngeal contractions. Upper GI endoscopy

is performed preoperatively to exclude the presence of a pharyn-

geal or esophageal carcinoma and to assess the upper GI anato-

my. If there is evidence of GERD, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

are given.

In symptomatic patients (e.g., those with dysphagia, nocturnal

cough, or recurrent pneumonia from aspiration), surgical therapy

is indicated regardless of whether a pouch is present or how large

it may be. Such treatment involves correcting the underlying cri- Inferior

copharyngeal muscle dysfunction with a cricopharyngeal myoto- Thyroid

my. If there is a diverticulum larger than 2 cm, it should be excised Artery

in addition to the cricopharyngeal myotomy. Alternatively, the

diverticulum may be managed via endoscopic obliteration of the

common wall between the pharyngeal pouch and the esophagus

with either a stapler or a laser. Cricopharyngeal incoordination

may be temporarily relieved by injecting botulinum toxin into the

cricopharyngeus.

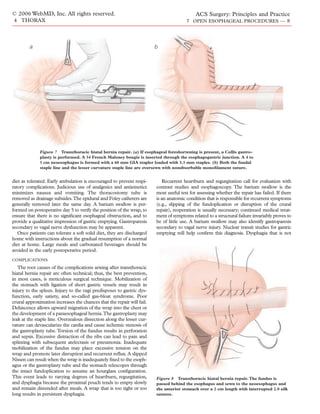

Figure 2 Cricopharyngeal myotomy and excision of Zenker’s

OPERATIVE PLANNING diverticulum. The sternocleidomastoid is incised along the ante-

rior border so as to expose the omohyoid muscle and the ster-

The patient is placed on a clear fluid diet for 2 days before the nohyoid and sternothyroid muscles, which are retracted. The thy-

operation. With the patient under general anesthesia, the trachea roid gland and the trachea are retracted medially by the assis-

is intubated with a single-lumen endotracheal tube. Cricoid pres- tant’s finger, and the inferior thyroid artery is ligated and divided

sure is applied to prevent aspiration of diverticular contents. A soft laterally to avoid injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acs0407-openesophagealprocedures-100726063211-phpapp02/85/Acs0407-Open-Esophageal-Procedures-2-320.jpg)

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 3

a b

Left

Recurrent

Laryngeal

Nerve

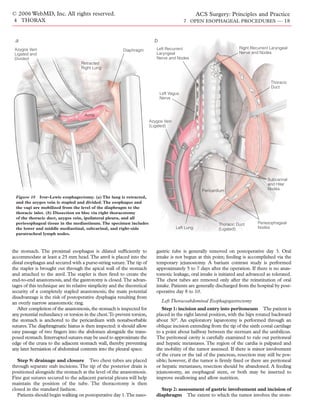

Figure 3 Cricopharyngeal myotomy and excision of Zenker’s diverticulum. (a) The diverticulum is dis-

sected away from the esophagus, and an esophageal myotomy is started approximately 3 cm below the

cricopharyngeus. The myotomy is continued proximally through the cricopharyngeus, and the muscle

around the diverticulum is freed. (b) A linear stapler is placed at the base of the sac and pressed firmly

against the esophagoscope. The stapler is fired, and the diverticulum is excised.

dissection is carried down to the prevertebral fascia [see Figure 2]. to injure the recurrent laryngeal nerve.The stapler is fired, and the

The endoscope placed in the diverticulum is palpated, and the diverticulum is excised.The staple line is cleaned with an antisep-

pouch is dissected away from the cervical esophagus up as far as the tic solution, and the incision is filled with saline.The esophagus is

pharyngoesophageal junction. The flexible endoscope is then insufflated with air to determine whether mucosal leakage has

removed from the pouch and advanced into the thoracic esopha- occurred, and the esophagoscope is removed; any mucosal leaks

gus so that it can be used as a stent for the cricopharyngeal myoto- found are closed with fine absorbable sutures. In the absence of a

my. Dissection of the pharyngeal pouch is then completed. stapler, the best way of excising the sac is to make a series of short

incisions through the neck of the sac with scissors, suturing the

Step 2: Myotomy edges after each cut with absorbable monofilament sutures (the

The esophageal myotomy is started approximately 3 cm below so-called cut-and-sew technique). The esophagoscope ensures

the cricopharyngeus on the posterolateral esophageal wall [see that the esophageal lumen is not narrowed.

Figure 3a].The esophageal muscle is divided down to the mucosa,

which is recognizable from its bluish coloration with the submu- Step 4: Drainage and Closure

cosal plexus overlying it.The esophageal muscle is dissected away Once hemostasis has been achieved, a short vacuum drain is

from the mucosa with a right-angle dissector and divided with a placed through the skin into the retroesophageal space.The platys-

low-intensity diathermy unit. The myotomy is then continued ma is repaired with absorbable sutures, and the skin is closed with

proximally through the cricopharyngeus and up into the muscular a subcuticular absorbable suture. Nasogastric intubation is unnec-

wall of the hypopharynx for 2 cm if there is no diverticulum pres- essary. Prokinetic agents and PPIs are administered to prevent

ent. The hypopharynx is distinguished by a pronounced submu- gastroesophageal reflux. A water-soluble contrast study is done on

cosal venous plexus. The muscle is then swept off the mucosa for the day of the operation. If the results are normal, the patient is

120°. started on a liquid diet, and the drain is removed on postoperative

day 1, when the patient is discharged.

Step 3: Freeing or Excision of Diverticulum

COMPLICATIONS

If there is a diverticulum less than 2 cm in diameter, the

cricopharyngeus is transected and the muscularis around the The main complications associated with cricopharyngeal myo-

diverticulum is freed. The myotomy is extended onto the tomy are recurrent laryngeal nerve trauma (occurring in 0.5% of

hypopharynx for 2 cm.The diverticulum may be suspended to the cases), fistulas (1%), hematoma formation, infection (2%), aspiration,

back wall of the pharynx. It should not be sutured to the prever- and recurrence (4%). Hematomas and infections must be drained

tebral fascia, because the passage of sutures through the divertic- promptly. Fistulas usually close once the prevertebral space is drained

ulum can contaminate the fascia, leading to an increased risk of and the associated infection controlled. Aspiration is the most

fascial infection. serious complication after cricopharyngeal myotomy. Gastroesoph-

If the diverticulum is more than 2 cm in diameter, it is excised ageal reflux may contribute to oropharnygeal dysphagia. Division

with a linear stapler loaded with 2.5 mm staples, which is placed of the upper esophageal sphincter in a patient with an incompetent

at the base of the sac and pressed firmly against the esophagoscope esophagogastric junction may lead to massive tracheobronchial

[see Figure 3b]. Particular care must be taken at this point so as not aspiration. Therefore, documented gastroesophageal reflux, gas-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acs0407-openesophagealprocedures-100726063211-phpapp02/85/Acs0407-Open-Esophageal-Procedures-3-320.jpg)

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 4

troesophageal regurgitation, and severe distal esophagitis may be the most appropriate form of repair is. Specifically, a history of

relative contraindications to cricopharyngeal myotomy until the heartburn and effortless regurgitation should be sought. Dysphagia

lower esophageal sphincter defect has been remedied with an anti- and odynophagia are not typically associated with hiatal hernia

reflux operation. unless there is a significant paraesophageal component. Persistent

dysphagia may reflect the presence of a stricture or a neoplasm [see

OUTCOME EVALUATION

4:1 Dysphagia]. Reflux-induced esophageal spasm may present

Of patients with a Zenker’s diverticulum, at least 90% experi- with occasional episodes of cervical dysphagia, but the transient

ence excellent results from surgical treatment. Of patients with- nature of the symptoms easily differentiates this condition from

out a Zenker’s diverticulum, one third experience excellent dysphagia caused by a fixed obstruction. Chest pain that radiates

results, another third show moderate improvement, and the remain- toward the back after meals and is relieved by nonbilious vomiting

ing third show no improvement.1 Patients with poor pharyngeal may indicate the presence of an incarcerated intrathoracic stomach

contractility in conjunction with normal upper esophageal that is hindering the emptying of the paraesophageal component.

sphincter function show little improvement with cricopharyngeal Atypical chest pain from cholelithiasis, peptic ulcer, or coronary

myotomy. Patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia secondary to artery disease may confound the diagnosis.

neurologic involvement who have intact voluntary deglutination,

adequate pulsion of the tongue, and normal phonation may Imaging

show improvement with cricopharyngeal myotomy. Appropriate Radiographic investigation should begin with a ciné barium

selection of patients for cricopharyngeal myotomy leads to bet- swallow, which will yield valuable information regarding the length

ter surgical outcomes. of the esophagus, its peristaltic function, and the integrity of the

mucosal surface. The gastric views can be used for qualitative

assessment of distal emptying. Any paraesophageal component

Transthoracic Hiatal Hernia Repair will be clearly demonstrated, along with any associated organoax-

Unlike most operations on the esophagus, which are extirpative ial volvulus. A simple barium swallow often yields the most useful

procedures, hiatal hernia repair with fundoplication is a recon- information for managing the complex problem of recurrent hiatal

structive procedure, the aim of which is to restore a high-pressure hernia and a slipped Nissen fundoplication.

zone at the esophagogastric junction that prevents reflux but also Next, esophagogastroscopy should be performed to examine

permits comfortable swallowing. Currently, this repair is often the mucosa for the presence of esophagitis, Barrett’s mucosa, stric-

accomplished via minimally invasive approaches; however, such ture, or malignancy. The locations of any lesions observed, along

approaches may be hampered by significant perceptual and motor with the position of the squamocolumnar junction, should be care-

limitations, such as loss of stereopsis, reduced tactile feedback, and fully documented in terms of their distance from the incisors. All

decreased range of motion for the instruments.The degree of ten- strictures must undergo cup or brush biopsy to rule out an occult

sion on the hiatal repair sutures, the quality of the crural tissue malignancy.The presence of severe esophagitis raises the possibil-

itself, and the caliber of the esophageal hiatus after repair all must ity of acquired shortening of the esophagus secondary to trans-

be assessed. In certain patients, laparoscopic reconstruction of a mural inflammation and contraction scarring. Every effort should

competent gastroesophageal high-pressure zone may be very diffi- be made to measure the length of the esophagus accurately.

cult and may demand a degree of tactile sensitivity that is not yet

achievable via video laparoscopy. Dilation

The long-term success of antireflux surgery, whether done via If a stricture is found during esophagoscopy, a decision must be

the transthoracic approach or by means of laparoscopy, depends made about whether to attempt esophageal dilation. This proce-

on three factors: (1) a tension-free repair that maintains a 4 cm dure carries the risk of perforation and should be performed only

long segment of esophagus in the intra-abdominal position, (2) after careful consideration. If the stricture is diagnosed at the time

durable approximation of the diaphragmatic crura, and (3) correct of the initial endoscopic examination, it is advisable to perform

matching of the fundoplication technique chosen to the peristaltic only the brush biopsy at this point, deferring dilation to a subse-

function of the esophagus. The transthoracic approach should be quent visit. Delaying dilation gives the surgeon time to reassess the

considered whenever the standard abdominal approaches to hiatal anatomy depicted on the barium swallow, to decide whether wire-

hernia repair carry an increased risk of failure or complication— guided dilation is necessitated by angulation of the esophagus, to

for example, in patients who have a foreshortened esophagus asso- obtain informed consent, to assemble the requisite equipment,

ciated with a massive hernia and an incarcerated intrathoracic and to plan sedation for what is often an uncomfortable proce-

stomach, patients with severe peptic strictures of the esophagus, dure. If a malignancy is suspected at the time of the initial endo-

patients in whom the hiatal hernia coexists with an esophageal scopic examination, dilation should be avoided. In this situation,

motility disorder or morbid obesity, and patients who have under- repair is impossible; thus, if iatrogenic perforation of a malignant

gone multiple previous abdominal operations. The transthoracic stricture occurs, the surgeon will have to attempt emergency resec-

repair is particularly useful when a previous open abdominal pro- tion in an inadequately prepared patient in whom proper staging

cedure has failed. In this situation, the reasons for such failure, is unlikely to have been completed.

whether technical or tissue-related, should be assessed so that a The standard flexible adult esophagoscope is approximately 32

compensatory strategy can be devised. French in caliber. In advancing the scope into the stricture, only

very gentle pressure should be necessary. As a rule, a mild stricture

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

that is not associated with steep angulation of the esophagus will

readily accept passage of the endoscope and will be amenable to

Symptomatic Evaluation subsequent blind dilation with Hurst-Maloney bougies.

All patients being considered for fundoplication to treat GERD After successful passage, the scope is removed, and sequential

must undergo a comprehensive evaluation to determine whether insertion of progressively larger dilators (starting at 32 French) into

there is indeed an anatomic substrate for their symptoms and what the stricture is attempted.The weight of the dilator alone should be](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acs0407-openesophagealprocedures-100726063211-phpapp02/85/Acs0407-Open-Esophageal-Procedures-4-320.jpg)

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 5

sufficient to effect its passage, with little or no forward force performed by the operating team. Insufflation should be done

applied. Although the patient will be able to swallow comfortably with as little air as is practical, particularly in the case of large

only after satisfactory passage of a dilator at least 48 French in cal- paraesophageal hernias. The extent of the pathologic condition is

iber, it is essential never to try to force passage.To this end, the sur- documented and the absence of malignancy verified.The stomach

geon must take careful note of the subtle signs of increasing resis- is decompressed with suction, and the endoscope is removed. An

tance transmitted through the dilator. Sequential dilation should orogastric tube is placed while the patient is supine.

be stopped whenever significant resistance is encountered or blood Tracheal intubation is performed with either a standard single-

streaks appear on the dilator. Sudden pain during dilation is an lumen endotracheal tube or a double-lumen tube. The former

ominous sign and calls for immediate investigation with a swallow requires that the ventilated left lung be retracted cephalad with

study using a water-soluble contrast agent (e.g., Gastrografin; moist packs during the procedure; the latter allows lung isolation

Schering AG, Berlin, Germany). Subcutaneous emphysema in the and is preferred by some surgeons. A Foley catheter is placed; cen-

neck or mediastinal air on a plain chest radiograph may also indi- tral venous access generally is not required. Subcutaneous heparin

cate an injury to the esophagus. Perforation must be definitively is administered for DVT prophylaxis, and pneumatic calf com-

ruled out before the patient can be discharged. pression devices are applied. Antibiotic prophylaxis is provided

Highly stenotic strictures that do not allow the passage of a [see 1:1 Prevention of Postoperative Infection].

standard adult endoscope may be associated with a distorted and The patient is positioned for a left thoracotomy. The table is

a steeply angulated esophagus. In such cases, the use of a pediatric flexed to distract the ribs. An axillary roll is placed to protect the

endoscope may permit directed placement of a guide wire right brachial plexus. The right leg is bent at hip and knee while

through the stricture; fluoroscopy is a useful adjunct for this pur- the left leg is kept straight. Pillows are placed between the legs, and

pose. A series of progressively larger Savary-Gillard dilators may all pressure points are padded.The arms are positioned so that the

then be passed over the guide wire to enlarge the lumen and allow humeri are at right angles to the chest and the elbows are bent 90º.

subsequent endoscopic biopsy. As a rule, much less tactile feed-

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

back is available during wire-guided dilation than during passage

of standard Maloney-Hurst bougies. Increased pressure is

required to pass the Savary-Gillard dilators because of the resis- Step 1: Incision and Entry into Chest

tance caused by the wire passing through the dilator itself. It is A standard left posterolateral thoracotomy is performed. The

essential that the wire be well lubricated and not be allowed to dis- latissimus dorsi is divided. The serratus fascia is incised, but the

lodge proximally between the sequential insertions of progressive- muscle itself can generally be preserved. For most patients, the

ly larger dilators.The caveats that apply to blind dilation also apply sixth interspace is the most appropriate incision site for exposing

to wire-guided dilation. the hiatus.The seventh interspace can also be used, particularly if

Patients whose esophagus can be dilated to 48 French and who the patient is tall or has a hyperextended chest as a result of chron-

are candidates for antireflux surgery may undergo subsequent ic pulmonary disease. The paraspinal muscles are elevated away

intraoperative dilation to 54 to 60 French. Patients who cannot be from the posterior aspect of the adjacent ribs, and a 1 cm segment

dilated to 48 French and fail to achieve comfortable swallowing of the rib below the selected interspace is resected to facilitate

should be classified as having a non-dilatable stricture and should exposure. The chest is then entered, and the lung and the pleural

be considered for transhiatal esophagectomy [see Resection of space are thoroughly inspected. The leaves of the retractor are

Esophagus and Proximal Stomach, below]. spread slowly over the course of the next several minutes so as not

to cause iatrogenic rib fractures.

Functional Evaluation

Esophageal manometry permits quantitative assessment of Step 2: Mobilization of Esophagus and Excision of Hernia Sac

peristalsis, a capability that is critically important for determining The inferior pulmonary ligament is divided with the electro-

which type of fundoplication is most suitable for reconstructing a cautery to the level of the inferior pulmonary vein [see Figure 4].

nonoccluding high-pressure zone at the esophagogastric junction. The mediastinal pleura overlying the esophagus is longitudinally

Stationary pH tests measure the capacity of the esophagus to clear incised to expose the esophagus from the level of the carina to the

acid, its sensitivity to instilled acid, the relationship of reflux diaphragm. Particular care is taken to avoid injury to the vagi.

episodes to body position, and the correlation between changes in Vessels supplying the esophagus and arising from the adjacent

esophageal pH and the subjective symptoms of heartburn. aorta are cauterized and divided. A few larger vessels may have to

Ambulatory 24-hour pH testing allows further quantification of be ligated with 2-0 silk.The esophagus is encircled just below the

reflux episodes with respect to duration, frequency, and associa- inferior pulmonary vein with a wide Penrose drain [see Figure 4].

tion with patient symptoms. The two vagi are mobilized and carried with the esophagus. (The

right vagus is located along the right anterior border of the des-

OPERATIVE PLANNING

cending aorta and can easily be missed.)

The transthoracic hiatus hernia repair may be completed with The esophagus is then elevated, and mobilization is circumfer-

either a partial fundoplication (as in the 240º Belsey Mark IV pro- entially completed in the direction of the diaphragm, starting from

cedure) or a complete fundoplication (as in the 360º Nissen pro- the level of the carina. In cases of giant paraesophageal hernia or

cedure). Acquired shortening of the esophagus may necessitate reoperation for a failed repair, the stomach will have a large intra-

lengthening of the esophagus by means of a Collis gastroplasty, in thoracic component. Dissection continues inferiorly to separate

which the portion of the gastric cardia along the lesser curvature the sac from the pericardium anteriorly and the aorta posteriorly.

and directly contiguous to the distal esophagus is fashioned into a The right pleura is closely approximated to the esophagus for 2 to

tube [see Operative Technique, Step 6a, below]. 5 cm above the diaphragm; in the presence of a substantial hiatal

A thoracic epidural catheter is placed for regional analgesia. hernia and its sac, it may be difficult to identify. The right pleura

General anesthesia is administered, and flexible esophagoscopy is should be gently dissected away from the sac without entry into](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acs0407-openesophagealprocedures-100726063211-phpapp02/85/Acs0407-Open-Esophageal-Procedures-5-320.jpg)

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 7

with a simple stitch of 4-0 silk. Mobilization is complete when the

fundus is restored to its original anatomic position and the greater

curvature can be followed down to the left gastroepiploic artery.

Step 5: Closure of Crura

Because the right crus is often quite attenuated, it is crucial to

incorporate an adequate amount of tissue into the repair. An Allis

or Babcock clamp is placed at the apex of the hiatus and into the

central tendon so that both crura can be placed under tension.

The esophagus is retracted anteriorly, and a No. 1 silk suture is

passed through the most posterior aspect of the left crus, with care

taken to avoid the adjacent spleen [see Figure 5]. A notched spoon

retractor is placed through the hiatus and into the abdomen

behind the left crus.The spleen is thus protected while the suture

is brought through the left crus.

Next, the suture is brought out through the right crus, with care

taken to prevent injury to the aorta or entry through the right

pleura.Three to five crural repair stitches are then placed at 1 cm

intervals, from posterior to anterior. The sutures should be stag-

gered slightly so that the needle entry points are not all in a

straight line; this measure helps prevent longitudinal shredding of

the muscle fibers when the sutures are placed under tension.The

sutures are held together with hemostats but left untied at this Figure 6 Transthoracic hiatal hernia repair. The anterior fat

point in the operation. pad is removed from the esophagus with sharp dissection, with

care taken to avoid injury to the vagi.

Placement of traction on the last suture should close the defect

while still allowing easy passage of one finger along the esophagus.

The final decision on whether to tie this last suture or to cut it out

is made later, after construction of the fundoplication. It is better Step 7: Fundoplication and Reduction of Wrap into Abdomen

to err on the side of an overly narrow opening: removing a suture The fundus is passed posteriorly behind the esophagus and

is easier than having to place an extra one at a time when expo- brought up against the anterior stomach, with care taken to avoid

sure is less than optimal. torsion of the fundal wrap.The fundus is then wrapped either over

the lower 2 cm of the esophagus, if no gastroplasty was done, or

Step 6: Assessment of Esophageal Length and Removal of over a 2 cm length of the gastroplasty tube while the bougie is in

Anterior Fat Pad place. The seromuscular layer of the fundus is approximated to

After placement of the crural stitches, an assessment of the that of the esophagus or the gastroplasty tube and that of the adja-

esophageal length is made. Ideally, the stomach can easily be cent anterior stomach with two interrupted 2-0 silk sutures [see

reduced into the abdomen without placing tension on the thoracic Figure 8]. When tied, the wrap should still be loose enough to

esophagus.When esophageal foreshortening is found, a Collis gas- accommodate a finger alongside the esophagus. The fundoplica-

troplasty is performed [see Step 6a, below]. tion sutures are again oversewn with a continuous seromuscular

If an esophageal stricture is present, the assistant performs dila- nonabsorbable monofilament suture. Two clips are placed at the

tion by passing a tapered bougie orally while the surgeon supports superior aspect of the wrap. These, along with the previously

the esophagus. The anteriorly located esophageal fat pad is placed clips, help confirm both the length and the location of the

removed in anticipation of the gastroplasty, with care taken not to wrap on chest x-ray.

injure the vagi located on either side [see Figure 6]. Once the fundoplication is complete, the dilator is removed and

the wrap is reduced into the abdomen. Two mattress sutures of

Step 6a: Collis Gastroplasty 2-0 polypropylene are placed to secure the top of the fundoplica-

In a Collis gastroplasty for a short esophagus, a stapler is used tion to the underside of the diaphragm. The crural sutures are

to form a 4 to 5 cm neoesophagus out of the proximal stomach, then sequentially tied, from the most posterior one to the most

thereby effectively lengthening the esophagus and transposing the anterior. When the final suture is tied, one finger should still be

esophagogastric junction more distally. A large-caliber Maloney able to pass through the hiatus alongside the esophagus.

bougie (54 French for women, 56 French for men) is placed in the

esophagus to prevent narrowing of the lumen as the stapler is Step 8: Drainage and Closure

fired. The bougie is advanced well into the stomach so that its A nasogastric tube is passed into the stomach and secured.

widest portion rests at the esophagogastric junction.The bougie is Hemostasis is verified, and a single thoracostomy tube is placed.

held against the lesser curvature, and the fundus is retracted away The wound is closed in layers. A chest x-ray is performed to veri-

at a right angle to the esophagus with a Babcock clamp. A 60 mm fy the position of the tubes and the location of the clips marking

gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) stapler loaded with 3.5 mm the wrap. The patient is then extubated in the OR and transport-

staples is applied immediately alongside the bougie on the greater ed to the recovery area.

curvature side [see Figure 7a] and fired, simultaneously cutting

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

and stapling the cardia. The staple line is oversewn with nonab-

sorbable 4-0 monofilament suture material on both sides [see Patients typically remain in the hospital for 5 days.The nasogas-

Figure 7b].Two metal clips are placed to mark the distal extent of tric tube is left on low suction and removed on postoperative day

the gastroplasty tube, denoting the new esophagogastric junction. 3. Patients then begin liquid oral intake, advancing to a full fluid](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acs0407-openesophagealprocedures-100726063211-phpapp02/85/Acs0407-Open-Esophageal-Procedures-7-320.jpg)

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 9

related to recurrent reflux, ulceration, or stricture usually responds become apparent only at the time of operation. Thoracic epidural

to dilation; reoperation is not required if the barium swallow shows analgesia should be administered for pain control. If an Ivor-Lewis

contrast flowing through the esophagus and an intact wrap beneath or thoracoabdominal approach is taken, a double-lumen endotra-

the diaphragm. Given that patients with longstanding reflux are at cheal tube should be placed for separate lung ventilation.

higher risk for dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma, it is

important to perform endoscopy to rule out malignancy. Imaging

Contrast esophagography, esophagoscopy with biopsy, and

OUTCOME EVALUATION

contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and the upper abdomen are

Transthoracic hiatal hernia repair yields good to excellent required before esophagectomy. The esophagogram identifies the

results in more than 85% of patients undergoing a primary repair. location of the tumor and may indicate whether it extends into the

Approximately 75% of patients who have previously undergone proximal stomach. Esophagoscopy allows direct assessment of the

hiatal hernia repair experience symptomatic improvement.2 mucosa, precise localization of the tumor, and collection of tissue

for histologic study. Retroflexion views of the stomach, after dis-

tention with air, are particularly important if proximal gastric inva-

Resection of Esophagus and Proximal Stomach sion is suspected, in which case esophagogastrectomy with recon-

In the remainder of the chapter, we describe the standard open struction of alimentary continuity by means of intestinal interpo-

techniques for resection of the esophagus and the esophagogastric sition may be required. In cases of midesophageal cancer, a bron-

junction. Transhiatal esophagectomy is commonly performed to choscopy is mandatory to rule out airway involvement. The cari-

treat end-stage benign esophageal disease and carcinomas of the na and the proximal left mainstem bronchus are the sites that are

cardia and the lower esophagus. Esophageal resection through a most at risk for local invasion.

combined laparotomy–right thoracotomy approach is ideal for Contrast-enhanced CT scans of the chest and abdomen are

cancers of the middle and upper esophagus. The gastric conduit standard.Thoracic and abdominal CT scans yield information on

may be anastomosed to the cervical esophagus either high in the the extent of any celiac or mediastinal adenopathy, the degree of

right chest (as in an Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy) or in the neck (as esophageal thickening, and the possibility of invasion of the adja-

in a transhiatal esophagectomy).The left thoracoabdominal approach cent aorta or tracheobronchial tree. The lung parenchyma is

is rarely used but may be indicated for resection of the distal esoph- assessed for metastatic nodules, as are the liver and the adrenal

agus and the proximal stomach in the case of a bulky tumor that glands. When the distal extent of tumor cannot be defined as a

is locally aggressive. result of near-complete obstruction on endoscopy, a prone

abdominal CT can help differentiate a tumor at the gastric cardia

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

from a collapsed but normal stomach. If the obstruction is not

Thorough preoperative preparation is essential for good post- complete, the stomach can be distended with air (through either

operative outcome. Smoking cessation and a graded regimen of the ingestion of effervescent granules or the passage of a small-

home exercise will help minimize postoperative complications and bore nasogastric tube) to improve visualization. A prone CT also

encourage early mobilization. Schematic diagrams have proved yields improved imaging of the gastrohepatic and celiac lymph

useful for educating patients and shaping their expectations about nodes by allowing the stomach to fall away from these adjacent

quality of life and ability to swallow after esophagectomy. structures. Metastatic cancer in the celiac lymph nodes portends

Illustrations, by emphasizing the anatomic relations, greatly facili- a very poor prognosis and is a contraindication to resection.

tate discussion of potential complications (e.g., hoarseness from PET scanning is useful for the detection of occult distant

recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, pneumothorax, anastomotic metastases that preclude curative resection. Suspicious areas

leakage, mediastinal bleeding, and splenic injury). should undergo needle biopsy or laparoscopic or thoracoscopic

Potential postoperative problems (e.g., reflux, regurgitation, assessment. Similarly, pleural effusions [see 4:4 Pleural Effusion]

early satiety, dumping, and dysphagia) must be discussed before must be tapped for cytologic evaluation. Invasion of mediastinal

operation. Such discussion is particularly relevant for patients structures and the presence of distant metastases are contraindi-

undergoing esophagectomy for early-stage malignant tumors or cations to transhiatal esophagectomy.

for high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s mucosa. These patients gen- At present, EUS, though quite sensitive for detection of parae-

erally have no esophageal obstruction and may be completely sophageal adenopathy, is incapable of differentiating reactive

asymptomatic; accordingly, their expectations about postoperative lymph nodes from nodes invaded by malignancy. CT and PET

function may be quite different from those of patients with pro- have limitations, and thus, locoregional involvement may not be

found dysphagia secondary to near-complete esophageal occlu- recognized before resection is attempted. In patients who are mar-

sion. Support groups in which patients with upcoming operations ginal candidates for surgical treatment and in whom metastatic

can contact patients that have already undergone treatment have disease is suspected, thoracoscopy and laparoscopy have been

proved to be highly beneficial to all parties. Realistic expectations advocated for histologic evaluation of mediastinal lymph nodes,

improve the chances of a satisfactory outcome. pleural or peritoneal abnormalities, and celiac nodes. Although

this approach adds to the cost of investigation, it can save the

Evaluation of Operative Risk patient from having to undergo a major operation for what would

Preoperative assessment should include a thorough review of the later prove to be an incurable condition.

patient’s cardiopulmonary reserve and an estimate of the level of

operative risk [see ECP:6 Risk Stratification, Preoperative Testing, and Neoadjuvant Therapy

Operative Planning]. Spirometry, arterial blood gas analysis, and Patients with esophageal cancer who are candidates for resec-

exercise stress testing should be considered. Even when a transhiatal tion may benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy and concurrent

esophagectomy without thoracotomy is planned, patients should be radiation therapy. In particular, patients with good performance

assessed with an eye to whether they can tolerate a laparotomy and status and bulky disease should be considered for such therapy.To

a thoracotomy, in case the latter is made necessary by findings that date, no randomized trials have conclusively demonstrated a sur-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acs0407-openesophagealprocedures-100726063211-phpapp02/85/Acs0407-Open-Esophageal-Procedures-9-320.jpg)

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 10

vival benefit with this approach, but several series have document- Flexible esophagoscopy is performed (if it was not previously per-

ed a 20% to 30% rate of complete response with no viable tumor formed by the surgical team). A nasogastric tube is placed before

found at the time of resection. After chemoradiation, patients are final positioning and draping.

restaged with a barium swallow and CT. PET scanning after treat- The patient is placed in the supine position with a small rolled

ment may yield spurious results, in that inflammatory conditions sheet between the shoulders. The arms are secured to the sides,

can mimic the increased tracer uptake seen in malignant tissue. and the head is rotated to the right with the neck extended. The

Microscopic disease cannot be assessed, and scarring from radia- neck, the chest, and the abdomen are prepared as a single sterile

tion may further confound the situation by preventing tracer field. The drapes are placed so as to expose the patient from the

uptake in areas that actually harbor malignancy. left ear to the pubis.The operative field is extended laterally to the

If there are no contraindications to surgical treatment, resection anterior axillary lines to permit placement of thoracostomy tubes

is scheduled 2 to 3 weeks after the completion of neoadjuvant as needed. A self-retaining table-mounted retractor is used to facil-

therapy. This interval allows time for patients to return to their itate upward and lateral traction along the costal margin.

baseline activity level and for any induced hematologic abnormal-

ities to be corrected. Previous chemoradiation therapy does not Ivor-Lewis Esophagectomy

make transhiatal esophagectomy significantly more difficult or At many institutions, Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy is preferred

complicated. Many tumors are downstaged and less bulky at the because it provides excellent direct exposure for dissection of the

time of resection. In centers with experience in this approach, the intrathoracic esophagus, in that it combines a right thoracotomy

rates of bleeding and anastomotic leakage remain low. with a laparotomy. This procedure should be considered when

there is concern regarding the extent of esophageal fixation with-

OPERATIVE PLANNING

in the mediastinum. One advantage of Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy

is that an extensive local lymphadenectomy can easily be per-

Transhiatal Esophagectomy formed through the right thoracotomy. Any attachments to medi-

In transhiatal esophagectomy, the stomach is mobilized through astinal structures can be freed under direct vision. Whether any

a short upper midline laparotomy, the esophagus is mobilized regional lymph node dissection is necessary is highly controversial;

from adjacent mediastinal structures via dissection through the no significant survival advantage has yet been demonstrated.

hiatus without the use of a thoracotomy, and the stomach is trans- Long-term survival after Ivor-Lewis resection is equivalent to that

posed through the posterior mediastinum and anastomosed to the after transhiatal esophagectomy.3

cervical esophagus at the level of the clavicles. The main advan- The main disadvantages of the Ivor-Lewis procedure are (1) the

tages of this approach are (1) a proximal surgical margin that is physiologic impact of the two major access incisions employed (a

well away from the tumor site, (2) an extrathoracic esophagogas- right thoracotomy and a midline laparotomy) and (2) the location

tric anastomosis that is easily accessible in the event of complica- of the anastomosis (in the chest, at the level of the azygos vein).

tions, and (3) reduced overall operative trauma. Single-center stud- Incision-related pain may hinder deep breathing and the clearing

ies throughout the world have shown transhiatal esophagectomy to of bronchial secretions, resulting in atelectasis and pneumonia.

be safe and well tolerated, even in patients who may have signifi- Complications of the intrathoracic anastomosis may be hard to

cantly reduced cardiopulmonary reserve. Long-term survival is manage. Although the anastomotic leakage rate associated with

equivalent to that reported after transthoracic esophagectomy. Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy has typically been 5% or lower—and

Although transhiatal esophagectomy has been used for resec- thus substantially lower than the rate cited for the cervical anasto-

tion of tumors at any location in the esophagus, it is best suited for mosis after transhiatal esophagectomy—intrathoracic leaks are

resection of tumors in the lower esophagus and at the esopha- much more dangerous and difficult to handle than intracervial

gogastric junction. It should also be considered the operation of leaks. In many cases, drainage of the leak will be incomplete and

choice for certain advanced nonmalignant conditions of the empyema will result. Reoperation may prove necessary to manage

esophagus. Nondilatable strictures of the esophagus may occur as mediastinitis.

an end-stage complication of gastroesophageal reflux. Intractable

reflux after failed hiatal hernia repair may not be amenable to fur- Left Thoracoabdominal Esophagogastrectomy

ther attempts at reconstruction of the esophagogastric junction The left thoracoabdominal approach is indicated for resection

and thus may call for esophagectomy. Because of the high cervical of the distal esophagus and the proximal stomach when removal

anastomosis, a transhiatal esophagectomy is less likely to predis- of the stomach necessitates the use of an intestinal substitute to

pose to postoperative reflux and recurrent stricture formation than restore swallowing. If the proximal stomach must be resected for

a transthoracic esophagectomy would be. Achalasia may result in adequate resection margins to be obtained, then the distal stom-

a sigmoid megaesophagus and dysphagia that cannot be managed ach may be anastomosed to the esophagus in the chest.This oper-

without removal of the esophagus. Transhiatal esophagectomy ation is frequently associated with significant esophagitis from bile

permits complete removal of the thoracic esophagus and, in the reflux, and dysphagia is common. Consequently, many surgeons

majority of patients, restoration of comfortable swallowing with- prefer to resect the entire stomach and the distal esophagus and

out the need for a thoracotomy. then to restore swallowing with a Roux-en-Y jejunal interposition

Generally, patients are admitted to the hospital on the day of the anastomosed to the residual thoracic esophagus.

operation.Thoracic epidural analgesia is administered, both intra-

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

operatively and postoperatively, and appropriate antibiotic pro-

phylaxis is provided [see 1:1 Prevention of Postoperative Infection].

Heparin, 5,000 U subcutaneously, is given before induction, and Transhiatal Esophagectomy

pneumatic calf compression devices are applied. A radial artery Transhiatal esophagectomy is best understood as consisting of

catheter is placed to permit continuous monitoring of blood pres- three components: abdominal, mediastinal, and cervical. The ab-

sure. Central venous access is rarely required. General anesthesia dominal portion involves mobilization of the stomach, pyloromy-

is administered via an uncut single-lumen endotracheal tube. otomy, and placement of a temporary feeding jejunostomy.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acs0407-openesophagealprocedures-100726063211-phpapp02/85/Acs0407-Open-Esophageal-Procedures-10-320.jpg)

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 11

Step 1: incision and entry into peritoneum A midline Dissection then proceeds along the greater curvature toward

laparotomy is performed from the tip of the xiphoid to the umbili- the pylorus. The omentum is mobilized from the right gastroepi-

cus.The peritoneum is opened to the left of the midline so that the ploic artery.Vessels are ligated between 2-0 silk ties, and great care

falciform and the preperitoneal fat may be retracted en bloc to the is exercised to avoid placing excessive traction on the arterial

right. Body wall retractors are placed at 45º angles from the mid- arcade. A 1 cm margin is always maintained between the line of

line to elevate and distract both costal margins.The retractors are dissection and the right gastroepiploic artery. Venous injuries, in

placed so as to lift up the costal margin gently and open the particular, can occur with injudicious handling of tissue. The

wound. The abdomen is then inspected for metastases. ultrasonic scalpel is particularly efficient and effective for mobi-

lization of the stomach; again, this instrument must be applied

Step 2: division of gastrohepatic ligament and mobiliza- well away from the gastroepiploic arcade. Dissection is continued

tion of distal esophagus The left lobe of the liver is mobilized rightward to the level of the pylorus. It should be noted that the

by dividing the triangular ligament, then folded to the right and location of the gastroepiploic artery in this area may vary; often, it

held in this position with a moist laparotomy pad and a deep-blad- is at some unexpected distance from the stomach wall. Posterior

ed self-retaining retractor. Next, the gastrohepatic ligament is divided. adhesions between the stomach and the pancreas are lysed so that

Occasionally, there is an aberrant left hepatic artery arising from the lesser sac can be completely opened.

the left gastric artery [see Figure 9].The peritoneum over the right The assistant’s left hand is then placed into the lesser sac to

crus is incised, and the hiatus is palpated; the extent and mobility retract the stomach gently to the right and place the short gastric

of any tumor may then be assessed. The peritoneum over the left vessels on tension. The Penrose drain previously placed around

crus is similarly divided, and the esophagus is encircled with a 2.5 cm the esophagus facilitates exposure by retracting the cardia to the

Penrose drain. Traction is applied to draw the esophagogastric right. Dissection along the greater curvature proceeds cephalad.

junction upward and to the right; this measure facilitates exposure The vessels are divided well away from the wall of the stomach to

of the short gastric arteries coursing to the fundus and the cardia. prevent injury to the fundus. Clamps should never be placed on

the stomach. A high short gastric artery is typically encountered

Step 3: mobilization of stomach The greater curvature of just adjacent to the left crus. Precise technique is required to pre-

the stomach is inspected and the right gastroepiploic artery pal- vent injury to the spleen. The Penrose drain [see Step 2, above] is

pated.The lesser sac is generally entered near the midpoint of the exposed as the peritoneum is opened over the left crus.

greater curvature. The transition zone between the right gas- Mobilization of the proximal stomach and liberation of the distal

troepiploic arcade and the short gastric arteries is usually devoid esophagus are thereby completed.

of blood vessels. A moist sponge is placed behind the spleen to ele- Once the stomach has been completely mobilized along the

vate it and facilitate subsequent control of the short gastric vessels. greater curvature, it is elevated and rotated to the right [see Figure

Divided Left

Gastric Vessels

Lesser Omentum

Divided

Figure 9 Transhiatal esophagec- Greater Omentum

tomy. The duodenum is mobilized, Divided

and the gastrohepatic and gastro-

colic omenta are divided.

Intact Right

Gastroepiploic

Vessels](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acs0407-openesophagealprocedures-100726063211-phpapp02/85/Acs0407-Open-Esophageal-Procedures-11-320.jpg)

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 12

Hepatic Splenic

Artery Artery

E

Intact Right

Gastroepiploic

Artery

Figure 10 Transhiatal esophagectomy. After the stomach has been completely mobilized A

along the greater curvature, it is elevated and rotated to the right. The left gastric vessels

are suture-ligated and divided. A 1 cm margin of the diaphragmatic crura is taken in con-

tinuity with the esophagogastric junction, providing ample clearance of the tumor and

improved exposure of the lower mediastinum.

10]; the left gastric artery and associated nodal tissues can then be Dissection is extended toward the duodenum with the aid of a

visualized via the lesser sac. The superior edge of the pancreas is fine-tipped right-angle clamp. The duodenal submucosa, recog-

visible, and the remaining posterior attachments of the stomach nizable by its fatty deposits and yellow coloration, is exposed for

are divided along the hiatus and the left crus.These may be quite approximately 0.5 cm. The duodenal submucosa is usually much

extensive if there has been a history of pancreatitis or preoperative more superficial than expected, and accidental entry into the duo-

radiation therapy. denum often occurs just past the left edge of the circular muscle

If the operation is being done for malignant disease, a final of the pylorus. Releasing the tension on the traction sutures helps

determination of resectability can be made at this point. Tumor the surgeon visualize the proper depth of dissection. Should entry

fixation to the aorta or the retroperitoneum can be assessed. Celiac into the lumen occur, a simple repair using interrupted fine

and paraortic lymph nodes can be palpated and, if necessary, sent monofilament (4-0 or 5-0 polypropylene) sutures to close the

for biopsy. The left gastric artery and vein are then ligated proxi- mucosa is performed. Small metal clips are applied to the knots of

mally, either through the lesser sac or directly through the divided the traction sutures before removal of the ends; these clips serve

gastrohepatic ligament. All nodal tissue is dissected free in antici- to indicate the level of the pyloromyotomy on subsequent radi-

pation of subsequent removal en bloc with the specimen. ographic studies.

Step 4: mobilization of duodenum and pyloromyotomy Step 5: feeding jejunostomy Placement of a standard

The duodenum is mobilized with a Kocher maneuver. Careful Weitzel jejunal feeding tube approximately 30 cm from the liga-

attention to the superior extent of this dissection is critical. ment of Treitz completes the abdominal portion of the transhiatal

Adhesions to either the porta hepatis or the gallbladder must be esophagectomy.

divided to ensure that the pylorus is sufficiently freed for later

migration to the diaphragmatic hiatus. Step 6: exposure and encirclement of cervical esophagus

Gastric drainage is provided by a pyloromyotomy. Two figure- The cervical esophagus is exposed through a 6 cm incision along

eight traction sutures of 2-0 cardiovascular silk are placed deeply the anterior edge of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle [see Figure

through both the superior and the inferior border of the pylorus; 1] that is centered over the level of the cricoid cartilage. The

traction is then placed on these sutures to provide both exposure platysma is divided to expose the omohyoid, which is divided at its

and some degree of hemostasis.The pyloromyotomy is begun 2 to tendon.The strap muscles are divided low in the neck.The esoph-

3 cm on the gastric side of the pylorus. The serosa and the mus- agus and its indwelling nasogastric tube can be palpated.

cle are divided with a needle-tipped electrocautery to expose the The carotid sheath is retracted laterally, and blunt dissection is

submucosa; generally, these layers of the stomach are robust, mak- employed to reach the prevertebral fascia. The inferior thyroid

ing the proper plane easy to find. artery is ligated laterally; the recurrent laryngeal nerve is visible just](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acs0407-openesophagealprocedures-100726063211-phpapp02/85/Acs0407-Open-Esophageal-Procedures-12-320.jpg)

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 13

deep and medial to this vessel. No retractor other than the surgeon’s

finger should be applied medially: traction injury to the recurrent

laryngeal nerve will result in both vocal cord palsy and uncoordi-

nated swallowing with aspiration. In particular, metal retractors

must not be used in this area. The tracheoesophageal groove is

incised close to the esophageal wall while gentle finger traction is

applied cephalad to elevate the thyroid cartilage toward the right.

This measure usually suffices to define the location of the nerve.

The esophagus is then encircled by passing a right-angle clamp

posteriorly from left to right while the surgeon’s finger remains in

the tracheoesophageal groove.The tip of the clamp is brought into

the pulp of the fingertip.The medially located recurrent laryngeal

nerve and the membranous trachea are thereby protected from

injury.The clamp is brought around, and a narrow Penrose drain

is passed around the esophagus [see Figure 11]. Blunt finger dis-

section is employed to develop the anterior and posterior planes

around the esophagus at the level of the thoracic inlet.

Step 7: mediastinal dissection Some authors describe this

portion of the procedure as a blunt dissection, but in fact, the vast

majority of the mediastinal mobilization is done under direct

vision. Narrow, long-handled, handheld, curved Harrington

retractors are placed into the hiatus and lifted up to expose the

distal esophagus. Caudal traction is placed on the esophagus,

allowing excellent visualization of the hiatus and the distal esoph-

agus. Long right-angle clamps are used to expose these attach-

ments.Vascularity in this area is often minimal, and hemostasis can

easily be achieved with either the electrocautery or the ultrasonic

Cricopharyngeal Figure 12 Transhiatal esophagectomy. The plane posterior to the

Muscle esophagus is developed by placing the surgeon’s right hand into

the hiatus along the prevertebral fascia. A moist sponge stick is

placed through the cervical incision posterior to the esophagus,

and the posterior plane is completed.

scalpel. The left crus can be divided to facilitate exposure. Para-

esophageal lymph nodes are removed either en bloc or as separate

specimens. Dissection is continued cephalad with the electro-

cautery and a long-handled right-angle clamp. The two vagi are

divided, and the periesophageal adhesions are lysed. Mobilization

of the distal esophagus under direct vision is thus completed up to

the level of the carina.

Three specific maneuvers are now carried out. First, the plane

posterior to the esophagus is developed [see Figure 12]. The sur-

geon’s right hand is advanced palm upward into the hiatus, with

the fingers closely applied to the esophagus. The volar aspects of

the fingers run along the prevertebral fascia, elevating the esoph-

agus off the spine. A moist sponge stick is placed through the cer-

vical incision, also posterior to the esophagus. The sponge is

Left Recurrent advanced toward the right hand, which is positioned within the

Laryngeal Nerve mediastinum. As the sponge is advanced into the right palm, the

posterior plane is completed. A 28 French mediastinal sump is

then passed from the cervical incision into the abdomen along the

posterior esophageal wall and attached to suction. Any blood loss

from the mediastinum is collected and monitored.

Figure 11 Transhiatal esophagectomy. Once the cervical esoph-

Second, the anterior plane is developed [see Figure 13]. This is

agus is exposed through an incision along the left sternocleido- often much more difficult than developing the posterior plane

mastoid muscle, strap muscles are divided and retracted, and the because the left mainstem bronchus may be quite close to the

cervical esophagus is dissected away from the left and right esophagus. Again, the surgeon’s right hand is placed through the

recurrent laryngeal nerves. hiatus, but it is now palm down and anterior to the esophagus.The](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acs0407-openesophagealprocedures-100726063211-phpapp02/85/Acs0407-Open-Esophageal-Procedures-13-320.jpg)

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 14

fingertips enter the space between the esophagus and the left main- Pericardium Vagus Nerves

stem bronchus.The hand is gently advanced, and the airway is dis- Carina Clipped

placed anteriorly. A blunt curved suction handle is employed from

above as a substitute finger. It is advanced along the anterior aspect

of the esophagus through the cervical incision. The right hand

guides the tip of the suction handle beneath the bronchus. Lateral

displacement of the handle allows further mobilization of the

bronchus away from the esophagus. Completion of the anterior

and posterior planes usually results in a highly mobile esophagus.

Third, the lateral attachments of the upper and middle esopha-

gus are divided. Upward traction is applied with the Penrose drain

previously placed around the cervical esophagus, allowing further

dissection at the level of the thoracic inlet. Lateral attachments are

pushed caudally into the mediastinum, and traction applied to the

esophagus from below allows these attachments to be visualized

inferiorly through the hiatus, then isolated with long right-angle

clamps and divided with the electrocautery. Caution must be exer-

cised so as not to injure the azygos vein. Dissection on the right

side must therefore be kept close to the esophagus. Once the last

lateral attachment is divided, the esophagus is completely free and

can be advanced into the cervical wound.

Close monitoring of arterial blood pressure is maintained

throughout.Transient hypotension may occur as a result of medi-

astinal compression and temporary impairment of cardiac venous

return as the surgeon’s hand or retractors are passed through the

hiatus. Vasopressors are never required for management: simple

Figure 14 Transhiatal esophagectomy. The esophagus is divided

in the neck and delivered into the abdomen. Retractors are

placed in the hiatus, and any vessels entering into the esophagus

are clipped and divided. The vagi are also clipped and divided.

repositioning of the retractors or removal of the dissecting hand

usually results in prompt restoration of normal BP. Placement of

the patient in a slight Trendelenburg position is often helpful.

Step 8: proximal transection of esophagus and delivery

into abdomen The nasogastric tube is retracted to the level of

the cricopharyngeus, and the esophagus is divided with a cutting

stapler 5 to 6 cm distal to the muscle. The esophagus is then

removed via the abdomen [see Figure 14]. Retractors are placed in

the hiatus, and the mediastinum is inspected for hemostasis. The

sump is removed. Both pleurae are inspected.The lungs are inflat-

ed so that it can be determined which pleural space requires tho-

racostomy drainage. The mediastinum is packed with dry lapa-

rotomy pads from below. A narrow pack is placed into the thoracic

inlet from above. Chest tubes are then placed as required along the

inframammary crease in the anterior axillary line. The drainage

from these tubes should be closely monitored throughout the rest

of the operation to ensure that any bleeding from the mediastinal

dissection does not go unnoticed.

Step 9: excision of specimen and formation of gastric

tube The gastric fundus is grasped, and gentle tension is applied

along the length of the stomach. The esophagus is held at right

angles to the body of the stomach, and the fat in the gastrohepat-

ic ligament is elevated off the lesser curvature; all lymph nodes are

Figure 13 Transhiatal esophagectomy. The anterior plane is

thus mobilized. A point approximately midway along the lesser

developed by placing the surgeon’s right hand through the hiatus

anterior to the esophagus. The fingertips enter the space between

curvature is selected. The blood vessels traversing this area from

the esophagus and the left mainstem bronchus, to be met by a the right gastric artery are ligated to expose the lesser curvature.

blunt suction handle passed downward through the cervical inci- The distal resection margin is then marked; it should be 4 to 6 cm

sion. The lateral attachments of the esophagus are divided from from the esophagogastric junction, extending from the selected

above downward as far as the aortic arch. point on the lesser curvature to a point medial to the fundus. A 60](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acs0407-openesophagealprocedures-100726063211-phpapp02/85/Acs0407-Open-Esophageal-Procedures-14-320.jpg)

![© 2006 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

4 THORAX 7 OPEN ESOPHAGEAL PROCEDURES — 15

mm GIA stapler loaded with 3.5 mm staples is then used to tran- ensure that injury to the gastroepiploic arcade does not occur at

sect the proximal stomach, proceeding from the lesser curvature this late point in the procedure.The hiatus is narrowed, but not so

toward the fundus [see Figure 15]. Resection of the cardia along much that three fingers cannot be easily passed alongside the gas-

with the adjacent portion of the lesser curvature effectively con- tric conduit. This reconstitution will help prevent herniation of

verts a J-shaped stomach into a straight tube. other abdominal contents alongside the gastric conduit. The liver

For maximizing the length of the gastric tube, there are several is returned to its anatomic position, thus also preventing any sub-

technical points that are critical. Tension must be maintained on sequent herniation of bowel into the chest.The pyloromyotomy is

the stomach as the stapler is serially applied cephalad.The stapler generally found at the level of the diaphragm. The laparotomy is

should be simply placed on the stomach and fired: no attempt then closed in the usual fashion.The viability of the fundus in the

should be made to telescope tissue into the jaws, because to do so neck incision is checked periodically as the abdominal portion of

would effectively reconstitute the curve of the stomach and dimin- the procedure is completed.

ish its upward reach. Typically, three staple loads are required.

The specimen is removed, and frozen section examination is Step 11: cervical esophagogastric anastomosis The con-

done on the distal margin.The completed staple line is then over- struction of the esophagogastric anastomosis is the most impor-

sewn with a continuous Lembert suture of 4-0 polypropylene. Once tant part of the entire operation: any anastomotic complication

again, tension is maintained along the stomach to prevent any fore- will greatly compromise the patient’s ability to swallow comfort-

shortening of the lesser curvature.The use of two separate sutures, ably. Accordingly, meticulous technique is essential.

each reinforcing half of the staple line, is helpful in this regard. A seromuscular traction suture of 4-0 polyglactin is placed

through the anterior stomach at the level of the clavicle and drawn

Step 10: advancement of stomach into chest or neck upward, thus elevating the fundus into the neck wound and great-

The mediastinal packs are removed, and hemostasis is verified in ly facilitating the anastomosis.The pack behind the fundus is then

the chest.The stomach is inspected as well.The ends of any short removed.

gastric vessels that were divided with the ultrasonic scalpel are The site of the anterior gastrotomy is then carefully selected: it

now tied so that subsequent manipulation does not precipitate should be midway between the oversewn lesser curvature staple

bleeding. The stomach is oriented so that the greater curvature is line and the greater curvature of the fundus (marked by the ligat-

to the patient’s left.There must be no torsion.The anterior surface ed ends of the short gastric vessels). The staple line on the cervi-

of the fundal tip should be marked with ink so that proper orien- cal esophagus is removed, and the anterior aspect of the esopha-

tation of the stomach can be confirmed after its passage into the gus is grasped with a fine-toothed forceps at the level of the

neck. The stomach can usually be advanced through the posteri- planned gastrotomy. A straight DeBakey forceps is then applied

or mediastinum without any traction sutures or clamps. The sur- across the full width of the esophagus to act as a guide for division.

geon’s hand is placed palm down on the anterior surface of the The esophagus is cut with a new scalpel blade at a 45º angle so

stomach, with the fingertips about 5 cm proximal to the tip of the that the anterior wall is slightly longer than the posterior wall; the

fundus. The hand is then gently advanced through the chest,

pushing the stomach ahead of itself. The tip of the fundus is gen-

tly grasped with a Babcock clamp as it appears in the neck.To pre-

vent trauma at this most distant aspect of the gastric tube, the

clamp should not be ratcheted closed.

No attempt should be made to pull the stomach up into the

neck: the position of the fundus is simply maintained as the sur-

geon’s hand is removed from the mediastinum. Further length in

the neck can usually be gained by gently readvancing the hand

along the anterior aspect of the stomach.This measure uniformly

distributes tension along the tube and ensures proper torsion-free

orientation in the chest. The stomach is pushed up into the neck

rather than drawn up by the clamp.

A useful alternative approach for positioning the gastric tube

involves passing a large-bore Foley catheter through the medi-

astinum from the neck incision. The balloon is inflated, and a 50

cm section of a narrow plastic laparoscopic camera bag is tied

onto the catheter just above the balloon. The gastric tube is posi-

tioned within the bag, and suction is applied through the catheter,