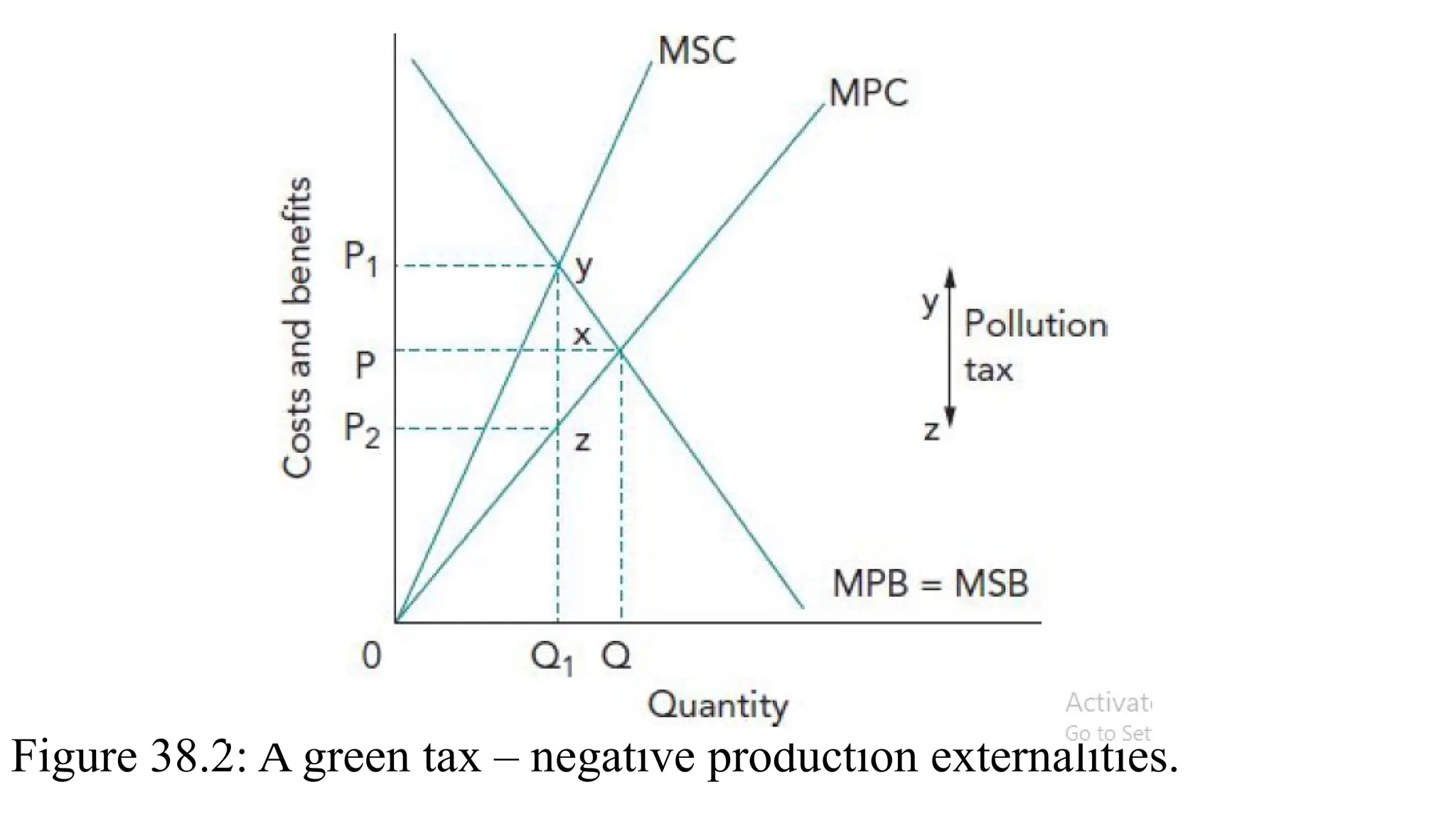

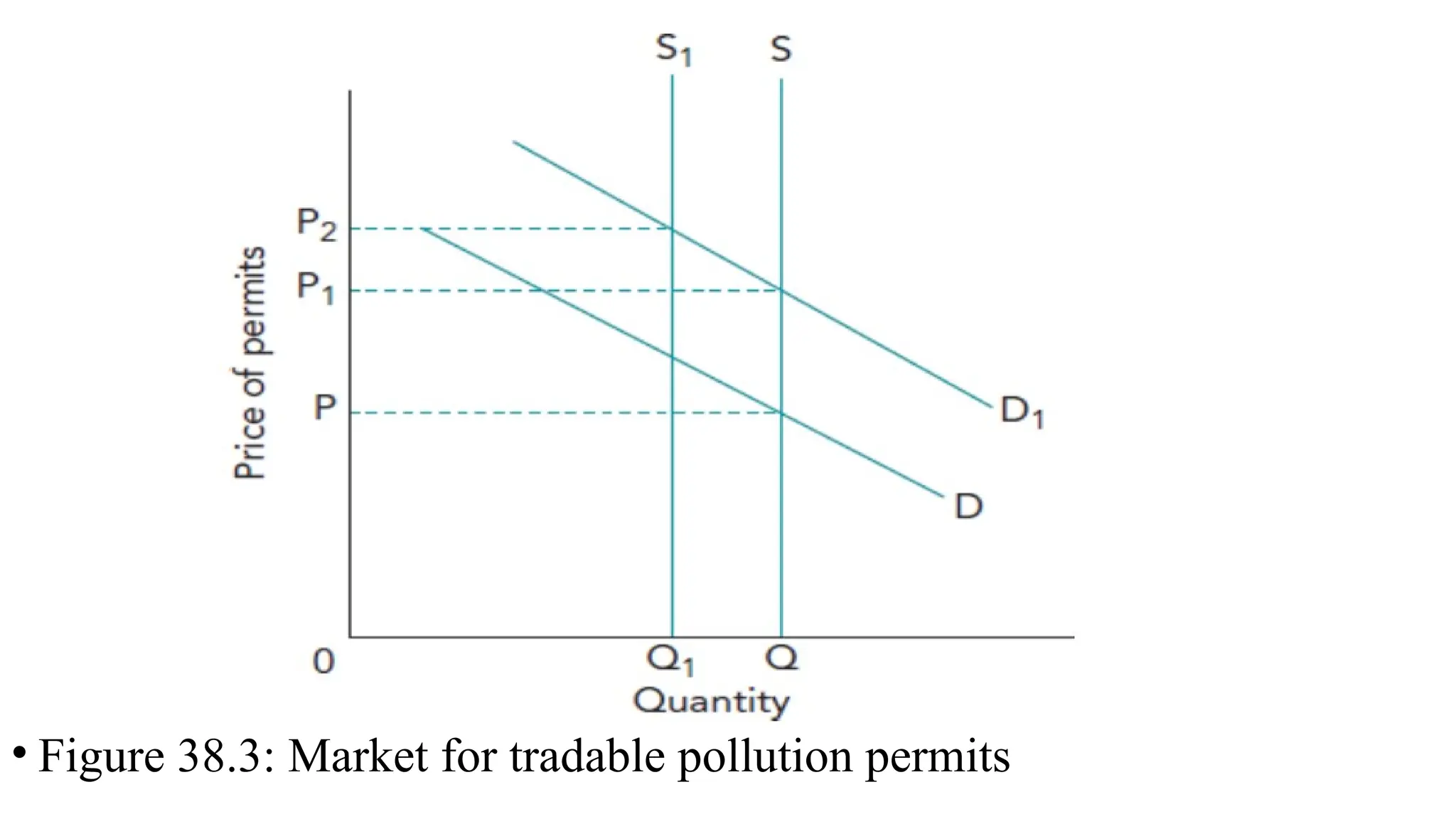

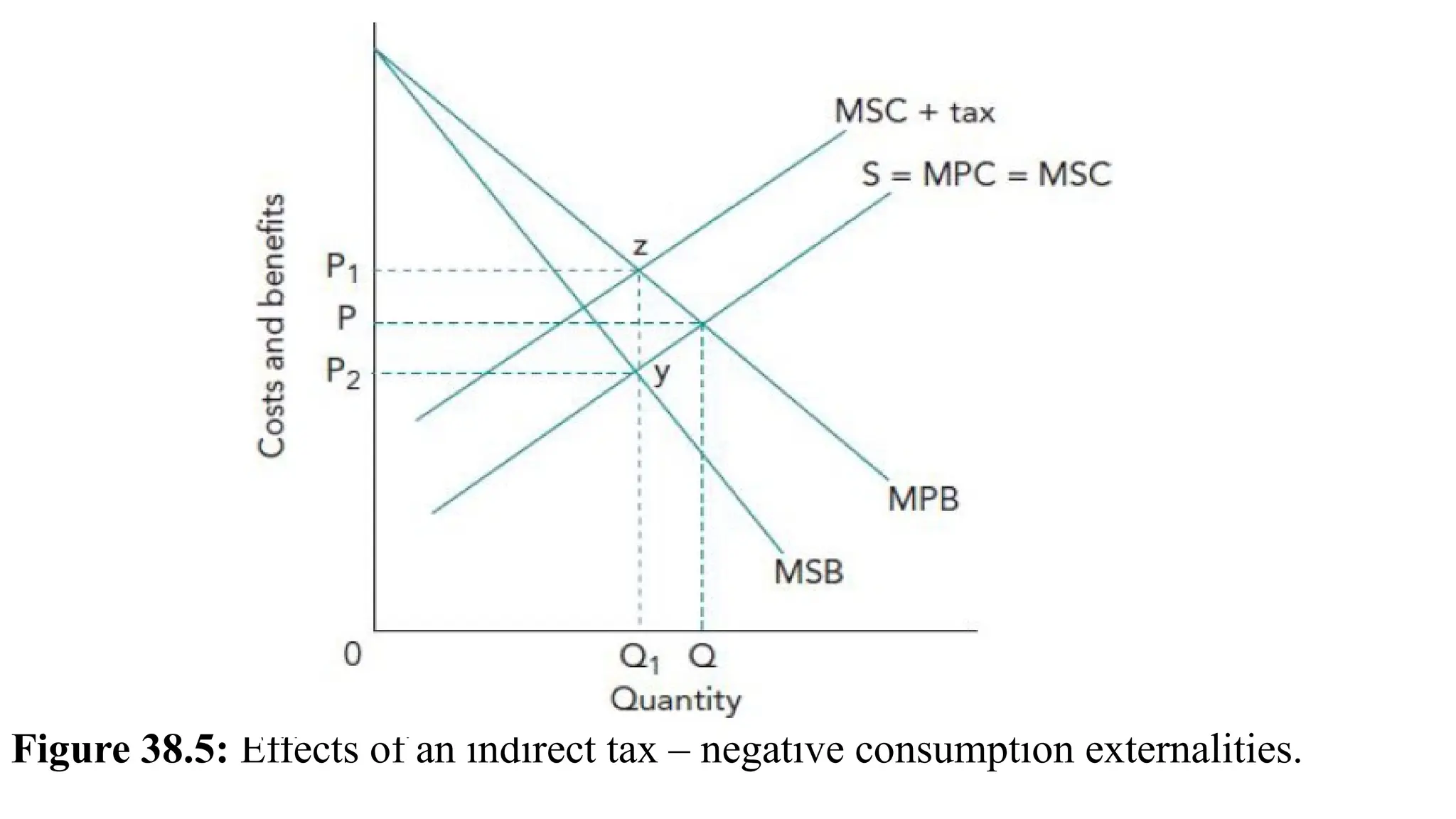

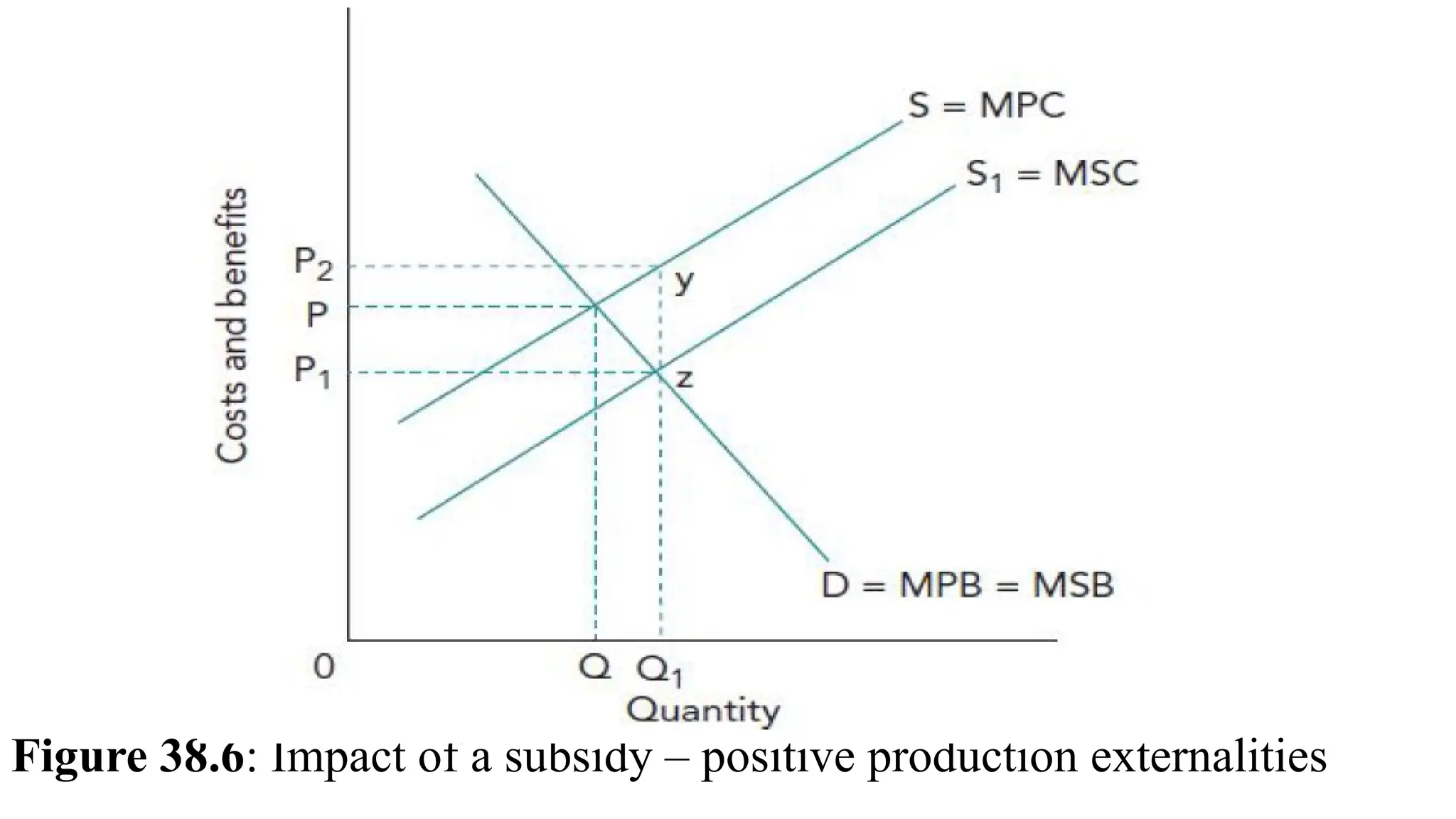

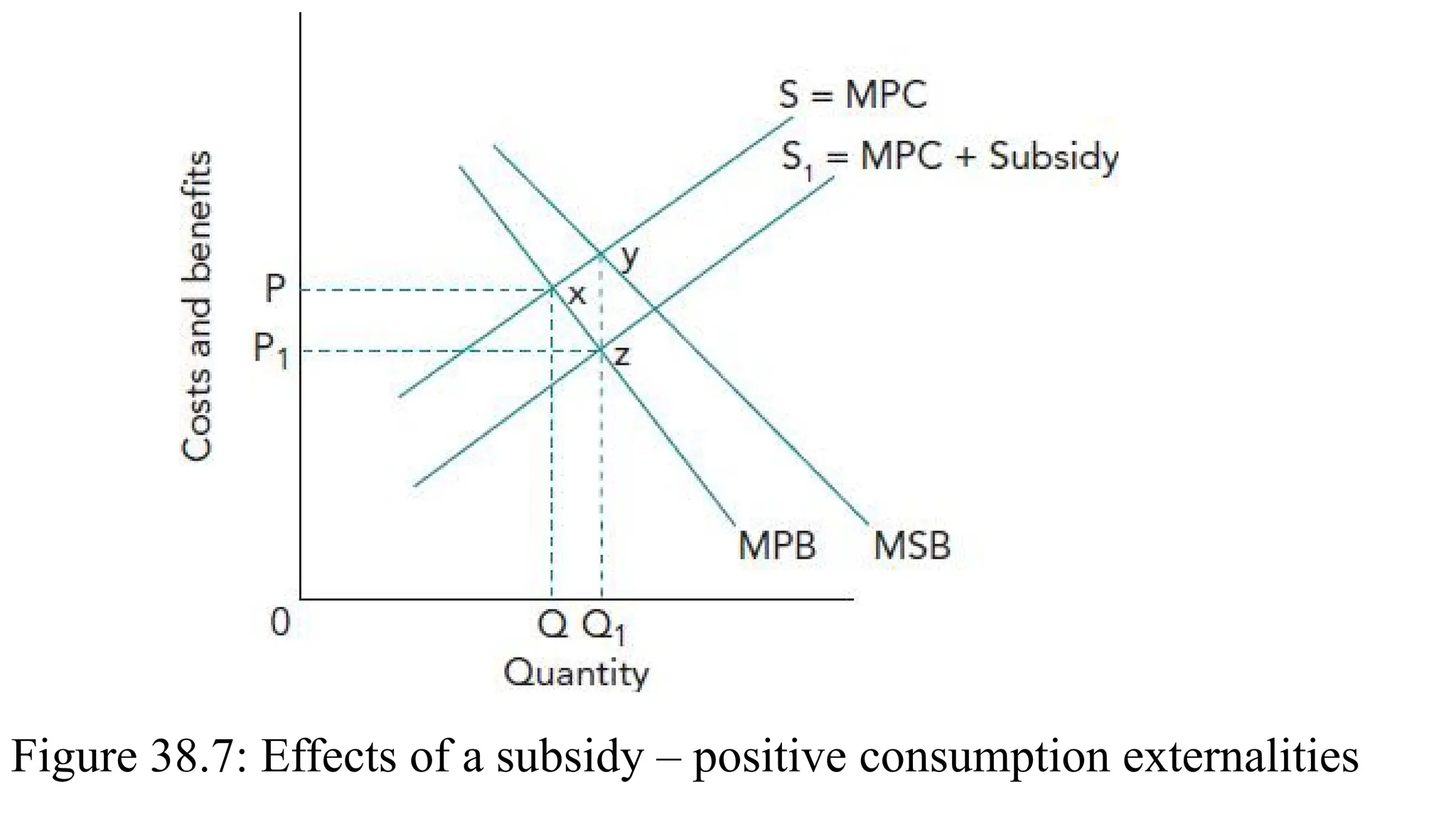

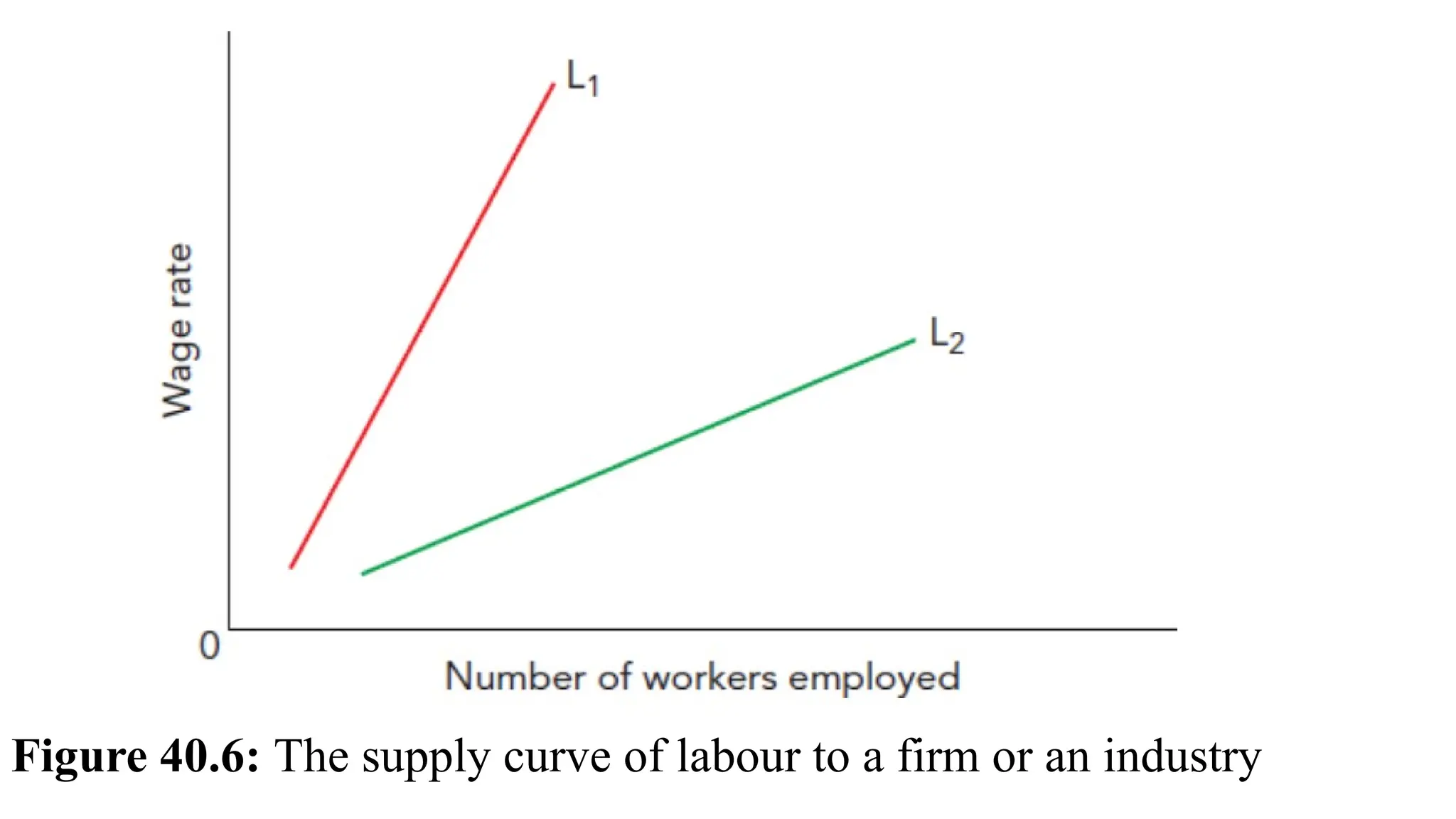

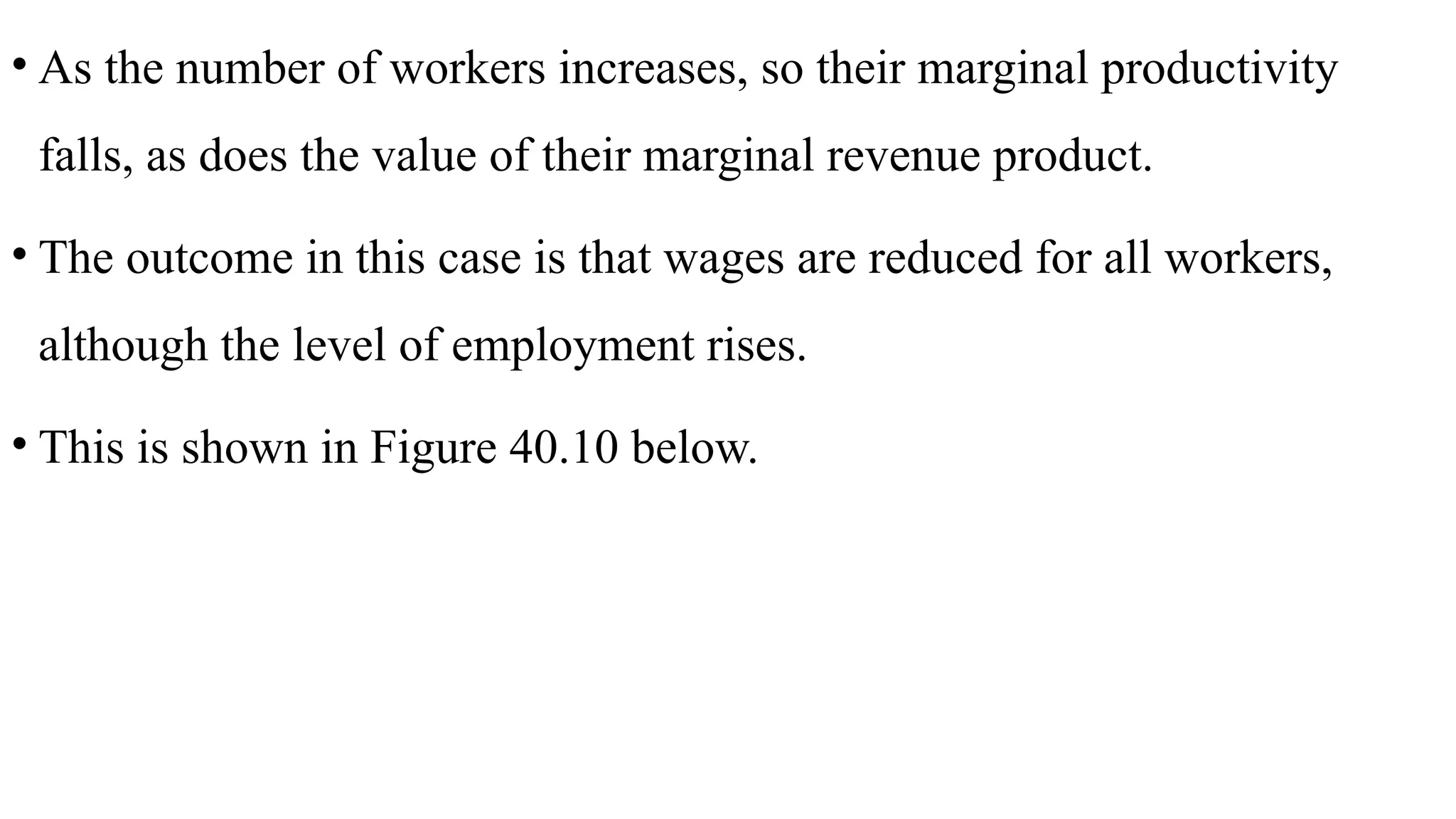

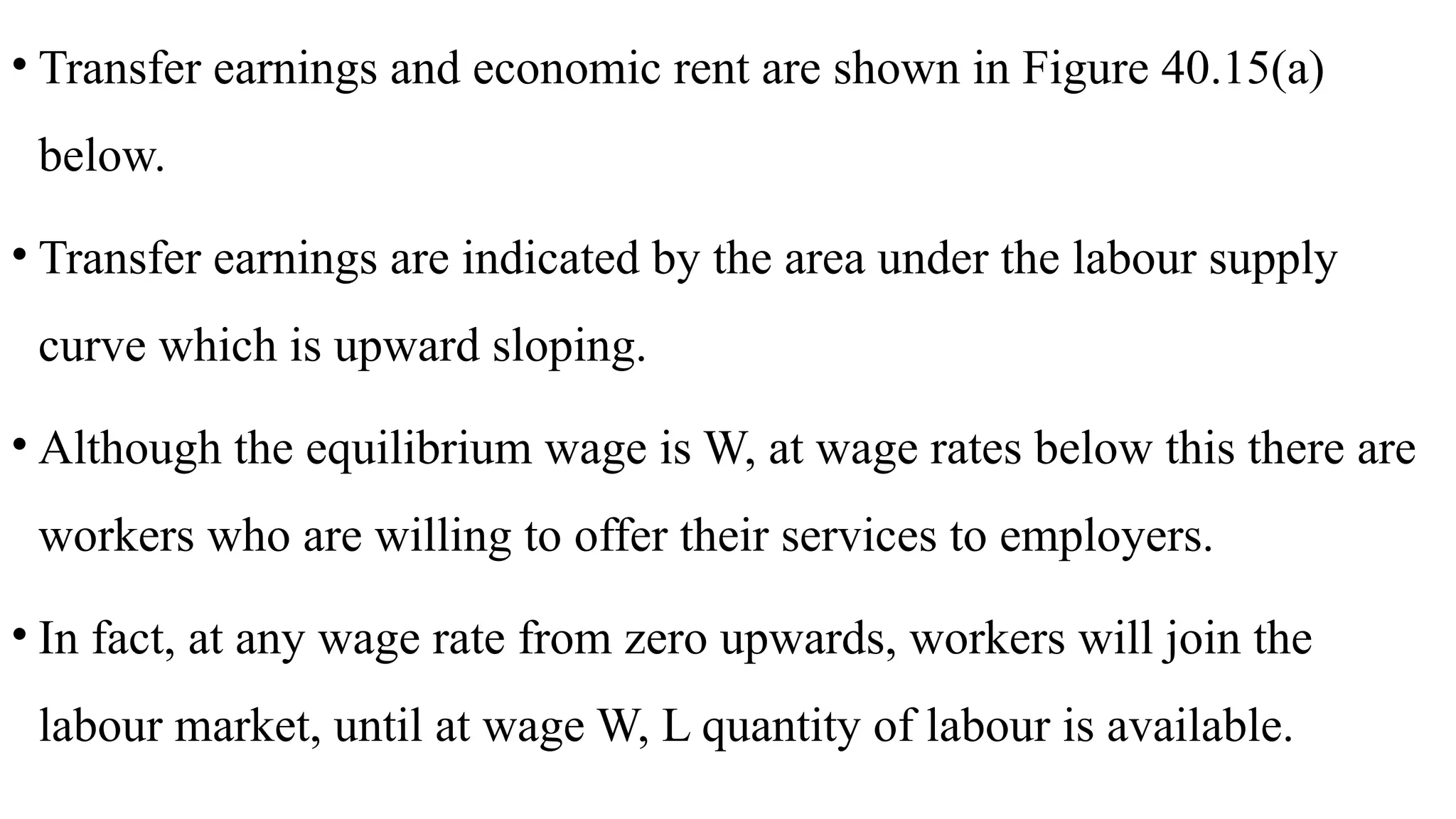

Chapter 38 discusses various government interventions aimed at correcting market failures, particularly those arising from negative and positive externalities, using tools like taxes, subsidies, regulations, and pollution permits. It evaluates the effectiveness of these tools and the potential for government failure when estimating external costs or implementing regulations. The chapter emphasizes the role of behavioral insights and direct provision of public goods and merit goods as crucial strategies for achieving efficient resource allocation.