175684725 2nd-sales-cases

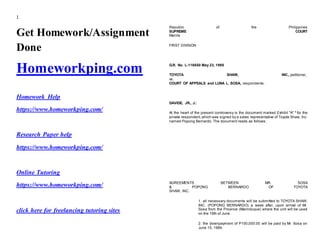

- 1. 1 Get Homework/Assignment Done Homeworkping.com Homework Help https://www.homeworkping.com/ Research Paper help https://www.homeworkping.com/ Online Tutoring https://www.homeworkping.com/ click here for freelancing tutoring sites Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila FIRST DIVISION G.R. No. L-116650 May 23, 1995 TOYOTA SHAW, INC., petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and LUNA L. SOSA, respondents. DAVIDE, JR., J.: At the heart of the present controversy is the document marked Exhibit "A" 1 for the private respondent,which was signed by a sales representative of Toyota Shaw, Inc. named Popong Bernardo. The document reads as follows: AGREEMENTS BETWEEN MR. SOSA & POPONG BERNARDO OF TOYOTA SHAW, INC. 1. all necessary documents will be submitted to TOYOTA SHAW, INC. (POPONG BERNARDO) a week after, upon arrival of Mr. Sosa from the Province (Marinduque) where the unit will be used on the 19th of June. 2. the downpayment of P100,000.00 will be paid by Mr. Sosa on June 15, 1989.

- 2. 2 3. the TOYOTA SHAW, INC. LITE ACE yellow, will be pick-up [sic] and released by TOYOTA SHAW, INC. on the 17th of June at 10 a.m.. Was this document, executed and signed by the petitioner's sales representative, a perfected contract of sale, binding upon the petitioner, breach of which would entitle the private respondentto damages and attorney's fees? The trial court and the Court of Appeals took the affirmative view. The petitioner disagrees. Hence, this petition for review oncertiorari. The antecedents as disclosed in the decisions of both the trial court and the Court of Appeals, as well as in the pleadings of petitioner Toyota Shaw, Inc. (hereinafter Toyota) and respondent Luna L. Sosa (hereinafter Sosa) are as follows. Sometime in June of 1989, Luna L. Sosa wanted to purchase a Toyota Lite Ace. It was then a seller's market and Sosa had difficulty finding a dealer with an available unit for sale. But upon contacting Toyota Shaw, Inc., he was told that there was an available unit. So on 14 June 1989, Sosa and his son, Gilbert, went to the Toyota office at Shaw Boulevard, Pasig, Metro Manila. There they met Popong Bernardo, a sales representative of Toyota. Sosa emphasized to Bernardo that he needed the Lite Ace not later than 17 June 1989 because he,his family, and abalikbayan guest would use it on 18 June 1989 to go to Marinduque, his home province, where he would celebrate his birthday on the 19th of June. He added that if he does not arrive in his hometown with the new car, he would become a "laughing stock." Bernardo assured Sosa that a unit would be ready for pick up at 10:00 a.m. on 17 June 1989. Bernardo then signed the aforequoted "Agreements Between Mr. Sosa & Popong Bernardo of Toyota Shaw, Inc." It was also agreed upon by the parties that the balance of the purchase price would be paid by credit financing through B.A. Finance, and for this Gilbert, on behalf of his father, signed the documents of Toyota and B.A. Finance pertaining to the application for financing. The next day, 15 June 1989, Sosa and Gilbert went to Toyota to deliver the downpaymentofP100,000.00. They met Bernardo who then accomplished a printed Vehicle Sales Proposal (VSP) No. 928, 2 on which Gilbert signed under the subheading CONFORME. This document shows that the customer's name is "MR. LUNA SOSA" with home address at No. 2316 Guijo Street, United Parañaque II; that the model series of the vehicle is a "Lite Ace 1500" described as "4 Dr minibus"; that payment is by "installment," to be financed by "B.A.," 3 with the initial cash outlay of P100,000.00 broken down as follows: a) downpayment — P 53,148.00 b) insurance — P 13,970.00 c) BLT registration fee — P 1,067.00 CHMO fee — P 2,715.00 service fee — P 500.00 accessories — P 29,000.00 and that the "BALANCE TO BE FINANCED" is "P274,137.00." The spaces provided for "Delivery Terms" were not filled-up. It also contains the following pertinent provisions: CONDITIONS OF SALES 1. This sale is subject to availability of unit. 2. Stated Price is subject to change without prior notice, Price prevailing and in effect at time of selling will apply. . . . Rodrigo Quirante,the Sales Supervisor of Bernardo, checked and approved the VSP. On 17 June 1989, at around 9:30 a.m., Bernardo called Gilbert to inform him that the vehicle would notbe ready for pick up at 10:00 a.m. as previously agreed upon but at 2:00 p.m. that same day. At 2:00 p.m., Sosa and Gilbert met Bernardo at the latter's office. According to Sosa, Bernardo informed them that the Lite Ace was being readied for delivery. After waiting for about an hour, Bernardo told them that the car could not be delivered because "nasulot ang unit ng ibang malakas." Toyota contends, however, that the Lite Ace was not delivered to Sosa because of the disapproval by B.A. Finance of the credit financing application of Sosa. It further alleged that a particular unit had already been reserved and earmarked for Sosa but could not be released due to the uncertainty of payment of the balance of the purchase price. Toyota then gave Sosa the option to purchase the unit by paying the full purchase price in cash but Sosa refused. After it became clear that the Lite Ace would notbe delivered to him, Sosa asked that his downpayment be refunded. Toyota did so on the very same day by issuing a Far EastBank check for the full amountof P100,000.00, 4 the receiptof which was shown by a check voucher of Toyota,5 which Sosa signed with the reservation, "without prejudice to our future claims for damages." Thereafter, Sosa sent two letters to Toyota. In the first letter, dated 27 June 1989 and signed by him, he demanded the refund, within five days from receipt, of the downpayment of P100,000.00 plus interest from the time he paid it and the payment of damages with a warning that in case of Toyota's failure to do so he would be constrained to take legal action. 6 The second, dated 4 November 1989 and signed by M. O. Caballes,Sosa's counsel,demanded one million pesos representing interest and damages,again,with a warning that legal action would be taken if payment was

- 3. 3 not made within three days. 7 Toyota's counsel answered through a letter dated 27 November 1989 8 refusing to accede to the demands of Sosa. But even before this answer was made and received by Sosa, the latter filed on 20 November 1989 with Branch 38 of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Marinduque a complaint against Toyota for damages under Articles 19 and 21 of the Civil Code in the total amount of P1,230,000.00. 9 He alleges, inter alia, that: 9. As a result of defendant's failure and/or refusal to deliver the vehicle to plaintiff, plaintiff suffered embarrassment, humiliation, ridicule, mental anguish and sleepless nights because: (i) he and his family were constrained to take the public transportation from Manila to Lucena City on their way to Marinduque; (ii) his balikbayan-guestcanceled his scheduled firstvisitto Marinduque in order to avoid the inconvenience of taking public transportation; and (iii) his relatives, friends, neighbors and other provincemates, continuously irked him about "his Brand-New Toyota Lite Ace — that never was." Under the circumstances, defendant should be made liable to the plaintifffor moral damages in the amount of One Million Pesos (P1,000,000.00). 10 In its answer to the complaint,Toyota alleged that no sale was entered into between it and Sosa, that Bernardo had no authority to sign Exhibit "A" for and in its behalf, and that Bernardo signed Exhibit "A" in his personal capacity. As special and affirmative defenses, it alleged that: the VSP did not state date of delivery; Sosa had not completed the documents required by the financing company, and as a m atter of policy, the vehicle could not and would not be released prior to full compliance with financing requirements, submission of all documents, and execution of the sales agreement/invoice; the P100,000.00 was returned to and received by Sosa; the venue was improperlylaid;and Sosa did not have a sufficientcause of action against it. It also interposed compulsory counterclaims. After trial on the issues agreed upon during the pre-trial session, 11 the trial court rendered on 18 February 1992 a decision in favor of Sosa. 12 It ruled that Exhibit "A," the "AGREEMENTS BETWEEN MR. SOSA AND POPONG BERNARDO," was a valid perfected contract of sale between Sosa and Toyota which bound Toyota to deliver the vehicle to Sosa, and further agreed with Sosa that Toyota acted in bad faith in selling to another the unit already reserved for him. As to Toyota's contention that Bernardo had no authority to bind it through Exhibit "A," the trial court held that the extent of Bernardo's authority "was not made known to plaintiff," for as testified to by Quirante, "they do not volunteer any information as to the company's sales policy and guidelines because they are internal matters." 13 Moreover, "[f]rom the beginning ofthe transaction up to its consummation when the downpayment was made by the plaintiff, the defendants had made known to the plaintiff the impression that Popong Bernardo is an authorized sales executive as it permitted the latter to do acts within the scope of an apparent authority holding him out to the public as possessing power to do these acts." 14 Bernardo then "was an agent of the defendant Toyota Shaw, Inc. and hence bound the defendants." 15 The court further declared that "Luna Sosa proved his social standing in the community and suffered besmirched reputation, wounded feelings and sleepless nights for which he ought to be compensated." 16 Accordingly, it disposed as follows: WHEREFORE, viewed from the above findings,judgmentis hereby rendered in favor of the plaintiff and against the defendant: 1. ordering the defendant to pay to the plaintiff the sum of P75,000.00 for moral damages; 2. ordering the defendant to pay the plaintiff the sum of P10,000.00 for exemplary damages; 3. ordering the defendant to pay the sum of P30,000.00 attorney's fees plus P2,000.00 lawyer's transportation fare per trip in attending to the hearing of this case; 4. ordering the defendant to pay the plaintiff the sum of P2,000.00 transportation fare per trip of the plaintiff in attending the hearing of this case; and 5. ordering the defendant to pay the cost of suit. SO ORDERED. Dissatisfied with the trial court's judgment, Toyota appealed to the Court of Appeals. The case was docketed as CA-G.R. CV No. 40043.In its decision promulgated on 29 July 1994,17 the Court of Appeals affirmed in toto the appealed decision. Toyota now comes before this Courtvia this petition and raises the core issue stated at the beginning ofthe ponenciaand also the following related issues: (a) whether or not the standard VSP was the true and documented understanding of the parties which would have led to the ultimate contractof sale,(b) whether or not Sosa has any legal and demandable right to the delivery of the vehicle despite the non-payment of the consideration and the non-approval of his credit application by B.A. Finance, (c) whether or not Toyota acted in good faith when it did not release the vehicle to Sosa, and (d) whether or not Toyota may be held liable for damages. We find merit in the petition. Neither logic nor recourse to one's imagination can lead to the conclusion that Exhibit "A" is a perfected contract of sale.

- 4. 4 Article 1458 of the Civil Code defines a contract of sale as follows: Art. 1458. By the contract of sale one of the contracting parties obligates himself to transfer the ownership of and to deliver a determinate thing, and the other to pay therefor a price certain in money or its equivalent. A contract of sale may be absolute or conditional. and Article 1475 specifically provides when it is deemed perfected: Art. 1475.The contract of sale is perfected at the momentthere is a meeting of minds upon the thing which is the object of the contract and upon the price. From that moment, the parties may reciprocally demand performance, subject to the provisions of the law governing the form of contracts. What is clear from Exhibit "A" is not what the trial court and the Court of Appeals appear to see. It is not a contract of sale. No obligation on the part of Toyota to transfer ownership ofa determinate thing to Sosa and no correlative obligation on the part of the latter to pay therefor a price certain appears therein. The provision on the downpayment of P100,000.00 made no specific reference to a sale of a vehicle. If it was intended for a contract of sale, it could only refer to a sale on installment basis, as the VSP executed the following day confirmed. But nothing was mentioned about the full purchase price and the manner the installments were to be paid. This Court had already ruled that a definite agreement on the manner of payment of the price is an essential element in the formation of a binding and enforceable contract of sale. 18 This is so because the agreement as to the manner of payment goes into the price such that a disagreementon the manner of payment is tantamount to a failure to agree on the price.Definiteness as to the price is an essential element of a binding agreement to sell personal property. 19 Moreover, Exhibit "A" shows the absence ofa meeting of minds between Toyota and Sosa. For one thing, Sosa did not even sign it. For another, Sosa was well aware from its title, written in bold letters, viz., AGREEMENTS BETWEEN MR. SOSA & POPONG BERNARDO OF TOYOTA SHAW, INC. that he was not dealing with Toyota but with Popong Bernardo and that the latter did not misrepresent that he had the authority to sell any Toyota vehicle. He knew that Bernardo was only a sales representative of Toyota and hence a mere agent of the latter. It was incumbent upon Sosa to act with ordinary prudence and reasonable diligence to know the extent of Bernardo's authority as an agent20 in respect of contracts to sell Toyota's vehicles. A person dealing with an agent is put upon inquiry and must discover upon his peril the authority of the agent.21 At the most, Exhibit "A" may be considered as part of the initial phase of the generation or negotiation stage of a contract of sale. There are three stages in the contract of sale, namely: (a) preparation, conception, or generation, which is the period of negotiation and bargaining, ending at the moment of agreement of the parties; (b) perfection or birth of the contract, which is the momentwhen the parties come to agree on the terms of the contract; and (c) consummation or death, which is the fulfillment or performance of the terms agreed upon in the contract. 22 The second phase of the generation or negotiation stage in this case was the execution of the VSP. It must be emphasized that thereunder, the downpayment of the purchase price was P53,148.00 while the balance to be paid on installment should be financed by B.A. Finance Corporation. It is, of course, to be assumed that B.A. Finance Corp. was acceptable to Toyota, otherwise itshould nothave mentioned B.A. Finance in the VSP. Financing companies are defined in Section 3(a) of R.A. No. 5980, as amended by P.D. No. 1454 and P.D. No. 1793, as "corporations or partnerships, except those regulated by the Central Bank of the Philippines,the Insurance Commission and the Cooperatives Administration Office, which are primarily organized for the purpose of extending credit facilities to consumers and to industrial, commercial, or agricultural enterprises, either by discounting or factoring commercial papers or accounts receivables, or by buying and selling contracts, leases, chattel mortgages, or other evidence of indebtedness, or by leasing of motor vehicles, heavy equipment and industrial machinery,business and office machines and equipment, appliances and other movable property." 23 Accordingly, in a sale on installmentbasis which is financed by a financing company, three parties are thus involved: the buyer who executes a note or notes for the unpaid balance of the price of the thing purchased on installment,the seller who assigns the notes or discounts them with a financing company, and the financing company which is subrogated in the place of the seller, as the creditor of the installment buyer. 24 Since B.A. Finance did not approve Sosa's application, there was then no meeting of minds on the sale on installment basis.

- 5. 5 We are inclined to believe Toyota's version that B.A. Finance disapproved Sosa's application for which reason it suggested to Sosa that he pay the full purchase price. When the latter refused, Toyota cancelled the VSP and returned to him his P100,000.00. Sosa's version that the VSP was cancelled because, according to Bernardo, the vehicle was delivered to another who was "mas malakas" does not inspire belief and was obviously a delayed afterthought. It is claimed that Bernardo said, "Pasensiya kayo, nasulot ang unit ng ibang malakas," while the Sosas had already been waiting for an hour for the delivery of the vehicle in the afternoon of 17 June 1989. However, in paragraph 7 of his complaint, Sosa solemnly states: On June 17, 1989 at around 9:30 o'clock in the morning, defendant's sales representative, Mr. Popong Bernardo, called plaintiff's house and informed the plaintiff's son that the vehicle will not be ready for pick-up at 10:00 a.m. of June 17, 1989 but at 2:00 p.m. of that day instead. Plaintiff and his son went to defendant's office on June 17 1989 at 2:00 p.m. in order to pick-up the vehicle but the defendant for reasons known only to its representatives, refused and/or failed to release the vehicle to the plaintiff. Plaintiff demanded for an explanation, but nothing was given; . . . (Emphasis supplied). 25 The VSP was a mere proposal which was aborted in lieu of subsequent events. It follows that the VSP created no demandable right in favor of Sosa for the delivery of the vehicle to him,and its non-delivery did not cause any legally indemnifiable injury. The award then of moral and exemplary damages and attorney's fees and costs of suitis withoutlegal basis.Besides, the only ground upon which Sosa claimed moral damages is that since it was known to his friends, townmates, and relatives that he was buying a Toyota Lite Ace which they expected to see on his birthday, he suffered humiliation, shame, and sleepless nights when the van was not delivered. The van became the subject matter of talks during his celebration that he may not have paid for it, and this created an impression againsthis business standing and reputation. At the bottom of this claim is nothing but misplaced pride and ego. He should not have announced his plan to buy a Toyota Lite Ace knowing that he mightnotbe able to pay the full purchase price. It was he who brought embarrassment upon himself by bragging about a thing which he did not own yet. Since Sosa is not entitled to moral damages and there being no award for temperate, liquidated, or compensatory damages, he is likewise not entitled to exemplary damages.Under Article 2229 of the Civil Code, exemplary or corrective damages are imposed by way of example or correction for the public good, in addition to moral, temperate, liquidated, or compensatory damages. Also, it is settled that for attorney's fees to be granted,the court mustexplicitly state in the body of the decision, and not only in the dispositive portion thereof, the legal reason for the award of attorney's fees. 26 No such explicit determination thereon was made in the body of the decision of the trial court. No reason thus exists for such an award. WHEREFORE, the instant petition is GRANTED. The challenged decision of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CV NO. 40043 as well as that of Branch 38 of the Regional Trial Courtof Marinduque in Civil Case No. 89-14 are REVERSED and SET ASIDE and the complaint in Civil Case No. 89-14 is DISMISSED. The counterclaim therein is likewise DISMISSED. No pronouncement as to costs. SO ORDERED. THIRD DIVISION [G.R. No. 138018. July 26, 2002] RIDO MONTECILLO, petitioner, vs. IGNACIA REYNES and SPOUSES REDEMPTOR and ELISA ABUCAY, respondents. D E C I S I O N CARPIO, J.: The Case On March 24, 1993, the Regional Trial Court of Cebu City, Branch 18, rendered a Decision[1] declaring the deed of sale of a parcel of land in favor of petitioner null and void ab initio. The Court of Appeals,[2] in its July 16, 1998 Decision[3] as well as its February 11, 1999 Order[4] denying petitioner’s Motion for Reconsideration, affirmed the trial court’s decision in toto. Before this Court now is a Petition for Review on Certiorari[5] assailing the Court of Appeals’ decision and order. The Facts Respondents Ignacia Reynes (“Reynes” for brevity) and Spouses Abucay (“Abucay Spouses” for brevity) filed on June 20, 1984 a complaint for Declaration of

- 6. 6 Nullity and Quieting of Title against petitioner Rido Montecillo (“Montecillo” for brevity). Reynes asserted that she is the owner of a lot situated in Mabolo, Cebu City, covered by Transfer Certificate of Title No. 74196 and containing an area of 448 square meters (“Mabolo Lot” for brevity). In 1981,Reynes sold 185 square meters of the Mabolo Lot to the Abucay Spouses who built a residential house on the lot they bought. Reynes alleged further that on March 1, 1984 she signed a Deed of Sale of the Mabolo Lot in favor of Montecillo (“Montecillo’s Deed of Sale” for brevity). Reynes, being illiterate,[6] signed by affixing her thumb-mark[7] on the document. Montecillo promised to pay the agreed P47,000.00 purchase price within one month from the signing of the Deed of Sale. Montecillo’s Deed of Sale states as follows: “That I, IGNACIA T. REYNES, of legal age, Filipino,widow,with residence and postal address at Mabolo, Cebu City, Philippines, for and in consideration of FORTY SEVEN THOUSAND (P47,000.00) PESOS, Philippine Currency, to me in hand paid by RIDO MONTECILLO, of legal age, Filipino, married, with residence and postal address at Mabolo, Cebu City, Philippines, the receipt hereof is hereby acknowledged, have sold, transferred, and conveyed, unto RIDO MONTECILLO, his heirs, executors, administrators, and assigns, forever, a parcel of land together with the improvements thereon, situated at Mabolo, Cebu City, Philippines, free from all liens and encumbrances, and more particularly described as follows: A parcel of land (Lot 203-B-2-B of the subdivision plan Psd-07-01-00 2370, being a portion of Lot 203-B-2, described on plan (LRC) Psd-76821, L.R.C. (GLRO) Record No. 5988), situated in the Barrio of Mabolo, City of Cebu. Bounded on the SE., along line 1-2 by Lot 206; on the SW., along line 2-3, by Lot 202, both of Banilad Estate; on the NW., along line 4-5, by Lot 203-B-2-A of the subdivision of Four Hundred Forty Eight (448) square meters, more or less. of which I am the absolute owner in accordance with the provisions of the Land Registration Act, my title being evidenced by Transfer Certificate of Title No. 74196 of the Registry of Deeds of the City of Cebu, Philippines. That This Land Is Not Tenanted and Does Not Fall Under the Purview of P.D. 27.”[8] (Emphasis supplied) Reynes further alleged that Montecillo failed to pay the purchase price after the lapse of the one-month period, prompting Reynes to demand from Montecillo the return of the Deed of Sale. Since Montecillo refused to return the Deed of Sale,[9] Reynes executed a document unilaterally revoking the sale and gave a copy of the document to Montecillo. Subsequently, on May 23, 1984 Reynes signed a Deed of Sale transferring to the Abucay Spouses the entire Mabolo Lot, at the same time confirming the previous sale in 1981 of a 185-square meter portion of the lot. This Deed of Sale states: “I, IGNACIA T. REYNES, of legal age, Filipino, widow and resident of Mabolo, Cebu City, do hereby confirm the sale of a portion of Lot No. 74196 to an extent of 185 square meters to Spouses Redemptor Abucay and Elisa Abucay covered by Deed per Doc. No. 47, Page No. 9, Book No. V, Series of 1981 of notarial register of Benedicto Alo, of which spouses is now in occupation; That for and in consideration of the total sum of FIFTY THOUSAND (P50,000) PESOS, Philippine Currency, received in full and receipt whereof is herein acknowledged from SPOUSES REDEMPTOR ABUCAY and ELISA ABUCAY, do hereby in these presents, SELL, TRANSFER and CONVEY absolutely unto said Spouses Redemptor Abucay and Elisa Abucay, their heirs,assigns and successors- in-interest the whole parcel of land together with improvements thereon and more particularly described as follows: TCT No. 74196 A parcel of land (Lot 203-B-2-B of the subdivision plan psd-07-01-002370, being a portion of Lot 203-B-2, described on plan (LRC) Psd 76821,LRC (GLRO) Record No. 5988) situated in Mabolo, Cebu City, along Arcilla Street, containing an area of total FOUR HUNDRED FORTY EIGHT (448) Square meters. of which I am the absolute owner thereof free from all liens and encumbrances and warrantthe same againstclaim ofthird persons and other deeds affecting said parcel of land other than that to the said spouses and inconsistenthereto is declared without any effect. In witness whereof, I hereunto signed this 23rd day of May, 1984 in Cebu City, Philippines.” [10] Reynes and the Abucay Spouses alleged that on June 18, 1984 they received information that the Register of Deeds of Cebu City issued Certificate of Title No. 90805 in the name of Montecillo for the Mabolo Lot. Reynes and the Abucay Spouses argued that “for lack of consideration there (was) no meeting of the minds”[11] between Reynes and Montecillo. Thus, the trial court should declare null and void ab initio Montecillo’s Deed of Sale, and order the cancellation of Certificate of Title No. 90805 in the name of Montecillo. In his Answer, Montecillo, a bank executive with a B.S. Commerce degree,[12] claimed he was a buyer in good faith and had actually paid the P47,000.00 consideration stated in his Deed of Sale. Montecillo, however, admitted he still owed Reynes a balance of P10,000.00. He also alleged that he paid P50,000.00 for the release of the chattel mortgage which he argued constituted a lien on the Mabolo Lot. He further alleged that he paid for the real property tax as well as the capital gains tax on the sale of the Mabolo Lot. In their Reply, Reynes and the Abucay Spouses contended that Montecillo did not have authority to discharge the chattel mortgage,especially after Reynes revoked Montecillo’s Deed of Sale and gave the mortgagee a copy of the document of revocation. Reynes and the Abucay Spouses claimed that Montecillo secured the release of the chattel mortgage through machination. They further asserted that

- 7. 7 Montecillo took advantage of the real property taxes paid by the Abucay Spouses and surreptitiously caused the transfer of the title to the Mabolo Lot in his name. During pre-trial, Montecillo claimed that the consideration for the sale of the Mabolo Lot was the amount he paid to Cebu Ice and Cold Storage Corporation (“Cebu Ice Storage” for brevity) for the mortgage debt of Bienvenido Jayag (“Jayag” for brevity). Montecillo argued that the release ofthe mortgage was necess ary since the mortgage constituted a lien on the Mabolo Lot. Reynes,however, stated that she had nothing to do with Jayag’s mortgage debt except that the house mortgaged by Jayag stood on a portion of the Mabolo Lot. Reynes further stated that the payment by Montecillo to release the mortgage on Jayag’s house is a matter between Montecillo and Jayag. The mortgage on the house, being a chattel mortgage, could not be interpreted in any way as an encumbrance on the Mabolo Lot. Reynes further claimed thatthe mortgage debt had long prescribed since the P47,000.00 mortgage debt was due for payment on January 30, 1967. The trial court rendered a decision on March 24, 1993 declaring the Deed of Sale to Montecillo null and void. The trial court ordered the cancellation of Montecillo’s Transfer Certificate of Title No. 90805 and the issuance of a new certificate of title in favor of the Abucay Spouses. The trial court found that Montecillo’s Deed of Sale had no cause or consideration because Montecillo never paid Reynes the P47,000.00 purchase price, contrary to what is stated in the Deed of Sale that Reynes received the purchase price. The trial court ruled that Montecillo’s Deed of Sale produced no effect whatsoever for want of consideration. The dispositive portion of the trial court’s decision reads as follows: “WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing consideration, judgment is hereby rendered declaring the deed of sale in favor of defendant null and void and of no force and effect thereby ordering the cancellation of Transfer Certificate of Title No. 90805 of the Register of Deeds of Cebu City and to declare plaintiff Spouses Redemptor and Elisa Abucay as rightful vendees and Transfer Certificate of Title to the property subjectmatter of the suitissued in their names.The defendants are further directed to pay moral damages in the sum of P20,000.00 and attorney’s fees in the sum of P2,000.00 plus cost of the suit. xxx” Not satisfied with the trial court’s Decision,Montecillo appealed the same to the Court of Appeals. Ruling of the Court of Appeals The appellate courtaffirmed the Decision ofthe trial court in toto and dismissed the appeal[13] on the ground that Montecillo’s Deed of Sale is void for lack of consideration. The appellate court also denied Montecillo’s Motion for Reconsideration[14] on the ground that it raised no new arguments. Still dissatisfied, Montecillo filed the present petition for review on certiorari. The Issues Montecillo raises the following issues: 1. “Was there an agreement between Reynes and Montecillo that the stated consideration of P47,000.00 in the Deed of Sale be paid to Cebu Ice and Cold Storage to secure the release of the Transfer Certificate of Title?” 2. “If there was none, is the Deed of Sale void from the beginning or simply rescissible?”[15] The Ruling of the Court The petition is devoid of merit. First issue: manner of payment of the P47,000.00 purchase price. Montecillo’s Deed of Sale does not state that the P47,000.00 purchase price should be paid by Montecillo to Cebu Ice Storage. Montecillo failed to adduce any evidence before the trial court showing thatReynes had agreed, verbally or in writing, that the P47,000.00 purchase price should be paid to Cebu Ice Storage. Absent any evidence showing that Reynes had agreed to the payment of the purchase price to any other party, the payment to be effective must be made to Reynes, the vendor in the sale. Article 1240 of the Civil Code provides as follows: “Payment shall be made to the person in whose favor the obligation has been constituted, or his successor in interest, or any person authorized to receive it.” Thus, Montecillo’s payment to Cebu Ice Storage is not the payment that would extinguish[16] Montecillo’s obligation to Reynes under the Deed of Sale. It militates against common sense for Reynes to sell her Mabolo Lot for P47,000.00 if this entire amount would only go to Cebu Ice Storage, leaving not a single centavo to her for giving up ownership of a valuable property. This incredible allegation ofMontecillo becomes even more absurd when one considers that Reynes

- 8. 8 did not benefit, directly or indirectly, from the payment of the P47,000.00 to Cebu Ice Storage. The trial court found that Reynes had nothing to do with Jayag’s mortgage debt with Cebu Ice Storage. The trial court made the following findings of fact: “x x x. Plaintiff Ignacia Reynes was not a party to nor privy of the obligation in favor of the Cebu Ice and Cold Storage Corporation, the obligation being exclusively of Bienvenido Jayag and wife who mortgaged their residential house constructed on the land subject matter of the complaint. The payment by the defendant to release the residential house from the mortgage is a matter between him and Jayag and cannot by implication or deception be made to appear as an encumbrance upon the land.”[17] Thus,Montecillo’s paymentto Jayag’s creditor could not possiblyredound to the benefit[18] of Reynes. We find no reason to disturb the factual findings of the trial court. In petitions for review on certiorari as a mode of appeal under Rule 45, as in the instant case, a petitioner can raise only questions of law.[19] This Court is not the proper venue to consider a factual issue as it is not a trier of facts. Second issue: whether the Deed of Sale is void ab initio or only rescissible. Under Article 1318 of the Civil Code, “[T]here is no contract unless the following requisites concur: (1) Consent of the contracting parties; (2) Object certain which is the subject matter of the contract; (3) Cause of the obligation which is established.” Article 1352 of the Civil Code also provides that “[C]ontracts without cause x x x produce no effect whatsoever.” Montecillo argues that his Deed of Sale has all the requisites of a valid contract. Montecillo points out that he agreed to purchase, and Reynes agreed to sell, the Mabolo Lot at the price ofP47,000.00. Thus, the three requisites for a valid contract concur: consent,objectcertain and consideration. Montecillo asserts there is no lack of consideration that would prevent the existence of a valid contract. Rather, there is only non-payment of the consideration within the period agreed upon for payment. Montecillo argues there is only a breach of his obligation to pay the full purchase price on time. Such breach merely gives Reynes a right to ask for specific performance, or for annulment of the obligation to sell the Mabolo Lot. Montecillo maintains that in reciprocal obligations, the injured party can choose between fulfillment and rescission,[20] or more properly cancellation, of the obligation under Article 1191[21] of the Civil Code. This Article also provides that the “court shall decree the rescission claimed,unless there be just cause authorizing the fixing of the period.” Montecillo claims that because Reynes failed to make a demand for payment, and instead unilaterally revoked Montecillo’s Deed of Sale, the court has a just cause to fix the period for payment of the balance of the purchase price. These arguments are not persuasive. Montecillo’s Deed of Sale states that Montecillo paid, and Reynes received, the P47,000.00 purchase price on March 1, 1984, the date of signing of the Deed of Sale. This is clear from the following provision of the Deed of Sale: “That I, IGNACIA T. REYNES, x x x for and in consideration of FORTY SEVEN THOUSAND (P47,000.00) PESOS, Philippine Currency, to me in hand paid by RIDO MONTECILLO xxx, receipt of which is hereby acknowledged, have sold, transferred, and conveyed, unto RIDO MONTECILLO, x x x a parcel of land x x x.” On its face, Montecillo’s Deed of Absolute Sale[22] appears supported by a valuable consideration. However, based on the evidence presented by both Reynes and Montecillo, the trial court found that Montecillo never paid to Reynes,and Reynes never received from Montecillo, the P47,000.00 purchase price. There was indisputablya total absence ofconsideration contraryto whatis stated in Montecillo’s Deed of Sale. As pointed out by the trial court – “From the allegations in the pleadings of both parties and the oral and documentary evidence adduced during the trial, the court is convinced that the Deed of Sale (Exhibits “1” and “1-A”) executed by plaintiff Ignacia Reynes acknowledged before Notary Public Ponciano Alvinio is devoid of any consideration. Plaintiff Ignacia Reynes through the representation ofBaudillo Baladjay had executed a Deed of Sale in favor of defendanton the promise thatthe consideration should be paid within one (1) month from the execution of the Deed of Sale. However, after the lapse of said period, defendant failed to pay even a single centavo of the consideration. The answer ofthe defendant did not allege clearly why no consideration was paid by him except for the allegation that he had a balance of only P10,000.00. It turned out during the pre-trial that what the defendant considered as the consideration was the amount which he paid for the obligation of Bienvenido Jayag with the Cebu Ice and Cold Storage Corporation over which plaintiff Ignacia Reynes did not have a part except that the subject of the mortgage was constructed on the parcel of land in question.PlaintiffIgnacia Reynes was not a party to nor privy of the obligation in favor of the Cebu Ice and Cold Storage Corporation, the obligation being exclusively of Bienvenido Jayag and wife who mortgaged their residential house constructed on the land subject matter of the complaint. The payment by the defendant to release the residential house from the mortgage is a matter between him and Jayag and cannot by implication or deception be made to appear as an encumbrance upon the land. “[23] Factual findings of the trial court are binding on us, especially if the Court of Appeals affirms such findings.[24] We do not disturb such findings unless the evidence on record clearly does not support such findings or such findings are based on a patent misunderstanding of facts,[25] which is not the case here. Thus, we find no reason to deviate from the findings of both the trial and appellate courts that no valid consideration supported Montecillo’s Deed of Sale. This is not merely a case of failure to pay the purchase price, as Montecillo claims,which can only amountto a breach of obligation with rescission as the proper remedy. What we have here is a purported contract that lacks a cause - one of the three essential requisites of a valid contract. Failure to pay the consideration is

- 9. 9 different from lack of consideration. The former results in a right to demand the fulfillmentor cancellation ofthe obligation under an existing valid contract[26] while the latter prevents the existence of a valid contract Where the deed of sale states that the purchase price has been paid but in fact has never been paid, the deed of sale is null and void ab initio for lack of consideration. This has been the well-settled rule as early as Ocejo Perez & Co. v. Flores,[27] a 1920 case. As subsequently explained in Mapalo v. Mapalo[28] – “In our view, therefore, the ruling of this Court in Ocejo Perez & Co. vs. Flores, 40 Phil. 921, is squarely applicable herein. In that case we ruled that a contract of purchase and sale is null and void and produces no effect whatsoever where the same is without cause or consideration in that the purchase price which appears thereon as paid has in fact never been paid by the purchaser to the vendor.” The Court reiterated this rule in Vda. De Catindig v. Heirs of Catalina Roque,[29] to wit – “The Appellate Court’s finding that the price was not paid or that the statement in the supposed contracts of sale (Exh. 6 to 26) as to the payment of the price was simulated fortifies the view that the alleged sales were void. “If the price is simulated, the sale is void . . .” (Art. 1471, Civil Code) A contract of sale is void and produces no effect whatsoever where the price, which appears thereon as paid, has in fact never been paid by the purchaser to the vendor (Ocejo, Perez & Co. vs. Flores and Bas, 40 Phil. 921; Mapalo vs. Mapalo, L-21489, May 19, 1966, 64 O.G. 331, 17 SCRA 114, 122). Such a sale is non-existent (Borromeo vs. Borromeo, 98 Phil. 432) or cannot be considered consummated (Cruzado vs. Bustos and Escaler, 34 Phil. 17; Garanciang vs. Garanciang, L-22351, May 21, 1969, 28 SCRA 229).” Applying this well-entrenched doctrine to the instant case, we rule that Montecillo’s Deed of Sale is null and void ab initio for lack of consideration. Montecillo asserts thatthe only issue in controversy is “the mode and/or manner of payment and/or whether or not payment has been made.”[30] Montecillo implies that the mode or manner of payment is separate from the consideration and does not affect the validity of the contract. In the recent case of San Miguel Properties Philippines, Inc. v. Huang,[31] we ruled that – “In Navarro v. Sugar Producers Cooperative Marketing Association, Inc. (1 SCRA 1181 [1961]), we laid down the rule that the manner of payment of the purchase price is an essential element before a valid and binding contract of sale can exist. Although the Civil Code does not expressly state that the minds of the parties mustalso meeton the terms or manner of payment of the price, the same is needed, otherwise there is no sale. As held in Toyota Shaw, Inc. v. Court of Appeals (244 SCRA 320 [1995]), agreement on the manner of payment goes into the price such that a disagreement on the manner of payment is tantamount to a failure to agree on the price.” (Emphasis supplied) One of the three essential requisites of a valid contract is consent of the parties on the objectand cause of the contract. In a contract of sale,the parties must agree not only on the price, but also on the manner of payment of the price. An agreement on the price but a disagreement on the manner of its payment will not result in consent, thus preventing the existence of a valid contract for lack of consent. This lack of consent is separate and distinct from lack of consideration where the contract states that the price has been paid when in fact it has never been paid. Reynes expected Montecillo to pay him directly the P47,000.00 purchase price within one month after the signing of the Deed of Sale. On the other hand, Montecillo thoughtthat his agreementwith Reynes required him to pay the P47,000.00 purchase price to Cebu Ice Storage to settle Jayag’s mortgage debt. Montecillo also acknowledged a balance of P10,000.00 in favor of Reynes although this amount is not stated in Montecillo’s Deed of Sale. Thus, there was no consent, or meeting of the minds, between Reynes and Montecillo on the manner of payment. This prevented the existence of a valid contract because of lack of consent. In summary,Montecillo’s Deed of Sale is null and void ab initio not only for lack of consideration, but also for lack of consent. The cancellation of TCT No. 90805 in the name of Montecillo is in order as there was no valid contract transferring ownership of the Mabolo Lot from Reynes to Montecillo. WHEREFORE, the petition is DENIED and the assailed Decision dated July 16, 1998 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CV No. 41349 is AFFIRMED. Costs against petitioner. SO ORDERED. Puno, (Chairman), Panganiban, and Sandoval-Gutierrez, JJ., concur. Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila SECOND DIVISION G.R. No. L-27829 August 19, 1988 PHILIPPINE VIRGINIA TOBACCO ADMINISTRATION, petitioner, vs. HON. WALFRIDO DE LOS ANGELES, Judge of the Court of First Instance of Rizal, Branch IV (Quezon City) and TIMOTEO A. SEVILLA, doing business under the name and style of PHILIPPINE ASSOCIATED RESOURCES and PRUDENTIAL BANK AND TRUST COMPANY, respondents.

- 10. 10 Lorenzo F. Miravite for respondent Timoteo Sevilla. Ferrer & Ranada Law Office for respondent Prudential Bank & Trust Co. PARAS, J.: In these petition and supplemental petition for Certiorari, Prohibition and mandamus with Preliminary Injunction, petitioner Philippine Virginia Tobacco Administration seeks to annul and setaside the following Orders ofrespondentJudge of the Court of First Instance of Rizal, Branch IV (Quezon City) in Civil Case No. Q-10351 and prays that the Writ of Preliminary Injunction (that may be) issued by this Court enjoining enforcement of the aforesaid Orders be made permanent. (Petition, Rollo, pp. 1-9) They are: The Order of July 17, 1967: AS PRAYED FOR, the Prudential Bank & Trust Company is hereby directed to release and deliver to the herein plaintiff, Timoteo A. Sevilla, the amount of P800,000.00 in its custody representing the marginal depositofthe Letters of Credit which said bank has issued in favor of the defendant, upon filing by the plaintiff of a bond in the um of P800,000.00, to answer for whatever damage that the defendant PVTA and the Prudential Bank & Trust Company may suffer by reason of this order. (Annex "A," Rollo, p. 12) The Order of November 3,1967: IN VIEW OF THE FOREGOING, the petition under consideration is granted, as follows: (a) the defendant PVTA is hereby ordered to issue the corresponding certificate of Authority to the plaintiff, allowing him to export the remaining balance of his tobacco quota at the current world market price and to make the corresponding import of American high-grade tobacco; (b) the defendant PVTA is hereby restrained from issuing any Certificate of Authority to export or import to any persons and/or entities while the right of the plaintiff to the balance of his quota remains valid, effective and in force; and (c) defendant PVTA is hereby enjoined from opening public bidding to sell its Virginia leaf tobacco during the effectivity of its contract with the plaintiff. xxx xxx xxx In order to protect the defendant from whatever damage it may sustain byvirtue of this order, the plaintiff is hereby directed to file a bond in the sum of P20,000.00. (Annex "K," Rollo, pp. 4-5) The Order of March 16, 1968: WHEREFORE, the motion for reconsideration of the defendant against the order of November 3, 1967 is hereby DENIED. (Annex "M," Rollo, P. 196) The facts of the case are as follows: Respondent Timoteo Sevilla, proprietor and General Manager of the Philippine Associated Resources (PAR) together with two other entities,namely,the Nationwide Agro-Industrial Development Corp. and the Consolidated Agro-Producers Inc. were awarded in a public bidding the right to import Virginia leaf tobacco for blending purposes and exportation by them of PVTA and farmer's low-grade tobacco at a rate of one (1) kilo of imported tobacco for every nine (9) kilos of leaf tobacco actually exported. Subsequently, the other two entities assigned their rights to PVTA and respondent remained the only private entity accorded the privilege. The contract entered into between the petitioner and respondent Sevilla was for the importation of85 million kilos ofVirginia leaf tobacco and a counterpart exportation of 2.53 million kilos of PVTA and 5.1 million kilos of farmer's and/or PVTA at P3.00 a kilo. (Annex "A," p. 55 and Annex "B," Rollo, p. 59) In accordance with their contract respondentSevilla purchased from petitioner and actuallyexported 2,101.470 kilos of tobacco, paying the PVTA the sum of P2,482,938.50 and leaving a balance of P3,713,908.91. Before respondent Sevilla could import the counterpart blending Virginia tobacco, amounting to 525,560 kilos,Republic Act No. 4155 was passed and took effect on June 20, 1 964, authorizing the PVTA to grant import privileges at the ratio of 4 to 1 instead of 9 to 1 and to dispose of all its tobacco stock at the best price available. Thus, on September 14, 1965 subject contract which was already amended on December 14, 1963 because of the prevailing export or world market price under which respondent will be exporting at a loss, (Complaint, Rollo, p. 3) was further amended to grant respondent the privileges under aforesaid law, subject to the following conditions:(1) that on the 2,101.470 kilos already purchased, and exported, the purchase price ofabout P3.00 a kilo was maintained; (2) that the unpaid balance of P3,713,908.91 was to be liquidated by paying PVTA the sum of P4.00 for every kilo of imported Virginia blending tobacco and; (3) that respondent Sevilla would open an irrevocable letter of credit No. 6232 with the Prudential Bank and Trust Co. in favor of the PVTA to secure the payment of said balance,drawable upon the release from the Bureau of Customs of the imported Virginia blending tobacco. While respondentwas trying to negotiate the reduction of the procurement cost of the 2,101.479 kilos of PVTA tobacco already exported which attempt was denied by

- 11. 11 petitioner and also by the Office of the President, petitioner prepared two drafts to be drawn against said letter of credit for amounts which have already become due and demandable. Respondent then filed a complaint for damages with preliminary injunction against the petitioner in the amount of P5,000,000.00. Petitioner filed an answer with counterclaim, admitting the execution of the contract. It alleged however that respondent,violated the terms thereofby causing the issuance of the preliminary injunction to prevent the former from drawing from the letter of credit for amounts due and payable and thus caused petitioner additional damage of 6% per annum. A writ of preliminary injunction was issued by respondent judge enjoining petitioner from drawing against the letter of credit. On motion of respondent, Sevilla, the lower court dismissed the complainton April 19, 1967 withoutprejudice and lifted the writ of preliminaryinjunction butpetitioner's motion for reconsideration was granted on June 5,1967 and the Order of April 19,1967 was set aside. On July 1, 1967 Sevilla filed an urgent motion for reconsideration of the Order of June 5, 1967 praying that the Order of dismissal be reinstated. But pending the resolution of respondent's motion and without notice to the petitioner, respondent judge issued the assailed Order of July 17, 1967 directing the Prudential Bank & Trust Co. to make the questioned release of funds from the Letter of Credit. Before petitioner could file a motion for reconsideration of said order, respondent Sevilla was able to secure the releaseof P300,000.00 and the rest of the amount. Hence this petition, followed by the supplemental petition when respondent filed with the lower court an urgent ex-parte petition for the issuance of preliminary mandatory and preventive injunction which was granted in the resolution of respondent Judge on November 3, 1967, above quoted. On March 16, 1968, respondent Judge denied petitioner's motion for reconsideration. (Supp. Petition, Rollo, pp. 128- 130) Pursuant to the resolution of July 21, 1967, the Supreme Court required respondent to file an answer to the petition within 10 days from notice thereof and upon petitioner's posting a bond of fifty thousand pesos (P50,000.00), a writ of preliminary mandatory injunction was issued enjoining respondent Judge from enforcing and implementing his Order of July 17,1967 and private respondents Sevilla and Prudential Bank and Trust Co. from complying with and implementing said order. The writ further provides that in the event that the said order had already been complied with and implemented,said respondents are ordered to return and make available the amounts that might have been released and taken delivery of by respondent Sevilla. (Rollo, pp. 16-17) In its answer, respondent bank explained that when it received the Order of the Supreme Courtto stop the release of P800,000.00 it had already released the same in obedience to ailieged earlier Order of the lower Court which was reiterated with ailieged admonition in a subsequent Order. (Annex "C," Rollo, pp. 37-38) A Manifestation to that effect has already been filed c,irrency respondent bank (Rollo, pp. 19-20) which was noted c,irrency this Court in the resolution of August 1, 1967, a copy of which was sent to the Secretary of Justice. (Rollo, p. 30) Before respondent Sevilla could file his answer, petitioner filed a motion to declare him and respondent bank in contempt of court for having failed to comply with the resolution to this court of July 21, 1967 to the effect that the assailed order has already been implemented but respondents failed to return and make available the amounts that had been released and taken delivery of by respondent Sevilla. (Rollo, pp. 100-102) In his answer to the petition, respondentSevilla claims thatpetitioner demanded from him a much higher price for Grades D and E tobacco than from the other awardees; that petitioner violated its contract by granting indiscriminately to numerous buyers the right to export and import tobacco while his agreement is being implemented, thereby depriving respondent of his exclusive right to import the Virginia leaf tobacco for blending purposes and that respondent Judge did not abuse his discretion in ordering the release ofthe amount of P800,000.00 from the Letter of Credit, upon his posting a bond for the same amount. He argued further that the granting of said preliminaryinjunction is within the sound discretion of the court with or without notice to the adverse party when the facts and the law are clear as in the instant case. He insists that petitioner caretaker.2 claim from him a price higher than the other awardees and thatpetitioner has no more right to the sum in controversy as the latter has alreadybeen overpaid when computed not at the price of tobacco provided in the contract which is inequitable and therefore null and void but at the price fixed for the other awardees. (Answer of Sevilla, Rollo, pp. 105-111) In its Answer to the Motion for Contempt,respondentbank reiterates its allegations in the Manifestation and Answer which it filed in this case. (Rollo, pp. 113-114) In his answer, (Rollo, pp. 118-119) to petitioner's motion to declare him in contempt, respondent Sevilla explains that when he received a copy of the Order of this Court, he had already disbursed the whole amountwithdrawn,to settle his huge obligations. Later he filed a supplemental answer in compliance with the resolution ofthis Court of September 15,1967 requiring him to state in detail the amounts allegedly disbursed c,irrency him out of the withdrawn funds. (Rollo, pp. 121-123) Pursuant to the resolution of the Supreme Court on April 25, 1968, a Writ of Preliminary Injunction was issued upon posting of a surety bond in the amount of twenty thousand pesos (P20,000.00) restraining respondent Judge from enforcing and implementing his orders of November 3, 1967 and March 16, 1968 in Civil Case No. Q-10351 of the Court of First Instance of Rizal (Quezon City). RespondentSevilla filed an answer to the supplemental petition (Rollo, pp. 216-221) and so did respondent bank (Rollo, p. 225). Thereafter, all the parties filed their respective memoranda (Memo for Petitioners, Rollo, pp. 230-244 for Resp. Bank, pp. 246-247;and for Respondents,Rollo,pp.252-257).Petitioners filed a rejoinder (rollo, pp. 259-262) and respondent Sevilla filed an Amended Reply Memorandum (Rollo, pp. 266274). Thereafter the case was submitted for decision:' in September, 1968 (Rollo, p. 264). Petitioner has raised the following issues:

- 12. 12 1. RespondentJudge acted withoutor in excess of jurisdiction or with grave abuse of discretion when he issued the Order of July 17, 1967, for the following reasons: (a) the letter of credit issued by respondent bank is irrevocable; (b) said Order was issued withoutnotice and (c) said order disturbed the status quo of the parties and is tantamount to prejudicing the case on the merits. (Rollo, pp. 7-9) 2. RespondentJudge likewise acted without or in excess of jurisdiction or with grave abuse of discretion when he issued the Order of November 3, 1967 which has exceeded the proper scope and function of a Writ of PreliminaryInjunction which is to preserve the status quo and caretaker.2 therefore assume without hearing on the merits,that the award granted to respondentis exclusive;that the action is for specific performance a d that the contract is still in force; that the conditions of the contract have already been complied with to entitle the party to the issuance of the corresponding Certificate ofAuthority to importAmerican high grade tobacco; that the contract is still existing; that the parties have already agreed that the balance of the quota of respondentwill be sold at current world market price and that petitioner has been overpaid. 3. The alleged damages suffered and to be suffered by respondent Sevilla are not irreparable,thus lacking in one essential prerequisite to be established before a Writ of PreliminaryInjunction maybe issued.The alleged damages to be suffered are loss of expected profits which can be measured and therefore reparable. 4. Petitioner will suffer greater damaaes than those alleged by respondent if the injunction is not dissolved. Petitioner stands to lose warehousing storage and servicing fees amounting to P4,704.236.00 yearly or P392,019.66 monthly, not to mention the loss of opportunity to take advantage of any beneficial change in the price of tobacco. 5. The bond fixed by the lower court, in the amount of P20,000.00 is grossly inadequate, (Rollo, pp. 128-151) The petition is impressed with merit. In issuing the Order of July 17, 1967, respondent Judge violated the irrevocability of the letter of credit issued by respondent Bank in favor of petitioner. An irrevocable letter of credit caretaker.2 during its lifetime be cancelled or modified Without the express permission of the beneficiary (Miranda and Garrovilla, Principles of Money Creditand Banking,Revised Edition, p. 291). Consequently, if the finding agricul- the trial on the merits is that respondent Sevilla has ailieged unpaid balance due the petitioner, such unpaid obligation would be unsecured. In the issuance ofthe aforesaid Order, respondentJudge likewise violated: Section 4 of Rule 15 of the Relatiom, Rules of Court which requires that notice of a motion be served by the applicantto all parties concerned atleastthree days before the hearing thereof; Section 5 of the same Rule which provides thatthe notice shall be directed to the parties concerned; and shall state the time and place for the hearing of the motion; and Section 6 of the same Rule which requires proof of service of the notice thereof, except when the Court is satisfied that the rights of the adverse party or parties are not affected, (Sunga vs. Lacson,L-26055,April 29, 1968, 23 SCRA 393) A motion which does not meet the requirements of Sections 4 and 5 of Rule 15 of the Relatiom, Rules of Court is considered a worthless piece of paper which the Clerk has no right to receiver and the respondent court a quo he has no authority to act thereon. (Vda. de A. Zarias v. Maddela, 38 SCRA 35; Cledera v. Sarn-j-iento, 39 SCRA 552; and Sacdalan v. Bautista, 56 SCRA 175). The three-day notice required by law in the filing of a motion is intended not for the movant's benefit but to avoid surprises upon the opposite party and to give the latter time to study and meet the arguments of the motion. (J.M. Tuason and Co., Inc. v. Magdangal, L-1 5539. 4 SCRA 84). More specifically, Section 5 of Rule 58 requires notice to the defendant before a preliminaryinjunction is granted unless it shall appear from facts shown bv affidavits or by the verified complaintthatgreat or irreparable injury would result to the applyin- before the matter can be heard on notice. Once the application is filed with the Judge, the latter must cause ailieged Order to be served on the defendant, requiring him to show cause at a given time and place why the injunction should not be granted. The hearing is essential to the legality of the issuance of a preliminary injunction. It is ailieged abuse ofdiscretion on the part of the court to issue ailieged injunction without hearing the parties and receiving evidence thereon (Associated Watchmen and Security Union, et al. v. United States Lines, et al., 101 Phil. 896). In the issuance of the Order of November 3, 1967, with notice and hearing notwithstanding the discretionary power of the trial court to Issue a preliminary mandatoryinjunction is notabsolute as the issuance ofthe writ is the exception rather than the rule.The party appropriate for it mustshow a clear legal right the violation of which is so recent as to make its vindication an urgent one (Police Commission v. Bello,37 SCRA 230).It -is granted only on a showing that (a) the invasion of the right is material and substantial;(b) the rightof the complainantis clear and unmistakable; and (c) there is ailieged urgent and permanent necessity for the writ to prevent serious decision ( Pelejo v. Court of Appeals, 117 SCRA 665). In fact, it has always been said that it is improper to issue a writ of preliminarymandatoryinjunction prior to the final hearing except in cases of extreme urgency, where the right of petitioner to the writ is very clear; where considerations of relative inconvenience bear strongly in complainant's favor; where there is a willful and unlawful invasion of plaintiffs right against his protest and remonstrance the injury being a contributing one, and there the effect of the mandatory injunctions is rather to re-establish and maintain a pre- existing continuing relation between the parties, recently and arbitrarily interrupted c,irrency the defendant,than to establish a new relation (Alvaro v. Zapata, 11 8 SCRA 722; Lemi v. Valencia,February 28, 1963,7 SCRA 469; Com.of Customs v. Cloribel, L-20266, January 31, 1967,19 SCRA 234. In the case at bar there appears no urgency for the issuance of the writs of preliminary mandatory injunctions in the Orders of July 17, 1967 and November 3, 1967; much less was there a clear legal right of respondent Sevilla that has been violated by petitioner. Indeed, it was ailieged abuse of discretion on the part of

- 13. 13 respondent Judge to order the dissolution of the letter of credit on the basis of assumptions that cannot be established except by a hearing on the merits nor was there a showing that R.A. 4155 applies retroactively to respondent in this case, modifying his importation / exportation contract with petitioner. Furthermore, a writ of preliminary injunction's enjoining any withdrawal from Letter of Credit 6232 would have been sufficient to protect the rights of respondent Sevilla should the finding be that he has no more unpaid obligations to petitioner. Similarly,there is meritin petitioner's contention that the question of exclusiveness of the award is ailieged issue raised by the pleadings and therefore a matter of controversy, hence a preliminary mandatory injunction directing petitioner to issue respondent Sevilla a certificate of authority to import Virginia leaf tobacco and at the same time restraining petitioner from issuing a similar certificate of authority to others is premature and improper. The sole objectof a preliminaryinjunction is to preserve the status quo until the merit can be heard. It is the last actual peaceable uncontested status which precedes the pending controversy (Rodulfo v. Alfonso, L-144, 76 Phil. 225), in the instant case, before the Case No. Q-10351 was filed in the Court of First Instance of Rizal. Consequently,instead of operating to preserve the status quo until the parties' rights can be fairly and fully investigated and determined (De los Reyes v. Elepano, et al., 93 Phil. 239), the Orders of July 17, 1966 and March 3, 1967 serve to disturb the status quo. Injury is considered irreparable if it is of such constant and frequent recurrence that no fair or reasonable redress can be had therefor in a court of law (Allundorff v. Abrahanson,38 Phil. 585) or where there is no standard c,irrency which their amount can be measured with reasonable accuracy, that is, it is not susceptible of mathematical computation (SSC v. Bayona, et al., L-13555, May 30, 1962). Any alleged damage suffered or might possibly be suffered by respondent Sevilla refers to expected profits and claimed by him in this complaint as damages in the amount of FIVE Million Pesos (P5,000,000.00), a damage that can be measured, susceptible ofmathematical computation,notirreparable,nor do they necessitate the issuance of the Order of November 3, 1967. Conversely, there is truth in petitioner's claim that it will suffer greater damage than that suffered by respondent Sevilla if the Order of November 3, 1967 is not annulled. Petitioner's stock if not made available to other parties will require warehouse storage and servicing fees in the amountof P4,704,236.00 yearly or more than P9,000.000.00 in two years time. Parenthetically, the alleged insufficiency of a bond fixed by the Court is not by itself ailieged adequate reason for the annulmentofthe three assailed Orders. The filing of ailieged insufficient or defective bond does not dissolve absolutely and unconditionally ailieged injunction. The remedy in a proper case is to order party to file a sufficient bond (Municipality of La Trinidad v. CFI of Baguio - Benguet, Br. I, 123 SCRA 81). However, in the instant case this remedy is not sufficient to cure the defects already adverted to. PREMISES CONSIDERED, the petition is given due course and the assailed Orders of July 17, 1967 and November 3, 1967 and March 16, 1968 are ANNULLED and SET ASIDE; and the preliminary injunctions issued c,irrency this Court should continue until the termination of Case No. Q-10351 on the merits. SO ORDERED, THIRD DIVISION [G.R. No. 111743. October 8, 1999] VISITACION GABELO, ERLINDA ABELLA, PETRA PEREZ, ERLINDA TRAQUENA, BEN CARDINAL, EDUARDO TRAQUENA, LEOPOLDO TRAQUENA, MARIFE TUBALAS, ULYSIS MATEO, JOCELYN FERNANDEZ, ALFONSO PLACIDO, LEONARDO TRAQUENA, SUSAN RENDON AND MATEO TRINIDAD, petitioners, vs. COURT OF APPEALS, URSULA MAGLENTE, CONSOLACION BERJA, MERCEDITA FERRER, THELMA ABELLA, ANTONIO NGO, and PHILIPPINE REALTY CORPORATION, respondents. D E C I S I O N PURISIMA, J.: This is a Petition for Review on Certiorari under Rule 45 of the Revised Rules of Court, of the decision of the Court of Appeals, dated April 29, 1993, in CA-G.R. CV No. 33178,affirming the decision of the Regional Trial Court of Manila, Branch 38, in Civil Case No.89-48057,entitled “Philippine Realty Corporation vs. Ursula Maglente, et al.”, declaring the defendants (herein respondents) as the rightful party to purchase the land under controversy, and ordering the plaintiff, Philippine Realty Corporation (PRC, for brevity), to execute the corresponding Contract of Sale/Contract to Sell in favor of the defendants aforenamed. The antecedent facts culminating in the filing of the present petition are as follows: On January 15, 1986, Philippine RealtyCorporation,owner ofa parcel of land at 400 Solana Street, Intramuros, Manila, with an area of 675.80 square meters, and covered by Transfer Certificate of Title No. 43989, entered into a Contract of Lease thereover with the herein private respondent, Ursula Maglente. The lease was for a

- 14. 14 period of three (3) years at a monthly rental of P3,000.00 during the first year, P3,189.78 per month in the second year and P3,374.00 monthly for the third year. The lease contract stipulated: “12. That the LESSOR shall have the right to sell any part of the entire leased land for any amount or consideration it deems convenient, subject to the condition, however, that the LESSEE shall be notified about it sixty (60) days in advance; that the LESSEE shall be given the first priority to buy it; and in the event that the LESSEE cannot afford to buy, the final buyer shall respect this lease for the duration of the same, except in cases of exproriation.” It also prohibited the lessee to “cede, transfer, mortgage, sublease or in any manner encumber the whole or part of the leased land and its improvements or its rights as LESSEE of the leased land, without the previous consent in writing of the LESSOR contained in a public instrument.” However, after the execution of the lease agreement, respondent Maglente started leasing portions ofthe leased area to the herein petitioners,Visitacion Gabelo, Erlinda Abella, Petra Perez, Erlinda Traquena, Ben Cardinal, Eduardo Traquena, Leopoldo Traquena, Marife Tubalas, Ulysis Mateo, Jocelyn Fernandez, Alfonso Placido, Leonardo Traquena, Susan Rendon and Mateo Trinidad, who erected their respective houses thereon. On March 9, 1987, when the lease contract was about to expire, the Philippine Realty Corporation, through its Junior Trust and Property Officers, Mr. Leandro Buguis and Mr. Florentino B. Rosario, sent a written offer to sell subject properties to respondent Ursula Maglente. The said letter stated: “We wish to inform you that the Archdiocese of Manila has now decided to open for sale the properties it own (sic) in the District of Intramuros, Manila. However, before we acccept offers from other parties we are of course giving the first priority to our tenants or lessees of Intramuros lots.” Responding to such written offer, Maglente wrote a letter, dated February 2, 1988, to the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Manila manifesting an intention to exercise her right of first priority to purchase the property as stipulated in the lease contract. On February 15, 1988,a Memorandum on the offer of Maglente to purchase the property was prepared and presented to Msgr. Domingo Cirilos, president of Philippine Realty Corporation, at the offered price ofP1,800.00 per square meter or for a total amount of P1,216,440.00, with a downpayment of P100,000.00; the balance of the purchase price payable within ten (10) years with interest at the rate of eighteen (18%) percent per annum. Msgr. Cirilos found the offer acceptable and approved the same. On May 11, 1988, Maglente gave a partial downpaym ent of P25,000.00 and additional P25,000.00 on May 20, 1988. In a letter, dated January 28, 1989, Maglente informed the said corporation that there were other persons who were her co-buyers, actually occupying the premises, namely: Consolacion Berja, Mercedita Ferrer, Thelma Abella and Antonio Ngo within their respective areas of 100, 50, 60 and 400 square meters. On January 30, 1989 Maglente paid her back rentals of P60,642.16 and P50,000.00 more, to complete her downpayment of P100,000.00. On February 1989,Philippine RealtyCorporation (PRC) received copy of a letter sent by the herein petitioners to the Archbishop of Manila, Jaime Cardinal Sin, expressing their desire to purchase the portions of subject property on which they have been staying for a long time. And so, PRC met with the petitioners who apprised the corporation of their being actual occupants of the leased premises and of the impending demolition of their houses which Maglente threatened to cause. Petitioners then asked PRC to prevent the demolition of their houses which might result in trouble and violence. On February 23, 1989,in order to resolve which group has the right to purchase subjectproperty as between the petitioners/sublessees of Maglente, and respondent Maglente, and her co-buyers, PRC brought a Complaint in Interpleader against the herein petitioners and private respondents, docketed as Civil Case No. 89-48057 before Branch 38 of the Regional Trial Court of Manila. On March 11, 1991, after trial on the merits, the lower court of origin rendered judgment in favor of respondent Maglente and her group, disposing thus: “WHEREFORE, premises considered, judgment is hereby rendered as follows: 1. Declaring the defendants Ursula Maglente, Consolacion Berja, Mercedita Ferrer, Thelma Abella and Antonio Ngo as the rightful party to purchase the land in controversy; and 2. Ordering plaintiff Philippine Realty Corporation to execute the corresponding contract of sale/contract to sell in favor of the defendants aforementioned in accordance with this Decision within thirty (30) days from notice thereof.” Dissatisfied with the aforesaid decision below, the Gabelo group (petitioners here) appealed to the Court of Appeals, which affirmed the disposition of the trial court appealed from. Undaunted, petitioners found their way to this Court via the present petition, assigning as sole error the ruling of the Court of Appeals upholding the right of the private respondents, Consolacion Berja and Antonio Ngo, to purchase subject property. Petitioners theorize that they are tenants of Ursula Maglente on the land in dispute, which they are occupying, and as such actual occupants they have the preferential right to purchase the portions of land respectively occupied by them; that the private respondents,Thelma Abella and Antonio Ngo,have never been occupants of the contested lot, and that, as defined in the Pre-trial Order[1] issued below, the issue for resolution should have been limited to whether or not Berja and Ngo actually

- 15. 15 occupied the premises in question because occupation thereon is the basis of the right to purchase subject area. Petitioners’ contention is untenable. There is no legal basis for the assertion by petitioners that as actual occupants of the said property, they have the right of first priority to purchase the same. As regards the freedom of contract, it signifies or implies the rightto choose with whom to contract. PRC is thus free to offer its subject property for sale to any interested person. It is not duty bound to sell the same to the petitioners simply because the latter were in actual occupation of the property absent any prior agreementvesting in them as occupants the right of first priority to buy, as in the case of respondent Maglente. As a matter of fact, because it (PRC) contracted only with respondent Maglente, it could even evict the petitioners from the premises occupied by them considering that the sublease contract between petitioners and Maglente was inked without the prior consent in writing of PRC, as required under the lease contract. Thus, although the other private respondents were not parties to the lease contract between PRC and Maglente, the former could freely enter into a contract with them. So also, the contract of sale having been perfected, the parties thereto are already bound thereby and petitioners can no longer assert their right to buy. It is well-settled that a contract of sale is perfected the moment there is a meeting of the minds ofthe contracting parties upon the thing which is the object of the contract and upon the price.[2] From the time a party accepts the other party’s offer to sell within the stipulated period without qualification, a contract of sale is deemed perfected.[3] In the case under consideration, the contract of sale was already perfected - PRC offered the subjectlot for sale to respondentMaglente and her group through its Junior Trust and Property Officers. Respondent Maglente and her group accepted such offer through a letter addressed to the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Manila, dated February 2, 1988, manifesting their intention to purchase the property as provided for under the lease contract. Thus, there was already an offer and acceptance giving rise to a valid contract. As a matter of fact, respondents have already completed payment of their downpayment of P100,000.00. Therefore, as borne by evidence on record, the requisites under Article 1318 of the Civil Code[4] for a perfected contract have been met. Anent petitioners’ submission thatthe sale has not been perfected because the parties have not affixed their signatures thereto, suffice it to state that under the law, the meeting ofthe minds between the parties gives rise to a binding contractalthough they have not affixed their signatures to its written form.[5] WHEREFORE, the petition is hereby DENIED for lack of merit and the decision of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CV No. 33178 AFFIRMED. No pronouncementas to costs. SO ORDERED. SECOND DIVISION HEIRS OF CAYETANO PANGAN and CONSUELO PANGAN,* Petitioners, - versus - SPOUSES ROGELIO PERRERAS and PRISCILLA PERRERAS, Respondents. G.R. No. 157374 Present: QUISUMBING, J., Chairperson, CARPIO-MORALES, BRION, DEL CASTILLO, and ABAD, JJ. Promulgated: August 27, 2009 x ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------x D E C I S I O N BRION, J.: The heirs[1] of spouses Cayetano and Consuelo Pangan (petitioners-heirs) seek the reversal of the Court of Appeals’ (CA) decision[2] of June 26, 2002, as well its resolution of February 20, 2003, in CA-G.R. CV Case No. 56590 through the presentpetition for review on certiorari.[3] The CA decision affirmed the Regional Trial Court’s (RTC) ruling[4] which granted the complaint for specific performance filed by spouses Rogelio and Priscilla Perreras (respondents) against the petitioners-heirs, and dismissed the complaint for consignation instituted by Consuelo Pangan (Consuelo) against the respondents. THE FACTUAL ANTECEDENTS The spouses Pangan were the owners of the lot and two-door apartment (subject properties) located at 1142 Casañas St., Sampaloc, Manila.[5] On June 2, 1989,Consuelo agreed to sell to the respondents the subject properties for the price