PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES ps.psychiatryonline.org September 201.docx

- 1. PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES � ps.psychiatryonline.org � September 2012 Vol. 63 No. 9 885555 Soldiers returning from combatoften face a postdeployment pe- riod in which there is an in- creased risk of readjustment stres- sors, such as problems with family, marriage, or employment. This peri- od can also be marked by the onset of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Coping with the additional burden of PTSD likely complicates soldiers’ ability to cope during the readjust- ment period. Accordingly, research has documented a relationship be- tween PTSD and greater readjust- ment stress among soldiers serving in recent conflicts (1) or in previous ones (2,3). Many soldiers with a mental health need do not seek care within the first year of their readjustment period. An estimated 23%–44% of returning sol- diers with PTSD or other mental health problems receive treatment within the first year (4,5). Linking re- turning soldiers who have PTSD with treatment is a national priority be- cause effective treatments for PTSD

- 2. are available (6,7) and PTSD suffer- ers who seek treatment experience symptom relief more quickly than those who do not (8). Therefore, re- search is needed to better understand the process by which returning sol- diers with PTSD seek treatment. Readjustment stressors may be a key motivator for treatment seeking. Veterans returning from Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) often seek help for fi- nancial, occupational, and other read- justment concerns. A qualitative study suggested that returning sol- diers are most likely to seek mental health treatment when problems emerge within family and occupa- tional roles (9). Accordingly, one study showed that combat veterans seeking care from the U.S. Depart- ment of Veterans Affairs (VA) ex- pressed most interest for services re- lated to veterans’ benefits (83%) and schooling, employment, or job train- ing (80%) (1). Also, at least one study Readjustment Stressors and Early Mental Health Treatment Seeking by Returning National Guard Soldiers With PTSD AAlleejjaannddrroo IInntteerriiaann,, PPhh..DD.. AAnnnnaa KKlliinnee,, PPhh..DD.. LLaannoorraa CCaallllaahhaann,, MM..SS.. MMiikkllooss LLoossoonncczzyy,, MM..DD..,, PPhh..DD..

- 3. Dr. Interian, Dr. Kline, and Dr. Losonczy are affiliated with the Department of Psychia- try, UMDNJ–Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, 671 Hoes Lane, D306, Piscataway, NJ 08854-5635 (e-mail: [email protected]). They are also with the Veterans Af- fairs New Jersey Healthcare System, Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences, Lyons, New Jersey. Ms. Callahan is with the Bloustein Center for Survey Research, Rutgers Univer- sity, Piscataway. Objectives: Readjustment stressors are commonly encountered by vet- erans returning from combat operations and may help motivate treat- ment seeking for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The study ex- amined rates of readjustment stressors (marital, family, and employ- ment) and their relationship to early mental health treatment seeking among returning National Guard soldiers with PTSD. Methods: Partici- pants were 157 soldiers who were surveyed approximately three months after returning from combat operations in Iraq and scored positive on the PTSD Checklist (PCL). The survey asked soldiers about their expe- rience with nine readjustment stressors as well as their use of mental health care in the three months after returning. Results: Many read- justment stressors were common in this cohort, and most soldiers expe-

- 4. rienced at least one stressor (72%). Univariate analyses showed that readjustment stressors were related to higher rates of treatment seek- ing. These findings remained significant after multivariate analyses ad- justed for depression and PTSD severity but were no longer significant after adjustment for age and marital status. Conclusions: Readjustment stressors are common among soldiers returning from duty with PTSD and may be more predictive than PTSD symptom levels in treatment seeking. These effects appeared to be at least partially accounted for by demographic variables and the role of greater familial and occupation- al responsibilities among older veterans. Treatment seeking may be mo- tivated by social encouragement or social interference and less by symp- tom severity. (Psychiatric Services 63:855–861, 2012; doi: 10.1176/appi. ps.201100337) has found a positive association be- tween mental health treatment seek- ing and readjustment stress (5). How- ever, because the study examined the effect of readjustment stressors in a sample with and without mental dis- orders, it may be that readjustment stressors are more common among

- 5. veterans with a mental disorder. Less clear is whether these stressors differ- entiate PTSD sufferers who go on to seek treatment from those who do not. Therefore, research is needed that further establishes the role of read- justment stressors in treatment seek- ing among PTSD sufferers, especially given that those suffering from this disorder may be more likely to be af- fected by readjustment stress (1). Such information can be valuable in policy and program development. Consistent with this aim, this study examined the role of readjustment stress as a predictor of mental health care seeking among returning sol- diers with likely PTSD. We hypothe- sized that readjustment stressors are significantly related to seeking mental health care. This study built on the existing literature by using survey re- sponses obtained from members of the New Jersey National Guard (NJNG) during reintegration events after a one-year deployment to Iraq. The survey collected information from veterans who did and did not seek mental health care, both within the Veterans Health Administration and from community-based provi- ders. Also, our analyses considered only veterans who met criteria for likely PTSD, in order to identify fac-

- 6. tors associated with help seeking, giv- en the need for PTSD treatment. With this sample, we describe the prevalence of readjustment stressors, their relationship to depressive and PTSD symptoms, and their associa- tion with early mental health treat- ment seeking. Methods Participants With support from the New Jersey Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, we collected data anony- mously in September 2009 from 1,665 of 1,723 NJNG soldiers who were attending postdeployment rein- tegration events three months after returning from a 12-month tour in Iraq. Twenty-nine attendees at the reintegration did not complete the survey, and an additional 29 were ex- cluded because of poor data quality as judged by three independent raters, yielding a response rate of 97%. The sample was surveyed as part of a larger, longitudinal study as- sessing the mental and physical health effects of serving in the NJNG. This study focused on the 179 NJNG soldiers who met criteria, based on self-report, for PTSD at three months postdeployment. Data collection

- 7. Anonymous and self-administered surveys were distributed to all NJNG members attending the reintegration events, which were held on four days over two consecutive weekends. The surveys were administered to soldiers in groups of approximately 45–75. Participation was voluntary, and NJNG leadership was not aware of soldiers’ survey completion status. Soldiers received no monetary incen- tive for participation. All research procedures were approved by the Rutgers University and VA New Jer- sey Healthcare System Institutional Review Boards. Measures PTSD was assessed with the PTSD Checklist (PCL), which is a 17-item self-report scale (10,11). This study focused on respondents who pro- duced a positive PTSD score (≥50). This criterion has been used fre- quently in PTSD research, including studies with veterans (11,12), and has been shown to have adequate sensi- tivity and specificity with a PTSD di- agnosis based on a structured psychi- atric interview (13). We measured PTSD severity as a continuous vari- able based on the PCL score. Depression was assessed with the commonly used nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (14)

- 8. and analyzed as a continuous variable. Readjustment stressors were assessed with a nine-item scale that inquired, using the following stem, whether a number of stressors occurred: “Did any of the following things trouble you during your deployment to Iraq or after you returned home?” Items inquired about marriage, financial, and family problems. The items for this measure were developed on the basis of qualitative interviews that elicited common readjustment expe- riences among New Jersey National Guardsmen. Participants indicated yes or no to each stressor, yielding a score of 0–9, with acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=.76). Utilization of mental health care Questions about mental health serv- ice use inquired about visits that oc- curred since returning home (post- deployment). We first asked whether participants had a visit with a “men- tal health professional” for a “mental health problem.” Respondents were provided with examples of mental health professionals, such as psy- chologists, psychiatrists, social work- ers, and counselors. Responses were used to code for any mental health visit postdeployment. Second, par- ticipants were asked whether they received a “doctor’s prescription” for

- 9. antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers, or sedatives. A response of yes concerning any of these med- ications was used to code “pre- scribed a psychotropic postdeploy- ment.” Given that pharmacotherapy is often provided by non–mental health physicians (that is, primary care physicians), we defined any mental health visit postdeployment as either having a mental health visit postdeployment or receiving a pre- scription for a psychotropic postde- ployment. This was the study’s key outcome. Analyses All analyses were completed with SPSS, version 16.0. Because of a 17% missing value rate for the variables pertaining to mental health visits, a missing value analysis assessed whether the missing values were re- lated to age, gender, race-ethnicity, and marital status and produced a nonsignificant value of Little’s miss- ing completely at random test. This signified that the values were missing randomly, and 22 cases with missing values therefore were not analyzed. Analyses first described rates of mental health visits that had been PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES � ps.psychiatryonline.org � September 2012 Vol. 63 No. 9885566

- 10. made within three months postde- ployment. Next, chi square analyses examined whether demographic vari- ables were significantly different among those with or without any mental health visit postdeployment. Significant variables were later used as covariates in the multivariate analyses. Chi square analyses then compared whether those having a visit differed according to individual readjustment stressors, as well as cat- egories of cumulative number of stressors reported. Correlations were then generated to examine the rela- tionship between readjustment stres- sors with the PCL score (Spearman rho), where PCL scores were catego- rized into tertiles because of nonnor- mal score distributions. Also, a Pear- son correlation was generated be- tween readjustment stress and PHQ- 9 scores. The final analysis used hier- archical logistic regression to exam- ine the association between readjust- ment stress and any mental health visit after controlling for the relevant mental health and demographic characteristics. The independent variables were entered into the mod- el in three blocks. Block 1 included readjustment stress only. In block 2, we added the mental health variables

- 11. PTSD and depression. Block 3 in- cluded all of the above variables plus the statistically significant demo- graphic variables. Results A total of 179 (11%) respondents scored positive for PTSD, and our analyses focused on the 157 who did not have missing utilization data. The rates for several types of mental health visits are summarized in Table 1. Rates of treatment contact ranged from 23% to 36% for the three- month postdeployment period, de- pending on the type of contact. Most visits occurred with a mental health professional, and the medications most commonly prescribed were an- tidepressants and sedatives. Table 2 summarizes the rates of having any mental health visit post- deployment, according to demo- graphic characteristics. Having a mental health visit significantly dif- fered by age and marital status. Pair- wise comparisons showed that Na- tional Guard soldiers who had any mental health visit postdeployment were more likely to be married or liv- ing with a partner (χ2=10.5, df=1, p< .001) and separated, divorced, or widowed (χ2=11.5, df=1, p<.001), compared with those who were sin-

- 12. gle. Having a visit was also more like- ly among soldiers ages 26–39 (χ2=4.1, df=1, p<.05) and 40–70 (χ2=8.3, df= 1, p<.01), compared with those who were ages 17–25. Table 3 shows the relationship be- tween any mental health visit postde- ployment and PTSD severity, depres- sion, and each of the individual read- justment stressors. First, PTSD symptom severity was not significant- ly related to utilization of mental health services. In contrast, having a visit was associated with a higher PHQ-9 depression score (greater de- pression). Table 3 also shows that sig- nificant negative life events were not PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES � ps.psychiatryonline.org � September 2012 Vol. 63 No. 9 885577 TTaabbllee 11 Mental health care utilization by 157 National Guard veterans within three months postdeploymenta Care used postdeployment N % Mental health visit 51 34 Prescribed a psychotropic 41 23 Any mental health visit (for psychotherapy or prescription) 57 36 Type of medication prescribedb

- 13. Antidepressant 25 14 Mood stabilizer 9 5 Anxiolytic 13 7 Sedative 29 16 a Some denominators are below 157 because of missing values. b Soldiers may have received a prescription for more than one psychotropic. TTaabbllee 22 Demographic characteristics of 157 National Guard veterans who did or did not have a mental health visit within three months postdeploymenta Any mental health visit postdeployment No Yes All veterans Characteristic N % N % N % p Age .02 17–25 40 40 11 19 51 33 26–39 37 38 24 43 61 40 40–70 21 21 21 38 42 27 Race or ethnicityb White 36 36 24 42 60 38 .50 Black 28 28 12 22 40 26 .34 Hispanic 27 27 16 28 43 27 .89 Other 9 9 5 9 14 9 .96 Gender .42 Male 77 77 47 83 124 79 Female 23 23 10 18 33 21

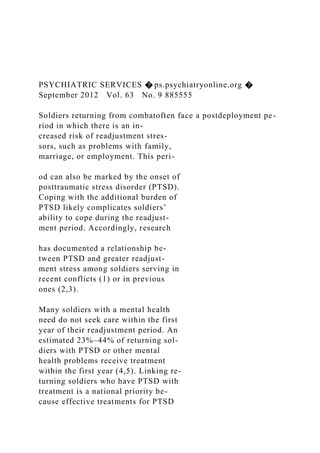

- 14. Marital status Married or living as married 32 32 28 50 60 39 <.001 Never married 56 57 14 25 70 45 Divorced, separated, or widowed 11 11 14 25 25 16 Education .77 High school or less 37 38 18 32 55 36 Some college 44 44 28 50 72 47 Bachelor’s degree or higher 18 18 10 18 28 18 a Some totals are below 157 because of missing values. b Analyses compared one racial or ethnic group with all others combined. uncommon in this group. Events as serious as job or business loss and marital separation or divorce were re- ported by 20% and 26% of the sam- ple, respectively. Illustrating a cumu- lative effect, higher levels of these readjustment stressors were signifi- cantly associated with having any mental health visit postdeployment (χ2=8.7, df=2, p≤.05) (Figure 1). In total, most soldiers experienced a readjustment stressor, with only 28% experiencing no stressors. Next, re- sults showed a significant number of readjustment stressors and a signifi- cant correlation between them and PCL score (analyzed in tertile cate-

- 15. gories; rs=.21, p≤.05) and PHQ-9 score (r=.26, p≤.001). Finally, Table 4 presents the results of multivariate models examining the prediction of any mental health visit postdeployment by level of readjust- ment stressors. Model 1 shows that National Guard soldiers with the highest accumulation of readjustment stressors were more likely to have any mental health visit postdeployment. Model 2 adjusted for the effects of PTSD symptom severity and depres- sion and found a mostly undimin- ished, statistically significant effect for readjustment stressors. This step shows that depression was also relat- ed to having a mental health visit. PTSD severity was not statistically significant. In model 3, which added age and marital status variables, read- justment stressors were no longer sig- nificant but depression was. Discussion Key findings The findings of this study, showing relatively low rates of early treatment seeking among returning soldiers, are consistent with previous literature (15). We found that only 34% of Na- tional Guard veterans who scored positive for PTSD had made a post- deployment mental health visit and

- 16. that psychotropic medication had been prescribed to only 23%. The rates of medication usage in this study were slightly lower than those report- ed by Kehle and colleagues (16), in which 30% of OIF National Guard soldiers with PTSD received psy- chotropic treatment. The rate differ- ences between this study and those reported by Kehle and colleagues may be accounted for by the length of time in which utilization was as- sessed, which varied across the stud- ies (three months versus up to six months, respectively). The 11% of re- spondents in our sample who scored positive for PTSD was also compara- ble with that found in the Kehle and colleagues study. Results were mixed in terms of meeting the treatment needs of OIF soldiers with PTSD. It is estimated that 7% of the U.S. population with PTSD seeks care within the first year of onset, and our results show that more OIF National Guard soldiers were engaging with early mental health care compared with their civil- ian counterparts (17). This finding provides some support for recent policies, such as five-year access to Veterans Health Administration care among soldiers serving in Iraq or Afghanistan, increased education and awareness of combat-related stress,

- 17. and routine assessment of mental health conditions (18,19). However, the treatment utilization rate report- ed for National Guard soldiers with PTSD means that approximately two- thirds were without any early mental health treatment contact. Thus addi- tional policies and strategies for screening and referral should be con- PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES � ps.psychiatryonline.org � September 2012 Vol. 63 No. 9885588 TTaabbllee 33 Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom severity and readjustment stressors among 157 National Guard veterans with and without any postdeployment mental health visit Any mental health visit postdeployment No Yes All veterans Readjustment stressor N % N % N % Marital problemsa 28 30 31 59 59 40 Decision to divorce or separate 20 21 18 34 38 26 Problems with childrenb 15 16 18 34 33 22 Job status worsened 28 29 21 40 49 33 Lost job or businessb 14 15 16 31 30 20 Serious financial problemsb 29 31 27 50 56 38 Problems paying mortgage 12 13 13 25 25 17 Bank began foreclosureb 2 2 6 12 8 6 Family member or loved one became

- 18. ill or passed awayb 25 26 23 43 48 32 PCL score (M±SD)c 58.9±8.7 60.6±7.3 59.5±8.2 PHQ-9 depression score (M±SD)b,d 20.6±5.9 23.7±6.4 21.7±6.2 a p<.001 for comparison between soldiers with and without any mental health visit postdeployment b p<.05 for comparison between soldiers with and without any mental health visit postdeployment c PTSD severity was derived from the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Possible scores range from 17 to 85, with a score above 50 indicating PTSD. d Depression score derived from the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire. Possible scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating greater depression. FFiigguurree 11 Relationship between readjustment stressors and postdeployment mental health visits among 157 National Guard veterans 0 10 20 30 40 50

- 19. 60 P e rc e n ta g e o f sa m p le No visit ≥1 visit No stressors 1–2 stressors ≥3 stressors sidered for improving treatment par- ticipation rates. In terms of this study’s key objec- tive, we found that readjustment stressors played a significant role in

- 20. early treatment seeking. Six out of nine readjustment stressors were in- dividually associated with having any mental health visit in the univariate analyses (Table 3). This effect was cu- mulative, with higher numbers of stressors being associated with higher rates of service utilization. The associ- ation between readjustment stressors and mental health service use was in- dependent of the severity of PTSD or depression symptoms. As noted, this relationship diminished considerably on adjustment for age and marital sta- tus. Also, depression levels remained a significant predictor of service use, even after adjustment for age and marital status. The finding that de- pression was a significant variable as- sociated with help seeking is consis- tent with previous research (5,20). The loss of significance of readjust- ment stress after analyses adjusted for demographic characteristics is likely due to our sample characteristics and the relationship of readjustment stress with age and with marital sta- tus. Researchers have suggested that readjustment stressors may be more relevant for National Guard soldiers, who tend to be older and have more developed familial and occupational roles than members of the active mil- itary components (5).

- 21. The results of this study, along with previous research, provide some sup- port for this interpretation. First, our sample of National Guard soldiers ap- peared to be older compared with samples from active-duty compo- nents studied by Hoge and colleagues (15) and others (21). Second, in our somewhat older sample, individual readjustment stressors were reported at high levels, with each often report- ed by more than 20% of the partici- pants. For example, 20% had lost their job or business, which compares with an unemployment rate of 9.8% in New Jersey during the period when these data were collected (Sep- tember 2009) (22). A similar rate (28%) of job loss was found in a pre- vious study with reserve-duty soldiers with PTSD (23). Third, a previous study using the same data set found that readjustment stressors were more common among National Guard soldiers who were older and either married or previously married (24). Combined with our finding that readjustment stressors were no longer significant after analyses ad- justed for age and marital status, these observations lend support to the view that National Guard soldiers tend to be older and more susceptible to the type of readjustment stressors

- 22. assessed in this study. This is because they will likely have more involved family and occupational roles that can be affected by their symptoms. Limitations To interpret the loss of significance of readjustment stress after adjustment for demographic variables, one should consider the types of readjust- ment stressors captured by our scale. Its items tap stressors that pertain more to veterans who are or who have been married. Note, however, that the scale used in this study was based on qualitative interviews with New Jersey National Guardsmen and was designed to capture the readjustment stressors that were most salient to this sample. Nevertheless, it is important to interpret these findings in terms of the specific readjustment stressors that were assessed (marital problems and job problems). Unmarried sol- diers may experience stress in areas that were not captured in our survey of readjustment stressors, which mainly inquired about marital, child, and occupational difficulties. Future studies should examine a broader ar- ray of readjustment stressors to better sort out their relationship to help seeking among soldiers varying in age range and marital status. A recently published scale may improve our abil-

- 23. PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES � ps.psychiatryonline.org � September 2012 Vol. 63 No. 9 885599 TTaabbllee 44 Multivariate analysis of predictors of postdeployment mental health visits among 157 National Guard soldiers Model 1 Model 2a Model 3b Measure OR 95% CI OR 95% CI OR 95% CI Readjustment stress (reference: none)c 1.29∗ ∗ 1.10–1.50 1.24∗ 1.05–1.47 1.17 .98–1.41 Axis I disorder PTSD symptomsd — — 1.00 .95–1.01 1.00 .95–1.06 Depressive symptomse — — 1.10∗ 1.03–1.05 1.10∗ 1.02 –1.18 Age (reference: 17–25) 26–39 — — — — 2.05 .76–5.54 ≥40 — — — — 2.72 .94–7.93 Marital status (reference: married or living as married) Never married — — — — .59 .23–1.49 Divorced, separated, or widowed — — — — 1.50 .52–4.36 a Adjusted for effects of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) severity and depression b Adjusted for same variables as model 2, plus age and marital status c Participants answered yes or no to nine potential stressors. d PTSD severity was derived from the PTSD Checklist. e Depression severity was derived from the Patient Health

- 24. Questionnaire–9. ∗ p<.05 ∗ ∗ p<.01 ity to study this issue, given its broad- er range of stressors assessed (25). The significance of readjustment stressors in the rate of early treatment seeking has useful implications for services designed to treat PTSD among soldiers. PTSD service deliv- ery models may consider meaningful- ly integrating interventions that help with marital and family functioning, as well as case management support for addressing financial and occupa- tional stressors. Also, motivation for treatment can be built by linking the goals of treatment to better function- ing with family and occupation. Given that PTSD treatment may be charac- terized by considerable attrition, ad- dressing these issues may improve treatment retention rates by aligning services with key motivators for seek- ing treatment (20,26). Also, outreach and awareness efforts can utilize readjustment stressors as a point of engagement, which would increase the numbers of veterans who visit with a professional and would be more likely to be screened and re-

- 25. ferred to treatment. Future studies can build on this research by examin- ing the degree to which returning sol- diers cite readjustment stressors as their reason for seeking care. Future studies can also examine the role that family members play in encouraging care seeking. There are other limitations worth noting. First, although the use of a three-month postdeployment win- dow was advantageous for studying early treatment contact, it provided a very limited window for examining treatment continuity. Second, it is critical that engagement occur within a context of optimal treatment quali- ty. Given the importance of treatment quality, we caution that our data could not describe involvement with empirically supported psychothera- pies for PTSD or other care quality indicators, such as wait times (6,7,27). We also did not have the data to de- scribe the type of mental health visit utilized or the type of professional that was contacted (psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy background, psy- chologist, psychiatrist, or informal source of care). Third, the data lacked information on the soldiers’ perspec- tives regarding PTSD and its treat- ment. Such data are critical for un- derstanding participants’ own reasons

- 26. for seeking care. Thus future studies should clarify whether soldiers report readjustment stressors as reasons for seeking care. Fourth, it is likely that a portion of soldiers with PTSD symp- toms at postdeployment will recover on their own. Our cross-sectional de- sign did not allow for an estimate of early mental health care seeking that accounts for those who may have a natural recovery (28). Yet it is impor- tant to note that our PCL cutoff of ≥50 likely identified a cohort of vet- erans with more severe PTSD symp- toms that are less likely to naturally remit. Still, future research can build on the results of this study by incor- porating a longitudinal design that can describe the natural remission among those who do not seek early mental health care. Conclusions Readjustment stressors among re- turning National Guard soldiers were fairly common, with many soldiers re- porting multiple occupational, finan- cial, and family stressors. Readjust- ment stressors generally were associ- ated with having an early mental health visit, and these effects ap- peared to be accounted for by older age and marital status. Most return- ing soldiers with PTSD do not seek early treatment, but rates of having a mental health visit were more favor-

- 27. able in this population than in the general population. Acknowledgments and disclosures This work was supported by a grant from the New Jersey Department of Military and Veter- ans Affairs. The authors report no competing interests. References 1. Sayer N, Noorbaloochi S, Frazier P, et al: Reintegration problems and treatment in- terests among Iraq and Afghanistan com- bat veterans receiving VA medical care. Psychiatric Services 61:589–597, 2010 2. Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Rosen- heck RA: Combat trauma: trauma with highest risk of delayed onset and unre- solved posttraumatic stress disorder symp- toms, unemployment, and abuse among men. Journal of Nervous and Mental Dis- ease 189:99–108, 2001 3. Smith MW, Schnurr PP, Rosenheck RA: Employment outcomes and PTSD symp- tom severity. Mental Health Services Re- search 7:89–101, 2005 4. Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al: Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to

- 28. care. New England Journal of Medicine 351:13–22, 2004 5. Kehle SM, Polusny MA, Murdoch M, et al: Early mental health treatment-seeking among US National Guard soldiers de- ployed to Iraq. Journal of Traumatic Stress 23:33–40, 2010 6. Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, et al: Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: outcome at academic and community clinics. Jour- nal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 73:953–964, 2005 7. Resick PA, Galovski TE, Uhlmansiek MOB, et al: A randomized clinical trial to dismantle components of cognitive pro- cessing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in female victims of interpersonal violence. Journal of Consulting and Clini- cal Psychology 76:243–258, 2008 8. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset dis- tributions of DSM-IV disorders in the Na- tional Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:593– 602, 2005 9. Sayer NA, Friedemann-Sanchez G, Spoont M, et al: A qualitative study of de- terminants of PTSD treatment initiation in veterans. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Bi-

- 29. ological Processes 72:238–255, 2009 10. Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, et al: The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, Validi- ty, and Diagnostic Utility. Presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, Tex, Oct 1993 11. Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, et al: Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behaviour Re- search and Therapy 34:669–673, 1996 12. The Iowa Persian Gulf Study Group: Self- reported illness and health status among Gulf War soldiers: a population-based study. JAMA 277:238–245, 1997 13. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, et al: The utility of the SCL-90-R for the diag- nosis of war-zone related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 9:111–128, 1996 14. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL: The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity meas- ure. Psychiatric Annals 32:1–7, 2002 15. Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al: Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine 351:13–22, 2004 16. Kehle SM, Polusny MA, Murdoch M, et al:

- 30. Early mental health treatment-seeking among US National Guard soldiers de- ployed to Iraq. Journal of Traumatic Stress 23:33–40, 2010 17. Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al: PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES � ps.psychiatryonline.org � September 2012 Vol. 63 No. 9886600 Failure and delay of initial treatment con- tact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replica- tion. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:603–613, 2005 18. Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, et al: Getting beyond “Don’t Ask; Don’t Tell”: an evaluation of US Veterans Administration postdeployment mental health screening of veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. American Journal of Public Health 98:714–720, 2008 19. National Defense Authorization Act of 2008, no HR 4986 (110 Cong 2008) 20. Seal KH, Maguen S, Cohen B, et al: VA mental health services utilization in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in the first year of receiving new mental health diagnoses. Journal of Traumatic Stress 23:5–16, 2010 21. Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, et al: The

- 31. prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active com- ponent and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Archives of General Psychiatry 67:614– 623, 2010 22. Regional and State Employment and Un- employment: September 2009. Washing- ton, DC, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Oct 21, 2009. Available at www.bls.gov/news. release/archives/laus_10212009.pdf 23. Riviere LA, Kendall-Robbins A, McGurk D, et al: Coming home may hurt: risk fac- tors for mental ill health in US reservists after deployment in Iraq. British Journal of Psychiatry 198:136–142, 2011 24. Kline A, Ciccone DS, Black C, et al: Suici- dal ideation among National Guard troops deployed to Iraq: the association with post- deployment readjustment problems. Jour- nal of Nervous and Mental Disease 199: 914–920, 2011 25. Sayer NA, Frazier P, Orazem RJ, et al: Mil- itary to civilian questionnaire: a measure of postdeployment community reintegration difficulty among veterans using Depart- ment of Veterans Affairs medical care. Journal of Traumatic Stress 24:660–670, 2011 26. Spoont MR, Hodges J, Murdoch M, et al:

- 32. Race and ethnicity as factors in mental health service use among veterans with PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress 22: 648–653, 2009 27. Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, et al: Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clini- cal Psychology 74:898–907, 2006 28. Rothbaum BO, Foa EB, Riggs DS, et al: A prospective examination of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress 5:455–475, 1992 PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES � ps.psychiatryonline.org � September 2012 Vol. 63 No. 9 886611 SSuubbmmiissssiioonnss ffoorr DDaattaappooiinnttss CCoolluummnn IInnvviitteedd Submissions to the journal’s Datapoints column are invited. Datapoints encour- ages the rapid dissemination of relevant and timely findings related to clinical and policy issues in psychiatry. National data are preferred. Areas of interest in- clude diagnosis and practice patterns, treatment modalities, treatment sites, pa- tient characteristics, and payment sources. The analyses should be straightfor- ward, so that the figure or figures tell the story. The text should follow the stan- dard research format to include a brief introduction, description of the methods

- 33. and data set, description of the results, and comments on the implications or meanings of the findings. Datapoints columns, which have a one-page format, are typically 350 to 400 words of text with one or two figures. Because of space constraints, submissions with multiple authors are discouraged; submissions with more than four authors should include justification for additional authors. Inquiries or submissions should be directed to column editors Amy M. Kil- bourne, Ph.D., M.P.H. ([email protected]), or Tami L. Mark, Ph.D. (tami. [email protected]). Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Running head: EVALUATION OF A QUALITATIVE STUDY 1 EVALUATION OF A QUALITATIVE STUDY 9 Evaluation of a Qualitative Study First and Last Name Capella University Evaluation of a Qualitative Study

- 34. For this assignment you will locate an article from the peer- reviewed scholarly journals in your field using one of the databases available in the Capella University Library. This assignment should be between 4 and 6 pages in length, double- spaced using 12-point Times New Roman font, not counting the title page and reference section. You will notice the running head contains the words “evaluation of a quantitative study” and it is presented in all capitals. Also, notice that the words “running head” appear only on the first page and just the running head itself appears on subsequent pages. Next, notice that the title on the second page above is centered and capitalized but it is not in bold. This follows the example on page 42 of the APA Manual and also a second example found on page 54. Below you will notice that headings have been provided for this assignment. They follow the protocols for formatting level one and two headings found on page 62 and the example presented on page 58 of the APA Manual. It is sound practice to consult the APA Manual for formatting guidance. In the section immediately under the title, you are to provide a brief introduction to your assignment; however, you should not create a heading that states “Introduction.” You should present your introduction without a heading in order to comply with the guidance offered on page 63 of the APA Manual. Your introduction should tell the reader what the paper is about, such as what study is being evaluated and how your evaluation will proceed. A single brief paragraph is all that is required. You can find more information about how to develop an introduction at the Capella Writing Center. Evaluation of the Research Problem

- 35. In most cases the research problem appears early on in a research report. However, it is not always set off in its own section with a clear heading identifying it. You may have to do a bit of detective work to locate the description of the research problem. In your own words, without using direct quotes, summarize the research problem. Evaluating the Significance of the Problem Address the following questions. Does the problem statement indicate a counseling issue to study? You will have to make a judgment call as to whether or not the research article addresses a counseling issue and explain why or why not you have taken this position. Has the author provided evidence that this issue is important? Briefly describe the evidence presented in the discussion of the research problem that demonstrates this is an important issue deserving of being researched. Summarize in your own words, not direct quotes, the evidence presented and explain your own view of whether or not this is an important issue. Evaluation of the Literature Review Sometimes the literature review is nicely organized and set off in its own section with thoughtful headings. In other instances, comments on the literature associated with the research topic are scattered throughout the research report. Develop your evaluation of the literature review portion of the article. Points to think about in your evaluation are how well the author(s) tell the story of the topic by synthesizing the literature they have reviewed, and what themes are present in the literature review. Another point to consider is whether it

- 36. appears that the author(s) conducted an unbiased review of the literature, presenting more than one possible point of view. Evaluation of Research Purpose Statement and Questions Qualitative is a broad approach to research, consisting of many specific research designs. Examples are: grounded theory, case study, narrative, phenomenological, and ethnographic. Each research design has been developed to address certain kinds of research questions. Researchers should explicitly state the name of their chosen research design, but sometimes they do not. Likewise, sometimes authors state their purpose statement and research questions very clearly and sometimes they do not. Use your growing knowledge to find these elements in the article you are evaluating. Formal hypotheses are devices that are used for statistical analyses, so they will probably not appear in qualitative studies. Research Design Name the research design used and briefly, in your own words, describe how this design is going to address what the researchers want to know. For example, a phenomenological design will explore the lived subjective experience of a group of people who share an experience in common. Research Purpose Statement The research purpose statement declares the intent of the study. An example is: The purpose of the study is to use phenomenological research to explore the lived experience of intentionally childfree Hispanic women. Identify the research purpose statement, and offer your thoughtful opinion on how the author(s) presented their purpose. If you found the purpose statement lacking, be specific as to why.

- 37. Research Questions Research questions may be stated as questions or declarative statements. They have a specific focus. An example is: what is the lived experience of intentionally and permanently childfree Hispanic women? Sometimes the research questions are clearly identified in a research report, other times you have to look for them, and sometimes they are not presented at all. Examine your article and list the research questions if they are presented. Offer your opinion on how well the research question was developed. There may be more than one research question. Evaluation of Data Collection Plan In your own words, without using direct quotes, describe how participants were selected for this study. Identify the type of sampling strategy that was used in this research study. It will probably be explicitly stated in the article, using terms such as convenience, purposeful or snowball. Explain why you have taken this position (other than, it says so in the article). Offer your opinion of how the selection of participants could be improved in order to produce a stronger study. Go beyond simply saying the sample could be larger, which would not demonstrate your growing knowledge of the purpose of specific sampling strategies. Remember, the purpose of sampling is different for qualitative studies than it is for quantitative studies. In qualitative studies, the goal is not to be able to generalize findings from the sample to the population. Selection of Participants In your own words without using direct quotes, describe how participants were selected for this study. Offer your assessment of what type of sampling was used in this research report. Offer your opinion of how the selection of participants

- 38. could be improved in order to produce a stronger study. Gaining Permission Qualitative research is usually more intrusive than quantitative research because qualitative researchers typically spend more time at the research site and engage with the participants more directly than quantitative researchers. As a result, qualitative researchers have to be more sensitive and thoughtfully respect individual participants and research sites. Briefly summarize how the researchers gained permission to enter the research site and also how they obtained informed consent from the research participants to gather data. Offer an evaluation of whether or not the researchers gained permission according to ethical standards. If this is not described in the research report, offer a brief explanation of how you would have gained permission and consent if you were conducting the research project. Determining the Data to Collect In your own words, without using direct quotes, briefly describe the data that was collected in order to fulfill the study’s purpose and answer the research questions. The primary forms of data in qualitative research are observations, interviews and questionnaires, documents, and audiovisual materials. Which of these forms of data were collected? Were any other forms of data collected? Offer an evaluation of the appropriateness of the data that was collected in order for meeting the study’s goals. Recording Data Data recording protocols are usually forms designed by qualitative researchers to record information during interviews and observations. Did the researcher(s) describe the protocols they used? If so, what were they? Offer an evaluation of the effectiveness of these protocols. If they are not described, what

- 39. protocols would you recommend for this study? Evaluation of Data Analysis and Interpretation Plan In order to develop this section you may refer to the sections of the course text which address data analysis and interpretation for specific qualitative research designs. Most of the data collected by qualitative researchers involves transcripts of interviews and field notes. Some kind of coding of the data takes place. There are many specific procedures for coding and analyzing the data. Two specific strategies are thematic analysis and the constant comparative method. Preparing and Organizing Data for Analysis In your own words, briefly describe how the researcher(s) prepared and organized their data for analysis. Offer an evaluation of the effectiveness of this process. If this is not described in the research report, explain how you would have done it. Exploring and Coding the Data In your own words, briefly describe how the researcher(s) explored and coded the data. Offer an evaluation of the effectiveness of this process. If this is not described in the research report, explain how you would have done it. Using Codes to Build Description and Themes In your own words, briefly describe how the researcher(s) built description and themes. Offer an evaluation of the effectiveness of the process. If this is not described in the research report, explain how you would have done it.Representing and Reporting Findings

- 40. Typically qualitative findings are presented in tables, figures and narrative. In your own words, briefly describe how the researcher(s) reported their findings. Offer your opinion of how effectively you feel their findings were presented and offer suggestions for improvement. Interpreting Findings Qualitative researchers must step back and form larger meanings about the phenomenon under investigation based on their personal views, comparisons with past studies described in the literature, or both. Offer an evaluation of the meaningfulness of the interpretation provided in the research report. Briefly summarize the limitations of the study pointed out by its author(s). If no limitations are offered, present what you consider to be its limitations. Validating the Accuracy of the Findings Typically, qualitative researchers rely on three techniques to validate their findings: triangulation, member checking, and external auditing. Briefly summarize how the researchers validated their findings. Offer an evaluation of the effectiveness of the process. If they do not describe how this was done, explain how you would have validated the findings. Evaluation of Ethical and Culturally Relevant Strategies Qualitative research typically involves entering the research site for an extended period of time, and extensively interacting with participants. Interviews may involve collecting in-depth and highly personal information. In your opinion, how well did the researcher(s) address ethical issues? If the research report does not provide this information, what steps would you have taken if you were doing the research? Conclusion

- 41. Offer your overall assessment of the quality of the research report. Explain how you could use the information in the research report to inform your own work in the counseling profession. Complete the reference section below using proper APA formatting. References Use this area to list the resources you cited in your paper. The reference below provides an example citation for an article. For more information about References, see chapter 7 in the APA 6th Edition Manual. Delete this text before submitting your assignment. Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Title of article. Title of Periodical, volume#(issue#), xx–xx.