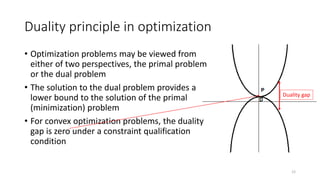

This document summarizes a machine learning course on kernel machines. The course covers feature maps that transform data into higher dimensional spaces to allow nonlinear models to fit complex patterns. It discusses how kernel functions can efficiently compute inner products in these transformed spaces without explicitly computing the feature maps. Specifically, it shows how support vector machines, linear regression, and other algorithms can be kernelized by reformulating them to optimize based on inner products between examples rather than model weights.

![Feature Maps

• Linear models: 𝑦 = 𝑤⊤𝑥 = 𝑖 𝑤𝑖𝑥𝑖 = 𝑤1𝑥1 + ⋯ + 𝑤𝑝𝑥𝑝

• When we cannot fit the data well (non-linear), add non-linear

combinations of features

• Feature map (or basis expansion ) 𝜙 ∶ 𝑋 → ℝ𝑑

𝑦 = 𝑤⊤𝑥 → 𝑦 = 𝑤⊤𝜙(𝑥)

• E.g., Polynomial feature map: all polynomials up to degree 𝑑

𝜙[1, 𝑥1, … , 𝑥𝑝] → [1, 𝑥1, … , 𝑥𝑝, 𝑥1

2

, … , 𝑥𝑝

2, … , 𝑥𝑝

𝑑, 𝑥1𝑥2, … , 𝑥𝑖𝑥𝑗]

• Example with p=1,d=3

𝑦 = 𝑤1𝑥1 → 𝑦 = 𝑤1𝑥1 + 𝑤2𝑥1

2

+ 𝑤3𝑥1

3

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13kernelmachines-230503045718-dcbdbe04/85/13Kernel_Machines-pptx-3-320.jpg)