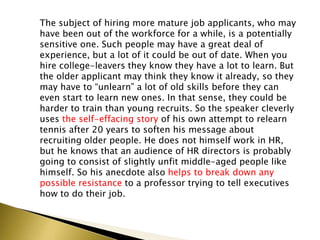

Annette Simmons recommends telling a story before presenting facts because stories help people make sense of information in a way that facts alone cannot. A story engages listeners and primes them to understand the facts in the intended context, rather than risking them drawing their own, unintended conclusions from isolated data. Telling an anecdote about one's own experiences can be even more effective than another person's story as it provides insight into the storyteller's personality and allows listeners to relate more personally.