This randomized clinical trial compared the effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and usual care for treating chronic low back pain. 342 adults with chronic low back pain were randomly assigned to receive MBSR, CBT, or usual care. At 26 weeks, participants receiving MBSR or CBT reported significantly greater improvement in back pain and functional limitations compared to usual care. There were no significant differences in outcomes between MBSR and CBT. These findings suggest that MBSR may be an effective treatment option for chronic low back pain.

![Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or Usual Care on Back Pain

andFunctionalLimitationsinAdultsWithChronicLowBackPain

A Randomized Clinical Trial

Daniel C. Cherkin, PhD; Karen J. Sherman, PhD; Benjamin H. Balderson, PhD; Andrea J. Cook, PhD;

Melissa L. Anderson, MS; Rene J. Hawkes, BS; Kelly E. Hansen, BS; Judith A. Turner, PhD

IMPORTANCE Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) has not been rigorously evaluated

for young and middle-aged adults with chronic low back pain.

OBJECTIVE To evaluate the effectiveness for chronic low back pain of MBSR vs cognitive

behavioral therapy (CBT) or usual care.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS Randomized, interviewer-blind, clinical trial in an

integrated health care system in Washington State of 342 adults aged 20 to 70 years with

chronic low back pain enrolled between September 2012 and April 2014 and randomly

assigned to receive MBSR (n = 116), CBT (n = 113), or usual care (n = 113).

INTERVENTIONS CBT (training to change pain-related thoughts and behaviors) and MBSR

(training in mindfulness meditation and yoga) were delivered in 8 weekly 2-hour groups.

Usual care included whatever care participants received.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Coprimary outcomes were the percentages of participants

with clinically meaningful (Ն30%) improvement from baseline in functional limitations

(modified Roland Disability Questionnaire [RDQ]; range, 0-23) and in self-reported back pain

bothersomeness (scale, 0-10) at 26 weeks. Outcomes were also assessed at 4, 8, and 52 weeks.

RESULTS There were 342 randomized participants, the mean (SD) [range] age was 49.3 (12.3)

[20-70] years, 224 (65.7%) were women, mean duration of back pain was 7.3 years

(range, 3 months-50 years), 123 (53.7%) attended 6 or more of the 8 sessions, 294 (86.0%)

completed the study at 26 weeks, and 290 (84.8%) completed the study at 52 weeks. In

intent-to-treat analyses at 26 weeks, the percentage of participants with clinically meaningful

improvement on the RDQ was higher for those who received MBSR (60.5%) and CBT

(57.7%) than for usual care (44.1%) (overall P = .04; relative risk [RR] for MBSR vs usual care,

1.37 [95% CI, 1.06-1.77]; RR for MBSR vs CBT, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.77-1.18]; and RR for CBT vs usual

care, 1.31 [95% CI, 1.01-1.69]). The percentage of participants with clinically meaningful

improvement in pain bothersomeness at 26 weeks was 43.6% in the MBSR group and 44.9%

in the CBT group, vs 26.6% in the usual care group (overall P = .01; RR for MBSR vs usual care,

1.64 [95% CI, 1.15-2.34]; RR for MBSR vs CBT, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.78-1.36]; and RR for CBT vs

usual care, 1.69 [95% CI, 1.18-2.41]). Findings for MBSR persisted with little change at 52

weeks for both primary outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE Among adults with chronic low back pain, treatment with

MBSR or CBT, compared with usual care, resulted in greater improvement in back pain and

functional limitations at 26 weeks, with no significant differences in outcomes between

MBSR and CBT. These findings suggest that MBSR may be an effective treatment option for

patients with chronic low back pain.

TRIAL REGISTRATION clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01467843

JAMA. 2016;315(12):1240-1249. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2323

Editorial page 1236

Author Video Interview and

JAMA Report Video at

jama.com

Supplemental content at

jama.com

CME Quiz at

jamanetworkcme.com

Author Affiliations: Group Health

Research Institute, Seattle,

Washington (Cherkin, Sherman,

Balderson, Cook, Anderson, Hawkes,

Hansen); Department of Health

Services, University of Washington,

Seattle (Cherkin); Department of

Family Medicine, University of

Washington, Seattle (Cherkin);

Department of Epidemiology,

University of Washington, Seattle

(Sherman); Department of

Biostatistics, University of

Washington, Seattle (Cook);

Department of Psychiatry and

Behavioral Sciences, University of

Washington, Seattle (Turner);

Department of Rehabilitation

Medicine, University of Washington,

Seattle (Turner).

Corresponding Author: Daniel C.

Cherkin, PhD, Group Health

Research Institute, 1730 Minor Ave,

Ste 1600, Seattle, WA 98101

(cherkin.d@ghc.org).

Research

Original Investigation

1240 (Reprinted) jama.com

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/07/2016](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbsrvscbt-160507153023/75/MBSR-vs-CBT-1-2048.jpg)

![Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

adherence to the protocol, either in person or via audio re-

cording, for at least 1 session per group.

MBSR was modeled closely after the original MBSR

program9

—adaptated from the 2009 MBSR instructor’s

manual18

byaseniorMBSRinstructor.TheMBSRprogramdoes

not focus specifically on a particular condition such as pain.

All classes included didactic content and mindfulness prac-

tice (body scan, yoga, meditation [attention to thoughts, emo-

tions, and sensations in the present moment without trying

to change them, sitting meditation with awareness of breath-

ing, and walking meditation]).

The CBT protocol included CBT techniques most com-

monly applied and studied for chronic low back pain.8,19-22

The intervention included (1) education about chronic pain,

relationships between thoughts and emotional and physical

reactions, sleep hygiene, relapse prevention, and mainte-

nance of gains; and (2) instruction and practice in changing

dysfunctional thoughts, setting and working toward behav-

ioral goals, relaxation skills (abdominal breathing, progres-

sive muscle relaxation, and guided imagery), activity pacing,

and pain-coping strategies. Between-session activities

included reading chapters of The Pain Survival Guide: How to

Reclaim Your Life.21

Mindfulness, meditation, and yoga tech-

niques were proscribed in CBT; methods to challenge dys-

functional thoughts were proscribed in MBSR.

Follow-up

Trained interviewers, masked to treatment group, collected

data by telephone at baseline (before randomization) and af-

ter randomization at weeks 4 (midtreatment), 8 (posttreat-

ment), 26 (primary end point), and 52. Participants were com-

pensated $20 for each interview.

Measures

Sociodemographic and back pain information was obtained at

baseline (Table 1). All primary outcome measures were admin-

istered at each time point; secondary outcomes were as-

sessed at all time points except 4 weeks.

Coprimary Outcomes

Back pain–related functional limitation was assessed by the

RDQ16

and modified to 23 (vs the original 24) items and to

ask about the past week rather than today only. Higher

scores (range 0-23) indicate greater functional limitation.

The original RDQ has demonstrated reliability, validity, and

sensitivity to clinical change.23

Back pain bothersomeness in

the past week was measured on a 0 to 10 scale (0 indicates

not at all bothersome; 10 indicates extremely bothersome).

Primary analyses of this study examined the percentages of

participants with clinically meaningful improvement (≥30%

improvement from baseline)24

on each measure. Secondary

Figure. Flow of Participants Through Trial Comparing Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction With Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Usual Care

for Chronic Low Back Pain

1425 Excluded

412 Pain <3 months

338 Unable to attend classes

357 Other

122 Pain rated <4 on 0-10 scale

196 Activity interference <3 on 0-10 scale

1767 Individuals assessed for eligibility

342 Randomized

113 Randomized to receive usual care 116 Randomized to receive mindfulness-

based stress reductiona

13 Did not attend any classes

3 Time conflict or logisticsc

2 Illness or injury

8 Unknown

113 Randomized to receive cognitive

behavioral therapyb

13 Did not attend any classes

4 Time conflict or logisticsc

4 Illness or injury

5 Unknown

113 Included in analysis of coprimary

and secondary outcomes

116 Included in analysis of coprimary

and secondary outcomes

112 Included in analysis of coprimary

and secondary outcomes

1 Excluded (missing baseline data)

100 Followed up at 4 wk

94 Followed up at 8 wk

95 Followed up at 26 wk

92 Followed up at 52 wk

97 Followed up at 4 wk

98 Followed up at 8 wk

92 Followed up at 26 wk

92 Followed up at 52 wk

108 Followed up at 4 wk

106 Followed up at 8 wk

107 Followed up at 26 wk

106 Followed up at 52 wk

a

Of the 116 participants randomized to receive mindfulness-based stress

reduction, 103 attended at least 1 class and 59 attended at least 6 classes. For

those who attended at least 1 class, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) was

6 (3-7) classes per participant. Participants were recruited in 10 separate

waves (median 12.5 [IQR, 7-16] participants per wave).

b

Of the 113 participants randomized to receive cognitive behavioral therapy,

100 attended at least 1 class and 64 attended at least 6 classes. For those who

attended at least 1 class, the median (IQR) was 6 (3-7) classes per participant.

Participants were recruited in 10 separate waves (median 13 [IQR, 5-14]

participants per wave).

c

Logistics, given as a reason for not attending any classes, specifically refers to

transportation problems (no car or acceptable bus schedules) or obtaining

child care during classes.

Research Original Investigation Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

1242 JAMA March 22/29, 2016 Volume 315, Number 12 (Reprinted) jama.com

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/07/2016](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbsrvscbt-160507153023/75/MBSR-vs-CBT-3-2048.jpg)

![Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

analyses compared the adjusted mean change from baseline

between groups.

Secondary Outcomes

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health

Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8; range, 0-24; higher scores indicate

greater severity).25

Anxiety was measured using the 2-item

Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-2; range, 0-6; higher

scores indicate greater severity).26

Characteristic pain inten-

sity was assessed as the mean of 3 ratings (gauged on a 0-10

scale; current, worst, and average back pain in the previous

month; range; higher scores indicate greater intensity) from

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Treatment Group

No. (%)

All

(n = 341)

Usual Care

(n = 113)

Mindfulness-Based

Stress Reduction

(n = 116)

Cognitive Behavioral

Therapy

(n = 112)

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Age, mean (SD), y 49.3 (12.3) 48.9 (12.5) 50.0 (11.9) 49.1 (12.6)

Women 224 (65.7) 87 (77.0) 71 (61.2) 66 (58.9)

Education

≤High school 26 (7.6) 5 (4.4) 14 (12.1) 7 (6.3)

Some college or vocational

school

114 (33.4) 37 (32.7) 41 (35.3) 36 (32.1)

College graduate 201 (58.9) 71 (62.8) 61 (52.6) 69 (61.6)

Race

White 278 (82.5) 88 (80.0) 97 (84.4) 93 (83.0)

Asian 13 (3.9) 3 (2.7) 4 (3.5) 6 (5.4)

African American 11 (3.3) 3 (2.7) 4 (3.5) 4 (3.6)

Othera

35 (10.4) 16 (14.6) 10 (8.7) 9 (8.0)

Hispanic ethnicity 23 (6.8) 8 (7.1) 5 (4.3) 10 (8.9)

Married or living as married 249 (73.0) 79 (69.9) 85 (73.3) 85 (75.9)

Annual family income

> US $55 000

206 (62.6) 72 (66.1) 66 (58.4) 68 (63.6)

Employed 263 (77.1) 89 (78.8) 87 (75.0) 87 (77.7)

Back Pain History and Expectations

≥1 Year since 1 week without LBP 269 (78.9) 86 (76.1) 93 (80.2) 90 (80.4)

Had spinal injection for LBP 8 (2.7) 3 (3.1) 3 (3.0) 2 (2.0)

Currently reporting “a lot of pain”

in site other than back

100 (29.3) 35 (31.0) 34 (29.3) 31 (27.7)

Back pain in last 180 days,

median (IQR), d

160 (100-180) 160 (100-180) 170 (115-180) 160 (100-180)

Expects LBP to “be much better

or gone” in 1 year

101 (29.8) 36 (31.9) 34 (29.6) 31 (27.9)

Expects LBP self-management

program will be helpful,

mean (SD), scoreb

7.5 (1.9) 7.8 (1.8) 7.6 (2.0) 7.2 (1.8)

Baseline Measures of Primary Outcome Scores

RDQ (modified), mean (SD)c

11.4 (4.8) 10.9 (4.8) 11.8 (4.7) 11.5 (5.0)

Pain bothersomeness rating,

mean (SD)d

6.0 (1.6) 6.0 (1.6) 6.1 (1.6) 6.0 (1.5)

Baseline Measures of Secondary Outcome Scores

Characteristic pain intensity,

mean (SD)d

5.9 (1.3) 5.8 (1.3) 6.0 (1.3) 5.8 (1.2)

PHQ-8, mean (SD)e

5.6 (4.1) 5.3 (3.8) 5.7 (4.0) 5.7 (4.4)

GAD-2, mean (SD)f

1.4 (1.5) 1.5 (1.3) 1.4 (1.5) 1.4 (1.5)

GAD-2, median (IQR)f

1 (0-2) 1 (0-2) 1 (0-2) 1 (0-2)

SF-12 Physical, mean (SD)g

39.1 (7.9) 39.7 (7.6) 38.2 (7.5) 39.4 (8.6)

SF-12 Mental, mean (SD)g

39.9 (7.9) 39.8 (7.4) 40.6 (8.1) 39.4 (8.2)

Baseline Measures of Other Secondary Outcomes

Any medication use for LBP

in past week

252 (73.9) 82 (72.6) 85 (73.3) 85 (75.9)

Opioids use for LBP in past week 38 (11.1) 12 (10.6) 14 (12.1) 12 (10.7)

Back-specific exercise ≥3 days

in past week

137 (40.2) 44 (38.9) 48 (41.4) 45 (40.2)

General exercise ≥3 days

in past week

167 (49.0) 53 (46.9) 57 (49.1) 57 (50.9)

Abbreviations: GAD-2, Generalized

Anxiety Disorder-2; IQR, interquartile

range; LBP, low back pain;

PHQ-8, Patient Health

Questionnaire-8; RDQ, Roland

Disability Questionnaire;

SF-12, 12-Item Short Form

Health Survey.

a

Race/ethnicity subcategory of Other

indicates multiracial (19), other (not

specified [9]), missing (5), Native

American/Pacific Islander (2).

b

LBP self-management score range is

0 to 10. Higher scores indicate more

program success.

c

Modified RDQ score range is 0 to

23. Higher scores indicate worse

function.

d

Pain bothersomeness rating and

characteristic pain intensity score

ranges are both 0 to 10. Higher

scores indicate greater pain.

e

PHQ-8 score range is 0 to 24.

Higher scores indicate more

depression.

f

GAD-2 score range is 0 to 6. Higher

scores indicate more anxiety.

g

SF-12 physical and mental

component scores range from 0 to

100. Lower scores indicate poorer

health status and higher ones

indicate higher function.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Original Investigation Research

jama.com (Reprinted) JAMA March 22/29, 2016 Volume 315, Number 12 1243

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/07/2016](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbsrvscbt-160507153023/75/MBSR-vs-CBT-4-2048.jpg)

![Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

domized to receive MBSR attended the 6-hour retreat. Over-

all follow-up response rates ranged from 89.2% (305 partici-

pants) at 4 weeks to 84.8%(290 participants) at 52 weeks and

were higher in the usual care group (95.6% [108] at 4 weeks

and 93.8% [106] at 52 weeks).

At baseline, treatment groups were similar in sociodemo-

graphic and pain characteristics except for more women in

usual care and fewer college graduates in the MBSR group

(Table 1). Overall, 269 (78.9%) reported at least 1 year since a

week without back pain and most reported pain on at least 160

of the previous 180 days. Mean duration of back pain was 7.3

years (range, 3 months-50 years). The mean (SD) RDQ score

(11.4 [4.8]) and pain bothersomeness rating (6.0 [1.6]) indi-

cated moderate levels of severity. Opioids use for pain during

Table 2. Coprimary Outcomes: Percentage of Participants With Clinically Meaningful Improvement by Treatment Group and Relative Risks Comparing

Treatment Groups (Adjusted Imputed Analyses)a,b

Follow-up

Week

% (95% CI) With Clinically Meaningful Improvement

P Value

for Omnibusc

Relative Risk (95% CI)

Usual Care

Mindfulness-Based

Stress Reduction

Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy

Mindfulness-Based

Stress Reduction vs

Usual Care

Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy vs

Mindfulness-Based

Stress Reduction

Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy vs

Usual Care

Roland Disability Questionnaire Results

4 27.3 (20.3-36.6) 34.5 (26.8-44.3) 24.7 (18.1-33.8) .23 1.26 (0.86-1.86) 0.72 (0.48-1.07) 0.91 (0.59-1.39)

8 35.4 (27.6-45.2) 47.4 (38.9-57.6) 51.9 (43.6-61.7) .04d

1.34 (0.98-1.84) 1.10 (0.84-1.42) 1.47 (1.09-1.98)d

26 44.1 (35.9-54.2) 60.5 (52.0-70.3) 57.7 (49.2-67.6) .04d

1.37 (1.06-1.77)d

0.95 (0.77-1.18) 1.31 (1.01-1.69)d

52 48.6 (40.3-58.6) 68.6 (60.3-78.1) 58.8 (50.6-68.4) .01d

1.41 (1.13-1.77)d

0.86 (0.70-1.04) 1.21 (0.95-1.54)

Pain Bothersomeness Results

4 20.6 (14.6-28.9) 19.1 (13.3-27.4) 21.7 (15.3-30.6) .88 0.93 (0.56-1.52) 1.14 (0.69-1.87) 1.05 (0.65-1.71)

8 24.7 (18.1-33.6) 36.1 (28.3-46.0) 33.8 (26.5-43.2) .15 1.46 (0.99-2.16) 0.94 (0.67-1.32) 1.37 (0.93-2.02)

26 26.6 (19.8-35.9) 43.6 (35.6-53.3) 44.9 (36.7-55.1) .01d

1.64 (1.15-2.34)d

1.03 (0.78-1.36) 1.69 (1.18-2.41)d

52 31.0 (23.8-40.3) 48.5 (40.3-58.3) 39.6 (31.7-49.5) .02d

1.56 (1.14-2.14)d

0.82 (0.62-1.08) 1.28 (0.91-1.79)

a

Estimates from generalized estimating equations 2-step imputed model

adjusting for baseline outcome score, sex, age, education, and pain duration

(<1 y vs Ն1 y since experiencing a week without back pain).

b

n = 341 Included in the analysis; 1 randomized participant who did not

complete the baseline survey was excluded. Follow-up rates (sample sizes

before imputation) at each time point by randomization group are detailed in

the Figure. In addition, 1 participant in the mindfulness-based stress reduction

group at 8 weeks and 1 in the usual care group at 26 weeks were missing data

for the pain bothersomeness outcome. Sample sizes before imputation for

each outcome at each time point are provided by randomization group

(eTable in Supplement 2).

c

Wald P value.

d

P value is less than .05 for pairwise comparisons.

Table 3. Coprimary Outcomes: Mean (95% CI) Change by Treatment Group and Mean (95% CI) Differences Between Treatment Groups

(Adjusted Imputed Analyses)a,b

Follow-up

Week

Change From Baseline, Mean (95% CI)

P Value for

Omnibusc

Between-Group Differences, Mean (95% CI)

Usual Care

Mindfulness-Based

Stress Reduction

Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy

Mindfulness-Based

Stress Reduction vs

Usual Care

Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy vs

Mindfulness-Based

Stress Reduction

Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy vs

Usual Care

Roland Disability Questionnaire Results

4 −1.28

(−1.91 to −0.65)

−1.93

(−2.61 to −1.25)

−1.44

(−2.10 to −0.78)

.37 −0.65

(−1.59 to 0.28)

0.49

(−0.46 to 1.45)

−0.16

(−1.07 to 0.76)

8 −1.83

(−2.59 to −1.07)

−3.40

(−4.22 to −2.59)

−3.37

(−4.14 to −2.60)

.005d

−1.57

(−2.70 to −0.45)d

0.04

(−1.11 to 1.18)

−1.54

(−2.61 to −0.46)d

26 −2.96

(−3.79 to −2.14)

−4.33

(−5.16 to −3.51)

−4.38

(−5.3 to −3.47)

.03d

−1.37

(−2.55 to −0.19)d

−0.05

(−1.31 to 1.21)

−1.42

(−2.66 to −0.18)d

52 −3.43

(−4.33 to −2.52)

−5.3

(−6.16 to −4.43)

−4.78

(−5.67 to −3.89)

.01d

−1.87

(−3.14 to −0.60)d

0.51

(−0.75 to 1.78)

−1.36

(−2.63 to −0.08)d

Pain Bothersomeness Results

4 −0.68

(−0.98 to −0.38)

−0.57

(−0.87 to −0.27)

−0.79

(−1.13 to −0.44)

.66 0.11

(−0.32 to 0.53)

−0.21

(−0.67 to 0.25)

−0.11

(−0.56 to 0.35)

8 −0.67

(−1.02 to −0.33)

−1.40

(−1.71 to −1.10)

−1.28

(−1.62 to −0.94)

.005d

−0.73

(−1.19 to −0.27)d

0.12

(−0.34 to 0.58)

−0.61

(−1.09 to −0.12)d

26 −0.84

(−1.21 to −0.46)

−1.48

(−1.86 to −1.11)

−1.56

(−2.02 to −1.11)

.02d

−0.64

(−1.18 to −0.11)d

−0.08

(−0.68 to 0.51)

−0.73

(−1.32 to −0.13)d

52 −1.10

(−1.48 to −0.71)

−1.95

(−2.32 to −1.59)

−1.76

(−2.14 to −1.39)

.005d

−0.85

(−1.39 to −0.32)d

0.19

(−0.33 to 0.71)

−0.67

(−1.20 to −0.13)d

a

Estimates are from generalized estimating equations 2-step imputed

model adjusting for baseline outcome score, sex, age, education,

and pain duration (<1 y vs Ն1 y since experiencing a week without

back pain).

b

There were 341 participants included in the analysis. Sample sizes before

imputation for each outcome at each time point are provided by

randomization group (eTable in Supplement 2).

c

Wald P value.

d

P value is less than .05 for pairwise comparisons.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Original Investigation Research

jama.com (Reprinted) JAMA March 22/29, 2016 Volume 315, Number 12 1245

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/07/2016](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbsrvscbt-160507153023/75/MBSR-vs-CBT-6-2048.jpg)

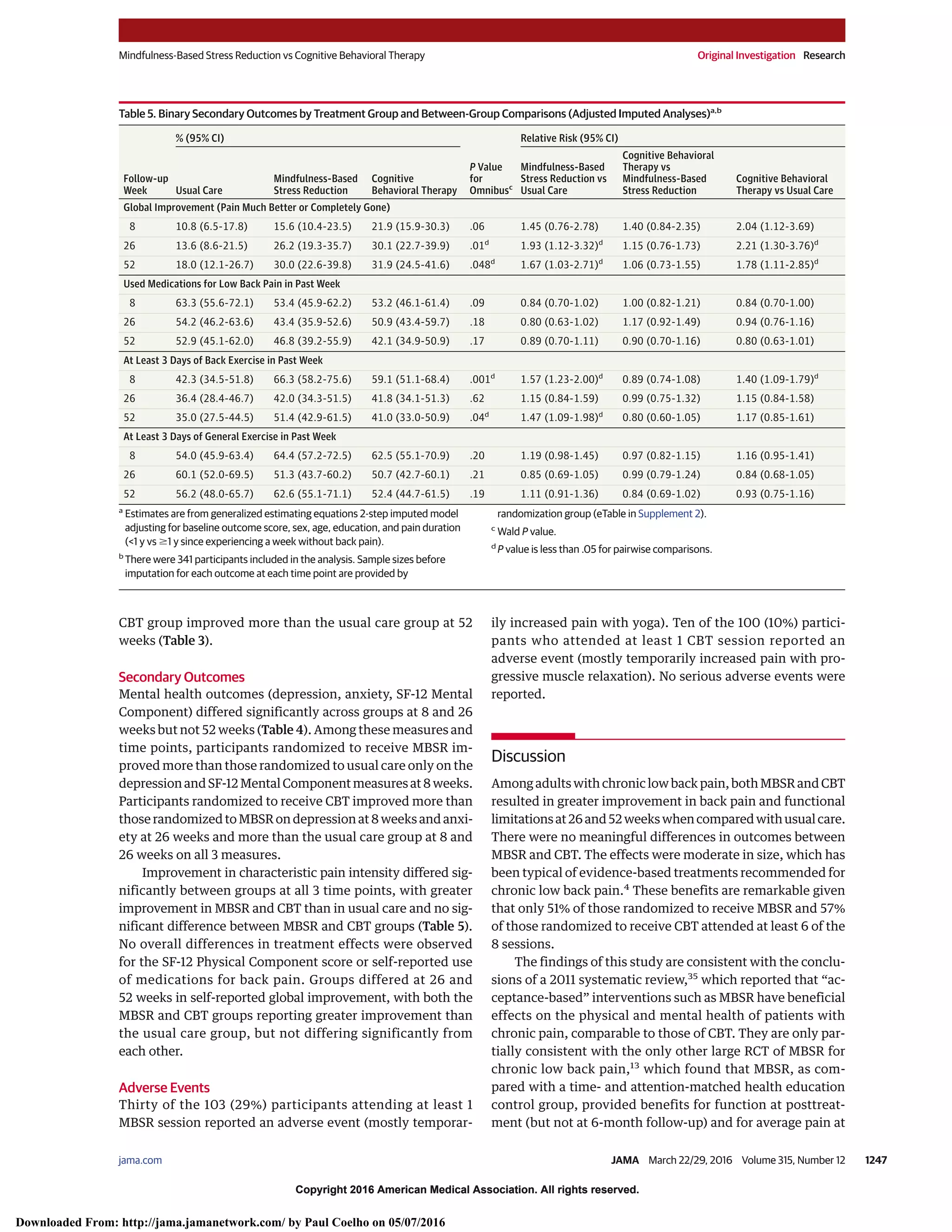

![Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

the past week was reported by 38 participants (11.1%). Seven-

teen percent had at least moderate levels of depression (PHQ-8

scores ≥10) and 18% had at least moderate levels of anxiety

(GAD-2 scores ≥3).

Coprimary Outcomes

At the 26-week primary end point, the groups differed signifi-

cantly (P = .04) in percent with clinically meaningful improve-

ment on the RDQ (MBSR 60.5%, usual care 44.1%, CBT 57.7%;

Table 2). Participants randomized to receive MBSR were more

likely than those randomized to usual care to show meaning-

ful improvement on the RDQ (RR, 1.37 [95% CI, 1.06-1.77]) but

did not differ significantly from those randomized to CBT. The

overall difference among groups in clinically meaningful im-

provement in pain bothersomeness at 26 weeks was also sta-

tistically significant (MBSR 43.6%, usual care 26.6%, CBT

44.9%;P = .01).ParticipantsrandomizedtoreceiveMBSRwere

more likely to show meaningful improvement when com-

pared with usual care (RR, 1.64 [95% CI, 1.15-2.34]) but not

when compared with CBT (RR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.78-1.36]). The

significant differences between MBSR and usual care and

the nonsignificant differences between MBSR and CBT, in

percent with meaningful function and pain improvement,

persisted at 52 weeks, with RRs similar to those at 26 weeks

(Table 2). CBT was superior to usual care for both primary out-

comesat26weeksbutnot52weeks.TreatmenteffectsofMBSR

and CBT were not apparent before end of treatment (8 weeks).

Generally similar results were found when the primary out-

comes were analyzed as continuous variables, although more

differences were statistically significant at 8 weeks, and the

Table 4. Mean Change From Baseline of Continuous Secondary Outcomes by Treatment Group and Between-Group Comparisons

(Adjusted Imputed Analyses)a,b

Follow-up

Week

Change Estimates, Mean (95% CI)

P Value for

Omnibusc

Between-Group Differences, Mean (95% CI)

Usual Care

Mindfulness-Based

Stress Reduction

Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy

Mindfulness-Based

Stress Reduction vs

Usual Care

Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy vs

Mindfulness-Based

Stress Reduction

Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy vs

Usual Care

Depression (PHQ-8)

8 −0.12

(−0.74 to 0.50)

−1.60

(−2.15 to −1.05)

−2.29

(−2.66 to −1.92)

<.001d

−1.48

(−2.31 to −0.64)d

−0.69

(−1.35 to −0.02)d

−2.17

(−2.89 to −1.45)d

26 −0.64

(−1.23 to −0.06)

−1.32

(−1.81 to −0.83)

−1.80

(−2.35 to −1.26)

.02d

−0.68

(−1.45 to 0.09)

−0.48

(−1.21 to 0.26)

−1.16

(−1.95 to −0.37)d

52 −0.88

(−1.50 to −0.27)

−1.51

(−2.09 to −0.92)

−1.72

(−2.28 to −1.16)

.13 −0.62

(−1.48 to 0.23)

−0.21

(−1.03 to 0.61)

−0.83

(−1.67 to 0.00)

Anxiety (GAD-2)

8 −0.09

(−0.32 to 0.13)

−0.33

(−0.56 to −0.10)

−0.51

(−0.69 to −0.33)

.02d

−0.24

(−0.56 to 0.09)

−0.18

(−0.47 to 0.11)

−0.41

(−0.70 to −0.13)d

26 0.02

(−0.24 to 0.28)

0.00

(−0.28 to 0.28)

−0.49

(−0.72 to −0.25)

.005d

−0.02

(−0.41 to 0.37)

−0.49

(−0.85 to −0.12)d

−0.51

(−0.86 to −0.16)d

52 −0.14

(−0.40 to 0.12)

−0.15

(−0.40 to 0.10)

−0.39

(−0.59 to −0.18)

.23 0.00

(−0.37 to 0.36)

−0.24

(−0.56 to 0.08)

−0.24

(−0.58 to 0.09)

Characteristic Pain Intensity

8 −0.37

(−0.62 to −0.12)

−1.00

(−1.28 to −0.73)

−0.86

(−1.12 to −0.59)

.002d

−0.63

(−1.01 to −0.26)d

0.15

(−0.24 to 0.53)

−0.49

(−0.84 to −0.13)d

26 −0.65

(−0.95 to −0.35)

−1.10

(−1.42 to −0.77)

−1.15

(−1.44 to −0.86)

.04d

−0.45

(−0.89 to −0.01)d

−0.05

(−0.50 to 0.39)

−0.50

(−0.92 to −0.09)d

52 −0.79

(−1.10 to −0.48)

−1.42

(−1.72 to −1.12)

−1.40

(−1.74 to −1.05)

.007d

−0.63

(−1.06 to −0.19)d

0.02

(−0.44 to 0.48)

−0.61

(−1.07 to −0.14)d

SF-12 Physical Component Score

8 2.21

(1.12 to 3.30)

3.69

(2.61 to 4.77)

3.24

(2.21 to 4.27)

.16 1.48

(−0.06 to 3.02)

−0.45

(−1.95 to 1.05)

1.03

(−0.48 to 2.54)

26 3.27

(2.09 to 4.44)

3.58

(2.15 to 5.01)

3.78

(2.56 to 5.00)

.84 0.31

(−1.53 to 2.16)

0.20

(−1.69 to 2.10)

0.52

(−1.19 to 2.22)

52 2.93

(1.70 to 4.16)

3.87

(2.55 to 5.19)

3.79

(2.55 to 5.03)

.50 0.94

(−0.86 to 2.74)

−0.08

(−1.91 to 1.75)

0.86

(−0.87 to 2.60)

SF-12 Mental Component Score

8 −0.65

(−1.86 to 0.55)

1.68

(0.57 to 2.79)

1.77

(0.82 to 2.72)

.004d

2.33

(0.68 to 3.99)d

0.09

(−1.37 to 1.54)

2.42

(0.87 to 3.97)d

26 −1.11

(−2.39 to 0.17)

0.45

(−0.85 to 1.76)

2.13

(0.86 to 3.40)

.002d

1.57

(−0.27 to 3.40)

1.68

(−0.12 to 3.47)

3.24

(1.44 to 5.04)d

52 0.75

(−0.58 to 2.08)

2.01

(0.74 to 3.28)

1.81

(0.59 to 3.03)

.36 1.26

(−0.60 to 3.11)

−0.19

(−1.95 to 1.56)

1.06

(−0.75 to 2.88)

Abbreviations: GAD-2, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2; PHQ-8, Patient Health

Questionnaire-8; SF-12, 12-Item Short Form Health Survey.

a

Estimates are from generalized estimating equations 2-step imputed model

adjusting for baseline outcome score, sex, age, education, and pain duration

(<1 y vs Ն1 y since experiencing a week without back pain).

b

There were 341 participants included in the analysis. Sample sizes before

imputation for each outcome at each time point are provided by

randomization group (eTable in Supplement 2).

c

Wald P value.

d

P value is less than .05 for pairwise comparisons.

Research Original Investigation Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

1246 JAMA March 22/29, 2016 Volume 315, Number 12 (Reprinted) jama.com

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/07/2016](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbsrvscbt-160507153023/75/MBSR-vs-CBT-7-2048.jpg)