The document critiques the prevailing metaphor of argument as war in Western culture, highlighting its limitations and misconceptions about productive discourse. It proposes alternative metaphors, such as argument as collaboration or dance, which emphasize dialogue and ethical deliberation rather than combativeness. Furthermore, it discusses various models of argumentation, including classical rhetoric and logical reasoning, underscoring the importance of nuanced and thoughtful engagement in public discussions.

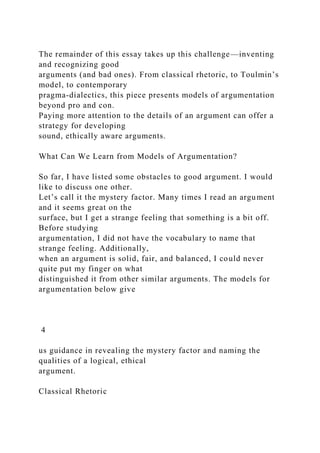

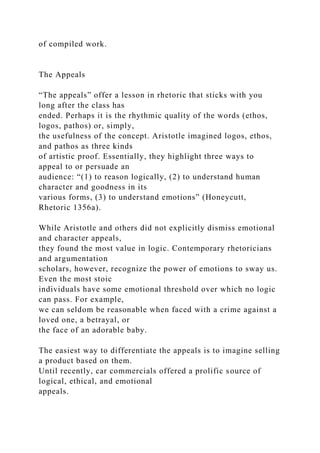

![Logos: Using logic as proof for an argument. For many students

this takes the form of

numerical evidence. But as we have discussed above, logical

reasoning is a kind of

argumentation.

Car Commercial: (Syllogism) Americans love adventure—Ford

Escape

allows for off-road adventure— Americans should buy a Ford

Escape.

OR

The Ford Escape offers the best financial deal.

Ethos: Calling on particular shared values (patriotism),

respected figures of authority

(MLK), or one’s own character as a method for appealing to an

audience.

Car Commercial: Eco-conscious Americans drive a Ford Escape.

OR

[Insert favorite movie star] drives a Ford Escape.

Pathos: Using emotionally driven images or language to sway

your audience.

8

Car Commercial: Images of a pregnant woman being safely

rushed to a

hospital. Flash to two car seats in the back seat. Flash to family](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1findingthegoodargumentorwhybotherwithlogicb-221026114612-6e0b1e82/85/1-Finding-the-Good-Argument-OR-Why-Bother-With-Logic-b-docx-16-320.jpg)

![Print.

Fish, Stanley. “Democracy and Education.” New York Times 22

July 2007: n. pag. Web.

5 May 2010.

Honeycutt, Lee. “Aristotle’s Rhetoric: A Hypertextual Resource

Compiled by Lee

Honeycutt.” 21 June 2004. Web. 5 May 2010.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By.

Chicago: U of Chicago P,

1980. Print.

Murphy, James. Quintilian On the Teaching and Speaking of

Writing. Carbondale:

Southern Illinois UP, 1987. Print.

“Plato, The Dialogues of Plato, vol. 1 [387 AD].” Online

Library of Liberty, n. d. Web. 5

May 2010.

Attribution

(16) “Finding the Good Argument OR Why Bother With

Logic?” http://writingspaces.org/essays/finding-the-good-

argument is by Rebecca Jones licensed

under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

1 Basic Logic

The two most common forms of basic logic that we apply in our

daily lives and our written arguments are induction and

deduction. Of these two forms of reasoning, we far more](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1findingthegoodargumentorwhybotherwithlogicb-221026114612-6e0b1e82/85/1-Finding-the-Good-Argument-OR-Why-Bother-With-Logic-b-docx-31-320.jpg)