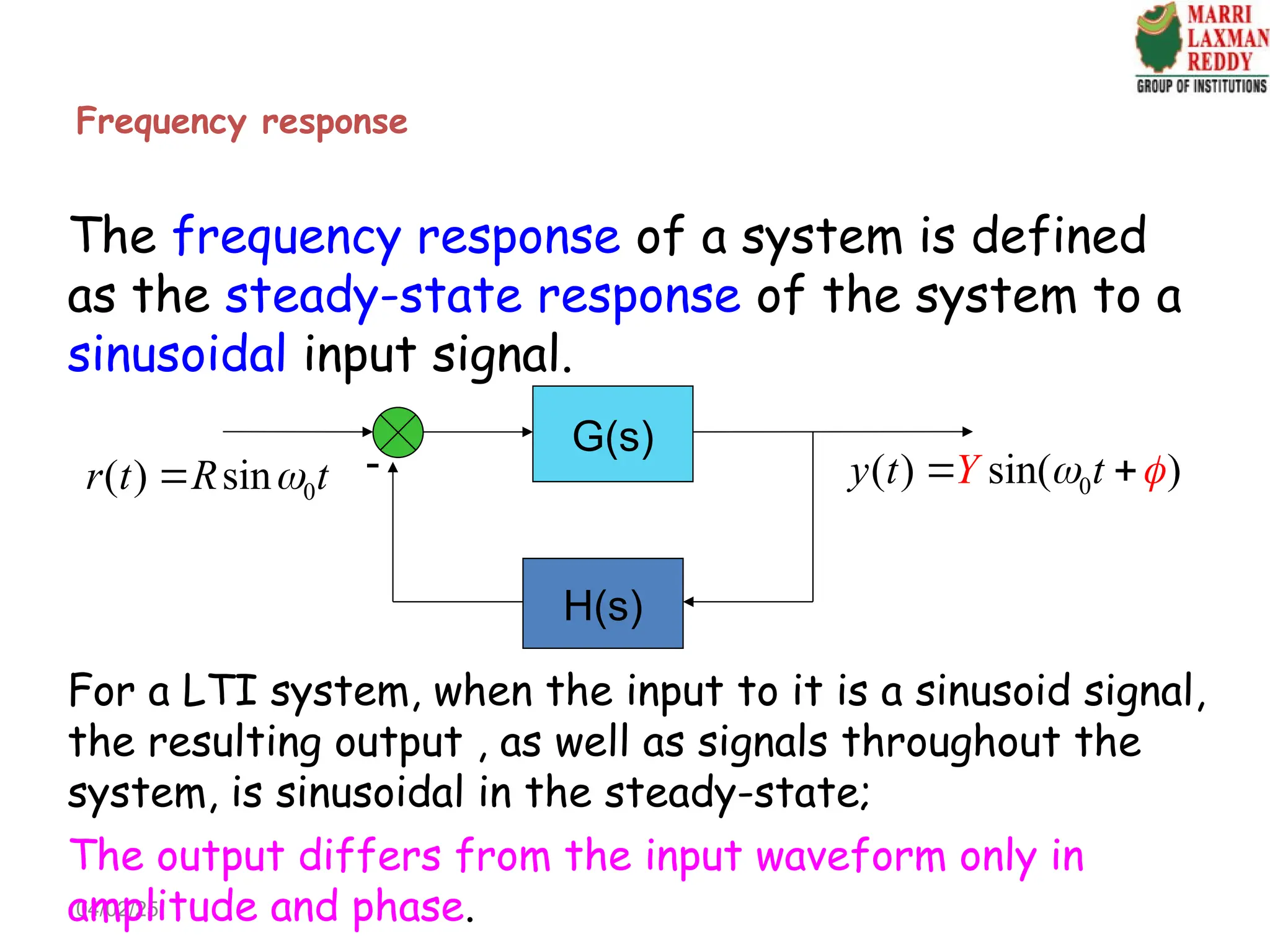

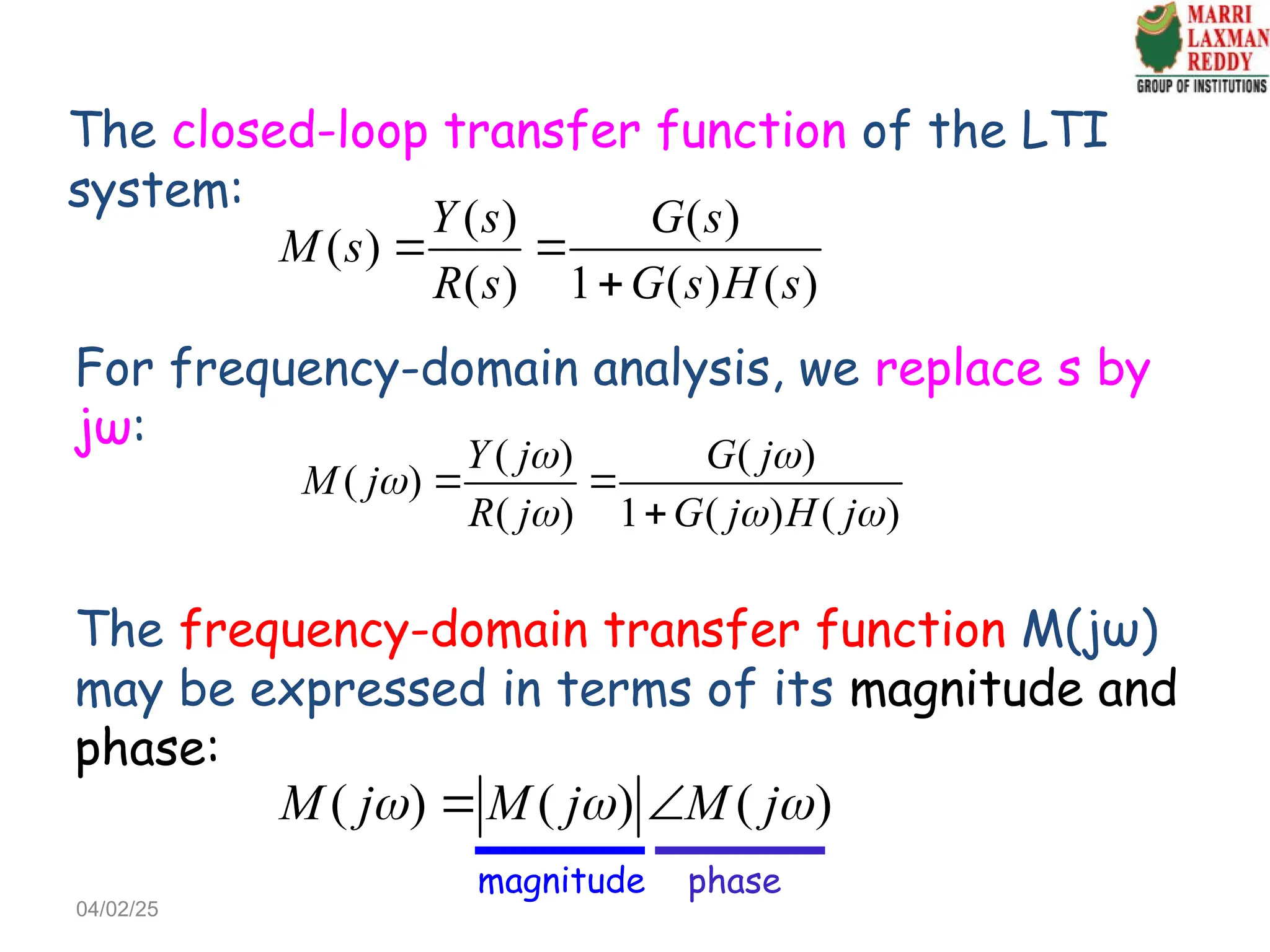

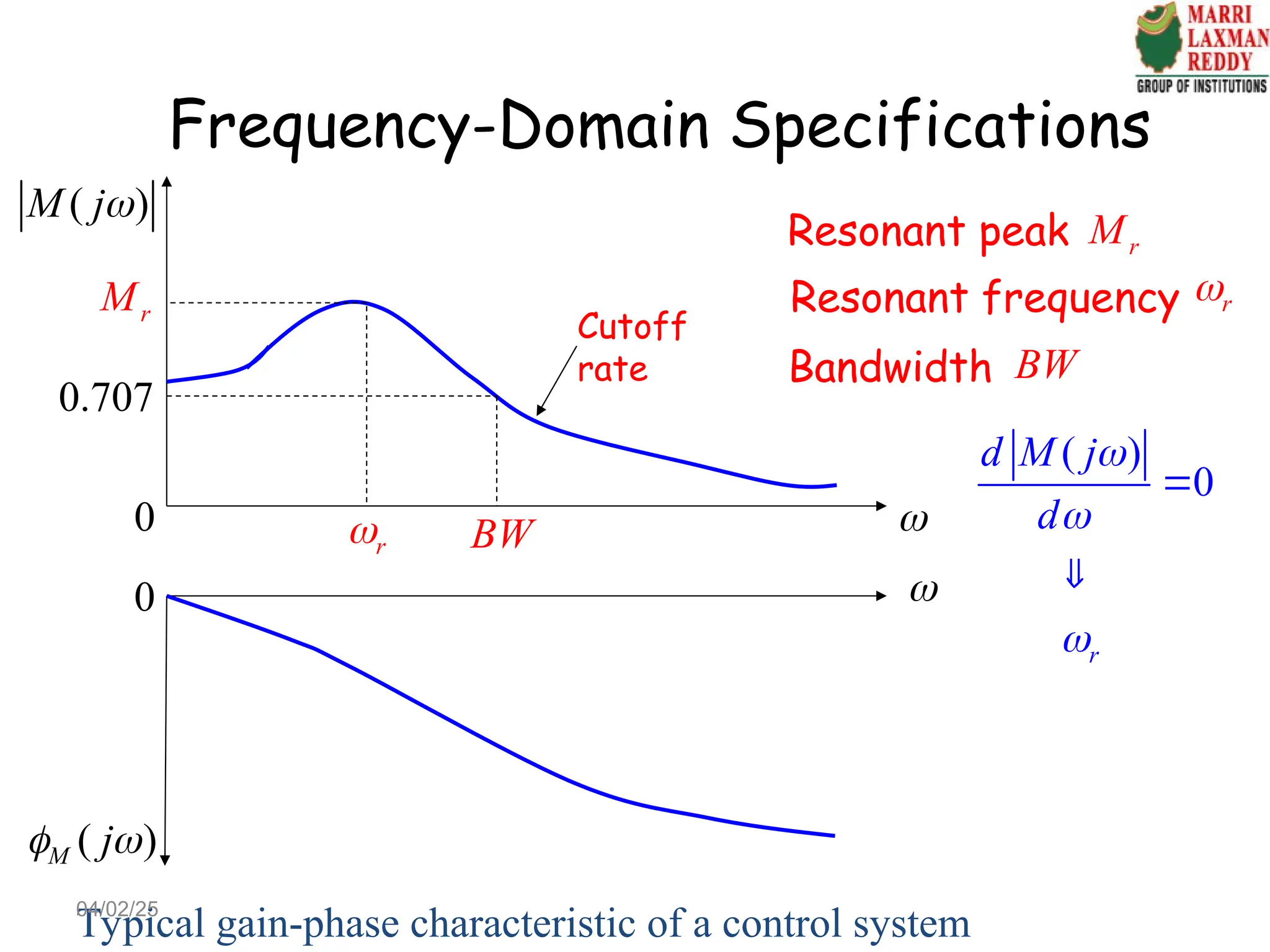

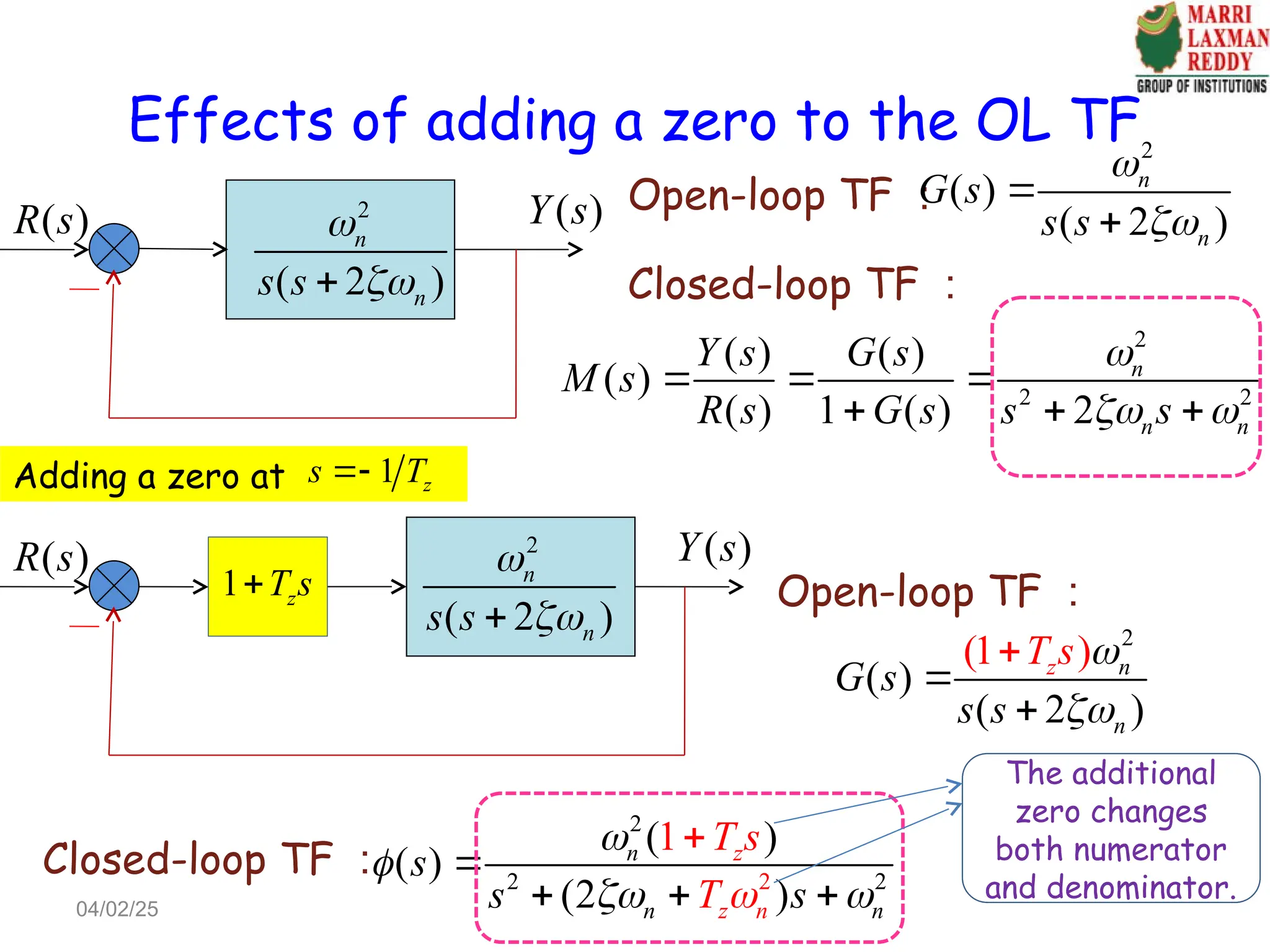

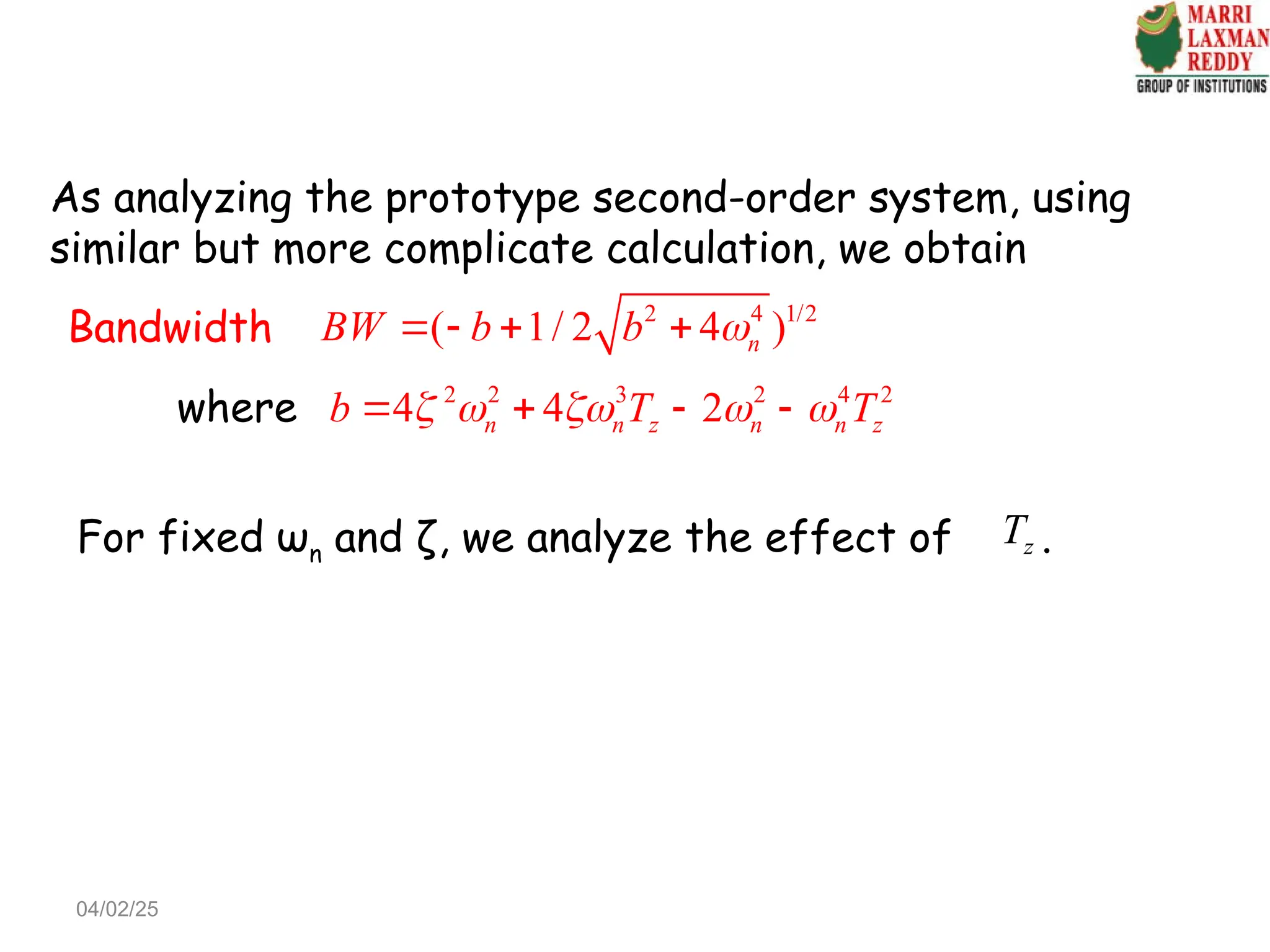

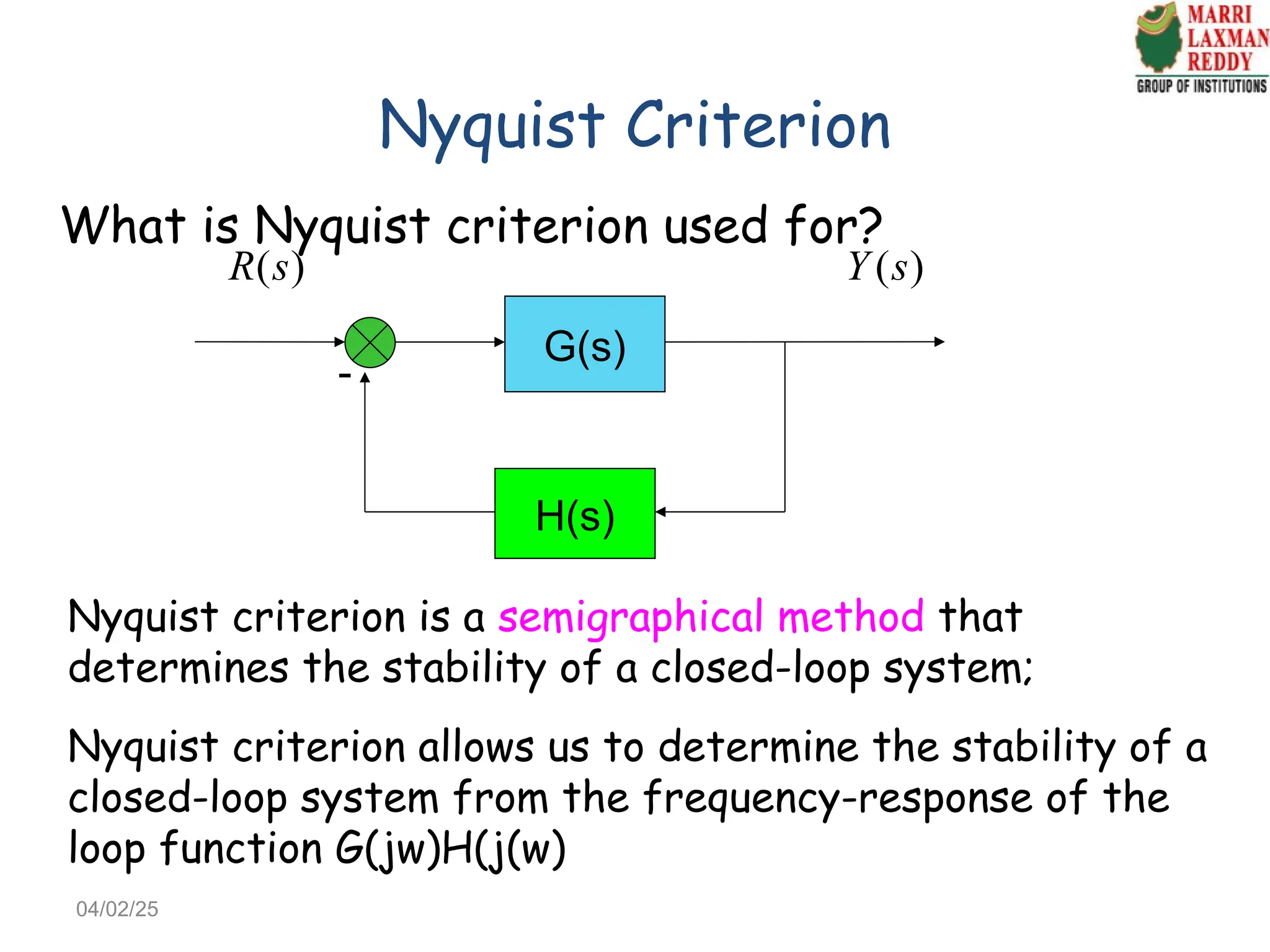

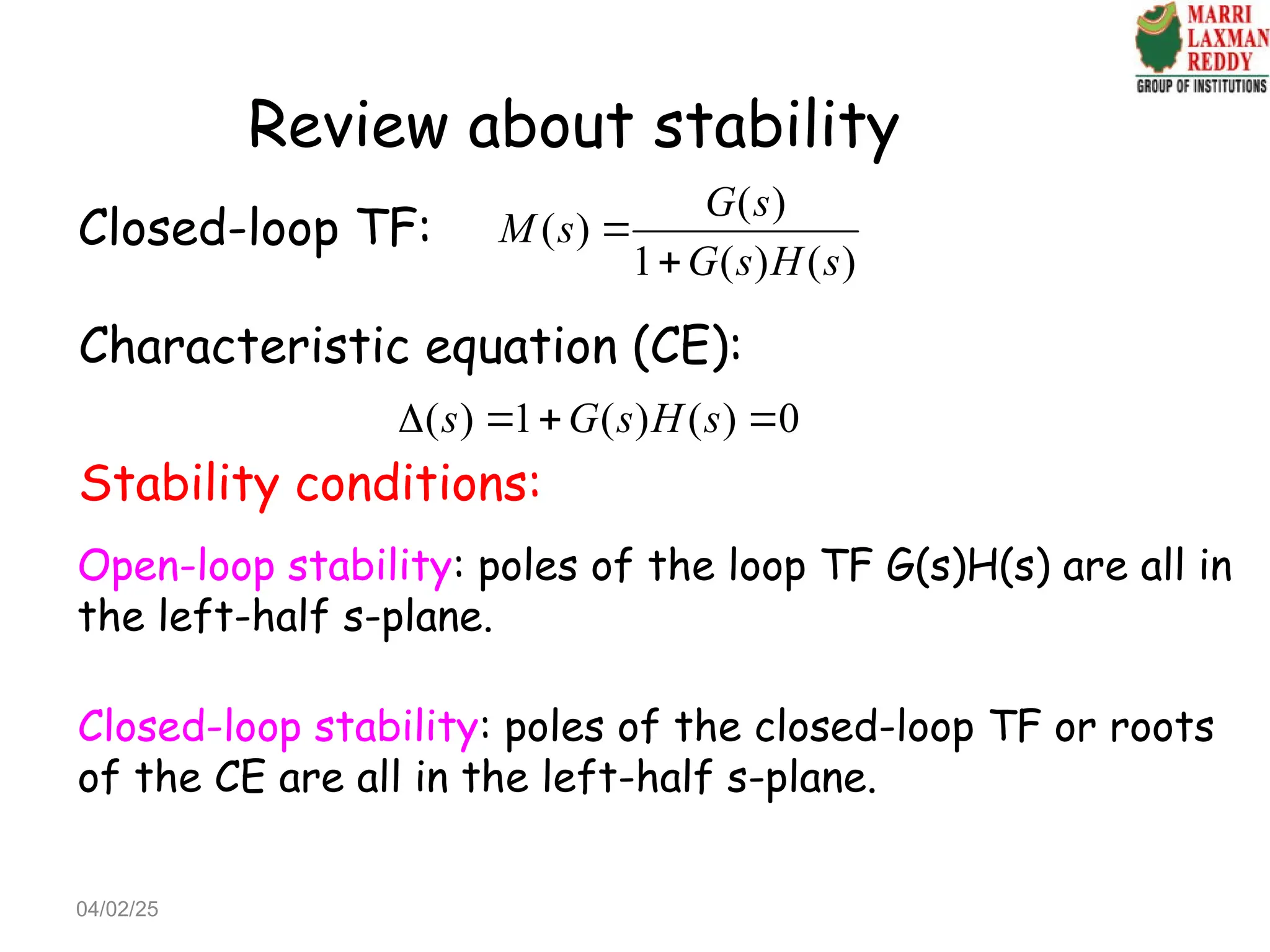

Chapter 4 discusses frequency-domain analysis, focusing on frequency response and its significance in feedback control system design. The chapter outlines the advantages of using frequency-response methods, including the ability to work with uncertain plant models and utilize experimental data for design without complex data processing. It also covers key concepts such as transfer functions, gain-phase characteristics, and the Nyquist criterion for determining stability in closed-loop systems.

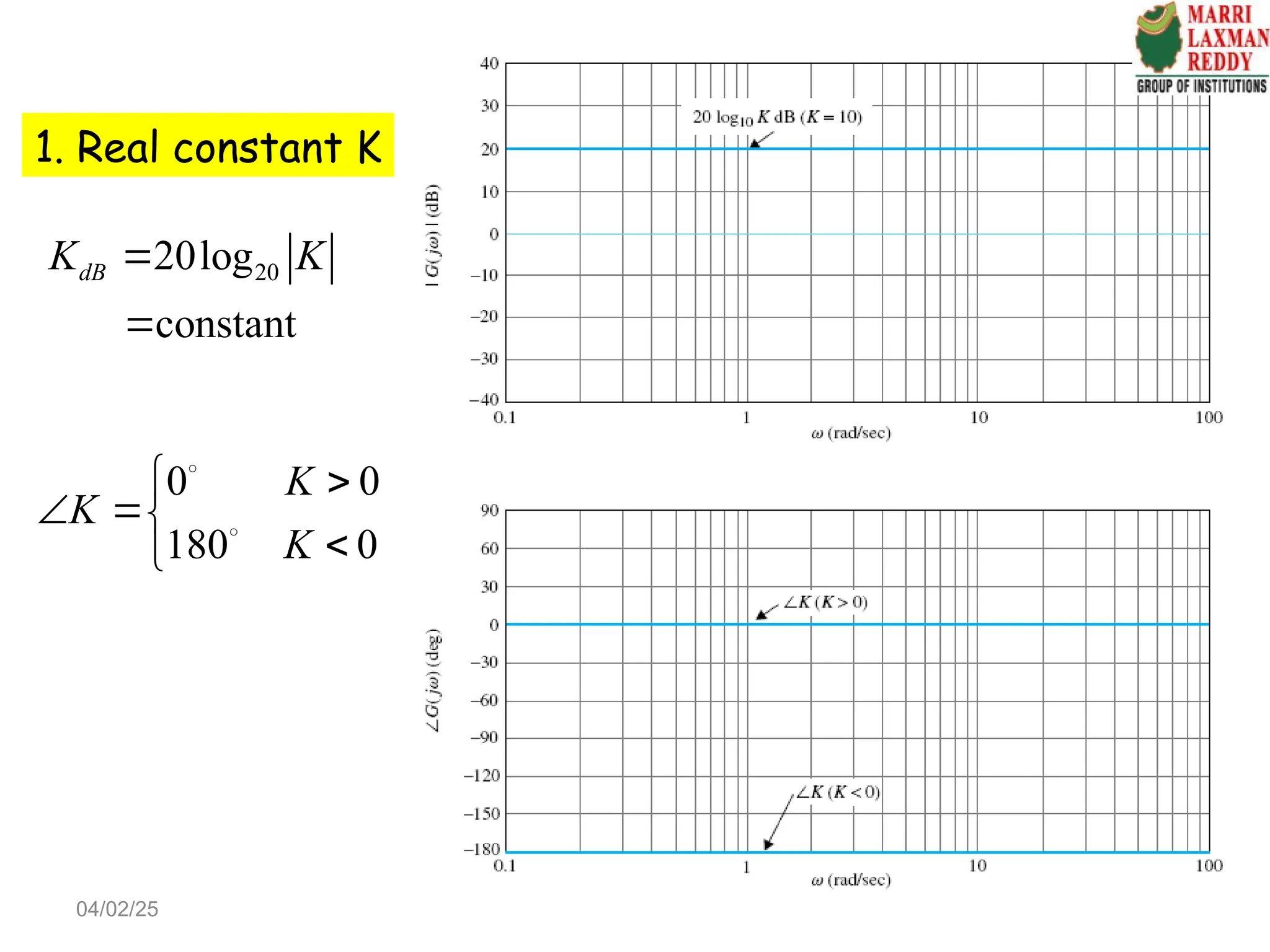

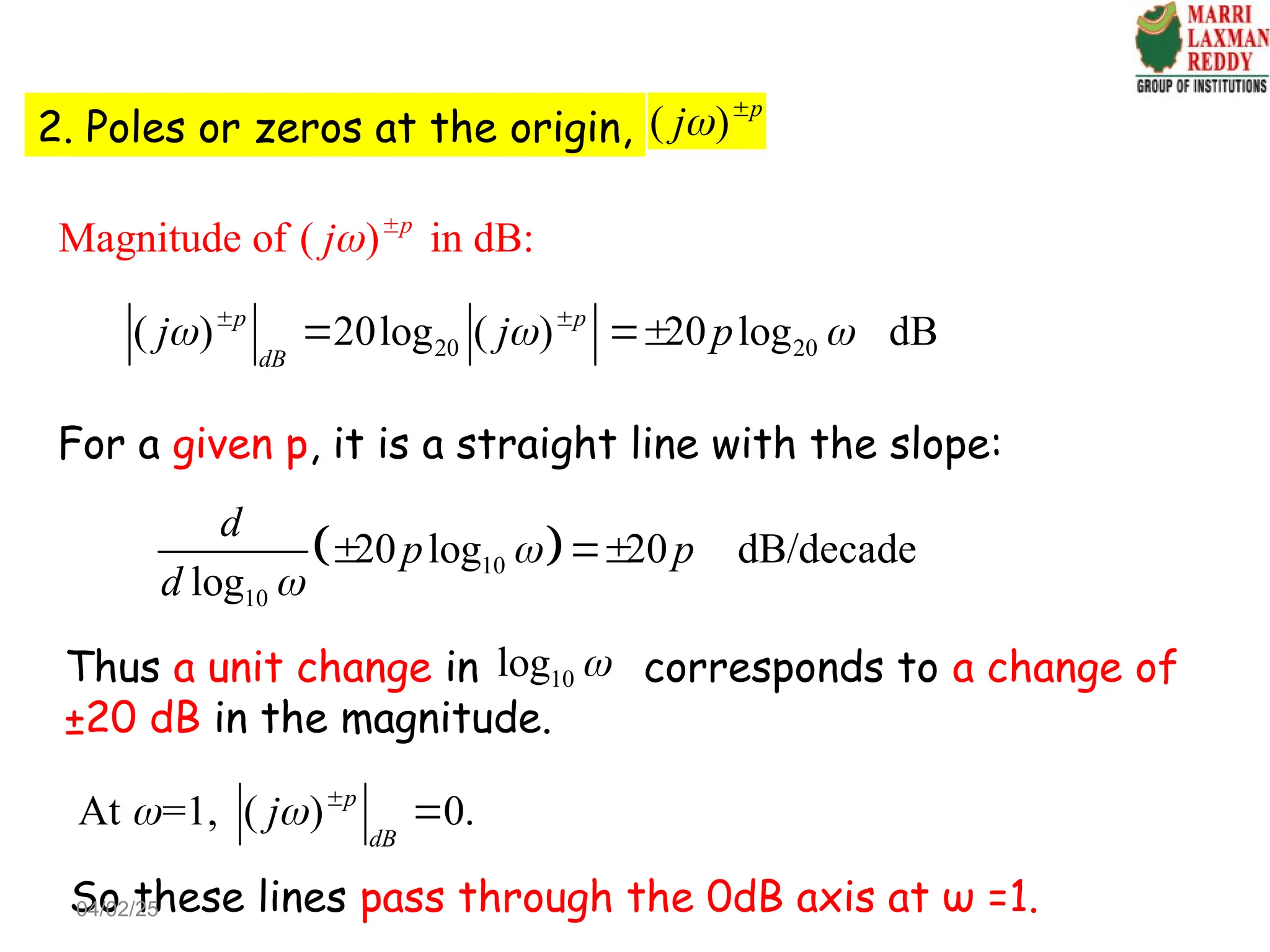

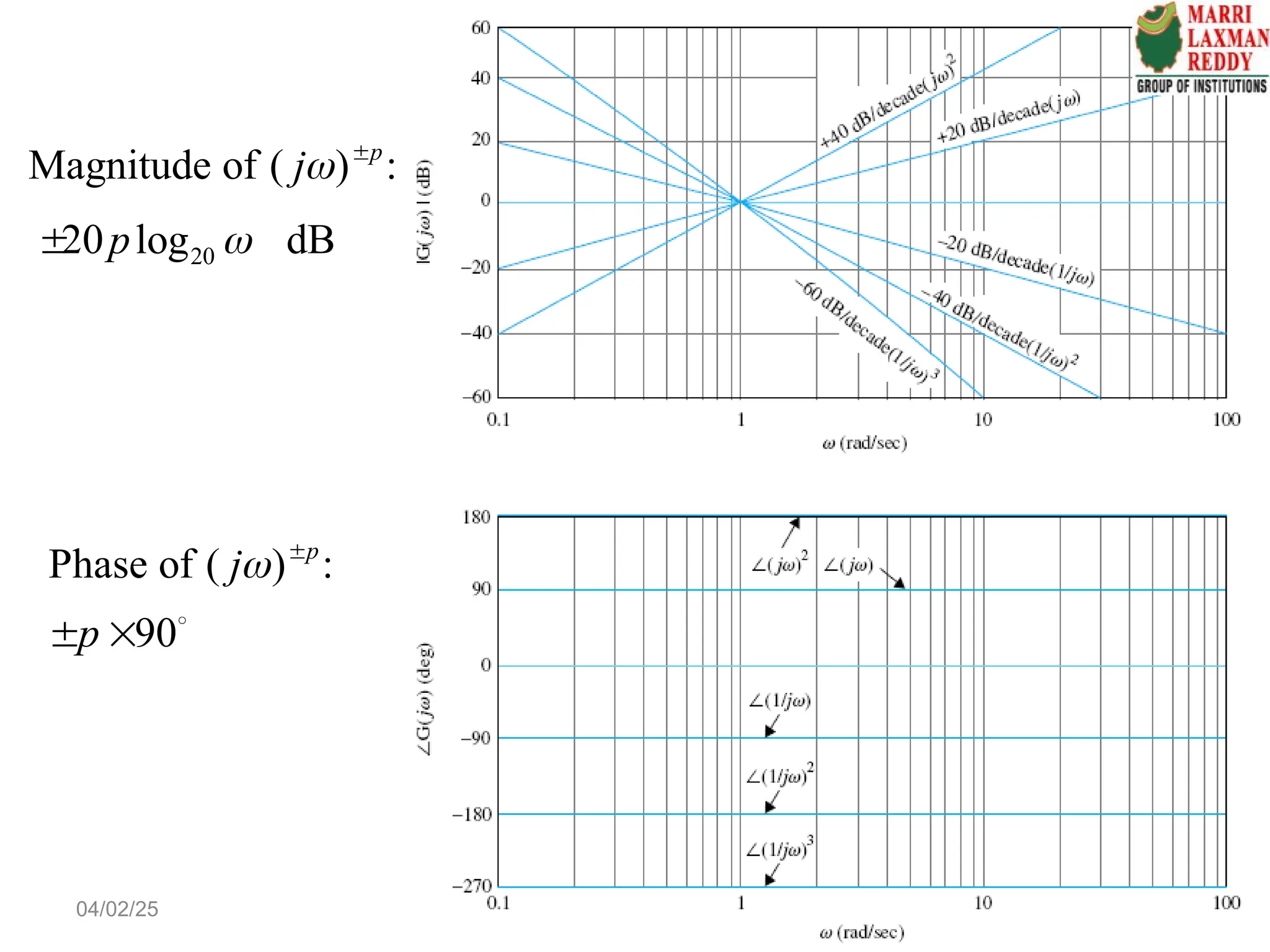

![The magnitude of M(ju) is

2 2 2 1/2

1

( )

[(1 ) (2 ) ]

M ju

u u

The phase of M(ju) is

1

2

2

( ) ( ) tan

1

M

u

M j j

u

The resonant frequency of M(ju) is

( )

0

d M ju

du

2

1 2

r

u

With , we have

r r n

u

2

1 2

r n

Since frequency is a real quantity, it requires 2

1 2 0

So 0.707

2

1

2 1

r

M

Resonant peak

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-12-2048.jpg)

![According to the definition of Bandwidth

2 2 2 1/2

1 1

( ) 0.707

[(1 ) (2 ) ] 2

M ju

u u

2 2 4 2

(1 2 ) 4 4 2

u

With , we have

n

u

2 4 2 1/2

[(1 2 ) 4 4 2]

n

BW

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-13-2048.jpg)

![Resonant peak

2

1

2 1

r

M

Resonant frequency

2

1 2

r n

For a prototype second-order system ( )

0.707

Bandwidth

2 4 2 1/2

[(1 2 ) 4 4 2]

n

BW

depends on only.

For 0, the system is unstable;

For 0< 0.707, ;

For 0.707, 1

r

r

r

M

M

M

depends on both and .

For 0< 0.707, fixed, ;

For 0.707, 0.

r n

n r

r

is directly proportional to ,

For 0 0.707, fixed, ;

n n

n

n

BW BW

BW

BW

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-14-2048.jpg)

![Correlation between pole locations, unit-step response and

the magnitude of the frequency response

2

2 2

2

n

n n

s s

( )

r t ( )

y t

0 1

j

0

n

1

cos

0

( )

M j

0dB

0.3dB

BW

2 4 2 1/2

[(1 2 ) 4 4 2]

n

BW

2

1 0.4167 2.917

r

n

t

0

( )

y t

1.0

0.9

0.1 t

2

/ 1

max overshoot e

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-15-2048.jpg)

![Resonant peak

2

(

1

2 1

0.707)

r

M

0.6

18

n

For 0< 0.707, ;

For 0.707, 1

r

r

M

M

1 1.04

r

M

0.6

Bandwidth

2 4 2 1/2

[(1 2 ) 4 4 2]

n

BW

is directly proportional to ,

For 0 0.707, fixed, ;

n n

n

n

BW BW

BW

BW

0.6 0.707

1 1.15

n

BW

1.15

n n

BW

18

n

18

BW

Based on time-domain analysis, we obtain and

Frequency-domain specifications:

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-17-2048.jpg)

![Mapping from the complex s-plane to the

Δ(s) -plane

Exercise 1: Consider a function Δ(s) =s-1, please map a

circle with a radius 1 centered at 1 from s-plane to the

Δ(s)-plane .

1 2

3 4

2; 1

0; 1

s s j

s s j

1 2

3 4

( ) 1; ( )

( ) 1; ( )

s s j

s s j

Δ( s)-plane

Im

j

Re[ ( )]

s

1

( )

s

2

( )

s

3

( )

s

4

( )

s

0

1

s-plane

j

1

s

2

s

3

s

4

s

2

1

1

0

Mapping

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-28-2048.jpg)

![-2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

Nyquist Diagram

Real Axis

Imaginary

Axis

An example

Consider the system with

the loop function

3

5

( ) ( )

( 1)

G s H s

s

Matlab program for

Nyquist plot

(G(s)H(s) plot)

>>num=5;

>>den=[1 3 3 1];

>>nyquist(num,den);

Question 1: is the

closed-loop system

stable?

Question 2: what if

3

5

( ) ( ) ?

( 1)

K

G s H s

s

N=0, P=0,

N=-P, stable

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-35-2048.jpg)

![Root Locus

Real Axis

Imaginary

Axis

-4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

*

3 3

5 1

( ) ( )

( 1) ( 1)

K

G s H s K

s s

1. With root locus technique:

For K* varies from 0

to ∞, we draw the RL

>>num=1;

>>den=[1 3 3 1];

>>rlocus(num,den);

When K*=8

(K=1.6), the RL

cross the jw-axis,

the closed-loop

system is

marginally stable.

For K*>8 (K>1.6), the closed-loop system has two roots in

the RHP and is unstable.

*

K

*

K

*

K

*

0

K

*

8

K

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-36-2048.jpg)

![2. With Nyquist plot and

Nyquist criterion:

-2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

Nyquist Diagram

Real Axis

Imaginary

Axis

>>K=1;

>>num=5*K;

>>den=[1 3 3 1];

>>nyquist(num,den);

Nyquist plot

does not

encircle (-1,j0),

so N=0

K=1

3

5

( ) ( )

( 1)

K

G s H s

s

No pole of

G(s)H(s) in

RHP, so P=0;

Thus N=-P

The closed-loop system is stable

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-37-2048.jpg)

![-2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

Nyquist Diagram

Real Axis

Imaginary

Axis

2. With Nyquist plot and

Nyquist criterion:

>>K=1.6;

>>num=5*K;

>>den=[1 3 3 1];

>>nyquist(num,den);

The Nyquist plot

just go through

(-1,j0)

K=1.6

3

5

( ) ( )

( 1)

K

G s H s

s

No pole of

G(s)H(s) in RHP,

so P=0;

The closed-loop system is marginally stable

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-38-2048.jpg)

![-5 0 5 10 15 20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

Nyquist Diagram

Real Axis

Imaginary

Axis

2. With Nyquist plot and

Nyquist criterion:

>>K=4;

>>num=5*K;

>>den=[1 3 3 1];

>>nyquist(num,den);

Nyquist plot

encircles (-1,j0)

twice, so N=2

K=4

3

5

( ) ( )

( 1)

K

G s H s

s

No pole of

G(s)H(s) in RHP,

so P=0;

Thus Z=N+P=2

The closed-loop system has two poles in RHP and is unstable

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-39-2048.jpg)

![Example Consider a single-loop feedback system with the

loop transfer function

( ) ( ) ( )

( 2)( 10)

K

L s G s H s

s s s

Analyze the stability of the closed-loop system.

Solution.

Since L(s) is minimum-phase, we can analyze the closed-loop

stability by investigating whether the Nyquist plot enclose

the critical point (-1,j0) for L(jw)/K first.

( ) 1

( 2)( 10)

L j

K j j j

w=∞:

( )

0 270

L j

K

w=0+

:

( 0)

90

L j

K

0

Im

j

Real

0

Im[ ( ) ] 0

L j K

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-44-2048.jpg)

![1

Im[ ( ) ] Im[ ] 0

( 2)( 10)

L j K

j j j

20 /

rad s

The frequency is positive, so 20 /

rad s

1

( 20) 0.004167

20( 20 2)( 20 10)

L j K

j j j

1. 240 ( 20) 1

K L j

the Nyquist plot does not enclose (-1,jw);

2. 240 ( 20) 1

K L j

the Nyquist plot goes through (-1,jw);

3. 240 ( 20) 1

K L j

the Nyquist plot encloses (-1,jw).

stable

marginally stable

unstable

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-45-2048.jpg)

![-30 -25 -20 -15 -10 -5 0 5 10

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

Root Locus

Real Axis

Imaginary

Axis

1

( ) ( ) ( )

( 2)( 10)

L s G s H s K

s s s

>>z=[]

>>p=[0, -2, -10];

>>k=1

>>sys=zpk(z,p,k);

>>rlocus(sys);

240

K

By root locus technique

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-46-2048.jpg)

![If the Nyquist plot of G(jw) intersects with the real axis, we have

Im[ ( )] 0

G j

2

4 2 4 2

10 10 10

( )

( 1)

G j j

j j

4 2

10

0

This means that the G(jw) plot intersects only with the real axis of the

G(jw)-plane at the origin.

Similarly, intersection of G(jw) with the imaginary axis:

which corresponds to the origin of the G(jw)-plane.

The conclusion is that the Nyquist

plot of G(jw) does not intersect any

one of the axes at any finite

nonzero frequency.

Re[ ( )] 0

G j

At w=0, Re[ ( )] 10

G j

At w=∞, Re[ ( )] 0

G j

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-52-2048.jpg)

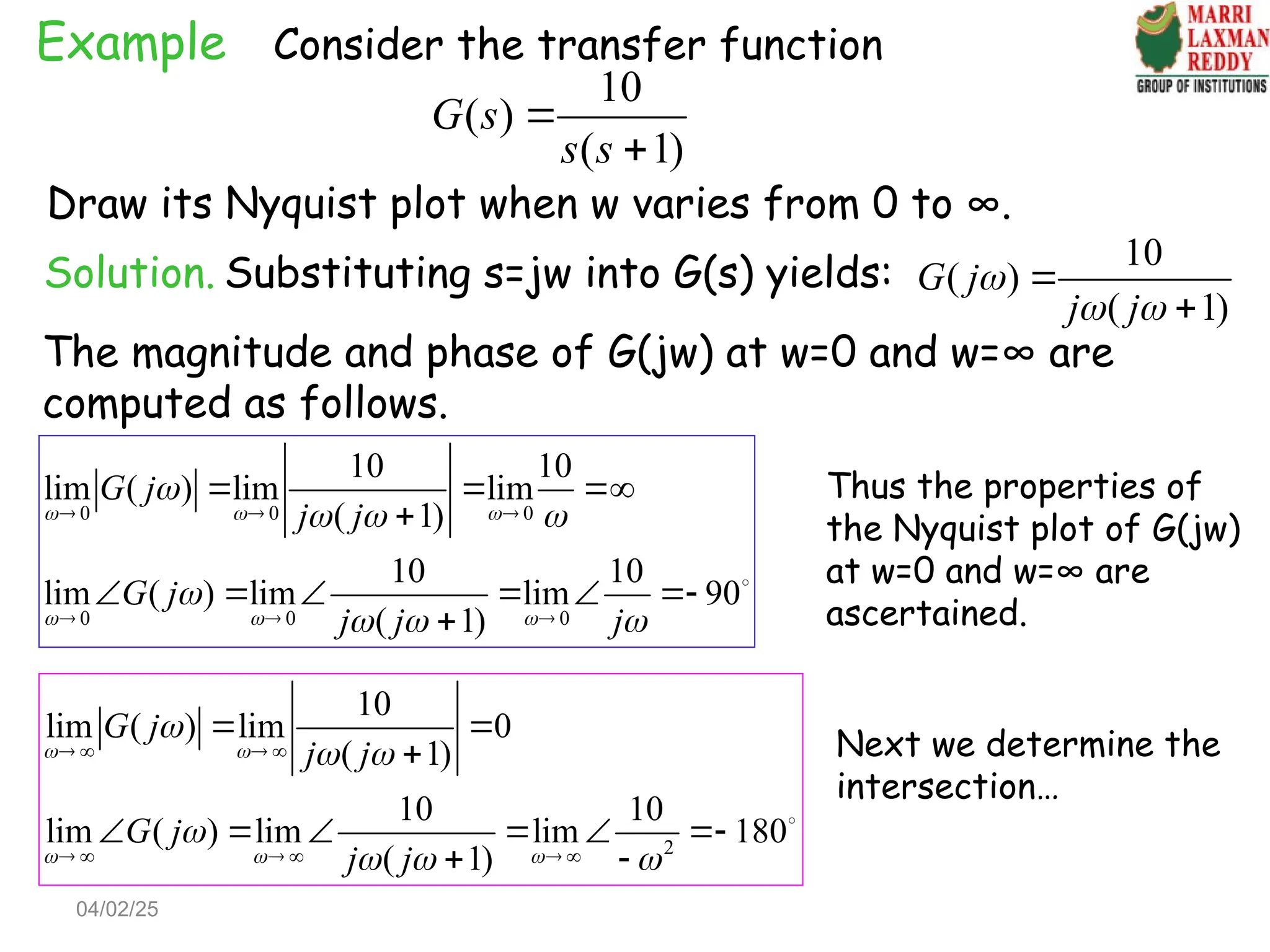

![Example Consider a system with a loop transfer function as

2500

( )

( 5)( 50)

L s

s s s

Determine its gain margin and phase margin.

Solution. Phase crossover frequency ωp:

Im[ ( )] 0 15.88 rad/sec

p

L j

10

GM = 20log ( ) 14.80 dB

p

L j

Gain margin:

Gain crossover frequency ωg:

( ) 1 6.22 rad/sec

g g

L j

Phase margin:

PM = ( ) 180 31.72

g

L j

0

Im

j

0

1

( ) 0.182

p

L j 15.88

p

6.22

g

31.72

0.182

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-53-2048.jpg)

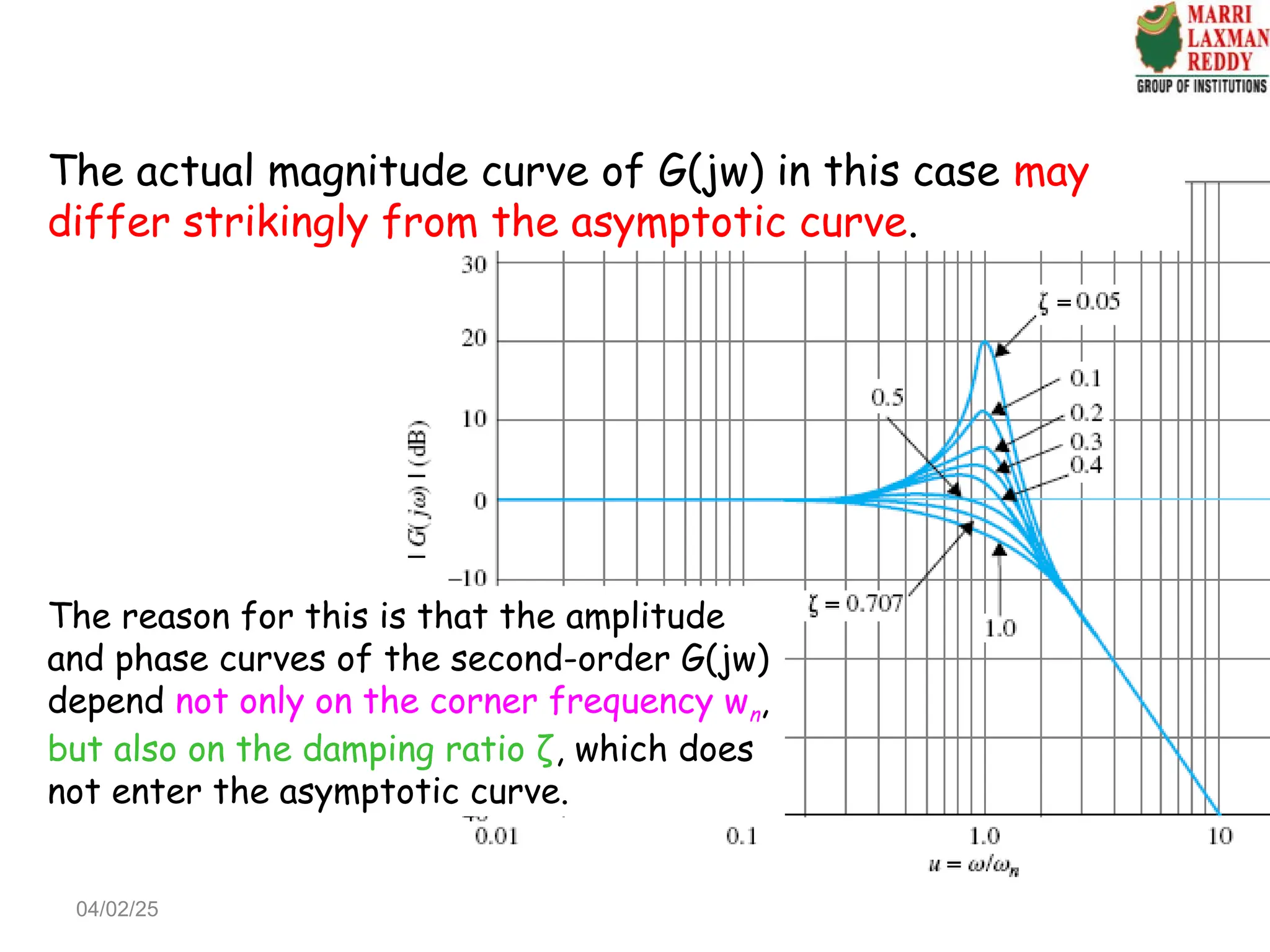

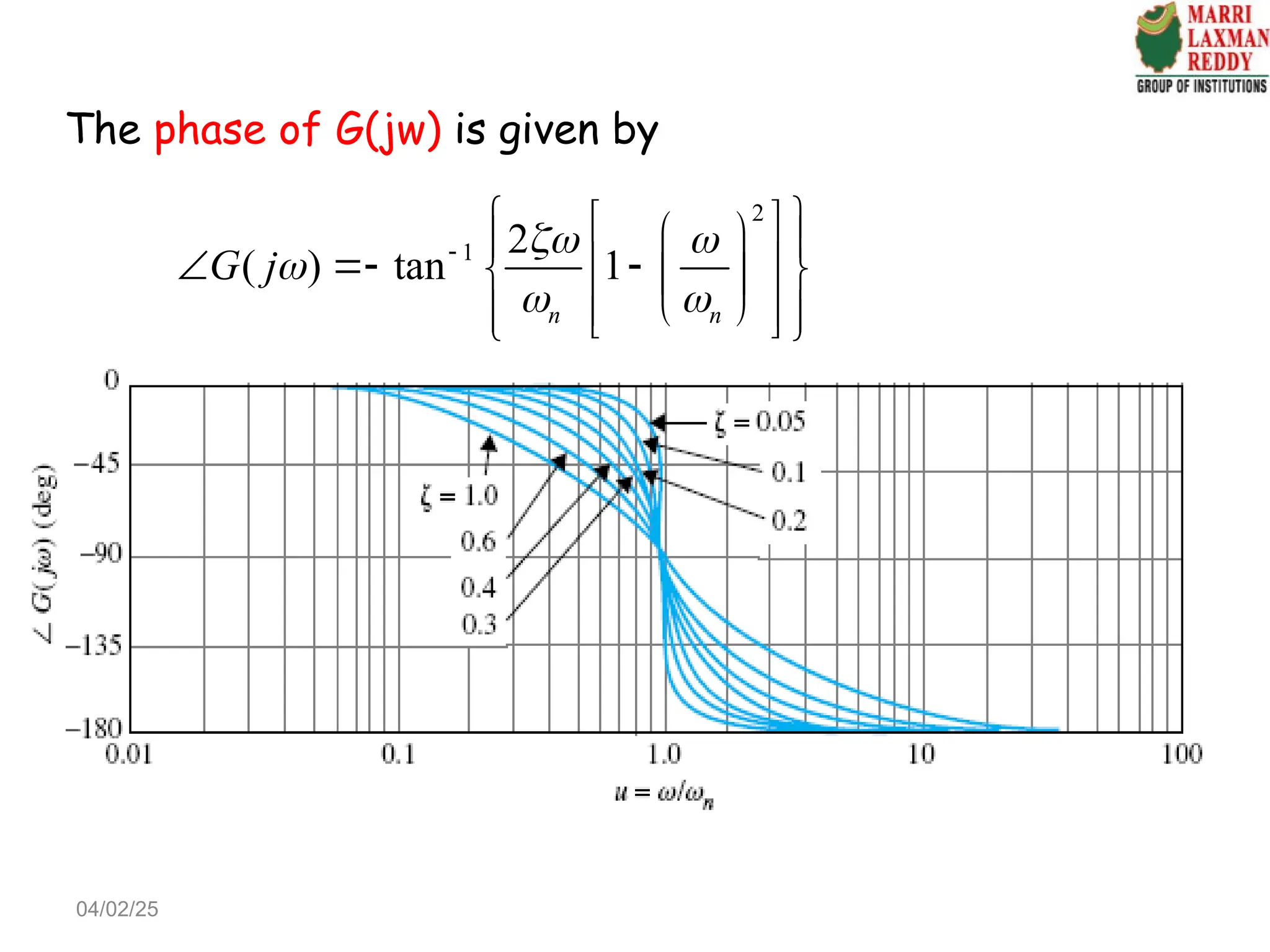

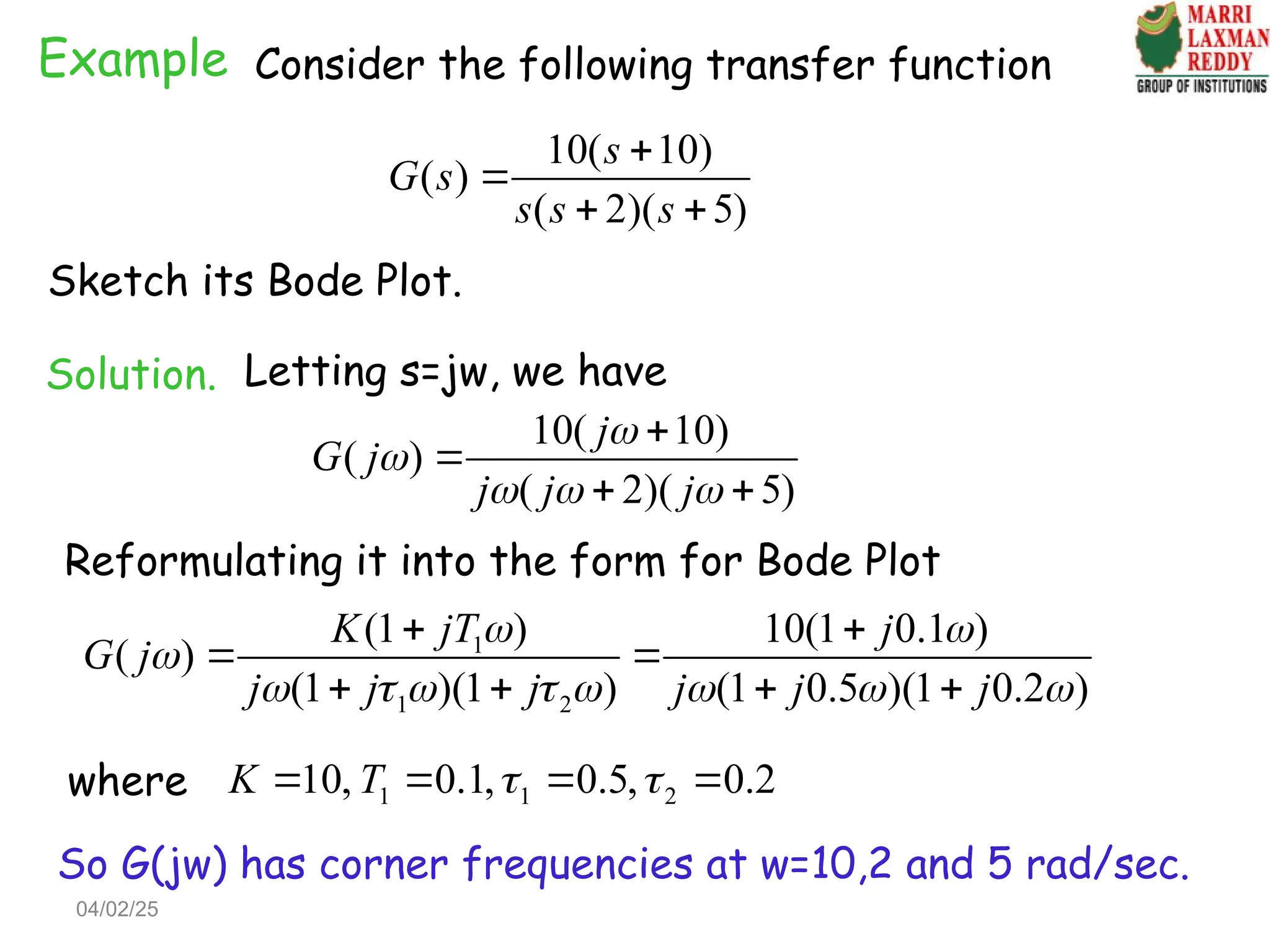

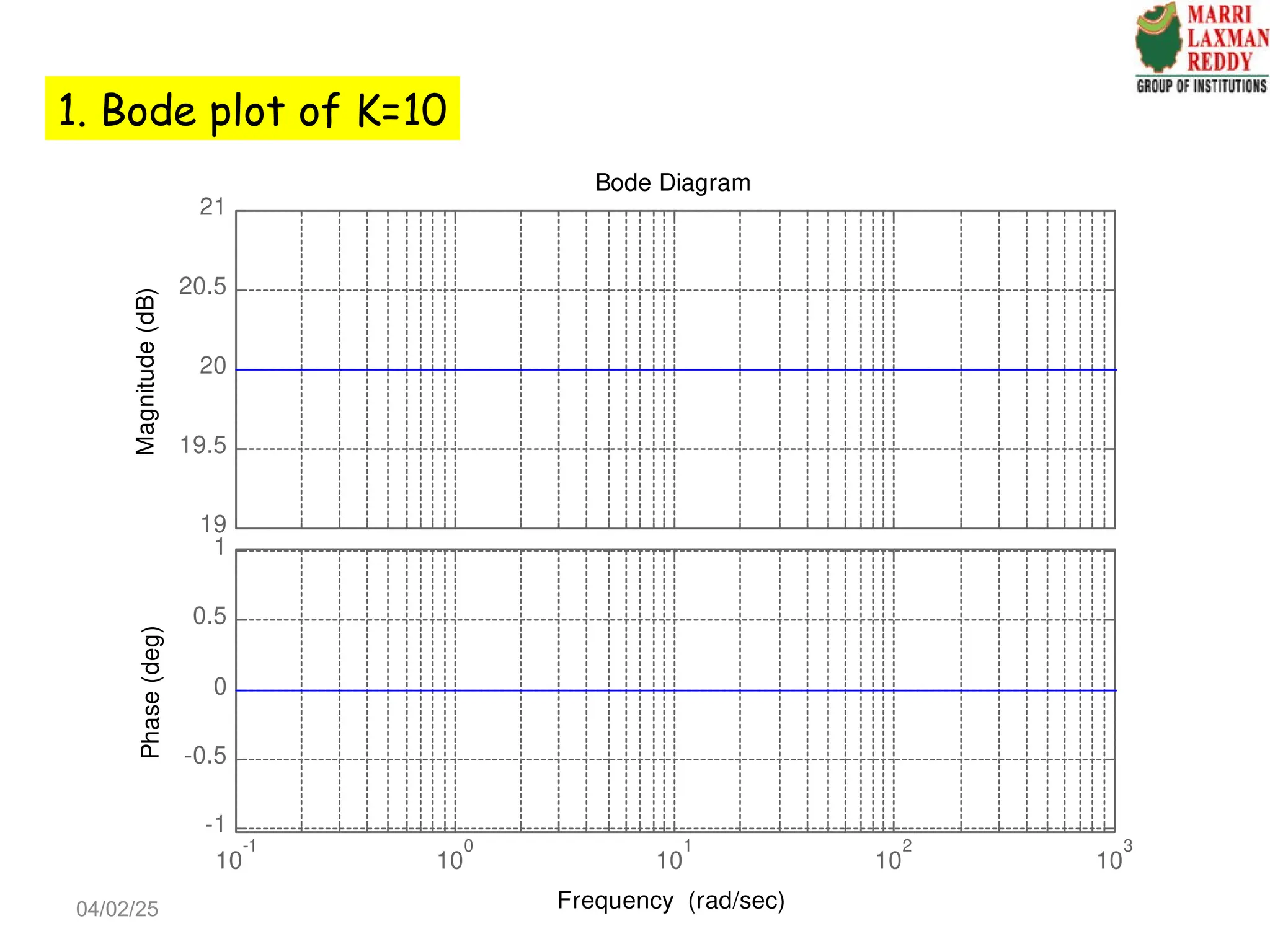

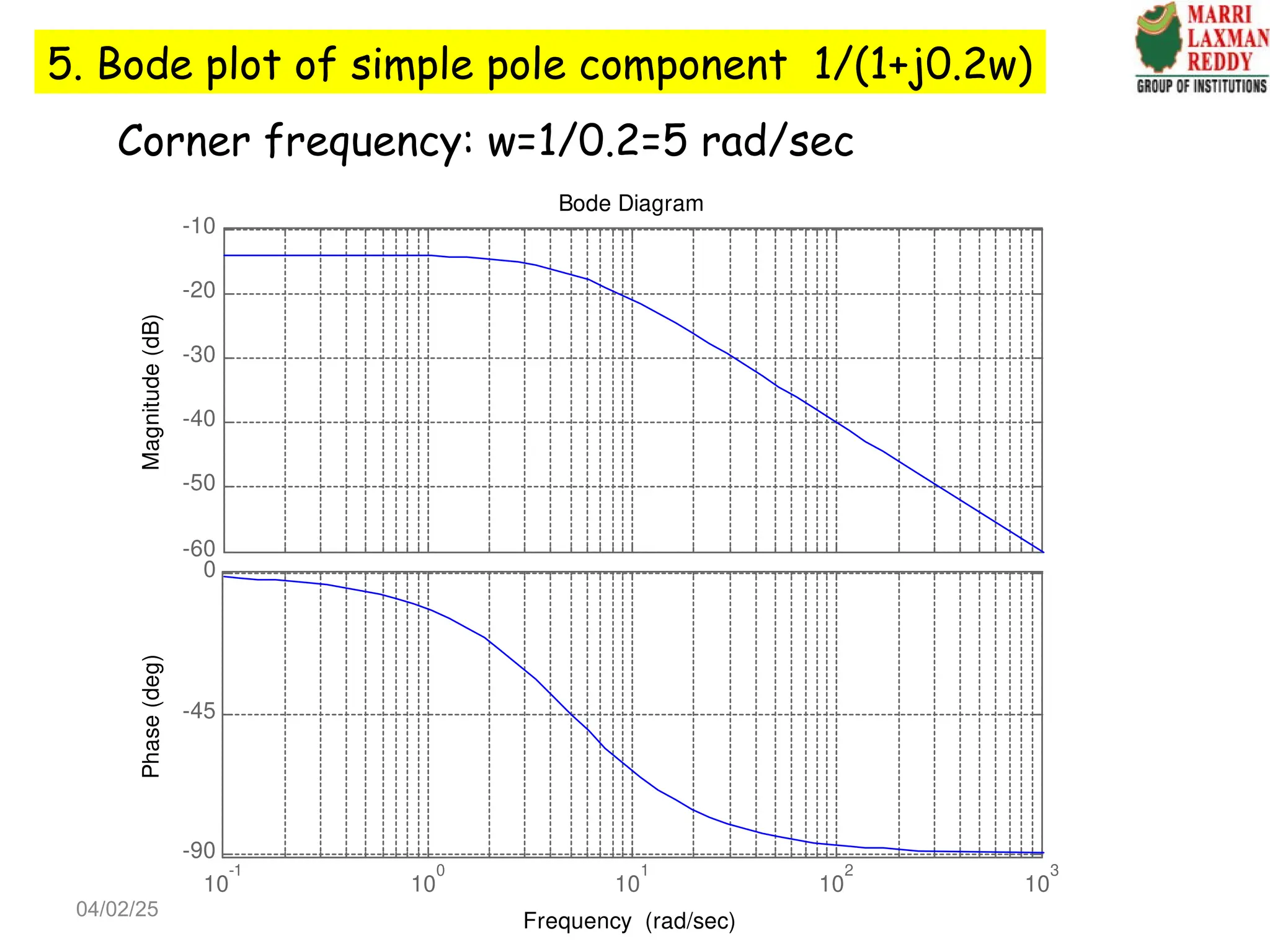

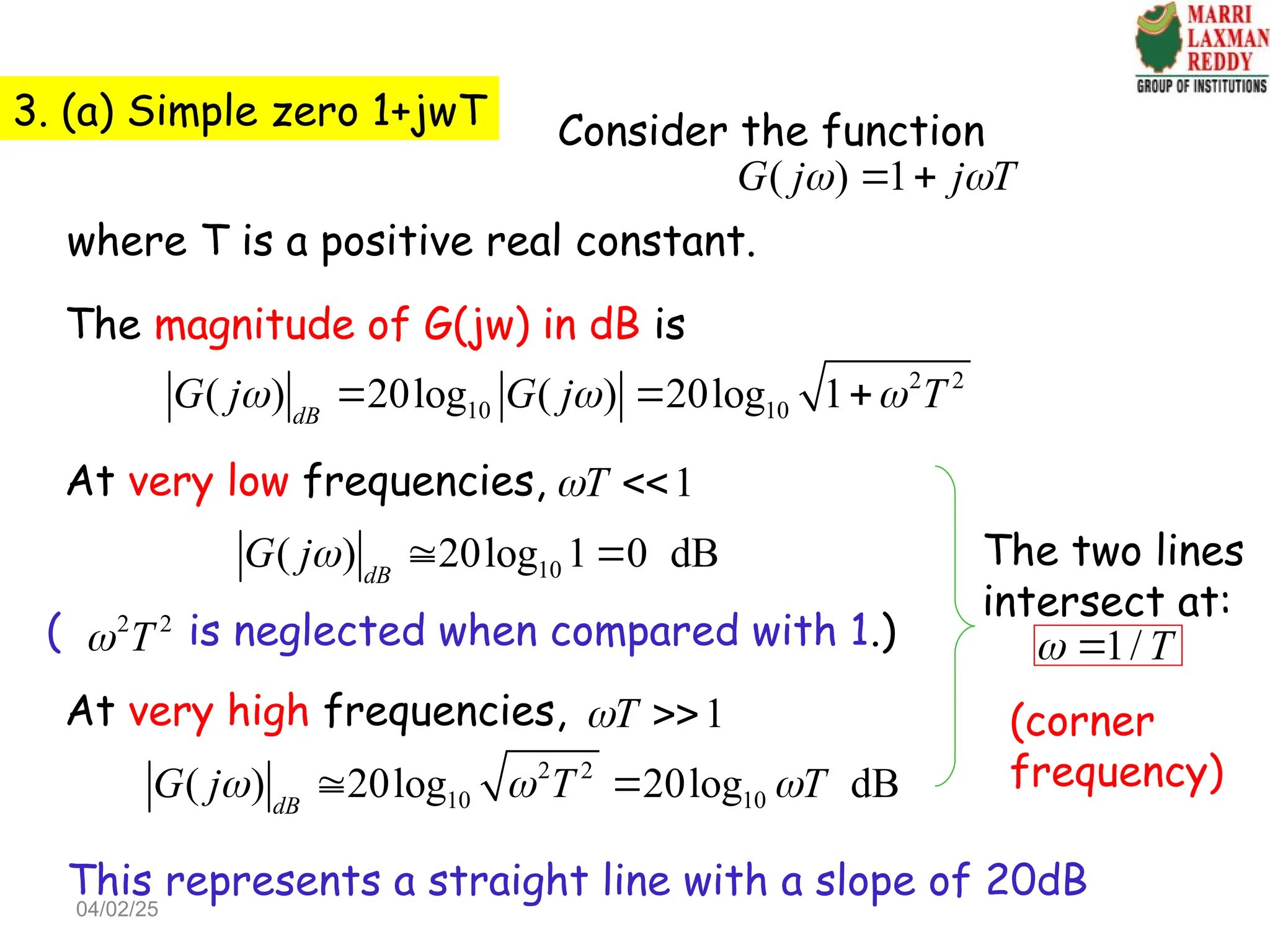

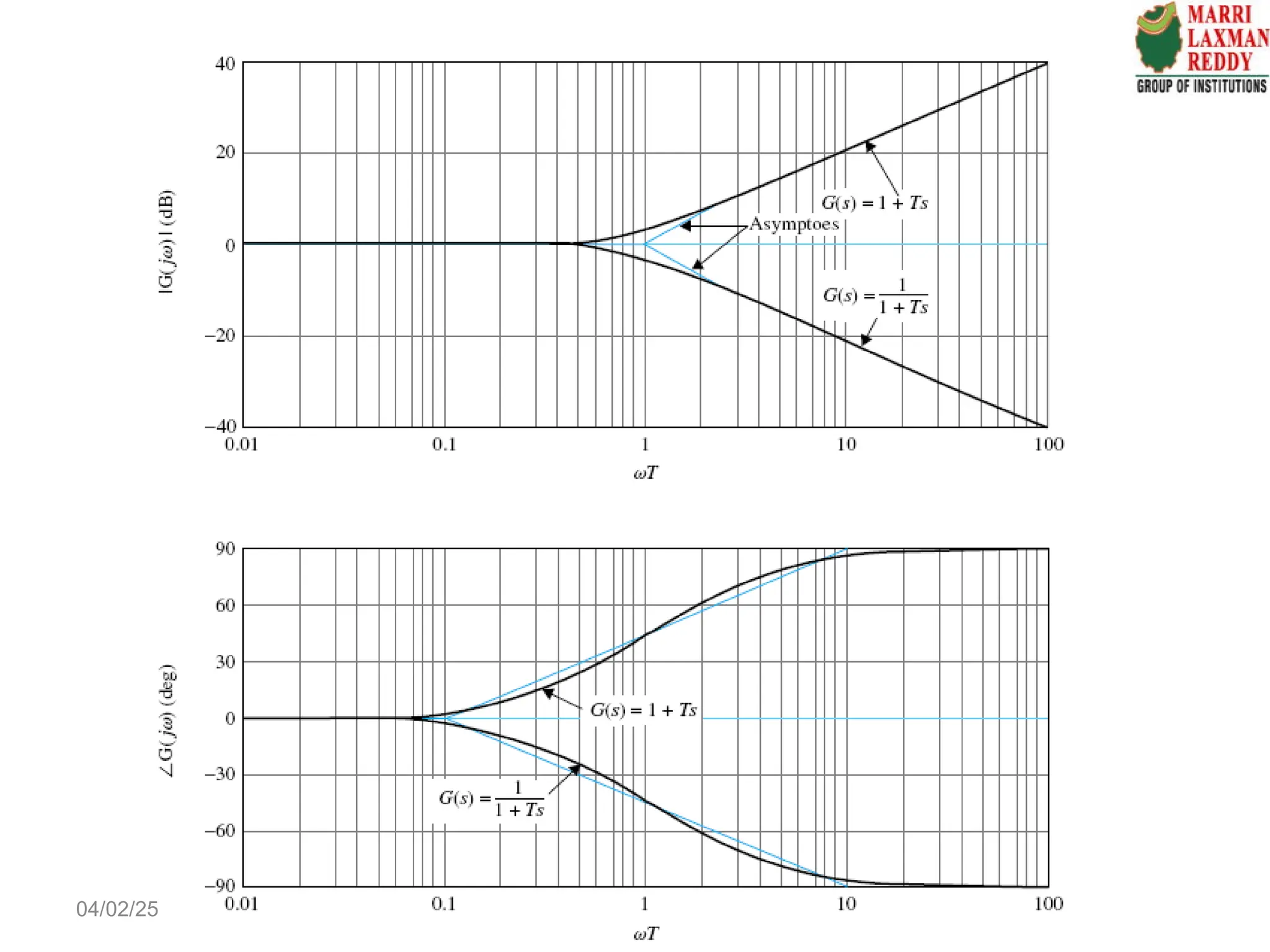

![4. Complex poles and zeros

Consider the second-order transfer function

2

2 2 2 2

1

( )

2 1 (2 ) (1 )

n

n n n n

G s

s s s s

We are interested only in the case when ζ ≤ 1, since

otherwise G(s) would have two unequal real poles, and

the Bode plot can be obtained by considering G(s) as the

product of two transfer functions with simple poles.

By letting s=jw, G(s) becomes

2 2

1

( )

[1 ( )] 2 ( )

n n

G j

j

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-67-2048.jpg)

![2 2

1

( )

[1 ( )] 2 ( )

n n

G j

j

The magnitude of G(jw) in dB is

10

2 2 2 2 2

10

( ) 20log ( )

20log [1 ( )] 4 ( )

dB

n n

G j G j

At very low frequencies, / 1

n

10

( ) 20log 1 0 dB

dB

G j

At very high frequencies, / 1

n

4

10 10

( ) 20log ( ) 40log ( ) dB

n n

dB

G j

This equation represents a straight line with a slope of

40 dB decade in the Bode plot coordinates.

The two lines

intersect at:

n

(corner

frequency)

04/02/25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/555328898-unit-4-1-ppt-cs-250204034236-5724e0e0/75/555328898-Unit-4-1-PPT-CS-ppt-introduction-68-2048.jpg)