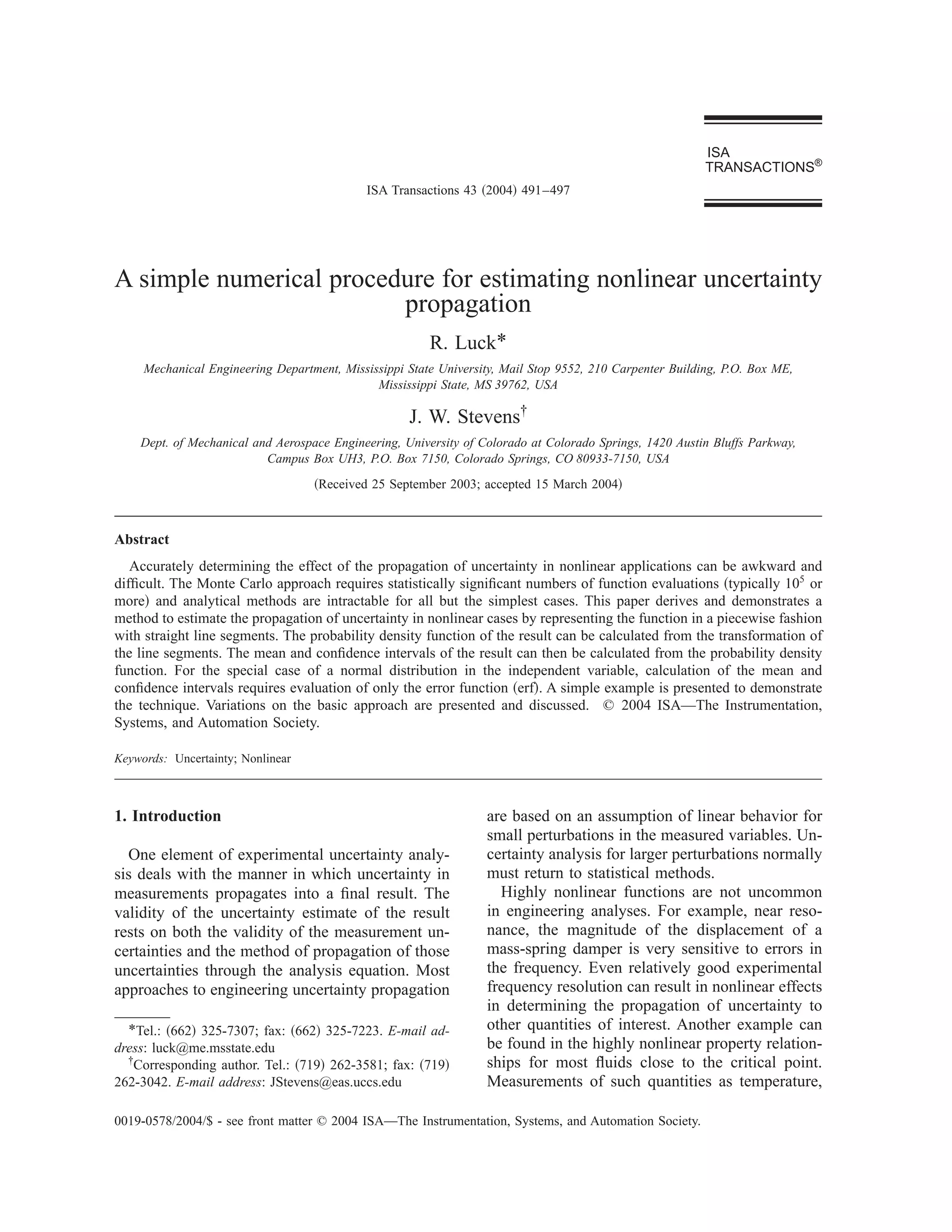

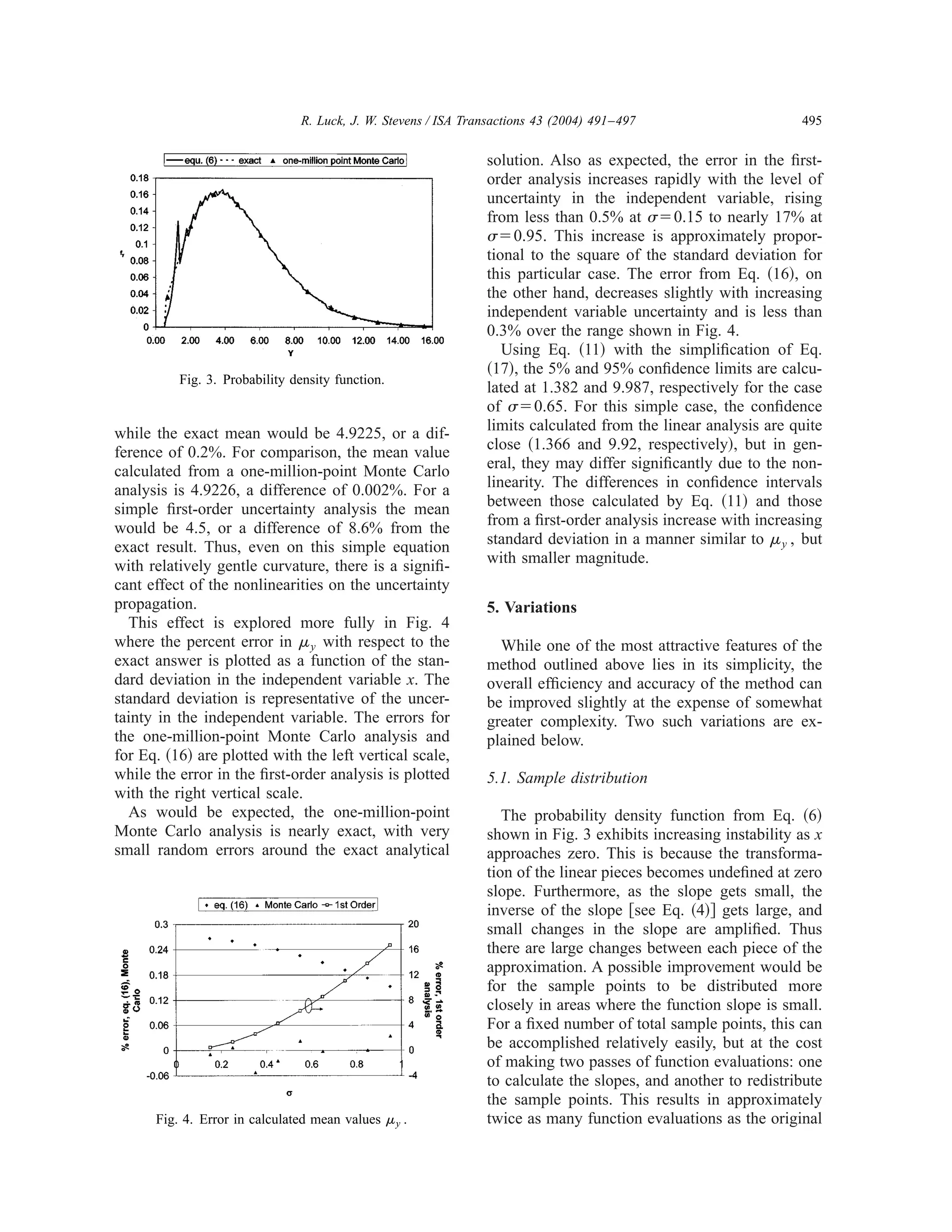

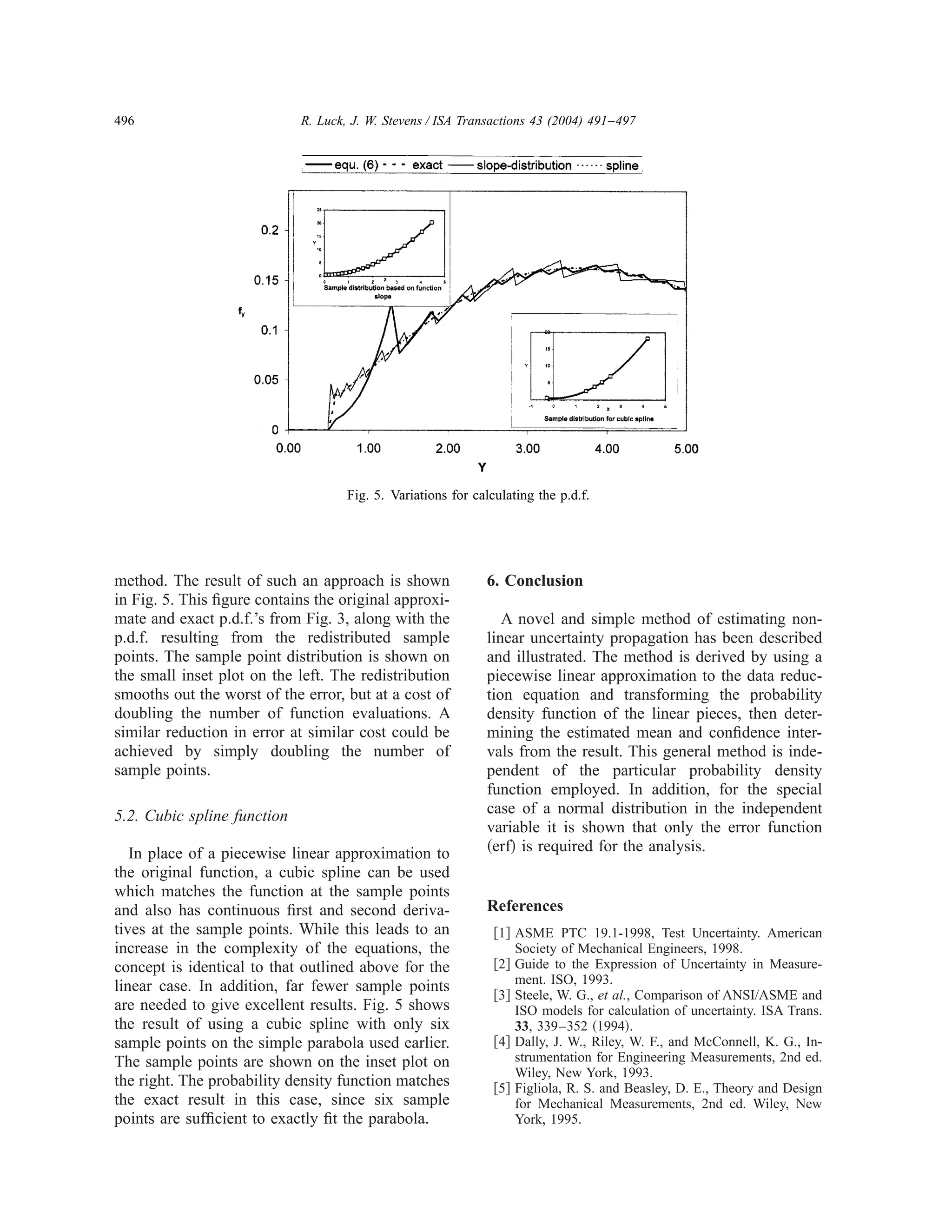

This document presents a numerical method for estimating nonlinear uncertainty propagation. The method approximates the nonlinear function with piecewise linear segments. It then calculates the probability density function of the dependent variable based on the transformations of the linear segments. For functions of a normally distributed independent variable, the mean and confidence intervals of the dependent variable can be calculated using only the error function. A simple example of applying this method to a parabolic function is presented to demonstrate the technique.