vijay madanlal case.pdf

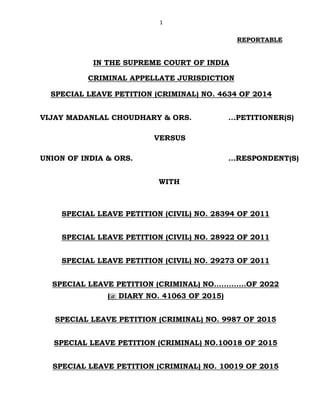

- 1. 1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL APPELLATE JURISDICTION SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 4634 OF 2014 VIJAY MADANLAL CHOUDHARY & ORS. ...PETITIONER(S) VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & ORS. ...RESPONDENT(S) WITH SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 28394 OF 2011 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 28922 OF 2011 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 29273 OF 2011 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO.............OF 2022 (@ DIARY NO. 41063 OF 2015) SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 9987 OF 2015 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO.10018 OF 2015 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 10019 OF 2015 Digitally signed by DEEPAK SINGH Date: 2022.07.27 11:48:08 IST Reason: Signature Not Verified

- 2. 2 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 993 OF 2016 TRANSFER PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 150 OF 2016 TRANSFER PETITION (CRIMINAL) NOS.151-157 OF 2016 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 152 OF 2016 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 11839 OF 2019 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 2890 OF 2017 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 5487 OF 2017 CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 1269 OF 2017 CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 1270 OF 2017 CRIMINAL APPEAL NOS. 1271-1272 OF 2017 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 202 OF 2017 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO............OF 2022 (@ DIARY NO(S). 9360 OF 2018) SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO............OF 2022 (@ DIARY NO(S). 9365 OF 2018)

- 3. 3 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO............OF 2022 (@ DIARY NO(S). 17000 OF 2018) SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO............OF 2022 (@ DIARY NO(S). 17462 OF 2018) SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO............OF 2022 (@ DIARY NO(S). 20250 OF 2018) SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO............OF 2022 (@ DIARY NO(S). 22529 OF 2018) SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1534 OF 2018 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NOS. 1701-1703 OF 2018 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1705 OF 2018 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 2971 OF 2018 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 4078 OF 2018 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 5444 OF 2018 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 6922 OF 2018 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 7408 OF 2018

- 4. 4 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 8156 OF 2018 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 11049 OF 2018 CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 223 OF 2018 CRIMINAL APPEAL NOS. 391-392 OF 2018 CRIMINAL APPEAL NOS. 793-794 OF 2018 CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 1114 OF 2018 CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 1115 OF 2018 CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 1210 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 26 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 33 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 75 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 117 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 173 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 175 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 184 OF 2018

- 5. 5 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 226 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 251 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 309 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 333 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 336 OF 2018 TRANSFERRED CASE (CRIMINAL) NO. 3 OF 2018 TRANSFERRED CASE (CRIMINAL) NO. 4 OF 2018 TRANSFERRED CASE (CRIMINAL) NO. 5 OF 2018 TRANSFER PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 1583 OF 2018 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 244 OF 2019 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 3647 OF 2019 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NOS. 4322-4324 OF 2019 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 4546 OF 2019 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 5153 OF 2019

- 6. 6 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 5350 OF 2019 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 6834 OF 2019 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 8111 OF 2019 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 8174 OF 2019 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 9541 OF 2019 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 9652 OF 2019 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 10627 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 9 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 16 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 49 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 118 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 119 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 122 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 127 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 139 OF 2019

- 7. 7 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 147 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 173 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 205 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 212 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 217 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 239 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 244 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 253 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 261 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 263 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 266 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 267 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 272 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 273 OF 2019

- 8. 8 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 283 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 285 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 286 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 287 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 288 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 289 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 298 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 299 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 300 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 303 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 305 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 306 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 308 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 309 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 313 OF 2019

- 9. 9 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 326 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 346 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 365 OF 2019 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 367 OF 2019 CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 682 OF 2019 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 647 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 260 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 618 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1732 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 2023 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 2814 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 3366 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 3474 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 5536 OF 2020

- 10. 10 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 6128 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 6172 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 6303 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 6456 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 6660 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 5 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 9 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 28 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 35 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 36 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 39 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 49 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 52 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 60 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 61 OF 2020

- 11. 11 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 89 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 90 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 91 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 93 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 124 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 137 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 140 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 142 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 145 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 169 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 184 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 221 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 223 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 228 OF 2020

- 12. 12 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 239 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 240 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 259 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 267 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 285 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 286 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 311 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 329 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 366 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 380 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 385 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 387 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 404 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 410 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 411 OF 2020

- 13. 13 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 429 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 1401 OF 2020 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO............OF 2022 (@ DIARY NO(S). 8626 OF 2021) SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO............OF 2022 (@ DIARY NO(S). 31616 OF 2021) SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO............OF 2022 (@ DIARY NO. 11605 OF 2021) SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 609 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 734 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1031 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1072 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1073 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1107 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1355 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1440 OF 2021

- 14. 14 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1403 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1586 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1855 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 1920 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NOS. 2050-2054 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 2237 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 2250 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 2435 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 2818 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 3228 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 3274 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 3439 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 3514 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 3629 OF 2021

- 15. 15 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 3769 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 3813 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 3921 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 4024 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 4834 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 5156 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 5174 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 5252 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 5457 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 5652 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NOS. 5696-5697 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 6189 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 6338 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 6847 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NOS. 7021-7023 OF 2021

- 16. 16 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 8429 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CIVIL) NOS. 8764-8767 OF 2021 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 20310 OF 2021 TRANSFER PETITION (CRIMINAL) No. 435 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) No. 56 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 4 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 6 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 11 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 18 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 19 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 21 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 27 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 33 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 40 OF 2021

- 17. 17 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 47 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 66 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 69 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 144 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 179 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 199 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 207 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 239 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 263 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 268 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 282 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 301 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 323 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 359 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 370 OF 2021

- 18. 18 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 303 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 305 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 453 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 454 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 475 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 520 OF 2021 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 532 OF 2021 J U D G M E N T A.M. KHANWILKAR, J. Table of Contents Particulars Paragraph No(s). Preface 1(a)-(d) Submissions of the Private Parties • Mr. Kapil Sibal, Senior Counsel 2(i)–(xxiii) • Mr. Sidharth Luthra, Senior Counsel 3(i)–(iii) • Dr. Abhishek Manu Singhvi, Senior Counsel 4(i)–(ix)

- 19. 19 • Mr. Mukul Rohatgi, Senior Counsel 5(i)-(iii) • Mr. Amit Desai, Senior Counsel 6(i)-(iii) • Mr. S. Niranjan Reddy, Senior Counsel 7(i)-(ii) • Dr. Menaka Guruswamy, Senior Counsel 8(i)-(v) • Mr. Aabad Ponda, Senior Counsel 9(i)-(ii) • Mr. Siddharth Aggarwal, Senior Counsel 10(i)-(iii) • Mr. Mahesh Jethmalani, Senior Counsel 11(i)-(iii) • Mr. Abhimanyu Bhandari, Counsel 12(i)-(iv) • Mr. N. Hariharan, Senior Counsel 13 • Mr. Vikram Chaudhari, Senior Counsel 14(i)-(v) • Mr. Akshay Nagarajan, Counsel 15 Submissions of the Union of India • Mr. Tushar Mehta, Solicitor General of India 16(i)-(lxxx) • Mr. S.V. Raju, Additional Solicitor General of India 17(i)-(lxvi) Consideration • The 2002 Act 19-22 • Preamble of the 2002 Act 23-24 • Definition Clause 25-36 • Section 3 of the 2002 Act 37-55 • Section 5 of the 2002 Act 56-70 • Section 8 of the 2002 Act 71-76 • Searches and Seizures 77-86 • Search of persons 87

- 20. 20 • Arrest 88-90 • Burden of proof 91-103 • Special Courts 104-114 • Bail 115-149 • Section 50 of the 2002 Act 150-173 • Section 63 of the 2002 Act 174 • Schedule of the 2002 Act 175 & 175A • ECIR vis-à-vis FIR 176-179 • ED Manual 180-181 • Appellate Tribunal 182 • Punishment under Section 4 of the 2002 Act 183-186 Conclusion 187(i)-(xx) Order 1-7 PREFACE 1. In the present batch of petition(s)/appeal(s)/case(s), we are called upon to deal with the pleas concerning validity and interpretation of certain provisions of the Prevention of Money- Laundering Act, 20021 and the procedure followed by the 1 For short, “PMLA” or “the 2002 Act”

- 21. 21 Enforcement Directorate2 while inquiring into/investigating offences under the PMLA, being violative of the constitutional mandate. (a) It is relevant to mention at the outset that after the decision of this Court in Nikesh Tarachand Shah vs. Union of India & Anr.3, the Parliament amended Section 45 of the 2002 Act vide Act 13 of 2018, so as to remove the defect noted in the said decision and to revive the effect of twin conditions specified in Section 45 to offences under the 2002 Act. This amendment came to be challenged before different High Courts including this Court by way of writ petitions. In some cases where relief of bail was prayed, the efficacy of amended Section 45 of the 2002 Act was put in issue and answered by the concerned High Court. Those decision(s) have been assailed before this Court and the same is forming part of this batch of cases. At the same time, separate writ petitions have been filed to challenge several other provisions of the 2002 Act and all those cases have been tagged and heard together as overlapping issues have been raised by the parties. 2 For short, “ED” 3 (2018) 11 SCC 1

- 22. 22 (b) We have various other civil and criminal writ petitions, appeals, special leave petitions, transferred petitions and transferred cases before us, raising similar questions of law pertaining to constitutional validity and interpretation of certain provisions of the other statutes including the Customs Act, 19624, the Central Goods and Services Tax Act, 20175, the Companies Act, 20136, the Prevention of Corruption Act, 19887, the Indian Penal Code, 18608 and the Code of Criminal Procedure, 19739 which are also under challenge. However, we are confining ourselves only with challenge to the provisions of PMLA. (c) As aforementioned, besides challenge to constitutional validity and interpretation of provisions under the PMLA, there are special leave petitions filed against various orders of High Courts/subordinate Courts across the country, whereby prayer for grant of bail/quashing/discharge stood rejected, as also, special 4 For short, “1962 Act” or “the Customs Act” 5 For short, “CGST Act” 6 For short, “Companies Act” 7 For short, “PC Act” 8 For short, “IPC” 9 For short, “Cr.P.C. or “the 1973 Code”

- 23. 23 leave petitions concerned with issues other than constitutional validity and interpretation. Union of India has also filed appeals/special leave petitions; and there are few transfer petitions filed under Article 139A(1) of the Constitution of India. (d) Instead of dealing with facts and issues in each case, we will be confining ourselves to examining the challenge to the relevant provisions of PMLA, being question of law raised by parties. SUBMISSIONS OF THE PRIVATE PARTIES 2. Mr. Kapil Sibal, learned senior counsel appearing for the private parties/petitioners in the concerned matter(s) submitted that the procedure followed by the ED in registering the Enforcement Case Information Report10 is opaque, arbitrary and violative of the constitutional rights of an accused. It was submitted that the procedure being followed under the PMLA is draconian as it violates the basic tenets of the criminal justice system and the rights enshrined in Part III of the Constitution of India, in particular Articles 14, 20 and 21 thereof. 10 For short, “ECIR”

- 24. 24 (i) A question was raised as to whether there can be a procedure in law, where penal proceedings can be started against an individual, without informing him of the charges? It was contended that as per present situation, the ED can arrest an individual on the basis of an ECIR without informing him of its contents, which is per se arbitrary and violative of the constitutional rights of an accused. The right of an accused to get a copy of the First Information Report10A at an early stage and also the right to know the allegations as an inherent part of Article 21. Reference was made to Youth Bar Association of India vs. Union of India & Anr.11 in support of this plea. Further, as per law, the agencies investigating crimes need to provide a list of all the documents and materials seized to the accused in order to be consistent with the principles of transparency and openness12. It was also submitted that under the Cr.P.C., every FIR registered by an officer under Section 154 thereof is to be forwarded to the jurisdictional Magistrate. However, this procedure is not being followed in ECIR cases. Further, violation of Section 157 of the 10A For short, “FIR” 11 (2016) 9 SCC 473 (Para 11.1); and Court on its Own Motion vs. State, 2010 SCC OnLine Del 4309 (Paras 39 & 54) 12 Criminal Trials Guidelines Regarding Inadequacies and Deficiencies, In re, vs. State of Andhra Pradesh & Ors., (2021) 10 SCC 598 (Para 11); also see: Nitya Dharmananda & Anr. vs. Gopal Sheelum Reddy & Anr., (2018) 2 SCC 93 (Para 8).

- 25. 25 Cr.P.C. was also alleged and it was submitted that this has led to non-compliance with the procedure prescribed under the law (Cr.P.C.) and the law laid down by this Court in catena of decisions. It was vehemently argued that in some cases the ECIR is voluntarily provided, while in others it is not, which is completely arbitrary and discriminatory. (ii) It was argued that as per definition of Section 3 of the PMLA, the accused can either directly or indirectly commit money- laundering if he is connected by way of any process or activity with the proceeds of crime and has projected or claimed such proceeds as untainted property. In light of this, it was suggested that the investigation may shed some light on such alleged proceeds of crime, for which, facts must first be collected and there should be a definitive determination whether such proceeds of crime have actually been generated from the scheduled offence. Thus, there must be at least a prima facie quantification to ensure that the threshold of the PMLA is met and it cannot be urged that the ECIR is an internal document. Therefore, in the absence of adherence to

- 26. 26 the requirements of the Cr.P.C. and the procedure established by law, these are being violated blatantly13. (iii) An anomalous situation is created where based on such ECIR, the ED can summon accused persons and seek details of financial transactions. The accused is summoned under Section 50 of the PMLA to make such statements which are treated as admissible in evidence. Throughout the process, the accused might well be unaware of the allegations against him. It is clear that Cr.P.C. has separate provisions for summoning of the accused under Section 41A and for witnesses under Section 160. The same distinction is absent under the PMLA. Further, Chapter XII of the Cr.P.C. is not being followed by the ED and, as such, there are no governing principles of investigation, no legal criteria and guiding principles which are required to be followed. As such, the initiation of investigation by the ED, which can potentially curtail the liberty of the individual, would suffer from the vice of Article 14 of the Constitution of India14 . 13 Lalita Kumari vs. Government of Uttar Pradesh and Ors., (2014) 2 SCC 1 (Para 120.1) 14 E.P. Royappa vs. State of Tamil Nadu & Anr., (1974) 4 SCC 3; also see: S.G. Jaisinghani vs. Union of India and Ors, (1967) 2 SCR 703 and Nikesh Tarachand Shah, (supra at Footnote No.3) (Paras 21-23).

- 27. 27 (iv) Mr. Sibal, while referring to the definition of “money- laundering” under Section 3 of the PMLA, submitted that the ED must satisfy itself that the proceeds of crime have been projected as untainted property for the registration of an ECIR or the application of the PMLA. It has been vehemently argued that the offence of money-laundering requires the proceeds of crime to be mandatorily ‘projected or claimed’ as ‘untainted property’. Meaning thereby that Section 3 is applicable only to the generation of proceeds of crime, such proceeds being projected or claimed as untainted property. It is stated that the pertinent condition of ‘and’ projecting or claiming cannot be ousted and made or interpreted to be ‘or’ by the Explanation that has been brought about by way of the amendment made vide Finance (No.2) Act, 2019. It has been submitted that such an act would also be unconstitutional, as being enlarging the ambit of a principal section by way of adding an Explanation. (v) It is also stated that the general practice is that the ED registers an ECIR immediately upon an FIR of a predicate offence being registered. The cause of action being entirely different from the predicate offence, as such, can lead to a situation where there is no difference between the predicate offence and money-laundering. In

- 28. 28 support of the said argument, reliance was placed on the Article 3 of the Vienna Convention15 , where words like “conversion or transfer of property”, “for the purpose of concealing or disguising the illicit origin of the property or of assisting any person who is involved in the commission of such an offence or offences to evade the legal consequences of his actions”, have been used. It is urged that what was sought to be criminalised was not the mere acquisition and use of proceeds of crime, but it was the conversion or transfer for the purpose of either concealing or disguising the illicit origin of the property to evade the legal consequences of one’s actions. Reference was also made to the Preamble of the PMLA which refers to India’s global commitments to combat the menace of money-laundering. Learned counsel has then referred to the definition of “money- laundering” as per the Prevention of Money-Laundering Bill, 199916 to show how upon reference to the Select Committee of the Rajya Sabha, certain observations were made and, hence, the amendment was effected, wherein the words “and projecting it as untainted 15 United Nations adopted and signed the Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (hereinafter referred to as “Vienna Convention” or “the 1988 Convention” or “the UN Drugs Convention”, as the case may be) 16 For short, “1999 Bill”

- 29. 29 property” were added to the definition which was finally passed in the form of PMLA. We have reproduced the relevant sections/provisions hereinbelow at the appropriate place. Reliance has also been placed on the decision of Nikesh Tarachand Shah17 . (vi) The safeguard provided by Section 173 of the Cr.P.C., it is argued, was present in the original enactment of 2002 (PMLA). The same has now supposedly been whittled down by various amendments over the years. It has been submitted that by way of amendments in 2009, proviso have been added to Sections 5 and 17, which have diluted certain safeguards. Further, it is submitted that the safeguard under Section 17(1) has been totally done away with in the amendment made in 2019. To further this argument, it has been suggested that the filing of chargesheet in respect of a predicate offence was impliedly there in Section 19 of the PMLA, since there is a requirement which cannot be fulfilled sans an investigation, to record reasons to believe that ‘any person has been guilty of an offence punishable under this Act’. In respect of Section 50, it is urged that though there is no threshold mentioned in the 17 Supra at Footnote No.3 (Para 11)

- 30. 30 Act, yet the persons concerned should be summoned only after the registration of the ECIR. It is, thus, submitted that any attempt to prosecute under the PMLA without prima facie recordings would be inconsistent with the Act itself and violative of the fundamental rights. (vii) It is urged that the derivate Act cannot be more onerous than the original. It is suggested that the proceeds of crime and the predicate offence are entwined inextricably. Further, the punishment for generation of the proceeds of crime cannot be disproportionate to the punishment for the underlying predicate offence. The same analogy ought to apply to the procedural protections, such as those provided under Section 41A of the Cr.P.C., which otherwise would be foul of the constitutional protections under Article 21. (viii) Learned counsel has also challenged the aspect of the Schedule being overbroad and inconsistent with the PMLA and the predicate offences. It is argued that even in the Statements of Objects and Reasons of the 1999 Bill, it has been stated that the Act was brought in to curb the laundering stemming from trade in narcotics and drug related crimes. Reference is also made to the

- 31. 31 various conventions that are part of the jurisprudence behind the PMLA18 . It was to be seen in light of organised crime, unlike its application today to less heinous crimes such as theft. It is submitted that there was no intention or purpose to cover offences under the PMLA so widely. It is also submitted that there are certain offences which are less severe and heinous than money-laundering itself and that the inclusion of such offences in the Schedule does not have a rational nexus with the objects and reasons of the PMLA and the same is unreasonable, arbitrary and violative of Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution of India. (ix) It has been submitted that the PMLA cannot be a standalone statute. To bolster this claim, reliance has been placed on speeches made by Ministers in the Parliament. Further reliance has been placed on K.P. Varghese vs. Income Tax Officer, Ernakulum & Anr.19 , Union of India & Anr. vs. Martin Lottery Agencies 18 United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, 1988 (for short, “Vienna Convention”); Basle Statement of Principles, 1989; Forty Recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering, 1990; Political Declaration and Global Program of Action adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 23.02.1990; and Resolution passed at the UN Special Session on countering World Drug Problem Together – 8th to 10th June 1998. 19 (1981) 4 SCC 173 (Para 8)

- 32. 32 Limited20 and P. Chidambaram vs. Directorate of Enforcement21 . (x) Our attention is also drawn to the provisions which have now been replaced in the statute. Prior to 2013 amendment, Section 8(5) of the PMLA was to the following effect: - “8. Adjudication— …. (5) Whereon conclusion of a trial for any scheduled offence, the person concerned is acquitted, the attachment of the property or retention of the seized property or record under sub-section (3) and net income, if any, shall cease to have effect.” However, vide amendment in 2013, the words ‘trial for any scheduled offence’ were replaced with the words ‘trial of an offence under this Act’. It is urged that for the property to qualify as proceeds of crime, it must be connected in some way with the activity related to the scheduled offence. Meaning thereby that if there is no scheduled offence, there can be no property derived directly or indirectly; thus, an irrefutable conclusion that a scheduled offence is a pre-requisite for generation of proceeds of crime. 20 (2009) 12 SCC 209 (Para 38) 21 (2019) 9 SCC 24 (Para 25)

- 33. 33 (xi) It is further argued that an Explanation has been added to Section 44(1)(d) of the PMLA by way of Finance (No. 2) Act, 2019, which posits that a trial under the PMLA can proceed independent of the trial of scheduled offence. It is submitted that the Explanation is being given a mischievous interpretation when it ought to be read plainly and simply. It is stated that the Explanation relates only to the Special Court and not the trial of the scheduled offence. It is submitted that a Special Court can never convict a person under the PMLA without returning a finding that a scheduled offence has been committed. (xii) It is submitted that the application of Cr.P.C. is necessary since it is a procedure established by law and there cannot be an investigation outside the purview of Section 154 or 155 of the Cr.P.C. Reference is made to the constitutional safeguards of reasonability and fairness. It is submitted that the Act itself, under Section 65, provides for the applicability of the Cr.P.C.22 It is pointed out that several safeguards, procedural in nature are being violated. To illustrate a few - non registration of FIR, lack of a case diary, 22 Ashok Munilal Jain & Anr. vs. Assistant Director, Directorate of Enforcement, (2018) 16 SCC 158 (Paras 3-5)

- 34. 34 restricted access to the ECIR, violation of Section 161 of the Cr.P.C., Section 41A of the Cr.P.C., lack of magisterial permission under Section 155 of the Cr.P.C. Such unguided use of power to investigate and prosecute any person violates Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. (xiii) Another argument raised by the learned counsel is that the ED officers are police officers. It is submitted that the determination of the same depends on: (1) what is the object and purpose of the special statute and (2) the nature of power exercised by such officers? The first argument in this regard is that if it can be shown that in order to achieve the objectives of the special statute - preventive and detection steps to curb crime are permitted and coercive powers are vested, then such an officer is a police officer. Further, such an officer is covered within the ambit of Sections 25 and 26 of the Indian Evidence Act, 187223. In support of the test to gauge the objective of the statute, reference has been made to State of Punjab vs. Barkat Ram24 , wherein it was held —a customs 23 For short, “the 1872 Act” or “the Evidence Act” 24 (1962) 3 SCR 338; Also see: Tofan Singh vs. State of Tamil Nadu, 2020 SCC OnLine SC 882 (Para 88)

- 35. 35 officer is not a police officer within the meaning of Section 25 of the 1872 Act. It is also stated that police officers had to be construed not in a narrow way but in a wide and popular sense. Reference is made to Sections 17 and 18 of the Police Act, 186125, whereunder an appointment of special police officers can be made. Thus, it is stated that it is not necessary to be enrolled under the 1861 Act, but if one is invested with the same powers i.e., the powers for prevention and detection of crime, one will be a police officer. Then, the PMLA is distinguished from the 1962 Act, Sea Customs Act, 187826, Central Excise Act, 194427 and the CGST Act. The dissenting opinion of Subba Rao, J. in Barkat Ram28 is also relied upon. Thereafter, it is stated that PMLA, being a purely penal statute, one needs to look at the Statement of Objects and Reasons of the 1999 Bill and the Financial Action Task Force29 recommendations. 25 For short, “1861 Act” 26 For short, “1878 Act” or “the Sea Customs Act” 27 For short, “1944 Act” or “the Central Excise Act” 28 Supra at Footnote No.24 29 For short, “FATF” – an inter-governmental body, which is the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog.

- 36. 36 (xiv) Reliance was also placed on Raja Ram Jaiswal vs. State of Bihar30 . Further, it has been stated that even in Tofan Singh vs. State of Tamil Nadu31, the case of Raja Ram Jaiswal32 has been relied upon and it is concluded that when a person is vested with the powers of investigation, he is said to be a police officer, as he prevents and detects crime. Further, the powers under Section 50 of the PMLA for the purpose of investigation are in consonance with what has been held in Tofan Singh33 and establishes a direct relationship with the prohibition under Section 25 of the 1872 Act. Another crucial point raised is that most statutes where officers have not passed the muster of ‘police officers’ in the eyes of law, contain the term “enquiry” in contrast with the term “investigation” used in Section 50 of the PMLA. A parallel has also been drawn between the definition of “investigation” under the PMLA in Section 2(1)(na) and Section 2(h) of the Cr.P.C. Further, it is urged that the test of power to file ‘chargesheet’ is not determinative of being a police officer. 30 AIR 1964 SC 828 31 2020 SCC OnLine SC 882 (Para 88) (also at Footnote No.24) 32 Supra at Footnote No.30 33 Supra at Footnote No.31 (also at Footnote No.24)

- 37. 37 (xv) It is then urged that Section 44(1)(b) of the PMLA stipulates that cognizance can be taken only on a complaint being made by the Authority under the PMLA. Whereas, in originally enacted Section 44(1)(b), both the conditions i.e., ‘filing of a police report’, as well as, ‘a complaint made by an authority’ were covered. Learned counsel also reminisces of the speech of the then Finance Minister on the Prevention of Money-Laundering (Amendment) Bill, 200534 in the Lok Sabha on 06.05.2005. However, it was also conceded that the amendment of Section 44(1)(b) of the PMLA removed the words, “upon perusal of police report of the facts which constitute an offence under this Act or”. Next amendment made was insertion of Section 45(1A) and Section 73(2)(ua), by which the right of police officers to investigate the offence under Section 3 was restricted unless authorised by the Central Government by way of a general or special authorisation. Further amendment was deletion of Section 45(1)(a) of the PMLA, making the offence of money-laundering under the PMLA a non-cognizable offence. Further, it is submitted that amendment to Section 44(1)(b) has been made as a consequence for 34 For short, “2005 Amendment Bill”

- 38. 38 making the offence under the PMLA non-cognizable. It is stated that even today if investigation is done by a police officer or another, he can only file a complaint and not a police report. Therefore, the above-mentioned test is irrelevant and inapplicable. Absurdity that arises is due to two investigations being conducted, one by a police officer and the other by the authorities specified under Section 48. An additional point has been raised that the difference between a complaint under the PMLA and a chargesheet under the Cr.P.C. is only a nomenclature norm and they are essentially the same thing. Thus, basing the determination of whether one is a police officer or not, on the nomenclature, is not proper. (xvi) In respect of interpretation and constitutionality of Section 50 of the PMLA, our attention is drawn to Section 50(2) which pertains to recording of statement of a person summoned during the course of an investigation. In that, Section 50(3) posits that such person needs to state the truth. Further, he has to sign such statement and suffer the consequences for incorrect version under Section 63(2)(b); and the threat of penalty under Section 63(2) or arrest under Section 19.

- 39. 39 (xvii) It is urged that in comparison to the constitutional law, the Cr.P.C. and the 1872 Act, the provisions under the PMLA are draconian and, thus, violative of Articles 20(3) and 21 of the Constitution. Our attention is drawn to Section 160 of the Cr.P.C. when person is summoned as a witness or under Section 41A as an accused or a suspect. In either case, the statement is recorded as per Section 161 of the Cr.P.C. Safeguards have been inserted by this Court in Nandini Satpathy vs. P.L. Dani & Anr.35, while also the protection under Section 161(2) is relied on. Thus, based on Sections 161 and 162, it is submitted that such evidence is inadmissible in the trial of an offence, unless it is used only for the purpose of contradiction as stipulated in Section 145 of the 1872 Act. Further, it is stated that proof of contradiction is materially different from and does not amount to the proof of the matter asserted36 and can only be used to cast doubt or discredit the testimony of the witness who is testifying before Court37. The legislative intent behind Section 162 of the Cr.P.C. is also relied 35 (1978) 2 SCC 424 36 Tahsildar Singh & Anr. vs. State of U.P., AIR 1959 SC 1012 (paras 16-17, 42); Also see: V.K. Mishra & Anr. vs. State of Uttarakhand & Anr., (2015) 9 SCC 588 (paras 15-20) 37 Somasundaram alias Somu vs. State represented by the Deputy Commissioner of Police, (2020) 7 SCC 722 (para 24)

- 40. 40 upon, as has been held in Tahsildar Singh & Anr. vs. State of U.P.38. (xviii) It is, therefore, urged that the current practice of the ED is such that it violates all these statutory and constitutional protections by implicating an accused by procuring signed statements under threat of legal penalty. The protection under Section 25 of the 1872 Act is also pressed into service. (xix) To make good the point, learned counsel proceeded to delineate the legislative history of Section 25 of the 1872 Act. He referred to the first report of the Law Commission of India and the Cr.P.C., which was based on gross abuse of power by police officers for extracting confessions.39 Further, this protection was transplanted into the 1872 Act40, where on the presumption that a confession made to a police officer was obtained through force or coercion was fortified41. It was pointed out that recommendations of three Law Commissions – 14th, 48th and 69th which advocated for allowance of 38 AIR 1959 SC 1012 (also at Footnote No.36) 39 185th Law Commission Report on the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 (2003) 40 See also: Barkat Ram (supra at Footnote No.24) 41 Balkishan A. Devidayal vs. State of Maharashtra, (1980) 4 SCC 600 (para 14)

- 41. 41 such confessions to be admissible, were vehemently rejected in the 185th Law Commission Report. Thus, relying on Raja Ram Jaiswal42 where a substantial link between Section 25 of the 1872 Act, police officer and confession has been settled. Therefore, the present situation where prosecution can be mounted under Section 63 for failing to give such confessions is said to be contrary to procedure established by law interlinked with the right to a fair trial under Article 21. Reliance has also been placed on Selvi & Ors. vs. State of Karnataka43, the 180th Law Commission Report and Section 313 of the Cr.P.C. as being subsidiaries of right against self- incrimination and right to silence, not being read against him. (xx) Learned counsel then delineated on the preconditions for protection of Article 20(3). First, the person standing in the character of an accused, as laid down in State of Bombay vs. Kathi Kalu Oghad44, has been referred to. In this regard, it is submitted that the term may be given a wide connotation and an inclusion in the FIR, ECIR, chargesheet or complaint is not necessary and can 42 Supra at Footnote No.30 43 (2010) 7 SCC 263 (paras 87-89) 44 AIR 1961 SC 1808

- 42. 42 be availed even by suspects at the time of interrogation. It is urged that both the position of law stands clarified in Nandini Satpathy45 and Selvi46 — even to the extent where answering certain questions can incriminate a person in other offences or where links are furnished in chain of evidence required for prosecution. It is then urged that the expression ‘shall be compelled’ is not restricted to physical state, but also mental state of mind and it is argued that nevertheless a broad interpretation must be given to the circumstances in which a person can be so compelled for recording of statement. Additionally, the term ‘to be a witness’ would take within its fold ‘to appear as a witness’ and it is said that it must encompass protection even outside Court in investigations conducted by authorities such as the ED47. It was also argued that this protection should extend beyond statements that are confession, such as incriminating statements which would furnish a link in the chain of evidence against the person. 45 Supra at Footnote No.35 46 Supra at Footnote No.43 47 M.P. Sharma & Ors. vs. Satish Chandra, District Magistrate, Delhi & Ors., (1954) SCR 1077 (para 10).

- 43. 43 (xxi) It is submitted that the test which this Court ought to consider for determination of the vires of Section 50 of the PMLA is: whether a police officer is in a position to compel a person to render a confession giving incriminating statement against himself under threat of legal sanction and arrest? It is further pointed out that the ED as a matter of course records statement even when the accused person is in custody. In some circumstances, a person is not even informed of the capacity in which he/she is being summoned. What makes it worse is the fact that the ED claims the non-application of Chapter XII of the Cr.P.C. It does not register FIR and keeps the ECIR as an internal document. All the above- mentioned circumstances are said to render the questioning by the ED, which might not be restricted to the offence of money-laundering alone, as a testimonial compulsion48 . Hence, advocating the protection of Article 20(3) of the Constitution, it is submitted that all safeguards and protections are rendered illusionary. (xxii) Finally, an argument is raised that Section 50 of the PMLA is much worse than Section 67 of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic 48 Even the applicability of Prevention of Money-Laundering (Forms, Search and Seizure or Freezing and the Manner of Forwarding the Reasons and Material to the Adjudicating Authority, Impounding and Custody of Records and the Period of Retention) Rules, 2005.

- 44. 44 Substance Act, 198549. Further, the NDPS Act is the underlying reason for the PMLA and this Court in Tofan Singh50, in no uncertain terms, has given protection in respect of confessional statement even in the NDPS Act. The much harder and harsher punishment of death in the NDPS Act is also contrasted against the PMLA. It is also submitted that constitutional safeguards cannot be undermined by the usage of the term ‘judicial proceedings’. The term has been defined in Section 2(i) of the Cr.P.C. which includes any proceeding in the course of which evidence is or may be legally ‘taken on oath’51. Section 50(1) has been distinguished for being in respect of only Section 13 of the PMLA. It is also submitted that the enforcement authority is not deemed to be a civil Court; it can be easily concluded that an investigation done by the enforcement authority is not a judicial proceeding and Section 50 of the PMLA falls foul of the constitutional safeguards. (xxiii) Pertinently, arguments have also been advanced in respect of the implication of laws relating to money bills and their 49 For short, “NDPS Act” 50 Supra at Footnote No.31 (also at Footnote No.24) 51 Assistant Collector of Central Excise, Guntur vs. Ramdev Tobacco Company, (1991) 2 SCC 119 (para 6)

- 45. 45 application to the Amendment Acts to the PMLA. However, at the outset, we had mentioned that this issue is not a part of the ongoing discourse in this matter and we refrain from referring to the arguments raised in that regard. 3. Next submissions were advanced by Mr. Sidharth Luthra, learned senior counsel on the same lines. He argued that the current procedure envisaged under the PMLA is violative of Article 21 of the Constitution of India. The procedure established by law has to be in the form of a statute or delegated legislation and pass the muster of the constitutional protections.52 The Cr.P.C. has several safeguards in respect of arrested investigation; they are also rooted in the Cr.P.C. of 1898. They are reflective of the constitutional protections. The manual, circulars, guidelines of the ED are executive in nature and as such, cannot be used for the curtailment of an individual liberty. Under the PMLA, there is no visible sign of these protections against police's power of search and arrest; it is in stark contrast with the constitutional protections given also the 52 Gudikanti Narasimhulu & Ors. vs. Public Prosecutor, High Court of Andhra Pradesh, (1978) 1 SCC 240 (paras 1, 2, 10)

- 46. 46 reverse presumption against innocence at stage of bail under Section 45 of the PMLA. Further, the destruction of the presumption of innocence under Sections 22, 23 and 45 cannot even meet the test at the pre-complaint and pre-cognizance stage53 and the accused cannot escape the rigors of custody as per Section 167 of the Cr.P.C. As such, these conditions of reverse burden are in violation of Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. Presumption of innocence even in the pre-constitutional era has been a part of the right to a fair trial.54 After the Constitution came into existence, it has formed a part of a human right and procedure established by law.55 Lack of oversight in an investigation under the PMLA is said to be in gross violation of justice, fairness and reasonableness. It is also pointed out that while the predicate offence might be investigated, protected under the garb of the Cr.P.C., the non-application of such safeguards under the PMLA is wholly unjustified.56 The procedure as envisaged under the PMLA, especially under Section 17, vests the 53 Ranjitsing Brahmajeetsing Sharma vs. State of Maharashtra & Anr., (2005) 5 SCC 294 (paras 10, 11 and 21). 54 Attygalle & Anr. vs. The King, AIR 1936 PC 169 55 Noor Aga vs. State of Punjab & Anr., (2008) 16 SCC 417 56 State of West Bengal & Ors. vs. Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights, West Bengal & Ors., (2010) 3 SCC 571 (Para 68)

- 47. 47 executive with the supervisory power in an investigation. The same is anathema to the rule of law and the magisterial supervision of an investigation is an integral part and is a necessity for ensuring free and fair investigation.57 (i) It is further submitted that not supplying of the ECIR to the accused is in gross violation of Article 21 of the Constitution, the ECIR being equivalent to an FIR instituted by the ED. It contains the grounds of arrest, details of the offences; and as such, without the knowledge of the ingredients of such a document the ability of the accused to defend himself at the stage of bail cannot be fully realized. It may also hamper the ability to prepare for the trial at a later stage58 . Further, it is submitted that even under the 1962 Act and the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, 197359, Section 167 of the Cr.P.C. has been held to be applicable and also found to be a human right60 . Further, it is argued that there is no rational basis for a search or a seizure to be reported to the Adjudicating Authority, 57 Sakiri Vasu vs. State of Uttar Pradesh & Ors., (2008) 2 SCC 409 (paras 15-17) 58 Youth Bar Association of India (supra at Footnote No.11); Also see: D.K. Basu vs. State of W.B., (1997) 1 SCC 416 59 For short, “FERA” 60 Directorate of Enforcement vs. Deepak Mahajan & Anr., (1994) 3 SCC 440

- 48. 48 as they have no control. Further, the PMLA has two sets of processes for attachment and confiscation which is subject to final determination. Hence, lack of judicial oversight is irrational, as attachment is a step-in aid for final adjudication. In absence of safeguards and supply of ECIR, a fair investigation is not a statutory obligation. This is contrary to the Constitution and the Cr.P.C. Further, it is submitted that personal liberty under Article 21 cannot be curtailed as the ED manuals, circulars and guidelines are administrative directions and cannot be regarded as law under Article 13 of the Constitution. Such restrictions on personal liberty based on administrative directions are neither reasonable restrictions nor law under Articles 13 and 19(2) of the Constitution. Reliance has been placed on a plethora of cases, such as Bidi Supply Co. vs. Union of India & Ors.61 , Collector of Malabar & Anr. vs. Erimmal Ebrahim Hajee62 , G.J. Fernandes vs. The State of Mysore & Ors.63 and Bijoe Emmanuel & Ors. vs. State of 61 AIR 1956 SC 479 (para 9) 62 AIR 1957 SC 688 (paras 8,9) 63 AIR 1967 SC 1753 (para 12)

- 49. 49 Kerala & Ors.64 to show that the inapplicability of Chapter XII of the Cr.P.C. cannot be countenanced. (ii) It is also argued that the PMLA has inadequate safeguards for guaranteeing a fair investigation. For, there are no safeguards akin to Sections 41 to 41D, 46, 49, 50, 51, 55, 55A, 58, 60A of the Cr.P.C. Under Chapters V and VII of the PMLA, safeguards are limited to Sections 16 to 19 and 50. The onerous bail conditions under Section 45 are in the nature of jurisdiction of suspicion that is preventive detention under Article 22(3) to 22(7), which in itself has various safeguards which are absent in the PMLA. Further, post 2019 amendment, making money-laundering a cognizable and non- bailable offence, there are no more checks and balances present against the exercise of discretion by the ED. Magisterial oversight has been revoked; also, supervision envisaged under Section 17 is that of the executive which is against the rule of law and right of fair trial65. It is also stated that under the current scheme, an accused will be subject to two different procedures which is under the predicate offence and under the PMLA. To illustrate, Sections 410 64 (1986) 3 SCC 615 (paras 9, 10, 13-19) 65 Sakiri Vasu (supra at Footnote No.57) (paras 15-17)

- 50. 50 and 411 of the IPC are scheduled offences overlapping with Sections 3 and 4 of the PMLA. However, the safeguards provided are nowhere uniform. The same is unreasonable and manifestly arbitrary66 . It is also to be noted that the PMLA does not expressly exclude the application of Chapter XII of the Cr.P.C. and as such, ambiguity must be interpreted in a way that protects fundamental rights of the people67 . (iii) The next leg of the argument is to the effect that subsequent amendment cannot revive Section 45, which was struck down as unconstitutional by the decision in Nikesh Tarachand Shah68. The same could have not been revived by the 2018 and 2019 amendments. A provision or a statute held to be unconstitutional must be considered stillborn and void, and it cannot be brought back to life by a subsequent amendment that seeks to remove the constitutional objection. It must be imperatively re-enacted69 . Further, even in arguendo, the twin conditions are manifestly 66 Subramanian Swamy vs. Director, Central Bureau of Investigation & Anr., (2014) 8 SCC 682 (paras 49, 70). 67 Tofan Singh (supra at Footnote Nos. 24 and 31) (para 4.10) 68 Supra at Footnote No.3 69 Saghir Ahmad vs. State of U.P. & Ors., AIR 1954 SC 728 (para 23); Also see: Deep Chand vs. The State of Uttar Pradesh & Ors., (1959) Supp. 2 SCR 8 (para 21)

- 51. 51 arbitrary as it is against the basic criminal law jurisprudence of the right of presumption of innocence. This right has been recognized under International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights70 , as well as, by this Court in Babu vs. State of Kerala71. It is also contended that subjecting an accused person not arrested during investigation to onerous bail conditions under Section 45 is contrary to the decision of this Court72 . It was urged that even other statutes have such twin conditions for bail such as Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 198773 , the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act, 199974 and the NDPS Act. However, it is pointed out that it has been held that such onerous conditions were necessary only in certain kinds of cases - for example, terrorist offences, which are clearly a distinct and incompatible offence in the face of PMLA. Further, it is argued that even under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 196775 , the Court has to examine only 70 For short, “ICCPR” 71(2010) 9 SCC 189 (paras 27 and 28) 72 Satender Kumar Antil vs. Central Bureau of Investigation & Anr., (2021) 10 SCC 773 and clarificatory order dated 16.12.2021 in MA No. 1849/2021 73 For short, “TADA Act” 74 For short, “MCOCA” 75 For short, “UAPA”

- 52. 52 whether the allegation is prima facie true while granting bail, but in case of PMLA, the Court has to reach a finding that there are reasonable grounds for believing that the accused is not guilty before granting bail. Thus, as soon as charges are framed, a person is disentitled to apply for bail as prima facie case is made out, which helps in achieving the purpose of preventive detention without procedure established by law76 . Further, these deep restrictive conditions even under the UAPA and the NDPS Act are restricted only to parts of these Acts and not to the whole of them. However, the same is not the case under the PMLA, as it is applicable to all predicate offences. Such an approach ignores crucial distinctions such as nature, gravity and punishment of different offences in the Schedule of PMLA and treats unequals as equals. This is in violation of Article 14 of the Constitution of India. Reliance is also placed on United States vs. Anthony Salerno77, where restrictive bail provisions are permitted in pre-trial detention because of the presence of detailed procedural safeguards. Still, it is argued, that such restrictive bail provisions cannot oust the ability of 76 Ayya alias Ayub vs. State of U.P. & Anr., (1989) 1 SCC 374 (paras 11-17) 77 107 S.Ct. 2095 (1987)

- 53. 53 Constitutional Court to grant bail on the ground of violation of Part III of the Constitution78 . Further, it has been held that Magistrate must ensure that frivolous prosecution is weeded out. Provisions such as Sections 21, 22, 23 and 45 of the PMLA reverse the burden and curtail the jurisdiction of the trial Court arbitrarily in violation of the findings of this Court79 . Thus, various counts that have been argued herein point out that the PMLA suffers from manifest arbitrariness in light of Shayara Bano vs. Union of India & Ors.80 and Joseph Shine vs. Union of India81 . 4. Next in line for submissions on behalf of private parties is Dr. Abhishek Manu Singhvi, learned senior counsel. He firstly argued the point of burden of proof under Section 24 of the PMLA. He has pointed out that prior to amendment, the entire burden of proof right from investigation till the judgment was on the accused. Even though this has changed post 2013 amendment and some balance has been restored, it has not fully cured this section of its 78 Union of India vs. K.A. Najeeb, (2021) 3 SCC 713 : 2021 SCC Online SC 50 (para 18) 79 Krishna Lal Chawla & Ors. vs. State of Uttar Pradesh & Anr., (2021) 5 SCC 435 80 (2017) 9 SCC 1 (paras 87, 101) 81 (2019) 3 SCC 39 (paras 61, 103, 105)

- 54. 54 unconstitutional nature. He has gone into the legislative history of the Act and stated that originally the presumption was raised even prior to the trial and state of charge, this was diluted by the amendment of 2013 thereafter the presumption would only apply after the framing of charges. (i) Learned senior counsel submits that the wording of Section 24 refers to formal framing of charges under Section 211 of the Cr.P.C. For this submission, he relies on the speech of the Minister introducing the amendment in the Parliament. It has been stated that presumption is raised in relation to the fact of money- laundering. Such a presumption cannot be raised in relation to an essential ingredient of an offence. The commission of an offence, as such, cannot be presumed. In reference to Section 4 of the 1872 Act, distinction between sub-sections (a) and (b) of Section 24 is highlighted, wherein the former states - ‘shall presume’ and the latter states - ‘may presume’. (ii) It is urged that post amendment also there is no requirement for the prosecution to prove any facts once the charges are framed. The entire burden of disproving the case, as set out in the complaint, inverts onto the accused. It is, hence, contrary to the requirement

- 55. 55 of proof of foundational facts, as is seen in other legislations. Such an inversion is not present in any other statute. It is stated that even in the NDPS Act, where no requirement of foundational facts was provided, this Court has read such necessity into the Act. As for sub-section (b), it is pointed out that the ‘may presume’ provision eliminates the safeguards of sub-section (a) and provides no guidance as to when a presumption is to be invoked. The learned counsel also points the discrepancy that the word ‘authority’ appearing in Section 24, which also appears in Section 48, is distinctive in nature and that Section 24 absurdly allows an investigator to presume the commission of an offence. This is clearly arbitrary and de hors logic. In light of the same, the constitutional vires of the section are challenged or a reading down to fulfil the constitutional mandate is pressed for. (iii) The next point of attack for Dr. Singhvi, learned senior counsel is the constitutionality of Sections 17 and 18. The absence of safeguards in lieu of searches and seizures is canvassed. It has been pointed out that such searches or seizures can take place even without an FIR having been registered or a complaint being filed before a competent Court. Foremost, the legislative history of these

- 56. 56 two Sections is pointed out. It is shown that originally the search and seizure was to be conducted after the filing of a chargesheet or complaint in the predicate offence. Thereafter, the protection was diluted by the 2009 amendment, wherein it was provided that the search and seizure operations would take place only after forwarding a report to the Magistrate under Section 157 of the Cr.P.C. It was only in 2019 that these final safeguards were also completely removed by the Finance (No. 2) Act, 2019. The effect, it is argued, is such that the ED has unfettered powers to commit searches and seizures without any investigation having been done in the predicate offence, and sometimes even without an FIR being registered. There are no prerequisites or safeguards as the ED can now simply walk into a premises. Even for non-cognizable offences, the ED need not wait for the filing of a complaint before a Court. In this way, in the absence of any credible information to investigate, the ED cannot be allowed to use such uncanalized power. The magisterial oversight cannot be replaced by the limited oversight of the Adjudicating Authority, as they have no real control over the ED, especially in case of criminal investigations. Thus, it is submitted that such lack

- 57. 57 of effective checks and balances is unreasonable and violative of Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. (iv) Our attention is also drawn to the Prevention of Money- Laundering (Forms, Search and Seizure or Freezing and the Manner of Forwarding the Reasons and Material to the Adjudicating Authority, Impounding and Custody of Records and the Period of Retention) Rules, 200582, and it is prayed that this Court must clarify that these rules are not ultra vires Sections 17 and 18 of the PMLA. Pertinently, they relate to the provisions of Cr.P.C. being applicable to searches under the Act. (v) Next leg of submissions challenges the vires of the second proviso of Section 5(1), as it allows for attachment independent of the existence of a predicate offence, given that such property might not even be proceeds of crime. Though an emergency procedure, no threshold had to be met and the first proviso has no application. It is also submitted that the proviso cannot travel beyond the scope of the main provision. Our attention is drawn to the legislative history; it is stated that the PMLA did not originally contain the second 82 For short, “Seizure Rules, 2005”

- 58. 58 proviso. Attachment was only to be done after filing of chargesheet in the predicate offence. For the first time, in 2009, this proviso was added, to avoid frustration of the proceedings. It is submitted that this proviso has no anchor to either the scheduled offence or the proceeds of crime. It is at the mere satisfaction of the officer. In this way, it is submitted, attachment of property of any person can be made, with no fetters. Our attention is also drawn to the use of word ‘any’ for person and property and its distinction from the term ‘proceeds of crime’, having a direct nexus with the ambit of the main Section. It is argued that it is not to be mixed with any offence but only scheduled offences. The ED is alleged to employ this language in attaching property purchased much before the commission of scheduled offences, to the extent not having any nexus. It is submitted that there has to be a link between the second proviso to the proceeds of crime and scheduled offence being investigated under a specific ECIR before the ED.83 (vi) Submissions with respect to Section 8 of the PMLA maintain that Section 8(4) allows the ED to take possession of the attached 83 Dwarka Prasad vs. Dwarka Das Saraf, (1976) 1 SCC 128, Also see: Satnam Singh & Ors. vs. Punjab & Haryana High Court and Ors., (1997) 3 SCC 353

- 59. 59 property at the stage of confirmation of provisional attachment made by the Adjudicating Authority. It is submitted that this deprivation of a person’s right to property at such an early stage without the due process of law, is unconstitutional. Further the period of attachment under Section 8(3)(a) of the PMLA is also arbitrary and unreasonable. To make good the point, the relevant legislative history is pointed out. The original enactment where provisional attachment would continue during the pendency of proceedings related to ‘any scheduled offence’. Thereafter in 2012, the same was changed to ‘any offence under the PMLA’, followed by 2018 amendment – ‘a period of ninety days during investigation of the offence or during pendency of proceedings under the PMLA’, and finally by 2019 amendment the increase from ‘ninety days’ to ‘three hundred and sixty-five days’. We are also taken through the elaborate process of attachment of property. Thereby, it is highlighted that the ED can take possession of property after a single adjudicatory process, wherein there is no oversight over the ED. It is stated that such alienation of property without any proceedings having been brought before the Court is undoubtedly an unconstitutional act. As for Section 8(3)(a) clarification is sought in

- 60. 60 light of the confusion that it allows for a continuation of the confirmed provisional attachment for three hundred and sixty-five days or during the pendency of proceedings under the PMLA. This might lead to a reading where the ED has a period of three hundred and sixty-five days to file its complaint. (vii) Learned counsel then referred to the Prevention of Money- Laundering (Taking Possession of Attached or Frozen Properties Confirmed by the Adjudicating Authority) Rules, 201384 wherein specific challenge is raised against Rules 4(4), 5(3), 5(4) and 5(6). The main ground of challenge is disproportionality, similar to the attachment issue, transfer of attached shares and mutual funds, depressing of value of property, eviction of owners of a movable property, possession of productive assets along with gross income, all monetary benefit is stated to be arbitrary, reasonable, absurd and disproportionate. Herein, it is highlighted that various anomalies may crop up, such as taking of the shares and the ED becoming the majority shareholder in corporations, attachment of properties worth far more than the value of proceeds of crime. Under Section 84 For short, “Taking Possession Rules, 2013”

- 61. 61 2(1)(zb), the expression “value” is defined as fair market value on the date of acquisition and not fair market value on date of attachment. Arguably, property bought years ago is thereby undervalued by the ED. Attachment of immovable property and eviction in case of unregistered leases is also challenged. To challenge this disproportionate imposition and restrictions, reliance is placed on Shayara Bano85 and Anuradha Bhasin vs. Union of India & Ors.86 . (viii) It is then urged by the learned counsel that Section 45(1) of the PMLA, reverses the presumption of innocence at the stage of bail as an accused. According to him, the accused at this stage can never show that he is not guilty. It is also maintained that these are disproportionate and excessive conditions for a bail. Reference is also made to Nikesh Tarachand Shah87 to the limited extent that the 2018 amendment has not removed invalidity, pointed out in the aforesaid judgment of this Court. It is also stated that regardless of the amendment, the twin condition is in violation of Article 21 of the 85 Supra at Footnote No.80 (paras 101-102) 86 2020 (3) SCC 637 87 Supra at Footnote No.3

- 62. 62 Constitution by virtue of the nature of the offence under PMLA. It is stated that presumption of innocence is a cardinal principle of Indian criminal jurisprudence.88 Reference is also made to Kiran Prakash Kulkarni vs. The Enforcement Directorate and Anr.89 Arguments have also been raised against an amendment through a Money Bill being violative of Article 110 of the Constitution. The need for interpretation by Rojer Mathew vs. South Indian Bank Limited and Ors.90 has also been asserted. The 2018 amendment is also challenged by referring to the notes on Clauses of the Finance Bill, 2018. It is also pointed out that similar amendments were proposed for the 1962 Act in the year 2012 and, yet, the same were dropped at the insistence of members of the Parliament91 . (ix) Further, given the maximum punishment of seven (7) years under PMLA, it was argued that it is disproportionate when comparing the same to other offences under the IPC which are far more serious in nature and are punishable with death. In light of the same, it is highly questionable as to how such an onerous 88 Arnab Manoranjan Goswami vs. State of Maharashtra & Ors., (2021) 2 SCC 427 (para 70) 89 Order dated 11.4.2019 in S.L.P. (Criminal) No.1698 of 2019 90 (2020) 6 SCC 1 91 Speech of Shri. Arun Jaitley dated 26.3.2012 in the Rajya Sabha

- 63. 63 condition can be imposed on an accused. It is also pointed out that several scheduled offences are bailable. Further, the anomaly that at the time of arrest under Section 19 no documents are provided in certain cases, has also been highlighted. It was also stated that it is a near impossibility to get bail as under the UAPA, TADA Act, or the Prevention of Terrorism Act, 200292. 5. Mr. Mukul Rohatgi, learned senior counsel was next to argue on behalf of private parties. He urged that the Explanation to Section 44 is contrary to Section 3 read with Section 2(1)(u), hence, the same is unsustainable and arbitrary in the eyes of law. Special emphasis was laid on the expression “shall not be dependent upon any order by the Trial Court in the scheduled offence”. It was argued that both trials may be tried by the same Court. In such a case, Section 3 offence cannot be given pre-eminence, as that would run contrary to Section 3 and would be manifestly arbitrary, given the fact that an acquittal in the scheduled offence cannot lead to one being found guilty for the derivative offence of money-laundering. A direct link between the proceeds of crime and Section 3 offence was also 92 For short, “POTA”

- 64. 64 highlighted. It was submitted that the Special Court cannot continue with the trial for Section 3 offence once acquittal in the predicate offence takes place. Section 44 unmistakably provides for the Special Court trial of money-laundering. It was pointed out that it is normal that if one is acquitted for the predicate offence, the money-laundering procedure could still go on. This is contrary to the definition under Section 3, which states that money-laundering is inextricably linked to the predicate offence. (i) It was also pointed out that the usual practice is of filing an ECIR on the same day or right after the FIR has been filed by replicating it almost verbatim. Canvassing for proper procedure and investigation before filing of the ECIR and initiation of the process under the PMLA, reference was also made to other Acts, such as Smugglers and Foreign Exchange Manipulators Act, 197693, FERA or Conservation of Foreign Exchange and Prevention of Smuggling Activities Act, 197494 and the 1962 Act, being Acts which would not subsist alone or by themselves without the predicate offences95 . 93 For short, “SAFEMA” 94 For short, “COFEPOSA” 95 Barendra Kumar Ghosh vs. The King Emperor, 1924 SCC OnLine PC 49 : AIR 1925 PC 1

- 65. 65 (ii) It was also argued that often the ED widens the investigation beyond what is contained in the chargesheet. This is contrary to the intentions of the Act. The true meaning of the definition under Section 3 of the PMLA was proposed to be divided into three components of predicate offence, proceeds of crime and projecting/claiming as untainted. It was conceded that even abetment would form a part of the offence and as a consequence, whoever attempts, assists, abets, incites - are all covered by the same. For predicate offence and Section 3, it was stated that if the former is gone, the latter cannot subsist. (iii) Next argument raised pertained to the ambit and meaning of Section 3. It was submitted that mere possession or concealment of proceeds of crime will not constitute money-laundering and this was bolstered by the phrase ‘projecting or claiming as untainted property’. The “and” was stated to be a watertight compartment. The Finance Minister’s 2012 Rajya Sabha Speech was also relied upon to showcase how “and projecting” was an essential element. 6. Mr. Amit Desai, learned senior counsel also advanced submissions on behalf of private parties. He also took us through

- 66. 66 the history of money-laundering, starting from the Conventions to the FATF and UN General Assembly Resolution96 , which led to the 1999 Bill to help combat and prevent money-laundering. He relies on the Statement of Objects and Reasons of the Act97 , followed by the initial ambit of Sections 2(1)(p), 2(1)(u) and 3, which were amended by the 2013 amendment. It is stated that the Act presupposes the commission of a crime which is the predicate offence; hence the questions to be answered by this Court are related to retrospectivity. Firstly - whether authorities can proceed against an accused when commission of the predicate offence predates the addition of the said offences to the Schedule of the PMLA? Secondly - whether the authorities can proceed against the properties obtained or projected prior to the commission of an offence under this Act? Thirdly - whether authorities can proceed when the predicate offence and the projecting predate the commencement of this Act? Fourthly - whether jurisdiction subsists under the Act 96 Special Session of the United Nations held for 'Countering World Drug Problem Together' held in June 1998. 97 “objective was to enact a comprehensive legislation inter alia for preventing money laundering and connected activities confiscation of proceeds of crime, setting up of agencies and mechanisms for coordinating measures for combating money-laundering, etc”. It was also indicated that the proposed Act was “an Act to prevent money-laundering and to provide for confiscation of property derived from, or involved in, money-laundering and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto”.

- 67. 67 when no cognizance has been taken, the accused has been discharged or acquitted or the offence compounded? Lastly, learned counsel also challenges the rigors of the twin conditions for being incongruent with general bail provisions under Sections 437 and 439 of the Cr.P.C. as being ultra vires. (i) Learned counsel refers to one of the cases in this batch, wherein the properties sought to be acquired by the ED were obtained by the petitioner prior to 2009, while the commission of offence was in 2013 and Section 13 of the PC Act was inserted into the PMLA Schedule for the first time in 2009. This, it is maintained cannot fit into the term “proceeds of crime” under Section 2(1)(u), the same having been done prior to 2009. It has also been submitted that for the determination of money-laundering under Section 3 or any other provision of the Act, the relevant time has to be the time of the commission of the scheduled offence. The rationale being that only the presence of a scheduled offence can lead to the generation of proceeds of crime and, hence, in return the offence of money- laundering can be committed. Thus, in a way it is suggested that the starting point for a conviction for Section 3 might be the commission of a scheduled offence. The argument in respect of the

- 68. 68 protections provided by the Constitution under Article 20(1), as per which ingredients for an offence must exist on the day the crime is committed or detected, have also been impressed in opposition of any retrospective or retroactive application of the Act. To bolster the arguments, reliance has been placed on the decisions of this Court in Soni Devrajbhai Babubhai vs. State of Gujarat and Ors.98 , Mahipal Singh vs. Central Bureau of Investigation & Anr.99 , Tech Mahindra Limited vs. Joint Director, Directorate of Enforcement, Hyderabad & Ors.100 , and Gadi Nagavekata Satyanarayana vs. Deputy Director Directorate of Enforcement101 and that of Delhi High Court in Arun Kumar Mishra vs. Directorate of Enforcement102 , M/s. Ajanta Merchants Pvt. Ltd. vs. Directorate of Enforcement103 and M/s. Mahanivesh Oils & Foods Pvt. Ltd. vs. Directorate of Enforcement104 . 98 (1991) 4 SCC 298 (also at Footnote No.131) 99 (2014) 11 SCC 282 100 WP No. 17525/2014 decided on 22.12.2014 by High Court of Andhra Pradesh 101 2017 SCC Online ATPMLA 2 102 2015 SCC OnLine Del 8658 103 2015 SCC OnLine Del 8659. The decision was assailed by ED before this Court in SLP (Crl.) No. 18478/2015, wherein an order of Status-quo came to be passed. 104 2016 SCC OnLine Del 475. The judgement however was challenged by ED in LPA before the Division Bench wherein it was held that the same shall not be treated as precedent.

- 69. 69 (ii) The argument that to qualify for the offence of money- laundering, the essential ingredient of ‘projection’ or ‘claiming’ it as ‘untainted property’ is imperative, has also been pressed into service. It is also urged that proceeds of crime can only be generated from the commission of a predicate offence and the commencement of investigation arises only if a predicate offence has generated such proceeds of crime only subsequent to the inclusion of the predicate offence to the Schedule of the PMLA. Another point that has been highlighted is that the projecting, if done prior to the date of inclusion of the offence to the Schedule, the same cannot be continuing and as such, is stated to be stillborn for the purposes of the PMLA. (iii) It is urged that for the purposes of bail, it is settled law that offences punishable for less than seven years allows a person to be set free on bail. As such, the liberty as enunciated by Article 21 of the Constitution cannot be defeated by such an Act. Thus, Section 45(2) of the PMLA is contrary to general principles of bail and the Constitution of India. It is also pointed out that Section 437 of the Cr.P.C. imposing similar conditions as Section 45(2) restricts it to offences punishable with either life imprisonment or death.

- 70. 70 Under no condition can it be said that the bail conditions under the PMLA, imposing maximum seven years, are reasonable. Without prejudice to the aforementioned argument, it was stated that Section 45(2) could only be applicable to bail applications before the Special Court and the special powers under Section 439 Cr.P.C. It was submitted that in light of the same, special powers be given to the Special Court under the PMLA, as these provisions, draconian in nature, were contemplated only in Acts, such as TADA Act, POTA, MCOCA & NDPS Act, since securing the presence was difficult in all of the above. Further, unless Section 3 was to be restricted to organised crime syndicate, which was in fact the real intent, the bail provisions are liable to be struck down. 7. Mr. S. Niranjan Reddy, learned senior counsel contends that it is essential to first understand as to whether money-laundering is a standalone offence or dependent on the scheduled offence? He points out that the ED has maintained the former stance. It has been pointed out that this view has been rejected by the High Courts of Delhi, Allahabad and Telangana. On the contrary, the High Courts of Madras and Bombay have accepted such a view. It has

- 71. 71 been added that the ED's contention is based on the Explanation added to Section 44(1)(d) by the 2019 amendment. Concededly, though there are certain exemptions in Section 8(7), it is contended, that the same are only for special circumstances. Learned counsel then refers to the sequence of conducting the matters and points out Sections 43(2) and 44(1), whereby the Special Court can try the scheduled offence, as well as, the money-laundering offence. He points out that due to different findings of different High Courts, certain questions have arisen as to the sequence of conducting the said two cases. The High Courts of Jharkhand and Kerala have taken a view that both matters can be tried simultaneously; there is no necessity to hold back the trial of money-laundering until the scheduled offence has been tried. It has been submitted that the High Court of Kerala finds that the offence of money-laundering is dependent on the scheduled offence. The High Court for the State Telangana, on the other hand, finds money-laundering completely independent of the scheduled offence. To drive the point home, attention is drawn towards Section 212 of the IPC, where the High Courts have taken a view that unless the original offence is proved, the person harbouring the accused cannot be sentenced. However,