The document discusses the construction of natural phenomena in science. It addresses questions around what phenomena are, how we identify them, and whether they are self-presenting, theory-based, or just patterns in data.

The key points are:

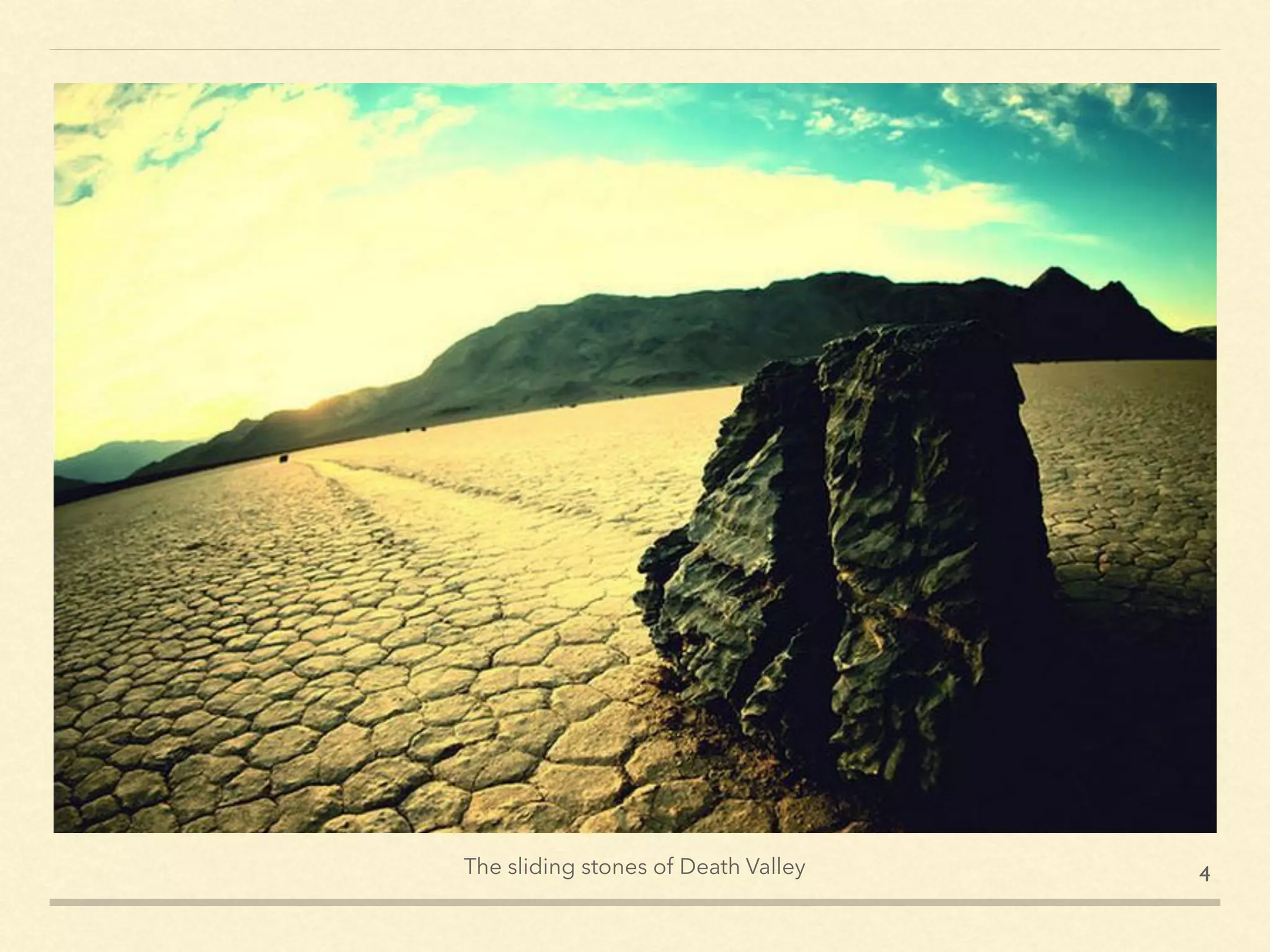

1) Phenomena are observable regularities with salient characteristics that recur under certain conditions.

2) Our observations and categories of phenomena are influenced by our theories and expectations, but we can also identify phenomena in the absence of theory.

3) Phenomena are patterns we discern in observational data based on prior experience with clear cases, but they need not be theory-based. Species are examples of phenomena.

![What are phenomena?

Hobbes: “… such things as appear, or are shown to us by nature,

we call phenomena or appearances” [De Corpore, IV, ch XXV.]

Bogen and Woodward hold that phenomena are derived from

data, which are recorded measurements

They speak of “phenomena of interest”

Phenomena are (acc. to B&W) stable interactions with

repeatable characteristics, and of a limited set of variables/

causes

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-2-2048.jpg)

![But how do we identify phenomena?

Hacking: “Undoubtedly people tend to notice things that are

interesting, surprising, and so forth, and such expectations and

interests are influenced by theories they may hold – not that we

should play down the possibility of the gifted ‘pure’ observer either.”

[Representing and Intervening p179]

It is the noticing of phenomena I wish to discuss today

Are phenomena self-presenting?

Are they theory-based?

Are they just patterns in data? If so, which patterns?

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-3-2048.jpg)

![Hacking said it first, of course

“A phenomenon is noteworthy. A phenomenon is

discernible. A phenomenon is commonly an event of a

certain type that occurs regularly under certain

circumstances. The word can also denote a unique event

that we single out as particularly important. When we

know the regularity exhibited in a phenomenon we

express it in a law-like generalization. The very fact of such

a regularity is sometimes called the phenomenon.”

[Representing and Intervening, p221 ]

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-5-2048.jpg)

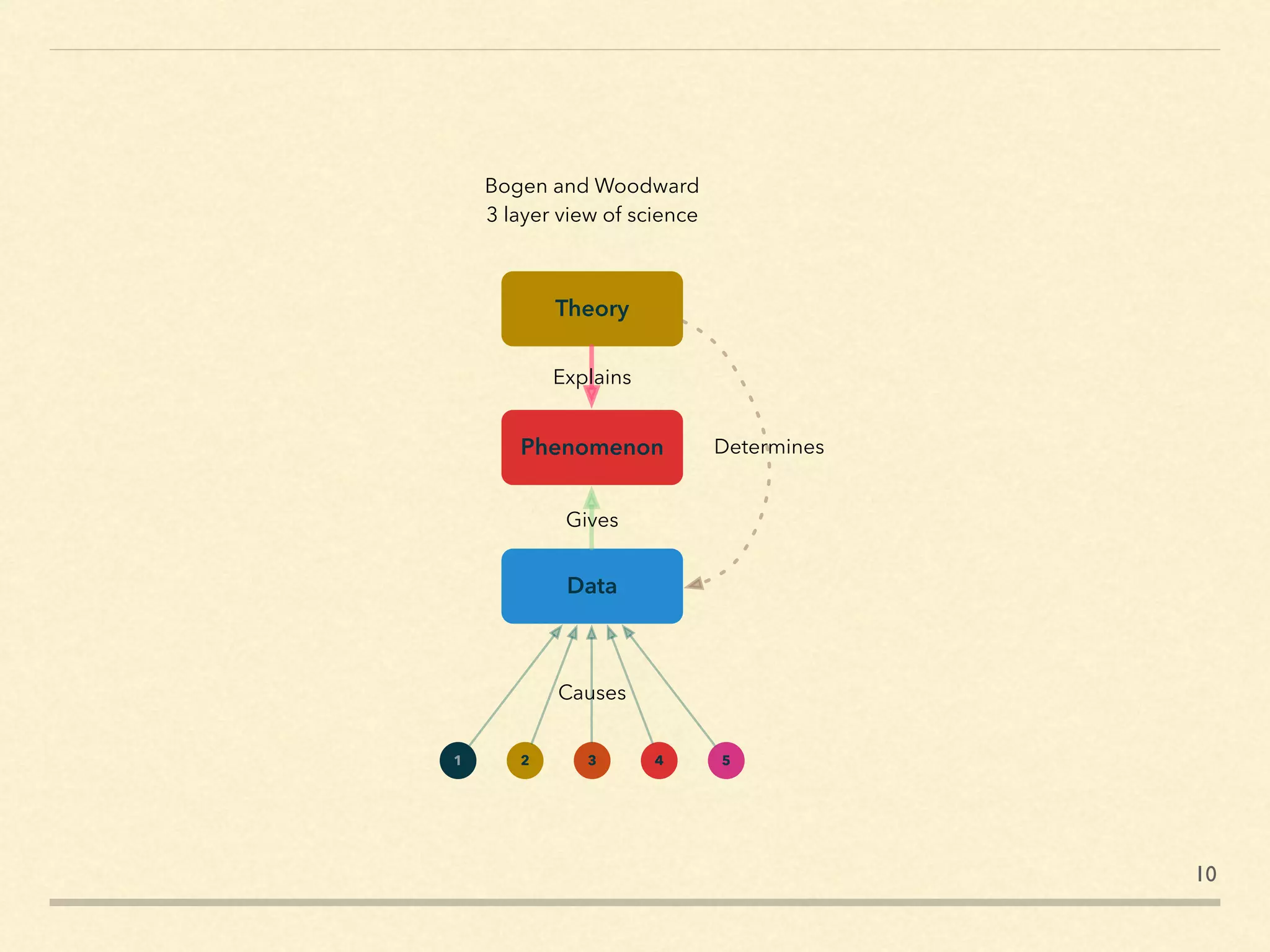

![James F. Woodward, Synthese, [2011] 182:165–179 [emphasis added]

[We] advocated a three-level picture of scientific

theory or, more accurately, of those theories that were in the

business of providing systematic explanations. Explanatory

theories such as classical mechanics, general relativity, and the

electroweak theory that unifies electromagnetic and weak

nuclear forces were understood as providing explanations of

what we called phenomena—features of the world that in

principle could recur under different contexts or conditions. …

Data are public records produced by measurement and

experiment that serve as evidence for the existence or features

of phenomena

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-9-2048.jpg)

![Theory-based accounts

Observation requires either prior or ancillary theory

“However diverse its structure, the physical phenomenon is not simple but

complex. Usually a mass of previously acquired theoretical knowledge and

experience with apparatus is already incorporated in its description.”

[Wolfgang Pauli 1957]

So, either

1. There is no way to start a de novo investigation, or

2. Our evolved dispositions to perceive certain things (our Umwelt), count

as theory

1. must be false; 2. beggars the meaning of “theory” in science

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-13-2048.jpg)

![Empiricist accounts

Naive empiricism: What to attend to?

Abductive phenomena: from observations to best hypothesis

What observations need hypotheses?

Constructive empiricism: empirically adequate, to which empirical

observations?

“a theory is empirically adequate exactly if what it says about the

observable things and events in the world is true—exactly if it ‘saves

the phenomena.’” [van Fraassen 1980, 12]

And so on…

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-14-2048.jpg)

![Species: A case study

All classificatory terms are impossible of exact definition. Their use

always has and always will depend upon the consensus of opinion of

those best qualified by wisdom, experience and natural good sense.

They will never become stable; we shall never cease to amend, to

change, to repudiate old and propose new, because we shall never

reach the final summation of science. [Samuel W. Williston, “What is a

species?”, American Naturalist, (Williston 1908, 184–194)]

The term ‘species’ refers to a concrete phenomenon of nature and

this fact severely constrains the number and kinds of possible

[species] definitions. [Mayr 1996, 263]

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-17-2048.jpg)

![Species: A case study

Over 28 distinct conceptions/definitions of species in play, and 4 replacement

conceptions [Wilkins 2018, Appendix 2]

Scientists do not at all agree on what species are. Nor do they agree on what

counts as sufficient evidence that two organisms are in different species; at least,

not all of the time.

And yet, the standard view is that species are fundamental units of evolution,

ecology, and the other ways that we deal with the biological world.

The very notion of a “level” of biological taxa such as species is itself the outcome

of sociocultural factors—to wit, the need to work out what “kinds” meant in the

Noah’s Ark story so the logistics could be rationalized [Wilkins 2018, p56–62].

If that is the origin, why does species persist among scientists as a category?

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-19-2048.jpg)

![24

Red Wolf, Canis rufus [gray wolf × coyote hybrid]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-24-2048.jpg)

![Let us begin with the naive empiricist.

He says that in observing the world, certain phenomena are

ready-made and call for explanation.

But the Kantian [Massimi 2004–2011] replies that the naive

empiricist must choose what patterns in the data to include in the

phenomenon, and what to exclude as irrelevant or noisy.

Hence, she will say, the naive empiricist has no access to

phenomena until he has a theory of causality, relevance, and

explanation in that (the phenomena’s) domain.

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-29-2048.jpg)

![The Precession of Mercury: A case

study

Consider a phenomenon: the PRECESSION OF MERCURY

It is as clear a phenomenon as you can find in science, but it would not have been a

phenomenon to the Ptolemaic astronomers for the simple reason that they could

not observe it without previously having adopted a heliocentric (or perhaps

Tychonic) model of the solar system, and Newtonian physics (as opposed to, say,

Descartes’ vortex physics).

Yet the observation of the precession of Mercury’s perihelion could be done

without very much in the way of theoretical knowledge, using measuring

instruments that in no way depended upon either theory.

It simply was not an anomaly worth noting until the Newtonian/Copernican model

had been adopted, and it deviated from the expectations of that model.

And even then, it took around 150 years to show up as an anomaly [Le Verrier 1859]

32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-32-2048.jpg)

![Back to observation

If “theory” has any meaning in science, it must not be watered down to include our disposition to

notice mesoscale phenomena that we might eat, navigate, fear or copulate with.

And yet, that set of sensory dispositions is what does underpin scientific investigations

Most of our measuring tools are ways to represent at mesoscale what we cannot otherwise

see or notice.

A telescope and a microscope both present phenomena in ways we can use our evolved

sensory apparatus to observe.

However, as anyone who has used either of these devices knows, some experience is

required to interpret what is seen, and the more a measuring device abstracts the microscale

or macroscale, the more training it takes to be able to interpret what is measured.

So, observation must be done by trained, experienced experts [i.e., include both cultural

scaffolding and personal trial and error learning]

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-34-2048.jpg)

![Newton’s phenomena

35

Phenomenon 1 The circumjovial planets, by radii drawn to the centre of Jupiter, describe areas proportional to the times,

and their periodic times – the fixed stars being at rest – are as the 3/2 powers of their distances from that

centre.

Phenomenon 2 The circumsaturnian planets, by radii drawn to the centre of Saturn, describe areas proportional to the times,

and their periodic times – the fixed stars being at rest – are as the 3/2 powers of their distances from that

centre.

Phenomenon 3 The orbits of the five primary planets – Mercury,Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn – encircle the sun.

Phenomenon 4 The periodic times of the five primary planets and of either the sun about the earth or the earth about the

sun – the fixed stars being at rest – are as the 3/2 powers of their mean distances from the sun.

Phenomenon 5 The primary planets, by radii drawn to the earth, describe areas in no way proportional to the times but, by

radii drawn to the sun, traverse areas proportional to the times.

Phenomenon 6 The moon, by a radius drawn to the centre of the earth, describes areas proportional to the times.

Phenomena from Principia [Walsh 2014]

Despite what might be suggested by their title, [Newton’s] ‘Phenomena’ are not directly observed, but

rather are conclusions based on observations… They invoke not just observations, but planetary theory

in current use by the astronomers of his time (Densmore, 1995: 307).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-35-2048.jpg)

![This is historical, too

Quotes from Walsh 2014:

“ Phænomenon, in Natural Philosophy, signifies any Appearance, Effect, or Operation of a

Natural Body, which offers its self to the Consideration and Solution of an Enquirer

into Nature (Harris, 1708).

“ Phænomenon [...] is in Physicks an extraordinary Appearance in the Heavens or on Earth;

discovered by the observation of the Celestial Bodies, or by Physical Experiments the

Cause of which is not obvious (Harris, 1736)

“ Phænomenon, in philosophy, denotes any remarkable appearance, whether in the

heavens or on earth; and whether discovered by observation or experiments (Macfarquhar

& Bell, 1771).

“ Phenomena I call whatever can be perceived, either things external which become known

through the five senses, or things internal which we contemplate in our minds by thinking.

[Newton, Draft of Principia]

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/50wordssnow-180328054822/75/50-words-for-snow-constructing-scientific-phenomena-37-2048.jpg)