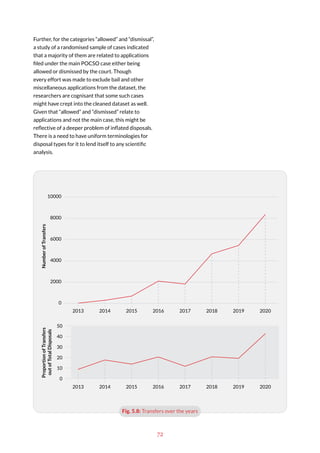

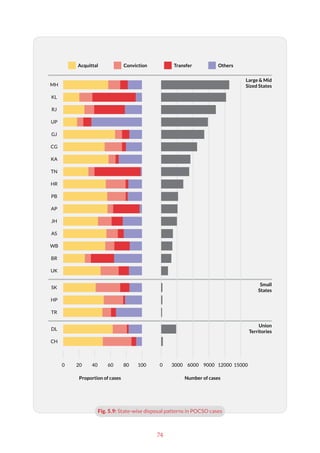

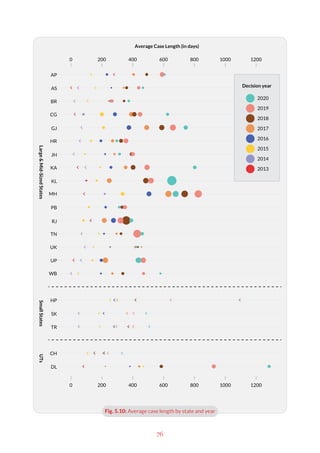

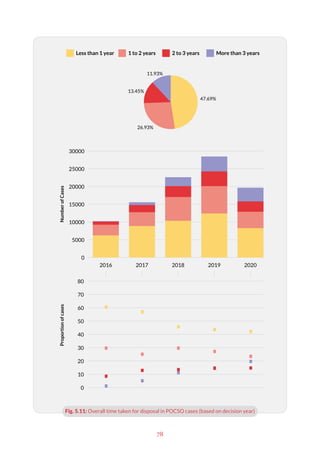

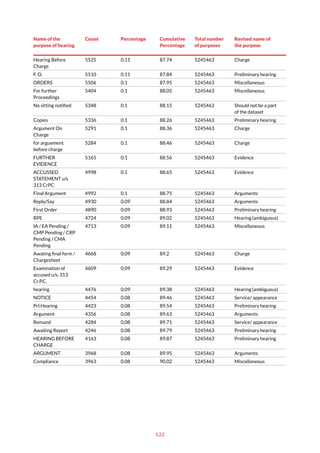

This report marks a decade of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act in India, analyzing its implementation through case laws, policy interventions, and judicial data from ecourts. Key findings reveal significant variations in trial numbers, long pendency rates, and a high ratio of acquittals compared to convictions across different states. Recommendations include legislative changes, improved capacity building for court personnel, and enhanced data accuracy in ecourts to better protect children's rights.

![31

When dealing with bail applications of accused

persons, High Courts have considered the aspect

of consent. In Smti. Ephina Khonglah v State of

Meghalaya,143

the Meghalaya High Court held that

even though the consent of a minor has no legal

validity, one cannot lose sight of the matter while a

plea for bail is being considered by the court.144

While dealing with a case involving a ‘consensual’

relationship, the Delhi High Court remarked that

the police’s filing of cases under the POCSO Act

at the behest of the girl’s family who opposed the

relationship is an unfortunate practice.145

Present position of law

Even as one bench of the Madras High Court was

hailed for its progressive implementation of POCSO,

another Bench of the same court, in Maruthupandi

v State,146

favoured a more literal interpretation of

the Act and held that penalty under POCSO will be

attracted irrespective of whether the relationship

was consensual or not. This uncertainty can only

be resolved if the Supreme Court gives a ruling

on the matter or if the Parliament introduces an

appropriate amendment. Till then sexual acts

between minors will continue to be criminalised and

any decision given will be contingent on the how a

particular bench decides to interpret the law.

The above discussion shows that while some

controversies surrounding the interpretation of

various provisions of the POCSO Act that have

arisen since 2012 have been settled by judicial

pronouncements, many others remain. Even within

each individual issue, while certain elements have

acquired some form of legal certainty, there are

certain questions that still need to be settled.

It is possible that some of these questions will

eventually be answered by the courts. However, for

a few others, legislative intervention, in the form

of amendments to the law, is necessary. The last

143 B.A. No. 14 of 2021 (Meg H.C.) (unreported).

144 In Dharmander Singh v State, B.A. No. 1559 of 2020 (Del H.C.) (unreported).

The Delhi High Court granted bail to the accused while taking into consideration the possibility of a reciprocal

physical relationship between the accused and the minor victim.

145 Pradhuman v State, B.A. No. 2380 of 2021 (Del H.C.) (unreported).

146 CRL.A [MD] No. 209 of 2017.

chapter of this report lists some recommendations in

this regard.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/221117final-pocso-draftjaldi-241202104002-f6ede0a2/85/221117_Final-POCSO-Draft_JALDI-pdf-47-320.jpg)