This document discusses the significance of psychological testing in employment contexts, highlighting how tests are used to assess job candidates' qualifications and predict their job performance. It emphasizes the importance of test validity and reliability to ensure fair and effective evaluation processes, noting the potential legal implications of poorly designed tests. Additionally, it addresses the growing trend of integrating various assessment methods within organizations for selection, promotion, and training purposes.

![Applicants’ Reactions to Tests

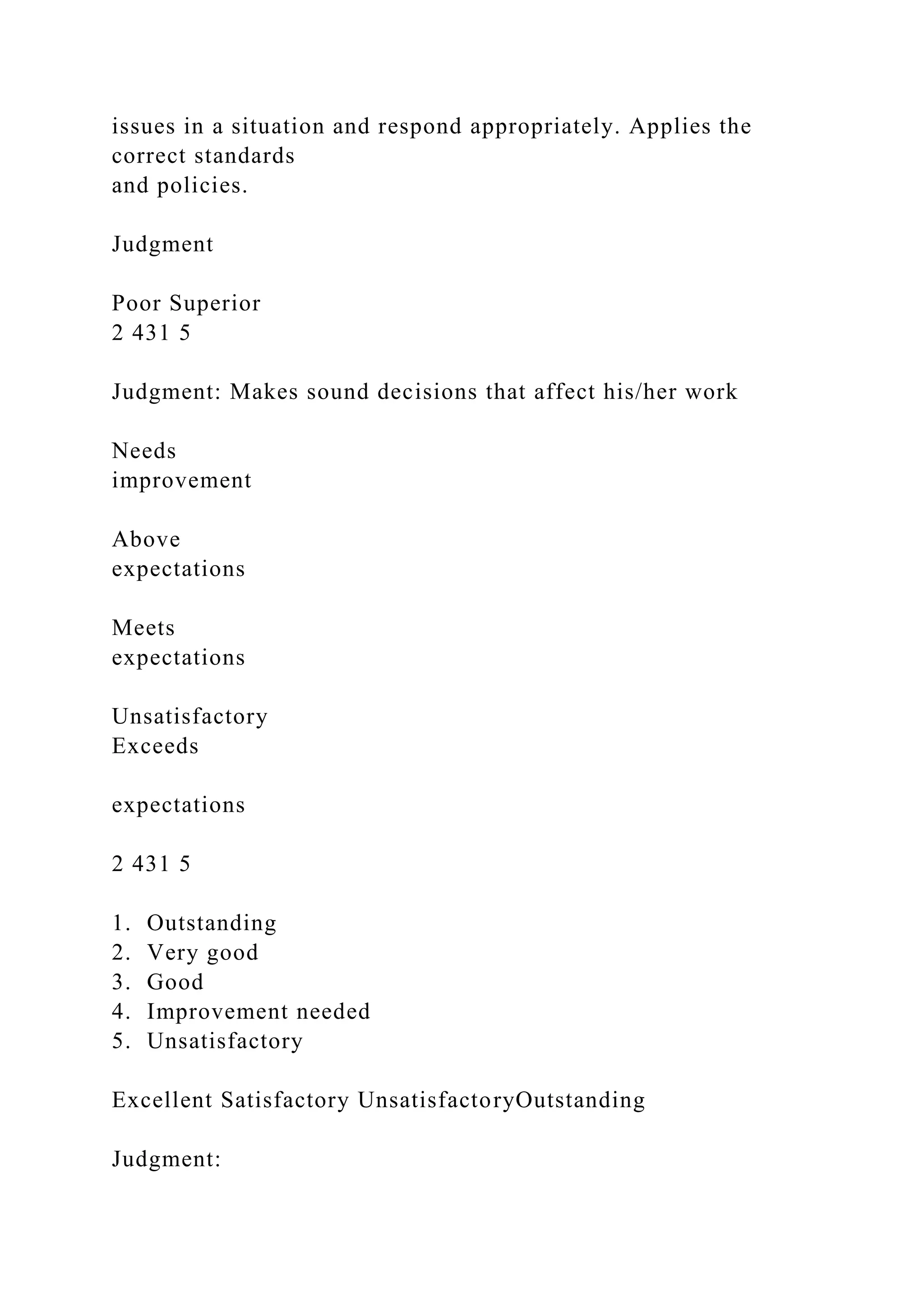

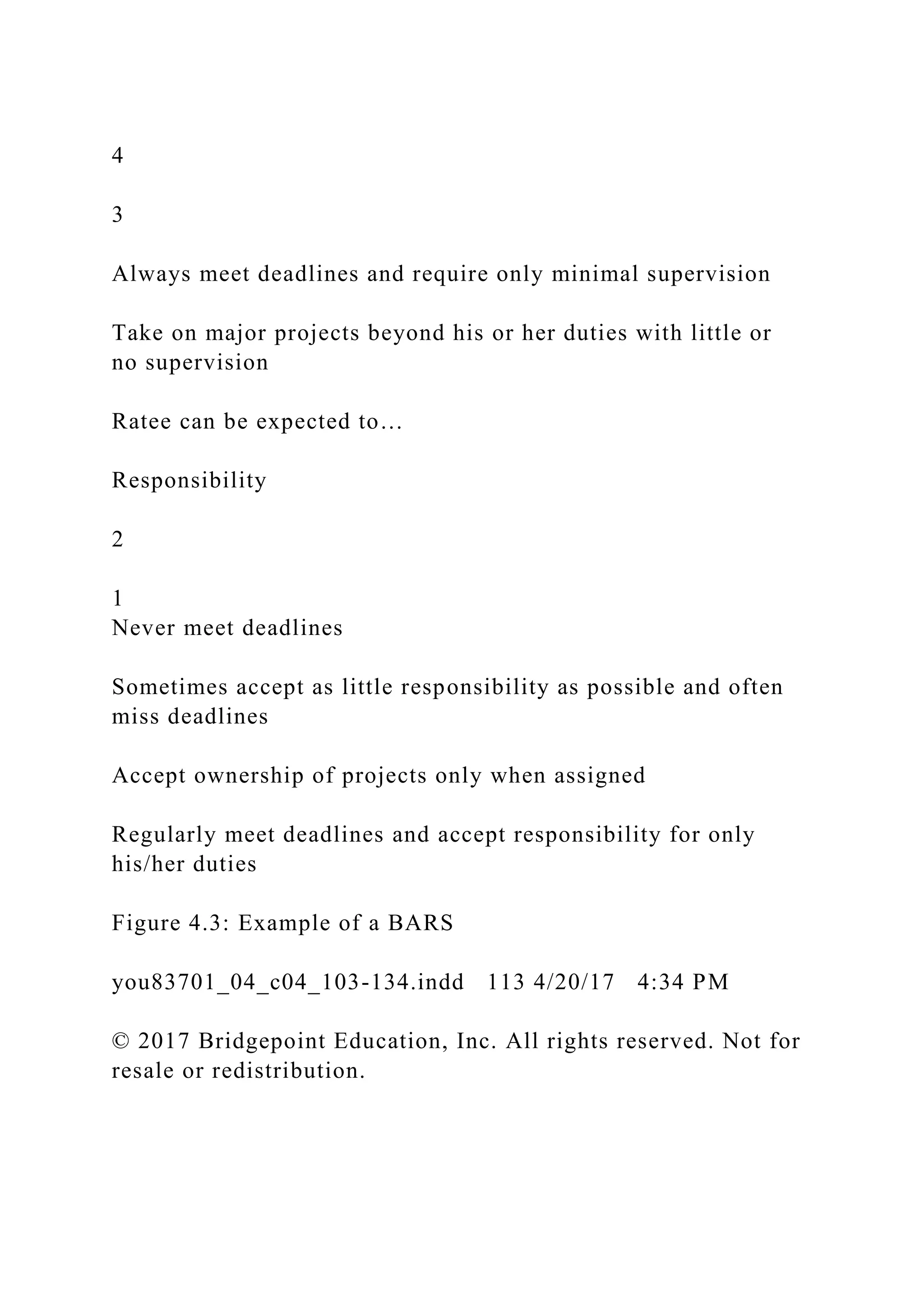

Most research about testing has focused on technical aspects—

content, type, statistical mea-

sures, scoring, and interpretation—and not on social aspects.

The fact is, no matter how use-

ful and important tests are, applicants generally do not like

taking them. According to a study

by Schmit and Ryan (1997), 1 out of 3 Americans have a

negative perception of employment

testing. Another study found that students, after completing a

number of different selection

measures as part of a simulated application process, preferred

hiring processes that excluded

testing (Rosse, Ringer, & Miller, 1996). Additional research has

shown that applicants’ nega-

tive perceptions about tests significantly affect their opinions

about the organization giving

the test. It is important for I/O psychologists to understand how

and why this occurs so they

can adopt testing procedures that are more agreeable to test

takers and that reflect a more

positive organizational image.

Typically, negative reactions to tests lower applicants’

perceptions of several organizational

outcome variables, including organizational attraction (how

much they like a company), job

acceptance intentions (whether they will accept a job offer),

recommendation intentions

(whether they will tell others to patronize or apply for a job at

the company), and purchasing

intentions (whether they will shop at or do business with the

company). A study conducted

in 2006 found that “[e]mployment tests provide organizations

with a serious dilemma [: . . .]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/673foundationsofpsychologicaltestingnoelhendrick-221108012202-58ccfef5/75/673Foundations-of-Psychological-TestingNoel-Hendrick-docx-74-2048.jpg)

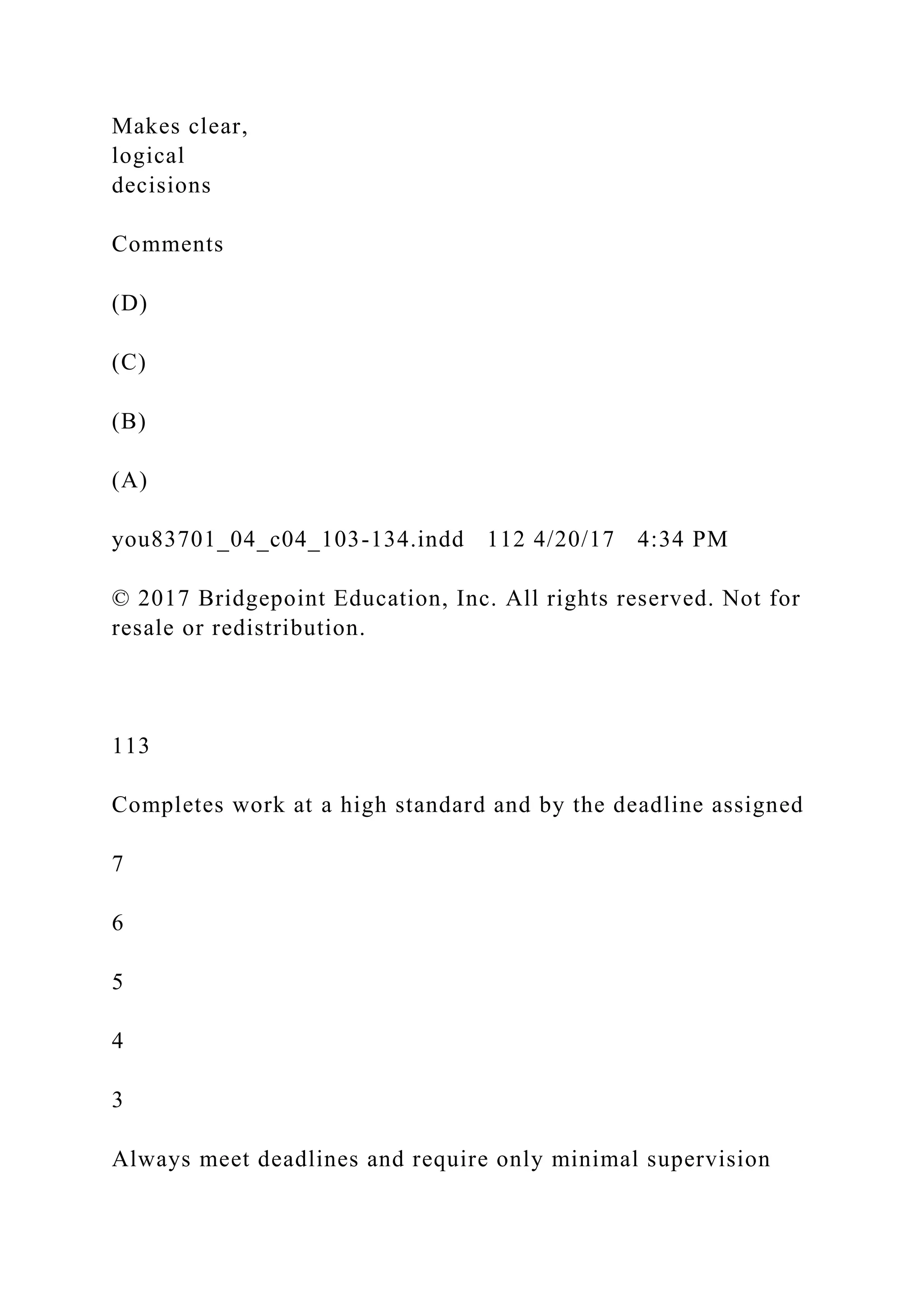

![how can [they] administer assessments in order to take

advantage of their predictive capa-

bilities without offending the applicants they are trying to

attract?” (Noon, 2006, p. 2). With

the increasing war for top-quality talent, organizations must

develop recruitment and selec-

tion tools that attract, rather than drive away, highly qualified

personnel.

What Can Be Done?

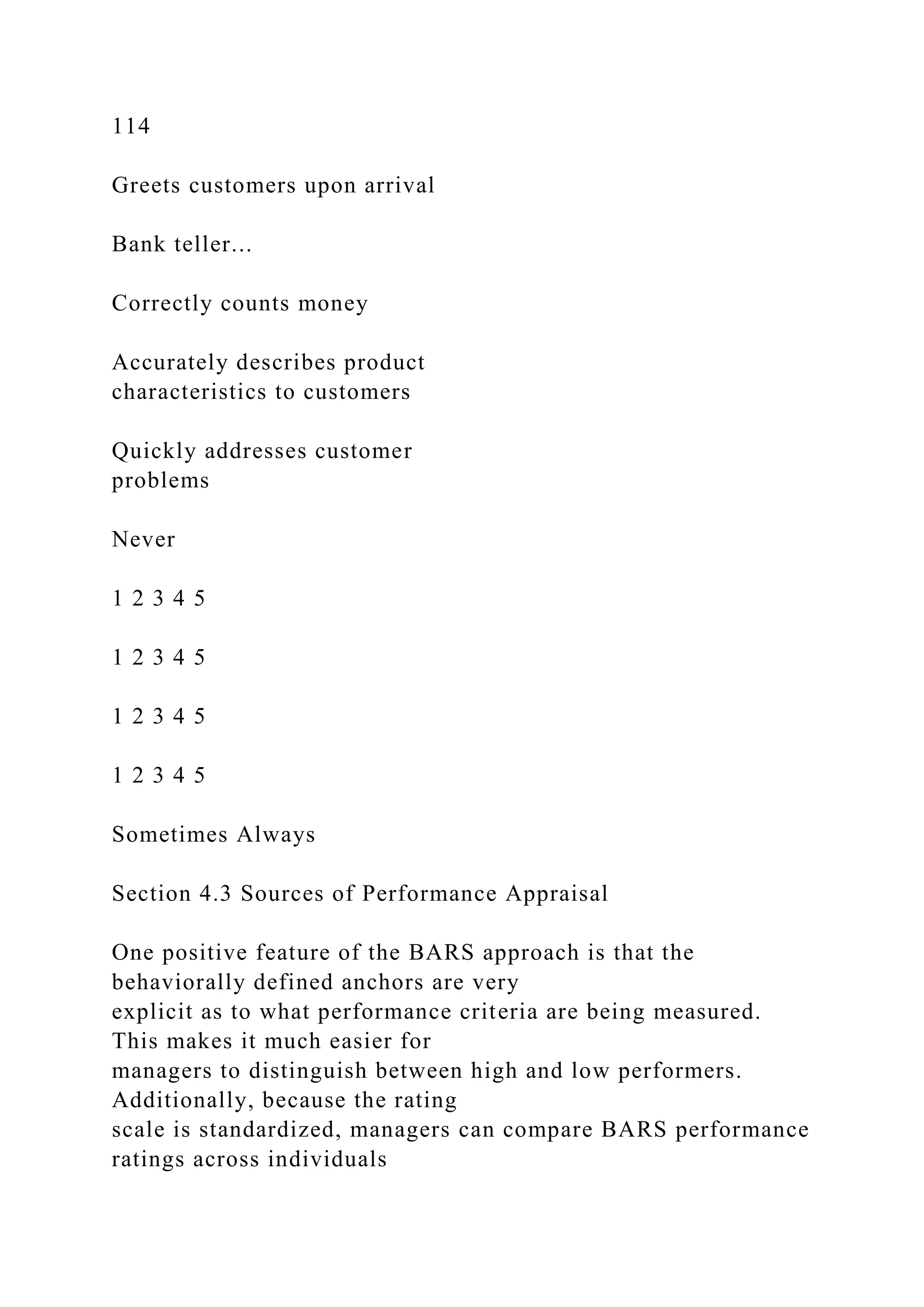

I/O psychologists have addressed this dilemma by identifying

several ways to improve testing

perceptions. One is to increase the test’s face validity. For

example, applicants typically view

cognitive ability tests negatively, but their reactions change if

the test items are rewritten

to reflect a business-situation perspective. Similarly,

organizations can use test formats that

already tend to be viewed positively, such as assessment centers

and work samples, because

they are easily relatable to the job (Smither et al., 1993).

Providing applicants with information about the test is another,

less costly way to improve

perceptions. Applicants can be told what a test is intended to

measure, why it is necessary,

who will see the results, and how these will be used (Ployhart &

Hayes, 2003). Doing so should

lead applicants to view both the organization and its treatment

of them during the selection

process more favorably (Gilliland, 1993). Noon’s 2006 study

investigated applicants’ reac-

tions to completing cognitive ability and personality tests as

part of the selection process for

a data-processing position. Half of the applicants received

detailed information explaining](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/673foundationsofpsychologicaltestingnoelhendrick-221108012202-58ccfef5/75/673Foundations-of-Psychological-TestingNoel-Hendrick-docx-75-2048.jpg)

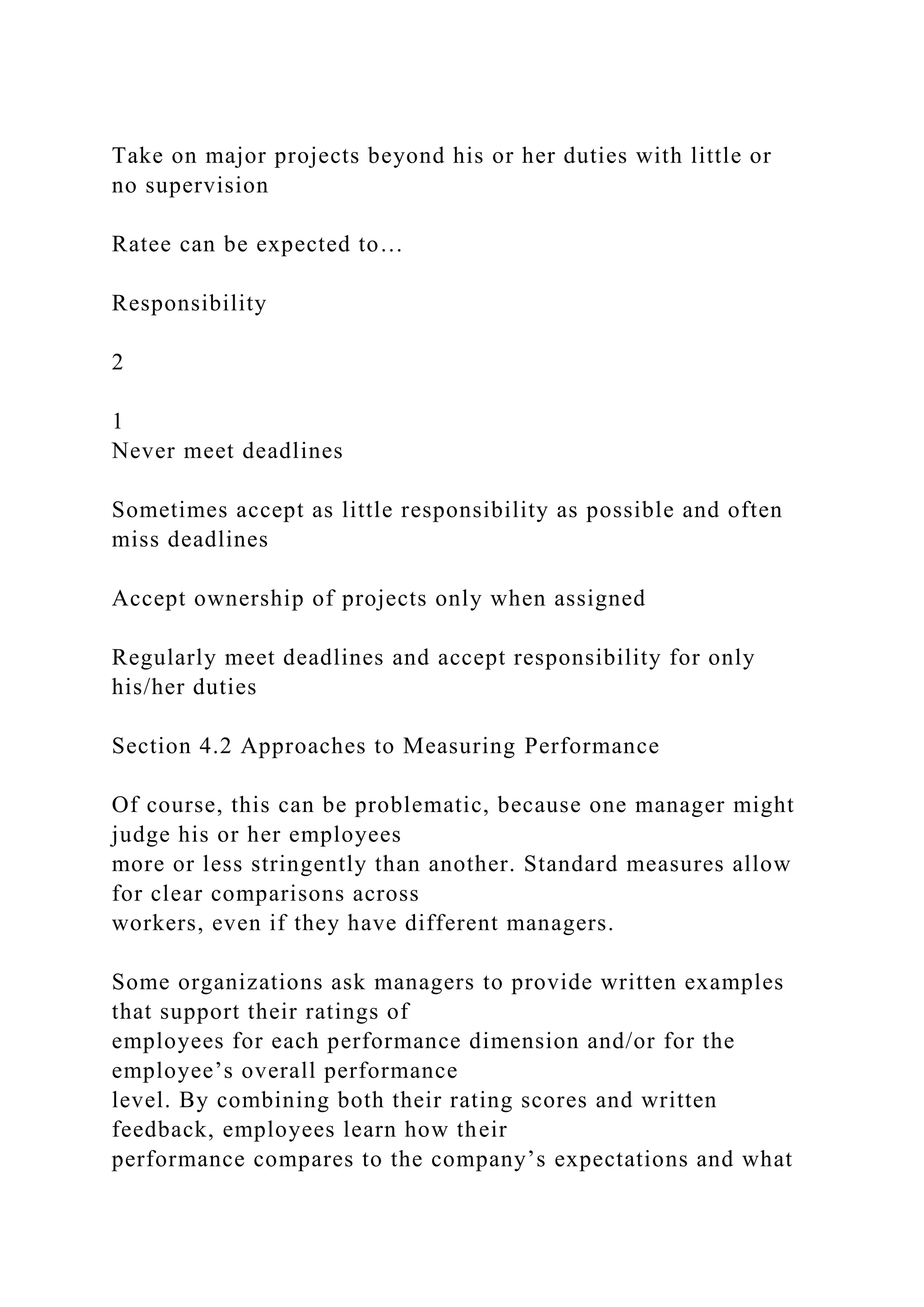

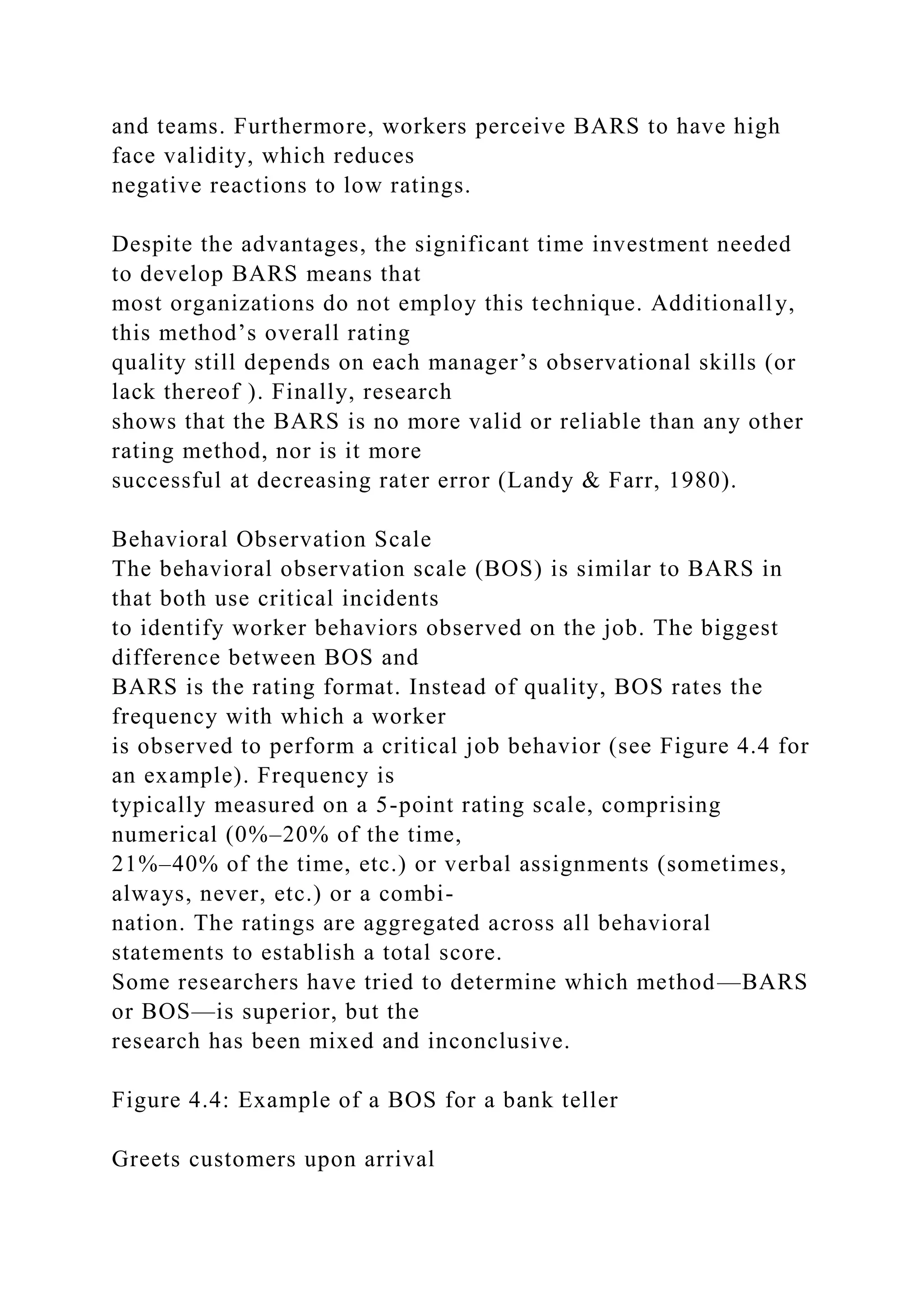

![Paired Comparison

As with rank ordering, the paired comparison technique requires

the manager to evaluate

a worker’s performance compared to the other workers on the

team. In a systematic fashion,

the manager compares one pair of workers at a time and then

judges which of the two dem-

onstrates superior performance. After comparing all the workers

in all possible pairings, the

manager then creates a rank ordering based on the number of

times each worker is the better

performer of a pair. For example, using the formula N(N -

1)/2)]N to determine the number

of discrete pairings in a group, a manager with 10 employees

would need to make 45 paired

comparisons. A manager with a team of 20 employees would

need to make 190 comparisons.

As you can see, the number of pairs goes up quite quickly as the

size of the team increases. For

this reason, paired comparisons are only advantageous for

smaller groups.

Like general rank orderings, paired comparisons do not provide

performance feedback. How-

ever, they are generally simpler to use because managers need

only compare one employee

pair at a time, instead of the entire work team. Organizational

leaders should keep in mind

that rankings are not standard across the entire workplace. The

lowest ranked member of a

high-performing team might, for example, actually perform

better than the highest ranked

member of a poorly performing team.

Forced Distribution

When an organization needs to evaluate a large number of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/673foundationsofpsychologicaltestingnoelhendrick-221108012202-58ccfef5/75/673Foundations-of-Psychological-TestingNoel-Hendrick-docx-103-2048.jpg)

![resale or redistribution.

Multimedia

Dimoff, D. (Producer). (2011). Performance evaluation (Links

to an external site.)Links to an external site. [Video segment].

In D. S. Walko, & B. Kloza (Executive Producers), Managing

your business: Prices, finances, and staffing. Retrieved from

https://fod.infobase.com/OnDemandEmbed.aspx?token=42251&

wID=100753&loid=116118&plt=FOD&w=420&h=315

· The full version of this video is available through the Films

On Demand database in the Ashford University Library. This

video discusses the role of performance reviews, and provides

guidance. This video has closed captioning. It may assist you in

your discussions, Assessment in the Workplace Diversity and

the Organizational Process, this week.

Accessibility Statement (Links to an external site.)Links to an

external site.

Privacy Policy

Marofsky, M., Grote, K. (Writers), Christiansen, L., Dean, W.

(Directors), Christiansen, L., & Hommeyer, T (Producers).

(1991). Understanding our biases and assumptions (Links to an

external site.)Links to an external site. [Video file]. Retrieved

from

https://fod.infobase.com/OnDemandEmbed.aspx?token=2574&w

ID=100753&plt=FOD&loid=0&w=640&h=480&fWidth=660&f

Height=530

· The full version of this video is available through the Films

On Demand database in the Ashford University Library. This

video discusses the nature of biases and preconceptions, and it

stresses the need to examine one’s own thinking about “us” and

“them.” This video has closed captioning. It may assist you in

your discussions, Assessment in the Workplace Diversity and

the Organizational Process, this week.

Accessibility Statement (Links to an external site.)Links to an](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/673foundationsofpsychologicaltestingnoelhendrick-221108012202-58ccfef5/75/673Foundations-of-Psychological-TestingNoel-Hendrick-docx-166-2048.jpg)

![external site.

Privacy Policy (Links to an external site.)Links to an external

site.

Preparing for my appraisal: Cutting edge communication

comedy series (Links to an external site.)Links to an external

site. [Video file]. (2016). Retrieved from

https://fod.infobase.com/OnDemandEmbed.aspx?token=111702

&wID=100753&plt=FOD&loid=0&w=640&h=360&fWidth=660

&fHeight=410

· The full version of this video is available through the Films

On Demand database in the Ashford University Library. This

video shows several examples of different work appraisals,

showing the “dos” and “don’ts” and providing helpful tips. This

video has closed captioning. It may assist you in your

discussions, Assessment in the Workplace Diversity and the

Organizational Process, this week.

Accessibility Statement (Links to an external site.)Links to an

external site.

Privacy Policy (Links to an external site.)Links to an external

site.

Twitter: Login (Links to an external site.)Links to an external

site. (2017). Retrieved from https://twitter.com/login

Accessibility Statement (Links to an external site.)Links to an

external site.

Privacy Policy (Links to an external site.)Links to an external

site.

Twitter Support (Links to an external site.)Links to an external

site.(2017). Retrieved from

https://support.twitter.com/articles/215585#

Accessibility Statement (Links to an external site.)Links to an

external site.

Privacy Policy (Links to an external site.)Links to an external

site.

What your boss wants: Business (Links to an external

site.)Links to an external site. [Video file]. (2013). Retrieved

from](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/673foundationsofpsychologicaltestingnoelhendrick-221108012202-58ccfef5/75/673Foundations-of-Psychological-TestingNoel-Hendrick-docx-167-2048.jpg)

![https://fod.infobase.com/OnDemandEmbed.aspx?token=94142&

wID=100753&plt=FOD&loid=0&w=640&h=360&fWidth=660&

fHeight=410

· The full version of this video is available through the Films

On Demand database in the Ashford University Library. This

video gives an insider’s perspective on what makes a good job

application, a successful interview, what to expect in the

induction process, and the types of assessments at the end of the

probationary period. This video has closed captioning. It may

assist you in your discussions, Assessment in the Workplace

Diversity and the Organizational Process, this week.

Accessibility Statement (Links to an external site.)Links to an

external site.

Privacy Policy (Links to an external site.)Links to an external

site.

Supplemental Material

Rosser-Majors, M. (2017). Week Two Study Guide. Ashford

University.

Recommended Resource

Multimedia

Bandura, A., Jordan, D. S. (Writers), & Davidson, F. W.

(Producer). (2003). Modeling and observational learning – 4

processes [Video segment]. In Bandura’s social cognitive

theory: An introduction. Retrieved from

https://fod.infobase.com/OnDemandEmbed.aspx?token=44898&

wID=100753&loid=114202&plt=FOD&w=420&h=315&fWidth=

440&fHeight=365

· The full version of this video is available through the Films

On Demand database in the Ashford University Library. In this

video, Albert Bandura explains the four processes of

observational learning. He also describes the Bobo doll

experiment on the social modeling of aggression. This video has

closed captioning. It may assist you in your discussions,

Assessment in the Workplace Diversity and the Organizational

Process, this week.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/673foundationsofpsychologicaltestingnoelhendrick-221108012202-58ccfef5/75/673Foundations-of-Psychological-TestingNoel-Hendrick-docx-168-2048.jpg)