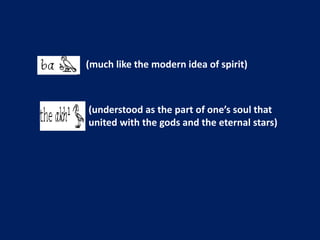

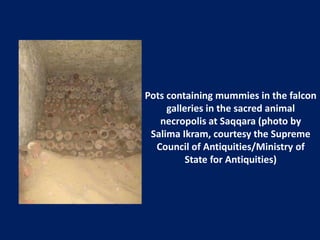

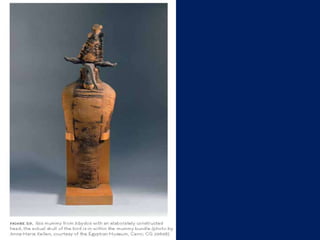

Birds played a significant role in ancient Egyptian religion. Various bird species represented different gods and aspects of the soul. The importance of birds in cult practice increased in the Late Period, as evidenced by installations of avian deities and millions of mummified birds offered as votives and buried in vast catacombs. These bird mummies provide a wealth of information on Egyptian culture, such as mummification practices, temple economics, veterinary medicine, and species present over time. Modern scientific analysis of the mummies continues to enhance understanding of ancient Egypt.