ORIGINAL ARTICLEThe Health Care Value TransparencyMovement.docx

- 1. ORIGINAL ARTICLE The Health Care Value Transparency Movement and Its Implications for Radiology Daniel J. Durand, MDa, Anand K. Narayan, MD, PhDb, Frank J. Rybicki, MD, PhDc, Judy Burleson, MHSAd, Paul Nagy, PhDb, Geraldine McGinty, MD, MBAe, Richard Duszak Jr, MD f Abstract The US health care system is in the midst of disruptive changes intended to expand access, improve outcomes, and lower costs. As part of this movement, a growing number of stakeholders have advocated dramatically increasing consumer transparency into the quality and price of health care services. The authors review the general movement toward American health care value transparency within the public, private, and nonprofit sectors, with an emphasis on those initiatives most relevant to radiology. They conclude that radiology, along with other “ancillary services,” has been a major focus of early efforts to enhance consumer price transparency. By contrast, radiology as a field remains in the “middle of the pack” with regard to quality transparency. There is thus the danger that radiology value transparency in its current form will stimulate primarily price- based competition, erode provider profit margins, and

- 2. disincentivize quality. The authors conclude with suggested actions radiologists can take to ensure that a more optimal balance is struck between quality transparency and price transparency, one that will enable true value-based competition among radiologists rather than commoditization. Key Words: Quality, value, transparency, pay for performance, value-based contracting J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12:51-58. Copyright � 2015 American College of Radiology Although there are many reasons the UShealth care systemfails to deliver value on par with those of peer nations, few would argue that “market failure”—the inefficient allocation of goods and services by the free market—plays a significant role. Beginning in March 2013 with Steven Brill’s [1] landmark Time cover story, “Bitter Pill: Why Medical Bills Are Killing Us,” and culminating later that spring with the first ever release by CMS of Medicare pricing data on all US hospitals [2], this view has been empirically validated by reports of price variation aEvolent Health, Arlington, Virginia. bThe Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Sci- ence, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. cApplied Imaging Science Laboratory, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. dDepartment of Quality and Safety, American College of Radiology, Reston, Virginia. eWeill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University, New York, New York.

- 3. fDepartment of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Corresponding author and reprints: Daniel J. Durand, MD, Evolent Health, 800 N Glebe Road, Arlington, VA 22203; e-mail: [email protected] gmail.com. ª 2015 American College of Radiology 1546-1440/14/$36.00 n http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2014.08.015 among hospitals at the local and national levels that appear unrelated to any substantive difference in the quality of care delivered. Within the market for medical imaging services, for example, 500% variations in price in the same metropolitan area have been cited as “commonplace” [3]. Given the broader societal movement toward information transparency in health care, this recent wave of controversy over price variation marks only the beginning of what is likely to be a prolonged national dialogue. We review recent trends toward health care transparency on both quality and price, both from a general perspective and with an eye toward radiology in particular. Our purpose is to acquaint the reader with the major transparency initiatives currently active in the United States throughout the public, private, and nonprofit sectors and to review their potential impact on radiology. THE PREVAILING THEORY: BRINGING PERFECT VALUE TRANSPARENCY TO HEALTH CARE CAN SAVE A FAILING MARKETPLACE Before considering the nature of market failure in the complex ecosystem of US health care, first consider how price and quality are supposed to interact in an “ideal” 51

- 4. mailto:[email protected] mailto:[email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2014.08.015 marketplace in which value is maximized. In this world, value is defined in the simplest terms: some quantity of “quality” per unit price. Rational buyers who desire goods and services and who have access to perfect information on price and quality collectively form a market. Most readers are familiar with the classic price-setting relationship be- tween supply and demand. In most industries, price is also related to quality in that, generally speaking, higher quality goods command higher prices at any time point [4]. When quality is measured in the proper units, this relationship may be positively and perhaps even linearly correlated with price. Some authors have even referred to a “quality elasticity function” that describes the degree to which value-conscious consumers will pay more for progressively higher quality goods (ie, the slope of a regression line that relates price to quality) [5]. For example, a good with a price elasticity of zero is a “perfect” commodity; quality is meaningless, and price is purely a function of quantity supplied and quantity demanded. Such relationships among supply, demand, price, and quality are not necessarily desirable when allocating essential services such as health care. The predictable result would be wide disparities in access and health outcomes based on income levels. This concern over access to high-quality care is the reason many governments, including that of the United States, have taken a heavy hand in regulating health care relative to other sectors of the economy. These regu- lations complicate the price-quality relationship consider- ably. For example, in many states, certificate-of-need

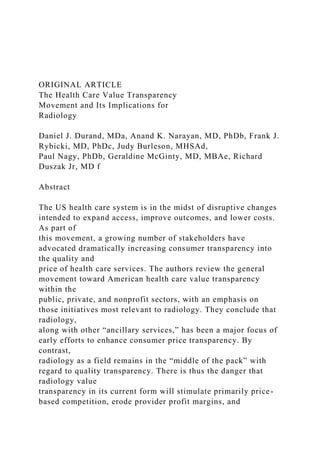

- 5. programs limit the supply of imaging providers, partly as a means of reducing overall health care expenditure, which increases the bargaining power of providers in general and would be expected to increase unit prices across the board for both high- and low-quality imaging services. At the same time, econometric studies of Medicare populations have generally found that quality per unit price (ie, increased price elasticity of quality) is increased in more competitive markets, which has been interpreted as meaning that when providers cannot compete on price, they will compete more aggressively on quality [6]. The preceding two examples are not meant to be exhaustive but merely to illustrate the myriad ways in which both state and federal regulatory bodies can complicate the economic framework described above. Furthermore, empirical research has repeatedly demon- strated that even in relatively unregulated and transparent markets, price-quality relationships are not necessarily linear and often do not conform well to trend lines [7]. Never- theless, the scenarios depicted in Figure 1 are intended to illustrate, at a high level, the theoretical implications of different types of potential consumer behavior in reaction to value transparency and their resultant implications for 52 market dynamics. For inasmuch as consumers (or their proxies, such as a primary care practitioners or insurance benefit managers) are increasingly motivated decision makers who understand and have access to information on both price and quality, this basic framework should apply. A growing chorus of economists, entrepreneurs, and policymakers believe that part of the answer to improving value in US health care is to drastically increase transparency on both price and quality [8]. This, in combination with higher deductibles and other mechanisms of increasing pa-

- 6. tient cost consciousness, should gradually correct irrational variations in price known to plague the system. This is also the approach currently embraced by a large number of health insurers and radiology benefits management organi- zations with regard to imaging utilization management and unit price reduction. By using claims-based analytic algo- rithms, pricing firms can now compare prices with local benchmarks to direct patients to specific sites of care using either carrots (eg, incentivizing patients to choose higher value providers) or sticks (eg, keeping high-priced and/or low-value providers out of the network or using tools such as varied copayments) [9]. Assuming that both measures of price and quality are given ample weight by decision makers, one can immedi- ately see the benefits of such a strategy (Figs. 1A and 1B). The winners include high-quality providers, who can now more reliably charge higher prices. Low-quality providers, who now fetch lower prices for their work, are the losers. Patients as a population receive more consistent value. But the aggregate cost of the services obtained and the average unit price will depend on the dynamics of the market, which are impossible to predict in advance. PRICE AND QUALITY DATA MAY INFLUENCE PATIENT BEHAVIOR IN A DIFFERENTIAL MANNER, LEADING TO SEVERAL POTENTIAL MARKET OUTCOMES One potentially important predictor of market behavior is the relative importance consumers assign to price data versus quality data, which itself depends on the nature of the data provided. Before discussing this in depth, it is important to note that the issue of relative importance or “weighting” is not solely a function of the sheer volume of data available to consumers. Rather, consumers’ decision making will likely be influenced by several factors, including their levels of access to transparency data, ability to understand it, trust in

- 7. its accuracy, and belief that the data are relevant to their own choices of health care providers. For example, if quality data are readily available but poorly understood or not trusted, they will likely not be valued by consumers. Conversely, relatively few data points on quality could be quite powerful Journal of the American College of Radiology Volume 12 n Number 1 n January 2015 Fig 1. Hypothetical graphs showing the relationships between price and quality that could result from different types of consumer behavior. (A) The baseline scenario assumes an essentially random association between quality and price that effectively depicts a dysfunctional market. (B) In this scenario, patients make relatively balanced use of price and quality data, yielding a positive linear relationship between quality and price. (C) In this scenario, patients assign more weight to price than quality, resulting in a relatively “flat” line with overall lower mean prices as unit price reductions become the principal means of competition. (D) In this scenario, radiology services emerge as a “Veblen good,” leading to a general increase in prices. if they are readily accessible, well understood, and relevant, and if they come from a reliable source. The same can be said for measures of price, although with price, the issues of understanding and relevance are unlikely to be limiting factors, because patients generally know what a dollar is and what it is worth to them. If consumers pay more attention to price than to quality, providers will be forced to compete primarily on price to

- 8. attract patients. Assuming supply remains constant and provider cost structures do not change, this will result in a reduction in unit prices (ie, “a race to the bottom”), eroding provider profit margins. In this scenario (Fig. 1C), both patients and payers win value in the short term. As a group, providers lose, although there may be pockets of success among exceptionally high-quality providers or those who are able to achieve especially lean cost structures. In the most extreme version of this scenario, patients make no use whatsoever of quality data, and decisions are made purely on Journal of the American College of Radiology Durand, Narayan, Rybicki n Health Care Value Transparency and R the basis of price as radiologic services are treated as pure commodities. In the very short term, the biggest winner in this scenario is payers, who will accrue most of the value lost by radiologists. Patients with high deductibles and/or high copayments would also net short-term gains in terms of cost avoidance. Assuming healthy competition among payers, this should translate into intermediate-term premium re- ductions, which would transfer some of the value to em- ployers or individuals purchasing insurance (eg, on the federal exchanges). In the long term, however, patients and payers would both lose to the extent that increasingly lower quality imaging would likely adversely affect both health outcomes and the efficiency of medical care delivery. There is an alternative scenario in which transparency could actually boost average prices—one in which providers could capture more value than payers. For some goods and services for which demand is positively correlated with price, high prices increase demand because of the perception by 53 adiology

- 9. some consumers that higher prices mean higher quality. These are properly referred to as Veblen goods (though they are often mischaracterized in the press as “Giffen” goods) [10]. Some economists have suggested that a subset of health care services could behave this way. In Figure 1D, we show a scenario of generally increased unit price—with subsequent boosts to provider profit margins—that could occur in situations in which high-priced providers are paradoxically in higher demand on the basis of patient or consumer perception. However, as we discuss later, such a scenario seems unlikely for imaging. CONSUMER TRANSPARENCY INTO RADIOLOGY PRICES IS WELL DEVELOPED RELATIVE TO OTHER SPECIALTIES AND CONTINUES TO GROW RAPIDLY A tide of health care price transparency initiatives has rolled across the nation over the past decade, driven in part by federal and state legislation [11]. At the time of this writing, some 31 states, “red” and “blue” states alike, have enacted legislation specifically related to the public disclosure of health care pricing [12]. These laws use fairly diverse mechanisms to promote the dissemination of such data. New Hampshire’s HealthCost website represents one of the oldest and most well-documented initiatives. Beginning in 2003, all insurance carriers operating in New Hampshire were required to disclose claims information to the state. Over time, these data were used to develop the New Hampshire Comprehensive Health Information System. Since 2007, the bundled cost of 30 common outpatient health care services (primarily imaging and surgery), along with childbirth as the lone inpatient procedure, have all been posted online. Interestingly, a 2009 analysis by the Center for Health System Change reported that the New Hampshire program had failed to produce any significant changes in price variation, with the authors citing a lack of

- 10. competition among providers and low penetration (<5%) of high-deductible insurance plans among the state popu- lation as two potential reasons for the lack of impact [13]. At the federal level, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act contained two specific provisions that can be ex- pected to increase price transparency. The first began last year with the public disclosure of hospital pricing data, alluded to previously. The second is that, beginning in 2014, health plans listed on the federal exchanges are required to disclose a wealth of information related to premium pricing and benefit structure in plain English to their members. In addition, they must also provide their members with estimated of out-of- pocket costs for certain procedures [14]. Although far less widely cited in the academic literature than these legislative initiatives [15], there is also a great deal 54 of private sector activity focused on providing health care value transparency. Although the subcomponents of com- plex medical care are notoriously difficult to price, discrete services such as laboratory tests and imaging are more easily handled by claims extraction algorithms [16], particularly when performed at freestanding outpatient sites of service. Accordingly, “outpatient ancillaries” have been a major focus of early work to define, understand, and ultimately sell such cost variation data to health care consumers and em- ployers. Although there is a great deal of methodologic variation in deriving such pricing data, the key point is that consumers can compare prices among providers with increasing ease, whereas it remains far more difficult for them to compare quality. Table 1 shows salient examples of the value and price transparency tools currently operating in the US health care system. Companies such as Truven Health Analytics and Cast-

- 11. light Health are marketing this kind of pricing data to large employers and health plans on a national basis. Health in- surers have long had insights into pricing data but have typically been unable to share them because of specific clauses in their provider contracts. In the new model, an employer or health plan contracts with a price transparency firm, allowing its members and employees access to a health care consumer website that facilitates comparison shopping among providers. Typically, these large employers are also transitioning their employees to “consumer-directed” health benefits (ie, lower cost options with higher copayments and higher deductibles to curb excessive utilization). From all appearances, the private sector believes firmly that this model is the wave of the future: when Castlight Health went public, the company was valued at more than 100 times its annual revenue, making it the most optimistically priced initial public offering in the American stock market in the 21st century. Although it is true that firms like Castlight usually also measure quality in some fashion (see the next section), it is equally true that these firms have placed a heavy emphasis on price variation in their public communications (eg, white papers, press releases, marketing materials). For example, Castlight Health’s website boasts an interactive imaging price transparency map that shows regional price variations for imaging services such as head CT, brain MRI, and lumbar spine MRI [17]. There is, unfortunately, no inter- active map for quality variation. The case studies posted online by Castlight tell a similar story. For example, Castlight’s publically disclosed case example of its work with the firm Honeywell details the role of price transparency in its strategy, stating that Castlight highlighted the importance of consumer choice uti-

- 12. lizing maps, pricing data, and ratings to illustrate Journal of the American College of Radiology Volume 12 n Number 1 n January 2015 Table 1. Prominent examples of tools and services offered by companies in the medical imaging price and value transparency marketplace Approach Description Major Examples Value-based steerage Patients are directly engaged to encourage them to use the lowest priced option with comparable “quality” Most major RBM organizations Proprietary consumer price or value transparency portals Online tools that match patients with high-value local imaging providers, with pricing often informed by claims analysis based on commercial or CMS populations Major payers (eg, BCBS, Aetna, Cigna, UnitedHealthcare, WellPoint) Castlight Health Change Healthcare Corporation Truven Healthcare Analytics, Inc ClearCost Health HealthSparq, Inc

- 13. Open-source consumer price transparency portals Browseable databases of local price ranges for common health care procedures, including imaging Health Care Blue Book fairhealthconsumer.org Value-oriented patient referral networks Primary care physicians engaged in risk sharing arrangements (e.g., ACOs) send patients to the highest quality and/or lowest cost provider to optimize population health outcomes and minimize total medical expense Medicare shared savings programs “Pioneer” Medicare ACOs Commercial ACOs sponsored by major payers Provider-owned health plans Note: ACO ¼ accountable care organization; BCBS ¼ BlueCross BlueShield; RBM ¼ radiology benefits management. trade-offs in cost and quality. The two educational themes that were reinforced consistently through the use of maps in the engagement communications were: “Price variance exists, even within network” and “More expensive care is not always better care.” [18] They did not mention which quality metrics were used to discern between providers.

- 14. IMAGING QUALITY TRANSPARENCY REMAINS RELATIVELY UNDERDEVELOPED Although few would argue that there is variation in the level of quality delivered by different radiologists or different radi- ology groups, it is exceedingly difficult to measure, quantify, and distribute information regarding this variation in a way that would be meaningful to consumers or even referring physicians. Nevertheless, there is increasing interest in quality measures throughout medicine, on the basis of the growing societal capability to mandate and implement automated quality data collection across patient populations [19]. Beginning with attempts to define and measure outcomes related to myocardial infarctions, numerous public agencies and professional societies have expanded the scope of their measurement efforts [20]. Many of these metrics have sub- sequently undergone review by the National Quality Forum (NQF), a publicly funded nonprofit organization [21]. For example, in the past 6 years, the NQF has reviewed two rounds of imaging efficiency metrics, several of which were developed by CMS and ultimately incorporated into the CMS Hospital Outpatient Quality Reporting program [22]. Journal of the American College of Radiology Durand, Narayan, Rybicki n Health Care Value Transparency and R Until recently, imaging quality metrics were perilously underdeveloped relative to other specialties and were designed and controlled largely by specialties outside radi- ology. Consider that, at the moment, the ACR is the official steward of just 1 NQF-endorsed metric (participation in the ACR Dose Index Registry�), although it is soon to assume stewardship of 4 additional NQF-endorsed metrics previ- ously developed in conjunction with the Physician Con- sortium for Performance Improvement of the AMA. Furthermore, only 20 of 955 NQF-approved measures (2.1%) explicitly deal with medical imaging [23], despite the fact that imaging accounts for approximately 14% of health

- 15. care costs [24]. Finally, virtually all NQF-approved imaging metrics deal with appropriateness (often more reflective of ordering provider behavior rather than the quality of radiologic service), and none at present focus on patient- based outcomes. At the same time, it is important to note that although NQF endorsement is currently the de facto “gold standard” for quality metric validation, organizations such as CMS increasingly make use of measures that are not yet NQF approved. For this reason, the statistical snapshot presented earlier represents a dated picture that fails to capture late- breaking progress within the radiology community with regard to quality metrics that, although fully developed and with potential impact, have not yet garnered NQF approval. For example, the Qualified Clinical Data Registries (QCDRs) referenced in the recent fiscal cliff legislation may make use of non-NQF-approved metrics. Furthermore, the ACR has applied to serve as a QCDR, offering to report 55 adiology publicly on 20 measures across 5 of the existing ACR data registries. The proposed ACR QDCR metrics focus mainly on radiation dose optimization, mammographic quality measures, turnaround time, and contrast extravasation. If the ACR’s QCDR application is successful, it will represent a significant victory within the radiology quality commu- nity, which will signal that radiology as a field is moving to the forefront of the quality movement. For the moment, however, we remain at the trailing end of the movement along with most other specialties. It is also important to note that several of the afore-

- 16. mentioned NQF-approved imaging-related metrics are part of the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), a CMS program designed to encourage the public reporting of data [25]. Data reported through PQRS will be used to deter- mine the value-based payment modifier, along with cost or “resource use” measures, which will augment Medicare payment for high-value performers and penalize low-value performers. “Performance” in PQRS will be defined by a complex value metric that CMS has yet to explicitly define but will certainly have an aggregated quality measure in the numerator and an aggregated cost measure in the denomi- nator. However, it is important to recognize that only a small percentage of PQRS metrics relate to imaging, and it is possible for large provider groups (eg, large multispecialty groups, integrated delivery networks) to participate in PQRS without reporting any imaging-related metrics at all. Thus, there is a concern that for larger groups within the PQRS program, radiology quality metrics will be largely irrelevant, as they will be lumped together with many other non- radiology metrics—indeed, many large groups and inte- grated delivery networks have already chosen not to report imaging-related metrics at all. Furthermore, even PQRS data collected from “pure” radiology groups are not yet publicly reported in a fashion that consumers can easily access and understand. Thus, PQRS data cannot currently be used by patients to seek out high-quality radiologists. Finally, many of the private sector firms mentioned in Table 1 use their own independent metrics to assess quality. Unfortunately, these metrics themselves tend to be hetero- geneous and sometimes are not well defined or are even intentionally undefined. Such metrics introduce the risk for radiology value measures’ becoming proprietary and completely ambiguous. In summary, despite recent progress, radiology as a field

- 17. remains in the “middle of the pack” with regard to quality metric development and significantly trails specialties at the leading edge of the quality movement, such as cardiology, primary care, orthopedics, and oncology. Radiology quality metrics themselves can be loosely divided into 3 groups: measures of imaging appropriateness, measures of radia- tion safety, and measures of radiologist performance (eg, 56 turnaround time, diagnostic accuracy) and their subsequent impact on patient outcomes [26]. The current strategy of organized radiology is to begin to meet the need for quality transparency by focusing mainly on evidence-based stan- dards for imaging appropriateness and supporting greater uptake through the use of clinical decision support and order entry systems. Although the next generation of im- aging metrics will likely be more process and performance oriented, radiology quality metrics will probably always be inherently less directly linked to health outcomes than those developed by other specialists (eg, surgeons) who contribute more directly to individual patient care. THE COMBINATION OF RAPIDLY ADVANCING PRICE TRANSPARENCY AND SLOWER MOVING QUALITY TRANSPARENCY HEIGHTENS THE THREAT OF COMMODITIZATION On the basis of the confluence of events we describe, it can be expected that health care value transparency will stimu- late primarily price-based competition between radiology providers, a scenario analogous to Figure 1C. There are several reasons this is thought to be the case. First, because of changes related to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, patients in the United States will have increasingly more “skin in the game” (eg, high de- ductibles) and are likely to be increasingly sensitive to price. Veblen good effects for radiology are unlikely, because

- 18. consumers tend to associate imaging quality with the tech- nology itself rather than the skill or training of the radiol- ogist (provided, of course, they are even aware that a radiologist is a physician) [27]. Second, it has been well documented that patients have little insight into what high-quality imaging services get them in terms of health outcomes [28]. In other words, even if provider-level data on quality are made accessible to the public, US health care consumers need to become educated in and convinced of the value of these data and must also come to trust its source in order for it to meaningfully inform their choices of providers. Unfortunately, this lack of awareness of the value of high-quality radiology is not limited to patients but is a common misconception among our fellow physicians as well as health care policymakers. In 2012, a broad coalition of respected health care economists and policy experts led by Ezekiel Emanuel openly referred to radiology as a commodity in the pages of the New England Journal of Medicine, writing that “Medicare should extend competitive bidding to medical devices, laboratory tests, radiologic diagnostic services, and all other commodities” [29]. Interestingly, the same author group wholeheartedly endorsed “requiring full transparency of [health care] prices” as part of its recommendations. Journal of the American College of Radiology Volume 12 n Number 1 n January 2015 RECOMMENDATIONS: ACTIONABLE STEPS TO MOVE FROM SIMPLE PRICE TRANSPARENCY TO TRUE VALUE TRANSPARENCY It is precisely because radiologists are physicians first and business people second that this scenario is distasteful. Having spent years acquiring our skills and taken oaths to

- 19. provide the highest quality care possible to each patient, it is demoralizing to consider that market forces may push us toward commoditization and the delivery of lower quality care. Fortunately, health care value transparency remains in its infancy, and the markets alluded to above are probably nowhere near equilibrium. Corrective courses of action remain available. It is our opinion that radiologists should not attempt to fight the inevitable tide of price transparency. Once started, such processes are unlikely to be reversed in a free society. The tactics of consolidation and tacit collaboration among groups to prevent price-based competition are likewise un- attractive; they fail to leverage the opportunity that true value transparency presents to patients, society at large, and radiology as a field. Instead, radiologists should embrace quality transparency and seek “mastery of the numerator” in the value equation. We can avoid commoditization by coming to consensus on what quality means, communicating our shared vision to the public, and actively engaging in healthy value-based compe- tition among ourselves, rather than viewing quality reporting as a mere compliance issue handed down from above. Ini- tiatives such as the ACR’s Imaging 3.0� [30], for example, provide a compelling platform for codeveloping a universal quality framework that can help structure this dialogue going forward. Therefore, we recommend the following set of ac- tions to ensure that health care transparency truly rewards high-value radiologic services: 1. Invest broadly in quality research and work toward endorsing specific metrics that facilitate meaningful quality comparisons among providers. This means accepting the reality that performance is not equal among radiologists.

- 20. 2. Actively support professional societies (eg, the ACR) in their ongoing efforts to provide systematic oversight of quality metrics used by payers, radiology benefits man- agement organizations, and other value transparency firms—recall that the less this is about quality competi- tion and the more it is about price competition, the more value other market players (eg, payers) will grab from radiologists. 3. Radiologists should actively participate in quality metrics and registries. The registries maintained by the ACR will continue to grow, and broad participation will help ensure that the assessment of radiologists remains in Journal of the American College of Radiology Durand, Narayan, Rybicki n Health Care Value Transparency and R control of radiologists. In addition, the establishment of large databases will foster the transition toward more accuracy- and performance-based metrics that are more reflective of radiologists’ skills. Eventually, the ACR registries may also offer a convenient means of direct public reporting through CMS programs such as QCDR. 4. Radiology professional societies must invest in research to demonstrate the high downstream costs (eg, total medical expense) and/or poor outcomes associated with low- quality imaging (eg, progression of undetected disease, excessive follow-up imaging, unneeded surgery or bi- opsies, unnecessary radiation exposure) and encourage the publication of papers outside our own literature in high-impact journals read by other specialists and poli- cymakers (eg, Health Affairs, the New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA). a TAKE-HOME POINTS

- 21. n Patients do not currently have access to data that would allow them to choose one radiology provider over another on the basis of quality, a point that is generally true for all medical specialties apart from those that spearheaded the quality movement over the past two decades (eg, cardiology, primary care, orthopedics). n Radiology has been thrust to the forefront of the price transparency movement, as both patients and refer- ring physicians are increasingly being given radiology pricing data by a variety of public, private, and nonprofit entities and are further being encouraged to “price-shop” for imaging services. n On this basis, health care value transparency in its current form will stimulate primarily price-based competition among radiology providers, a scenario that heightens the threat of commoditization. n Potential actions to combat commoditization include establishing unified systems for defining, measuring, and reporting data on imaging quality as well as promoting and supporting research relating higher imaging quality to improved population health out- comes and/or lower total medical expenses. REFERENCES 1. Brill S. Bitter pill: why medical bills are killing us. Time. Available at: http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2136864,0 0. html. Accessed February 18, 2014. 2. Tocknell MD. CMS releases hospital pricing data. Available at: http://

- 22. www.healthleadersmedia.com/content/hep-292001/CMS- Releases- Hospital-Pricing-Data. Accessed February 18, 2014. 3. Kliff S. How much does an MRI cost? In D.C., anywhere from $400 to $1,861. The Washington Post. Available at: http://www. 57 diology http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2136864,0 0.html http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2136864,0 0.html http://www.healthleadersmedia.com/content/hep-292001/CMS- Releases-Hospital-Pricing-Data http://www.healthleadersmedia.com/content/hep-292001/CMS- Releases-Hospital-Pricing-Data http://www.healthleadersmedia.com/content/hep-292001/CMS- Releases-Hospital-Pricing-Data http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/03/13 /how-much-does-an-mri-cost-in-d-c-anywhere-from-400-to- 1861/ washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/03/13/how-much- does- an-mri-cost-in-d-c-anywhere-from-400-to-1861/. Accessed February 18, 2014. 4. Leibenstein H. Bandwagon, snob, and Veblen effects in the theory of consumers’ demand. Q J Econ 1950;64:183-207. 5. Narasimhan C, Sen S. Measuring quality perceptions.

- 23. Marketing Lett 1992;3:147-56. 6. Gaynor M. What do we know about competition and quality in health care markets? No. w12301. Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bu- reau of Economic Research; 2006. 7. Shugan S. The price-quality relationship. Adv Consumer Res 1984;11: 627-32. 8. Cutler D, Dafny L. Designing transparency systems for medical care prices. N Engl J Med 2011;364:894-5. 9. Levin D, Rao V, Berlin J. Ensuring the Future of Radiology: How to Respond to the Threats. J Am Coll Radiol 2013;10: 647-51. 10. Chao A, Schor J. Empirical tests of status consumption: evidence from women’s cosmetics. J Econ Psychol 1998;19:107-31. 11. Sinaiko A, Rosenthal M. Increased price transparency in health care— challenges and potential effects. N Engl J Med 2011;364:891-4. 12. National Conference of State Legislatures. Transparency and disclosure of health costs and provider payments: state actions. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/transparency-and- disclosure-health- costs.aspx. Accessed February 18, 2014.

- 24. 13. Tu H, Lauer J. Impact of health care price transparency on price variation: the New Hampshire experience. Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change 2009;128:1-4. 14. The Commonwealth Fund. Health care price transparency: can it promote high-value care? Available at: http://www.commonwealth fund.org/Newsletters/Quality-Matters/2012/April-May/In- Focus.aspx. Accessed February 18, 2014. 15. Philips K, Labno A. A trend: private companies provide health care price data. Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/01/08/a- trend-private-companies-provide-health-care-price-data/. Accessed February 18, 2014. 16. Bossuyt X, Verweire K, Blanckaert N. Laboratory medicine: challenges and opportunities. Clin Chem 2007;53:1730-3. 58 17. Castlight Health. New analysis details most and least expensive cities for common medical services. Available at: http://www.castlighthealth. com/price-variation-map/. Accessed August 3, 2014. 18. Castlight Health. Introducing employee accountability with health care transparency. Available at: http://www.castlighthealth.com/pdf/

- 25. Castlight-Honeywell-Case-Study.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2014. 19. Loeb J. The current state of performance measurement in health care. Int J Qual Health Care 2004;16(suppl):5-9. 20. Berenson RA, Pronovost PJ, Krumholz HM. Achieving the potential of health care performance measures. Available at: http://www.rwjf. org/en/research-publications/find-rwjf- research/2013/05/achieving-the- potential-of-health-care-performance-measures.html. Accessed February 18, 2014. 21. Kizer K. The National Quality Forum enters the game. Int J Qual Health Care 2000;12:85-7. 22. Anumula N, Sanelli P. Hospital outpatient quality data reporting program. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:225-6. 23. American College of Radiology. PQRS measures relevant to radiology. Available at: http://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/Quality- Measurement/ PQRS/Measures. Accessed February 18, 2014. 24. Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti D, Larson E. Rising use of diagnostic medical imaging in a large integrated health system. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:1491-502. 25. National Quality Forum. National voluntary consensus

- 26. standards for outpatient imaging efficiency: a consensus report. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2009/08/National_Vo luntary_ Consensus_Standards_for_Outpatient_Imaging_Efficiency__A_ Consensus_ Report.aspx. Accessed February 18, 2014. 26. Shyu JY, Burleson J, Tallant C, Seidenwurm DJ, Rybicki FJ. Perfor- mance measures in radiology. J Am Coll Radiol 2014;11:456- 63. 27. Usman O. We need more supply-side regulation. Health Aff (Mill- wood) 2011;30:1615. 28. Miller P, Gunderman R, Lightburn J, Miller D. Enhancing patients’ experiences in radiology: through patient-radiologist interaction. Acad Radiol 2013;20:778-81. 29. Emanuel E, Tanden N, Altman S, et al. A systemic approach to containing health care spending. N Engl J Med 2012;367:949- 54. 30. Ellenbogen P. Imaging 3.0: what is it? J Am Coll Radiol 2013;10:229. Journal of the American College of Radiology Volume 12 n Number 1 n January 2015 http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/03/13 /how-much-does-an-mri-cost-in-d-c-anywhere-from-400-to-

- 29. cy__A_Consensus_Report.aspx http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2009/08/National_Vo luntary_Consensus_Standards_for_Outpatient_Imaging_Efficien cy__A_Consensus_Report.aspx http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1546-1440(14)00493-1/sref15 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1546-1440(14)00493-1/sref15 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1546-1440(14)00493-1/sref16 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1546-1440(14)00493-1/sref16 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1546-1440(14)00493-1/sref17 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1546-1440(14)00493-1/sref17 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1546-1440(14)00493-1/sref17 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1546-1440(14)00493-1/sref18 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1546-1440(14)00493-1/sref18 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1546-1440(14)00493-1/sref19The Health Care Value Transparency Movement and Its Implications for RadiologyThe Prevailing Theory: Bringing Perfect Value Transparency to Health Care Can Save a Failing MarketplacePrice and Quality Data May Influence Patient Behavior in a Differential Manner, Leading to Several Potential Market OutcomesConsumer Transparency Into Radiology Prices Is Well Developed Relative to Other Specialties and Continues to Grow RapidlyImaging Quality Transparency Remains Relatively UnderdevelopedThe Combination of Rapidly Advancing Price Transparency and Slower Moving Quality Transparency Heightens the Threat of Comm ...Recommendations: Actionable Steps to Move From Simple Price Transparency to True Value TransparencyTake-Home PointsReferences