802CHAPTER 25UNDERSTANDING DRAMAThe distinctive ap.docx

- 1. 802 CHAPTER 25 UNDERSTANDING DRAMA The distinctive appearance of a script, with its divisions into acts and scenes, identi�es drama as a unique form of literature. A play is written to be per- formed in front of an audience by actors who take on the roles of the charac- ters and who present the story through dialogue and action. (An exception is a closet drama, which is meant to be read, not performed.) In fact, the term theater comes from the Greek word theasthai, which means “to view” or “to see.” Thus, drama is different from novels and short stories, which are meant to be read. The Ancient Greek Theater The dramatic presentations of ancient Greece developed out of religious rites performed to honor gods or to mark the coming of spring. Play- wrights such as Aeschylus (525–456 b.c.), Sophocles (496–406 b.c.), and Euripides (480?–406 b.c.) wrote plays to be performed and judged at com-

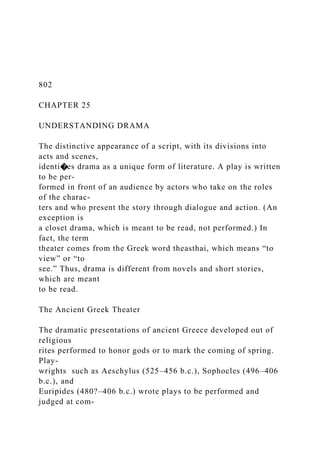

- 2. petitions held during the yearly Dionysian festivals. Works were chosen by a selection board and evaluated by a panel of judges. To compete in the contest, writers had to submit three tragedies, which could be either based on a common theme or unrelated, and one comedy. Unfortunately, very few of these ancient Greek plays survive today. The open-air, semicircular ancient Greek theater, built into the side of a hill, looked much like a primitive version of a modern sports stadium. Some Greek theaters, such as the Athenian theater, could seat almost seventeen thousand spectators. Sitting in tiered seats, the audience would look down on the orchestra, or “dancing place,” occupied by the chorus— originally a group of men (led by an individual called the choragos) who danced and chanted and later a group of onlookers who commented on the drama. Dramatic Literature Origins of Modern Drama 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O

- 3. N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S Origins of Modern Drama 803 Raised a few steps above the orchestra was a platform on which the actors performed. Behind this platform was a skene, or building, that origi- nally served as a resting place or dressing room. (The modern word scene is derived from the Greek skene.) Behind the skene was a line of pillars called a colonnade, which was covered by a roof. Actors used the skene for

- 4. entrances and exits; beginning with the plays of Sophocles, painted back- drops were hung there. These backdrops, however, were most likely more decorative than realistic. Historians believe that realistic props and scenery were probably absent from the ancient Greek theater. Instead, the setting was suggested by the play’s dialogue, and the audience had to imagine the physical details of a scene. Two mechanical devices were used. One, a rolling cart or platform, was sometimes employed to introduce action that had occurred offstage. For example, actors frozen in position could be rolled onto the roof of the skene to illustrate an event such as the killing of Oedipus’s father, which occurred before the play began. Another mechanical device, a small crane, was used to show gods ascending to or descending from heaven. Such devices enabled playwrights to dramatize the myths that were celebrated at the Dionysian festivals. The ancient Greek theater was designed to enhance acoustics. The �at stone wall of the skene re�ected the sound from the orchestra and the stage, and the curved shape of the amphitheater captured the sound, Grand Theater at Ephesus (3rd century B.C.), a Greek

- 5. settlement in what is now Turkey Da v e G . Ho u s e r/Do c u m e n ta ry Va l u e /Co rb i s 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S 804 Chapter 25 • Understanding Drama

- 6. enabling the audience to hear the lines spoken by the actors. Each actor wore a stylized mask, or persona, to convey to the audience the personal- ity traits of the particular character being portrayed—a king, a soldier, a wise old man, a young girl (female roles were played by men). The mouths of these masks were probably constructed so they ampli�ed the voice and projected it into the audience. In addition, the actors wore kothorni, high shoes that elevated them above the stage, perhaps also helping to project their voices. Due to the excellent acoustics, audiences who see plays per- formed in these ancient theaters today can hear clearly without the aid of microphones or speaker systems. Because actors wore masks and because males played the parts of women and gods as well as men, acting methods in the ancient Greek theater were probably not realistic. In their masks, high shoes, and full- length tunics (called chiton), actors could not hope to appear natural or to mimic the atti- tudes of everyday life. Instead, they probably recited their lines while stand- ing in stylized poses, with emotions conveyed more by gesture and tone than by action. Typically, three actors had all the speaking roles. One actor—the protagonist—would play the central role and have the largest speaking part.

- 7. Two other actors would divide the remaining lines between them. Although other characters would come on and off the stage, they would usually not have speaking roles. Ancient Greek tragedies were typically divided into �ve parts. The �rst part was the prologos, or prologue, in which an actor gave the background or explanations that the audience needed to follow the rest of the drama. Then came the párodos, in which the chorus entered and commented on the events presented in the prologue. Following this were several episo- dia, or episodes, in which characters spoke to one another on the stage and developed the central con ict of the play. Alternating with episodes were stasimon (choral odes), in which the chorus commented on the exchanges that had taken place during the preceding episode. Frequently, the choral odes were divided into strophes, or stanzas, which were recited or sung as the chorus moved across the orchestra in one direction, and antistrophes, which were recited as it moved in the opposite direction. (Interestingly, the chorus stood between the audience and the actors, often functioning as an additional audience, expressing the political, social, and moral views of the community.) The �fth part was the exodos, the last scene of the play, during

- 8. which the con ict was resolved and the actors left the stage. Using music, dance, and verse—as well as a variety of architectural and technical innovations—the ancient Greek theater was able to convey the traditional themes of tragedy. Thus, the Greek theater powerfully expressed ideas that were central to the religious festivals in which they �rst appeared: the reverence for the cycles of life and death, the unavoidable dictates of the gods, and the inscrutable workings of fate. 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E

- 9. 1 5 0 3 T S Origins of Modern Drama 805 The Elizabethan Theater The Elizabethan theater, in uenced by the classical traditions of Roman and Greek dramatists, traces its roots back to local religious pageants performed at medieval festivals during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Town guilds—organizations of craftsmen who worked in the same profession— reenacted Old and New Testament stories: the fall of man, Noah and the ood, David and Goliath, and the cruci�xion of Christ, for example. Church fathers encouraged these plays because they brought the Bible to a largely illiterate audience. Sometimes these spectacles, called mystery plays, were presented in the market square or on the church steps, and at other times actors appeared on movable stages or wagons called pageants, which could be wheeled to a given location. (Some of these wagons were

- 10. quite elaborate, with trapdoors and pulleys and an upper tier that simulated heaven.) As mys- tery plays became more popular, they were performed in series over several days, presenting an entire cycle of a holiday—the cruci�xion and resurrec- tion of Christ during Easter, for example. Performance of a mystery play Art Resource 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5

- 11. 0 3 T S 806 Chapter 25 • Understanding Drama Related to mystery plays are morality plays, which developed in the four- teenth and �fteenth centuries. Unlike mystery plays, which depict scenes from the Bible, morality plays allegorize the Christian way of life. Typically, characters representing various virtues and vices struggle or debate over the soul of man. Everyman (1500), the best known of these plays, dramatizes the good and bad qualities of Everyman and shows his struggle to determine what is of value to him as he journeys toward death. By the middle of the sixteenth century, mystery and morality plays had lost ground to a new secular drama. One reason for this decline was that mys- tery and morality plays were associated with Catholicism and consequently discouraged by the Anglican clergy. In addition, newly discovered plays of ancient Greece and Rome introduced a dramatic tradition that supplanted the traditions of religious drama. English plays that followed the classic model were sensational and bombastic, often dealing with

- 12. murder, revenge, and blood retribution. Appealing to privileged classes and commoners alike, these plays were extremely popular. (One source estimates that in London, between 20,000 and 25,000 people attended performances each week.) In spite of the popularity of the theater, actors and playwrights encoun- tered a number of dif�culties. First, they faced opposition from city of�cials who were averse to theatrical presentations because they thought that the crowds attending these performances spread disease. Puritans opposed the theater because they thought plays were immoral and sinful. Finally, some people attached to the royal court opposed the theater because they thought that the playwrights undermined the authority of Queen Elizabeth by spread- ing seditious ideas. As a result, during Elizabeth’s reign, performances were placed under the strict control of the Master of Revels, a public of�cial who had the power to censor plays (and did so with great regularity) and to grant licenses for performances. Acting companies that wanted to put on a performance had to obtain a license—possible only with the patronage of a powerful nobleman—and to perform the play in an area designated by the queen. Despite these

- 13. dif�culties, a number of actors and playwrights gained a measure of �nancial independence by joining together and forming acting companies. These com- panies of professional actors performed works such as Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine and Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy in tavern courtyards and then eventually in permanent theaters. According to scholars, the structures of the Elizabethan theater evolved from these tavern courtyards. William Shakespeare’s plays were performed at the Globe Theatre (a corner of which was unearthed in December 1988). Although scholars do not know the exact design of the original Globe, drawings from the period provide a good idea of its physical features. The major difference between the Globe and today’s theaters is the multiple stages on which action could be performed. The Globe consisted of a large main stage that extended out 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S ,

- 14. M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S Origins of Modern Drama 807 into the open-air yard where the groundlings, or common people, stood. Spectators who paid more sat on small stools in two or three levels of galleries that extended in front of and around the stage. (The theater could probably seat almost two thousand people at a performance.) Most of the play’s action occurred on the stage, which had no curtain and could be seen from three sides. Beneath the stage was a space called the hell, which could be reached when the oorboards were removed. This space enabled actors to

- 15. “disappear” or descend into a hole or grave when the play called for such action. Above the stage was a roof called the heavens, which protected the actors from the weather and contained ropes and pulleys used to lower props or to create special effects. At the rear of the stage was a narrow alcove covered by a curtain that could be open or closed. This curtain, often painted, functioned as a decora- tive rather than a realistic backdrop. The main function of this alcove was to enable actors to hide or disappear when the script called for them to do so. Some Elizabethan theaters contained a rear stage instead of an alcove. Because the rear stage was concealed by a curtain, props could be arranged on it ahead of time. When the action on the rear stage was �nished, the curtain would be closed and the action would continue on the front stage. On either side of the rear stage was a door through which the actors could enter and exit the front stage. Above the rear stage was a curtained stage called the chamber, which functioned as a balcony or as any other setting located above the action taking place on the stage below. On either side of the chamber were casement windows, which actors could use when a play

- 16. called for a conversation with someone leaning out a window or standing on a balcony. Above the chamber was the music gallery, a balcony that housed the musicians who provided musical interludes throughout the play (and that doubled as a stage if the play required it). The huts, windows located above the music gallery, could be used by characters playing lookouts or sen- tries. Because of the many acting sites, more than one action could take place simultaneously. For example, lookouts could stand in the towers of Hamlet’s castle while Hamlet and Horatio walked the walls below. During Shakespeare’s time, the theater had many limitations that chal- lenged the audience’s imagination. First, young boys—usually between the ages of ten and twelve—played all the women’s parts. In addition, there was no arti�cial lighting, so plays had to be performed in daylight. Rain, wind, or clouds could disrupt a performance or ruin an image—such as “the morn in russet mantle clad”—that the audience was asked to imagine. Finally, because few sets and props were used, the audience often had to visualize the high walls of a castle or the trees of a forest. The plays were performed without intermission, except for musical interludes that occurred at various points. Thus, the experience of seeing one of Shakespeare’s plays staged in the

- 17. Elizabethan theater was different from seeing it staged in a modern theater. 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S 808 Chapter 25 • Understanding Drama

- 18. The Globe Playhouse, 1599–1613; a conjectural reconstruction. From C. Walter Hodges The Globe Restored: A Study of the Elizabethan Theatre. New York: Norton, 1973. Source: C .W . Hodges . Conjectural Reconstruction of the Globe Playhouse, 1965 . Pen & ink . 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S

- 19. Origins of Modern Drama 809 Today, a reconstruction of the Globe Theatre (above) stands on the south bank of the Thames River in London. In the 1940s, the American actor Sam Wanamaker visited London and was shocked to �nd nothing that commemorated the site of the original Globe. He eventually decided to try to raise enough money to reconstruct the Globe in its original location. The Globe Playhouse Trust was founded in the 1970s, but the actual con- struction of the new theater did not begin until the 1980s. After a number of setbacks—for example, the Trust ran out of funds after the construction of a large underground “diaphragm” wall needed to keep out the river water—the project was �nally completed. The �rst performance at the reconstructed Globe was given on June 14, 1996, which would have been the late Sam Wanamaker’s 77th birthday. The Modern Theater Unlike the theaters of ancient Greece and Elizabethan England, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century theaters—such as the Palais Royal, where the great French playwright Molière presented many of his plays— were covered by a roof, beautifully decorated, and illuminated

- 20. by candles so that plays could be performed at night. The theater remained brightly lit Aerial view of the reconstructed Globe Theatre in London Source: ©Jason Hawkes/Corbis 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S

- 21. 810 Chapter 25 • Understanding Drama even during performances, partly because there was no easy way to extin- guish hundreds of candles and partly because people went to the theater as much to see each other as to see the play. A curtain opened and closed between acts, and the audience of about five hundred spectators sat in a long room and viewed the play on a picture-frame stage. This type of stage, which resembles the stages on which plays are performed today, contained the action within a prosce- nium arch that surrounded the opening through which the audience viewed the performance. Thus, the action seemed to take place in an adjoining room with one of its walls cut away. Painted scenery (some of it quite elaborate), intricately detailed costumes, and stage makeup were commonplace, and for the �rst time women performed female roles. In addition, a complicated series of ropes, pulleys, and cranks enabled stage- hands to change scenery quickly, and sound-effects machines could give audiences the impression that they were hearing a galloping horse or a rag- ing thunderstorm. Because the theaters were small, audiences were rela-

- 22. tively close to the stage, so actors could use subtle movements and facial expressions to enhance their performances. Many of the �rst innovations in the theater were quite basic. For example, the �rst stage lighting was produced by candles lining the front of the stage. This method of lighting was not only ineffective— actors were lit from below and had to step forward to be fully illuminated—but also dan- gerous. Costumes and even entire theaters could (and did) catch �re. Later, covered lanterns with re ectors provided better and safer lighting. In the nineteenth century, a device that used an oxyhydrogen ame directed on a cylinder of lime created extremely bright illumination that could, with the aid of a lens, be concentrated into a spotlight. (It is from this method of stage lighting that we get the expression to be in the limelight.) Eventually, in the twentieth century, electric lights provided a depend- able and safe way of lighting the stage. Electric spotlights, footlights, and ceiling light bars made the actors clearly visible and enabled playwrights to create special effects. In Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman (p. 960), for example, lighting focuses attention on action in certain areas of the stage while other areas are left in complete darkness.

- 23. Along with electric lighting came other innovations, such as electronic ampli�cation. Microphones made it possible for actors to speak conversation- ally and to avoid using unnaturally loud “stage diction” to project their voices to the rear of the theater. Microphones placed at various points around the stage enabled actors and actresses to interact naturally and to deliver their lines audibly even without facing the audience. More recently, small wireless microphones have eliminated the unwieldy wires and the “dead spaces” left between upright or hanging microphones, allowing characters to move freely around the stage. 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R

- 24. I N E 1 5 0 3 T S Origins of Modern Drama 811 The true revolutions in staging came with the advent of realism in the middle of the nineteenth century. Until this time, scenery had been painted on canvas backdrops that trembled visibly, especially when they were inter- sected by doors through which actors and actresses entered. With realism came settings that were accurate down to the smallest detail. (Improved lighting, which revealed the inadequacies of painted backdrops, made such realistic stage settings necessary.) Backdrops were replaced by the box set, three at panels arranged to form connected walls, with the fourth wall removed to give the audience the illusion of looking into a room. The room itself was decorated with real furniture, plants, and pictures on the walls; the door of one room might connect to another completely furnished

- 25. room, or a window might open to a garden �lled with realistic foliage. In addition, new methods of changing scenery were employed. Elevator stages, hydraulic lifts, and moving platforms enabled directors to make complicated changes in scenery out of the audience’s view. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, however, some playwrights reacted against what they saw as the excesses of realism. They introduced surrealistic stage settings, in which color and scenery mirrored the uncontrolled images of dreams, and expressionistic stage Thrust-Stage Theater. Rendering of the thrust stage at the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis. With seats on three sides of the stage area, the thrust stage and its background can assume many forms. Entrances can be made from the aisles, from the sides, through the stage floor, and from the back. Source: Alvis Upitis/Getty Images 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E

- 26. S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S 812 Chapter 25 • Understanding Drama settings, in which costumes and scenery were exaggerated and distorted to re ect the workings of a troubled, even unbalanced mind. In addition, playwrights used lighting to create areas of light, shadow, and color that reinforced the themes of the play or re ected the emotions of the protago- nist. Eugene O’Neill’s 1920 play The Emperor Jones, for example, used a series of expressionistic scenes to show the deteriorating mental

- 27. state of the terri�ed protagonist. Sets in contemporary plays run the gamut from realistic to fantastic, from a detailed re-creation of a room in a production of Tennessee Wil- liams’s The Glass Menagerie (1945) to dreamlike sets for Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones (1920) and Edward Albee’s The Sandbox (1959). Motor- ized devices, such as revolving turntables, and wagons—scenery mounted on wheels—make possible rapid changes of scenery. The Broadway musical Les Misérables, for example, required scores of elaborate sets— Parisian slums, barricades, walled gardens—to be shifted as the audience watched. A gigan- tic barricade constructed on stage at one point in the play was later rotated to show the carnage that had taken place on both sides of a battle. Light, sound, and smoke were used to heighten the impact of the scene. Today, as dramatists attempt to break down the barriers that separate audiences from the action they are viewing, plays are not limited to the picture-frame stage; in fact, they are performed on many different kinds of stages. Some plays take place on a thrust stage (pictured on the previous page), which has an area that projects out into the audience. Other plays are performed on an arena stage, with the audience surrounding

- 28. the actors. (This kind of performance is often called theater in the round.) In addi- tion, experiments have been done with environmental staging, in which the stage surrounds the audience or several stages are situated at various locations throughout the audience. Plays may also be performed outdoors, in settings ranging from parks to city streets. Some playwrights even try to blur the line that divides the audience from the stage by having actors move through or sit in the audience— or even by eliminating the stage entirely. For example, Tony ’n Tina’s Wedding, a participatory drama created in 1988 by the theater group Arti- �cial Intelligence, takes place not in a theater but at a church where a wedding is performed and then at a catering hall where the wedding recep- tion is held. Throughout the play, the members of the audience function as guests, joining in the wedding celebration and mingling with the actors, who improvise freely. A more recent example of participatory drama is Sleep No More, which takes place in a block of warehouses (which has been transformed into the McKittrick Hotel) in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City. The play is a wordless production of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Audience

- 29. members, who must wear white Venetian carnival masks and remain silent at all times, are 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S Origins of Modern Drama 813

- 30. taken by elevator to various oors of the “hotel.” Once deposited, they are free to follow any of the actors, who appear and disappear at will, or to explore the hotel’s many rooms. The action can be intense, with audience members chas- ing actors down dark, narrow hallways or up and down stairs to other oors of the hotel, and at times, being pulled into the action of the play. Arena-Stage Theater. The arena theater at the Riverside Community Players in Riverside, California. The audience surrounds the stage area, which may or may not be raised. Use of scenery is limited—perhaps to a single piece of scenery standing alone in the middle of the stage. Source: Courtesy The Arena Theatre, Riverside Community Players, Riverside, CA Scene from the participatory drama Sleep No More Credit: Lucas Jackson/Reuters/Corbis 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S ,

- 31. M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S 814 Chapter 25 • Understanding Drama ANTON CHEKHOV (1860–1904) is an important nineteenth- century CHEKHOV (1860–1904) is an important nineteenth- century CHEKHOV Russian playwright and short story writer . He became a doctor and, as a young adult, supported the rest of his family after his father’s bankruptcy . After his early adult years in Moscow, Chekhov spent the rest of his life in the country, moving to Yalta, a resort town in Crimea, for his health (he suffered from tuberculosis) . He continued to write plays, mostly for the Moscow Art Theatre, although he

- 32. could not supervise their production as he would have wished . His plays include The Seagull (1896),The Seagull (1896),The Seagull Uncle Vanya (1898), Uncle Vanya (1898), Uncle Vanya The Three Sisters (1901), and The Three Sisters (1901), and The Three Sisters The Cherry Orchard (1904)The Cherry Orchard (1904)The Cherry Orchard . Today, no single architectural form de�nes the theater. The modern stage is a exible space suited to the many varieties of contemporary theatrical production. Dramatic works differ from other prose works in a number of fairly obvious ways. For one thing, plays look different on the page: generally, they are divided into acts and scenes; they include stage directions that specify char- acters’ entrances and exits and describe what settings look like and how char- acters look and act; and they consist primarily of dialogue, lines spoken by the characters. And, of course, plays are different from other prose works in that they are written not to be read but to be performed in front of an audience. Unlike novels and short stories, plays do not usually have narrators to tell the audience what a character is thinking or what happened in the

- 33. past; for the most part, the audience knows only what characters reveal. To compensate for the absence of a narrator, playwrights can use monologues (extended speeches by one character), soliloquies (monologues in which a character expresses private thoughts while alone on stage), or asides (brief comments by a character who reveals thoughts by speaking directly to the audience without being heard by the other characters). In addition to these dramatic techniques, a play can also use costumes, scenery, props, music, lighting, and other techniques to enhance its impact on the audience. The play that follows, Anton Chekhov’s The Brute (1888), is typical of modern drama in many respects. A one-act play translated from Russian, it is essentially a struggle of wills between two headstrong characters, a man and a woman, with action escalating through the characters’ increasingly heated exchanges of dialogue. Stage directions brie y describe the setting— “the drawing room of a country house”—and announce the appearance of various props. They also describe the major characters’ appearances as well as their actions, gestures, and emotions. Because the play is a farce, it features broad physical comedy, asides, wild dramatic gestures, and elaborate �gures of speech, all designed to enhance its comic effect.

- 34. Defining Drama So ur ce : © Be tt m an n/ Co rb is 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L

- 35. V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S Glaspell: Trifles 867 SUSAN GLASPELL (1882–1948) was born in Davenport, Iowa, and graduated from Drake University in 1899 . First a reporter and then a freelance writer, she lived in Chicago (where she was part of the Chicago renaissance that included poet Carl Sandburg and novelist Theodore Dreiser) and later in Greenwich Village . Her works include two plays in addition to Trifles, The Verge (1921) and The Verge (1921) and The Verge Alison’s House (1930), and several novels, including Fidelity (1915) and Fidelity (1915) and Fidelity The Morning Is Near Us (1939) . With her husband, George The Morning Is Near Us (1939) . With her husband, George The Morning Is Near Us Cram Cook, she founded the Provincetown Players, which became the staging ground for innovative plays by Eugene O’Neill, among others . Glaspell herself wrote plays for the Provincetown Players,

- 36. beginning with Trifles, which she created for the 1916 season although she had never previously written a drama . The play opened on August 8, 1916, with Glaspell and her husband in the cast . Glaspell said she wrote Trifles in one afternoon, sitting in the empty theater and looking at the bare stage: “After a time, the stage became a kitchen—a kitchen there all by itself .” She remembered a murder trial she had covered in Iowa in her days as a reporter, and the story began to play itself out on the stage as she gazed . Throughout her revisions, she said, she returned to look at the stage to see whether the events she was recording came to life on it . Although Glaspell later rewrote Trifles as a short Trifles as a short Trifles story called “A Jury of Her Peers,” the play remains her most successful and memorable work . Cultural Context One of the main themes of this play is the contrast between the sexes in terms of their roles, rights, and responsibilities . In 1916, when Trifles was first produced, Trifles was first produced, Trifles women were not allowed to serve on juries in most states . This circumstance was in accor- dance with other rights denied to women, including the right to vote, which was not ratified in all states until 1920 . Unable to participate in the most basic civic functions, women largely discussed politics only among themselves and were relegated to positions of lesser status in their personal and professional lives . Tri�es (1916) CHARACTERS

- 37. George Henderson, county attorney Mrs. Peters Henry Peters, sheriff Mrs. Hale Lewis Hale, a neighboring farmer SCENE The kitchen in the now abandoned farmhouse of John Wright, a gloomy kitchen, and left without having been put in order—unwashed pans under the sink, a loaf of bread outside the breadbox, a dish towel on the table—other signs of incom- pleted work. At the rear the outer door opens and the Sheriff comes in followed A P Im ag es 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S ,

- 38. M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S 868 Chapter 27 • Plot by the County Attorney and Hale. The Sheriff and Hale are men in middle life, the County Attorney is a young man; all are much bundled up and go at once to the stove. They are followed by two women—the Sheriff’s wife �rst; she is a slight wiry woman, a thin nervous face. Mrs. Hale is larger and would ordinarily be called more comfortable looking, but she is disturbed now and looks fearfully about as she enters. The women have come in slowly, and stand close together near the door. COUNTY ATTORNEY: (rubbing his hands) This feels good.

- 39. Come up to the �re, ladies. MRS. PETERS: (after taking a step forward) I’m not—cold. SHERIFF: (unbuttoning his overcoat and stepping away from the stove as if to mark the beginning of of�cial business) Now, Mr. Hale, before we move things about, you explain to Mr. Henderson just what you saw when you came here yesterday morning. COUNTY ATTORNEY: By the way, has anything been moved? Are things just as you left them yesterday? SHERIFF: (looking about) It’s just the same. When it dropped below zero last night I thought I’d better send Frank out this morning to make a �re for us—no use getting pneumonia with a big case on, but I told him not to touch anything except the stove—and you know Frank. COUNTY ATTORNEY: Somebody should have been left here yesterday. 5 In this scene from the Provincetown Players’ 1917 production of Susan Glaspell’s Trifles, the Trifles, the Trifles three men discuss the crime while Mrs. Peters and Mrs. Hale look on. Source: ©Billy Rose Theatre Collection, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lenox & Tilden

- 40. Foundations 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S Glaspell: Trifles 869 SHERIFF: Oh—yesterday. When I had to send Frank to Morris

- 41. Center for that man who went crazy—I want you to know I had my hands full yesterday. I knew you could get back from Omaha by today and as long as I went over everything here myself— COUNTY ATTORNEY: Well, Mr. Hale, tell just what happened when you came here yesterday morning. HALE: Harry and I had started to town with a load of potatoes. We came along the road from my place and as I got here I said, “I’m going to see if I can’t get John Wright to go in with me on a party telephone.” I spoke to Wright about it once before and he put me off, saying folks talked too much anyway, and all he asked was peace and quiet— I guess you know about how much he talked himself; but I thought maybe if I went to the house and talked about it before his wife, though I said to Harry that I didn’t know as what his wife wanted made much differ- ence to John— COUNTY ATTORNEY: Let’s talk about that later, Mr. Hale. I do want to talk about that, but tell now just what happened when you got to the house. HALE: I didn’t hear or see anything; I knocked at the door, and still it was

- 42. all quiet inside. I knew they must be up, it was past eight o’clock. So I knocked again, and I thought I heard somebody say, “Come in.” I wasn’t sure, I’m not sure yet, but I opened the door—this door (indicating the door by which the two women are still standing) and there in that rocker—(pointing to it) sat Mrs. Wright. They all look at the rocker. COUNTY ATTORNEY: What—was she doing? HALE: She was rockin’ back and forth. She had her apron in her hand and was kind of—pleating it. COUNTY ATTORNEY: And how did she—look? HALE: Well, she looked queer. COUNTY ATTORNEY: How do you mean—queer? HALE: Well, as if she didn’t know what she was going to do next. And kind of done up. COUNTY ATTORNEY: How did she seem to feel about your coming? HALE: Why, I don’t think she minded—one way or other. She didn’t pay much attention. I said, “How do, Mrs. Wright, it’s cold, ain’t it?” And she said, “Is it?”—and went on kind of pleating at her apron. Well, I was surprised; she didn’t ask me to come up to the stove, or to set down, but just sat there, not even looking at me, so I said, “I want to

- 43. see John.” And then she—laughed. I guess you would call it a laugh. I thought of Harry and the team outside, so I said a little sharp: “Can’t I see John?” “No,” she says, kind o’ dull like. “Ain’t he home?” says I. “Yes,” says she, “he’s home.” “Then why can’t I see him?” I asked her, 10 15 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1

- 44. 5 0 3 T S 870 Chapter 27 • Plot out of patience. “’Cause he’s dead,” says she. “Dead?” says I. She just nodded her head, not getting a bit excited, but rockin’ back and forth. “Why—where is he?” says I, not knowing what to say. She just pointed upstairs—like that. (Himself pointing to the room above.) I got up, with the idea of going up there. I walked from there to here—then I says, “Why, what did he die of?” “He died of a rope round his neck,” says she, and just went on pleatin’ at her apron. Well, I went out and called Harry. I thought I might—need help. We went upstairs and there he was lyin’— COUNTY ATTORNEY: I think I’d rather have you go into that upstairs, where you can point it all out. Just go on now with the rest of the story. HALE: Well, my �rst thought was to get that rope off. It looked . . . (stops,

- 45. his face twitches) . . . but Harry, he went up to him, and he said, “No, he’s dead all right, and we’d better not touch anything.” So we went back down stairs. She was still sitting that same way. “Has anybody been noti�ed?” I asked. “No,” says she, unconcerned. “Who did this, Mrs. Wright?” said Harry. He said it businesslike—and she stopped pleatin’ of her apron. “I don’t know,” she says. “You don’t know?” says Harry. “No,” says she. “Weren’t you sleepin’ in the bed with him?” says Harry. “Yes,” says she, “but I was on the inside.” “Somebody slipped a rope round his neck and strangled him and you didn’t wake up?” says Harry. “I didn’t wake up,” she said after him. We must ’a looked as if we didn’t see how that could be, for after a minute she said, “I sleep sound.” Harry was going to ask her more questions but I said maybe we ought to let her tell her story �rst to the coroner, or the sheriff, so Harry went fast as he could to Rivers’ place, where there’s a telephone. COUNTY ATTORNEY: And what did Mrs. Wright do when she knew that you had gone for the coroner? HALE: She moved from that chair to this one over here (pointing to a small

- 46. chair in the corner) and just sat there with her hands held together and looking down. I got a feeling that I ought to make some conversation, so I said I had come in to see if John wanted to put in a telephone, and at that she started to laugh, and then she stopped and looked at me—scared. (The County Attorney, who has had his notebook out, makes a note.) I dunno, maybe it wasn’t scared. I wouldn’t like to say it was. Soon Harry got back, and then Dr. Lloyd came, and you, Mr. Peters, and so I guess that’s all I know that you don’t. COUNTY ATTORNEY: (looking around) I guess we’ll go upstairs �rst—and then out to the barn and around there. (To the Sheriff.) You’re con- vinced that there was nothing important here—nothing that would point to any motive. 20 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S

- 47. , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S Glaspell: Trifles 871 SHERIFF: Nothing here but kitchen things. The County Attorney, after again looking around the kitchen, opens the door of a cupboard closet. He gets up on a chair and looks on a shelf. Pulls his hand away, sticky. COUNTY ATTORNEY: Here’s a nice mess. The women draw nearer. MRS. PETERS: (to the other woman) Oh, her fruit; it did

- 48. freeze. (To the County Attorney.) She worried about that when it turned so cold. She said the �re’d go out and her jars would break. SHERIFF: Well, can you beat the women! Held for murder and worryin’ about her preserves. COUNTY ATTORNEY: I guess before we’re through she may have something more serious than preserves to worry about. HALE: Well, women are used to worrying over tri�es. The two women move a little closer together. COUNTY ATTORNEY: (with the gallantry of a young politician) And yet, for all their worries, what would we do without the ladies? (The women do not unbend. He goes to the sink, takes a dipperful of water from the pail and pouring it into a basin, washes his hands. Starts to wipe them on the roller towel, turns it for a cleaner place.) Dirty towels! (Kicks his foot against the pans under the sink.) Not much of a housekeeper, would you say, ladies? MRS. HALE: (stif�y) There’s a great deal of work to be done on a farm. COUNTY ATTORNEY: To be sure. And yet (with a little bow to her) I know there are some Dickson county farmhouses which do not have

- 49. such roller towels. He gives it a pull to expose its full length again. MRS. HALE: Those towels get dirty awful quick. Men’s hands aren’t always as clean as they might be. COUNTY ATTORNEY: Ah, loyal to your sex, I see. But you and Mrs. Wright were neighbors. I suppose you were friends, too. MRS. HALE: (shaking her head) I’ve not seen much of her of late years. I’ve not been in this house—it’s more than a year. COUNTY ATTORNEY: And why was that? You didn’t like her? MRS. HALE: I liked her all well enough. Farmers’ wives have their hands full, Mr. Henderson. And then— COUNTY ATTORNEY: Yes—? MRS. HALE: (looking about) It never seemed a very cheerful place. COUNTY ATTORNEY: No—it’s not cheerful. I shouldn’t say she had the homemaking instinct. 25 30 35

- 50. 40 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S 872 Chapter 27 • Plot MRS. HALE: Well, I don’t know as Wright had, either.

- 51. COUNTY ATTORNEY: You mean that they didn’t get on very well? MRS. HALE: No, I don’t mean anything. But I don’t think a place’d be any cheerfuller for John Wright’s being in it. COUNTY ATTORNEY: I’d like to talk more of that a little later. I want to get the lay of things upstairs now. He goes to the left, where three steps lead to a stair door. SHERIFF: I suppose anything Mrs. Peters does’ll be all right. She was to take in some clothes for her, you know, and a few little things. We left in such a hurry yesterday. COUNTY ATTORNEY: Yes, but I would like to see what you take, Mrs. Peters, and keep an eye out for anything that might be of use to us. MRS. PETERS: Yes, Mr. Henderson. The women listen to the men’s steps on the stairs, then look about the kitchen. MRS. HALE: I’d hate to have men coming into my kitchen, snooping around and criticizing. She arranges the pans under sink which the County Attorney had shoved out of place.

- 52. MRS. PETERS: Of course it’s no more than their duty. MRS. HALE: Duty’s all right, but I guess that deputy sheriff that came out to make the �re might have got a little of this on. (Gives the roller towel a pull.) Wish I’d thought of that sooner. Seems mean to talk about her for not having things slicked up when she had to come away in such a hurry. MRS. PETERS: (who has gone to a small table in the left rear corner of the room, and lifted one end of a towel that covers a pan) She had bread set. Stands still. MRS. HALE: (eyes �xed on a loaf of bread beside the breadbox, which is on a low shelf at the other side of the room. Moves slowly toward it.) She was going to put this in there. (Picks up loaf, then abruptly drops it. In a manner of returning to familiar things.) It’s a shame about her fruit. I wonder if it’s all gone. (Gets up on the chair and looks.) I think there’s some here that’s all right, Mrs. Peters. Yes—here; (holding it toward the window) this is cherries, too. (Looking again.) I declare I believe that’s the only one. (Gets down, bottle in her hand. Goes to the sink and

- 53. wipes it off on the outside.) She’ll feel awful bad after all her hard work in the hot weather. I remember the afternoon I put up my cherries last summer. 45 50 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3

- 54. T S Glaspell: Trifles 873 She puts the bottle on the big kitchen table, center of the room. With a sigh, is about to sit down in the rocking-chair. Before she is seated realizes what chair it is; with a slow look at it, steps back. The chair which she has touched rocks back and forth. MRS. PETERS: Well, I must get those things from the front room closet. (She goes to the door at the right, but after looking into the other room, steps back.) You coming with me, Mrs. Hale? You could help me carry them. They go in the other room; reappear, Mrs. Peters carrying a dress and skirt, Mrs. Hale following with a pair of shoes. MRS. PETERS: My, it’s cold in there. She puts the clothes on the big table, and hurries to the stove. MRS. HALE: (examining her skirt) Wright was close. I think maybe that’s why she kept so much to herself. She didn’t even belong to the Ladies Aid. I suppose she felt she couldn’t do her part, and then you don’t enjoy things when you feel shabby. She used to wear pretty

- 55. clothes and be lively, when she was Minnie Foster, one of the town girls singing in the choir. But that—oh, that was thirty years ago. This all you was to take in? MRS. PETERS: She said she wanted an apron. Funny thing to want, for there isn’t much to get you dirty in jail, goodness knows. But I suppose just to make her feel more natural. She said they was in the top drawer in this cupboard. Yes, here. And then her little shawl that always hung behind the door. (Opens stair door and looks.) Yes, here it is. Quickly shuts door leading upstairs. MRS. HALE: (abruptly moving toward her) Mrs. Peters? MRS. PETERS: Yes, Mrs. Hale? MRS. HALE: Do you think she did it? MRS. PETERS: (in a frightened voice) Oh, I don’t know. MRS. HALE: Well, I don’t think she did. Asking for an apron and her little shawl. Worrying about her fruit. MRS. PETERS: (starts to speak, glances up, where footsteps are heard in the room above. In a low voice.) Mr. Peters says it looks bad for her. Mr. Henderson is awful sarcastic in a speech and he’ll make fun of her sayin’ she didn’t wake up.

- 56. MRS. HALE: Well, I guess John Wright didn’t wake when they was slipping that rope under his neck. MRS. PETERS: No, it’s strange. It must have been done awful crafty and still. They say it was such a—funny way to kill a man, rigging it all up like that. MRS. HALE: That’s just what Mr. Hale said. There was a gun in the house. He says that’s what he can’t understand. 55 60 65 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V

- 57. E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S 874 Chapter 27 • Plot MRS. PETERS: Mr. Henderson said coming out that what was needed for the case was a motive; something to show anger, or—sudden feeling. MRS. HALE: (who is standing by the table) Well, I don’t see any signs of anger around here. (She puts her hand on the dish towel which lies on the table, stands looking down at table, one half of which is clean, the other half messy.) It’s wiped to here. (Makes a move as if to �nish work, then turns and looks at loaf of bread outside the breadbox. Drops towel. In that voice of coming back to familiar things.) Wonder how they are �nding things upstairs. I hope she had it a little more red-up1 up there. You know, it

- 58. seems kind of sneaking. Locking her up in town and then coming out here and trying to get her own house to turn against her! MRS. PETERS: But Mrs. Hale, the law is the law. MRS. HALE: I s’pose ’tis. (Unbuttoning her coat.) Better loosen up your things, Mrs. Peters. You won’t feel them when you go out. Mrs. Peters takes off her fur tippet, goes to hang it on hook at back of room, stands looking at the under part of the small corner table. MRS. PETERS: She was piecing a quilt. She brings the large sewing basket and they look at the bright pieces. MRS. HALE: It’s log cabin pattern. Pretty, isn’t it? I wonder if she was goin’ to quilt it or just knot it? Footsteps have been heard coming down the stairs. The Sheriff enters followed by Hale and the County Attorney. SHERIFF: They wonder if she was going to quilt it or just knot it! The men laugh; the women look abashed. COUNTY ATTORNEY: (rubbing his hands over the stove) Frank’s �re didn’t do much up there, did it? Well, let’s go out to the barn and get that

- 59. cleared up. The men go outside. MRS. HALE: (resentfully) I don’t know as there’s anything so strange, our takin’ up our time with little things while we’re waiting for them to get the evidence. (She sits down at the big table smoothing out a block with decision.) I don’t see as it’s anything to laugh about. MRS. PETERS: (apologetically) Of course they’ve got awful important things on their minds. 70 75 ●● 1red-up: Spruced-up (slang) .red-up: Spruced-up (slang) .red- up: 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S ,

- 60. M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S Glaspell: Trifles 875 Pulls up a chair and joins Mrs. Hale at the table. MRS. HALE: (examining another block) Mrs. Peters, look at this one. Here, this is the one she was working on, and look at the sewing! All the rest of it has been so nice and even. And look at this! It’s all over the place! Why, it looks as if she didn’t know what she was about! After she has said this they look at each other, then start to glance back at the door. After an instant Mrs. Hale has pulled at a knot and ripped the sewing.

- 61. MRS. PETERS: Oh, what are you doing, Mrs. Hale? MRS. HALE: (mildly) Just pulling out a stitch or two that’s not sewed very good. (Threading a needle.) Bad sewing always made me �dgety. MRS. PETERS: (nervously) I don’t think we ought to touch things. MRS. HALE: I’ll just �nish up this end. (Suddenly stopping and leaning forward.) Mrs. Peters? MRS. PETERS: Yes, Mrs. Hale? MRS. HALE: What do you suppose she was so nervous about? MRS. PETERS: Oh—I don’t know. I don’t know as she was nervous. I sometimes sew awful queer when I’m just tired. (Mrs. Hale starts to say something, looks at Mrs. Peters, then goes on sewing.) Well, I must get these things wrapped up. They may be through sooner than we think. (Putting apron and other things together.) I wonder where I can �nd a piece of paper, and string. MRS. HALE: In that cupboard, maybe. MRS. PETERS: (looking in cupboard) Why, here’s a birdcage. (Holds it up.) Did she have a bird, Mrs. Hale? MRS. HALE: Why, I don’t know whether she did or not—I’ve not been

- 62. here for so long. There was a man around last year selling canaries cheap, but I don’t know as she took one; maybe she did. She used to sing real pretty herself. MRS. PETERS: (glancing around) Seems funny to think of a bird here. But she must have had one, or why would she have a cage? I wonder what happened to it. MRS. HALE: I s’pose maybe the cat got it. MRS. PETERS: No, she didn’t have a cat. She’s got that feeling some people have about cats—being afraid of them. My cat got in her room and she was real upset and asked me to take it out. MRS. HALE: My sister Bessie was like that. Queer, ain’t it? MRS. PETERS: (examining the cage) Why, look at this door. It’s broke. One hinge is pulled apart. MRS. HALE: (looking too) Looks as if someone must have been rough with it. MRS. PETERS: Why, yes. 80 85 90

- 63. 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S 876 Chapter 27 • Plot She brings the cage forward and puts it on the table.

- 64. MRS. HALE: I wish if they’re going to �nd any evidence they’d be about it. I don’t like this place. MRS. PETERS: But I’m awful glad you came with me, Mrs. Hale. It would be lonesome for me sitting here alone. MRS. HALE: It would, wouldn’t it? (Dropping her sewing.) But I tell you what I do wish, Mrs. Peters. I wish I had come over sometimes when she was here. I—(looking around the room)—wish I had. MRS. PETERS: But of course you were awful busy, Mrs. Hale—your house and your children. MRS. HALE: I could’ve come. I stayed away because it weren’t cheerful— and that’s why I ought to have come. I—I’ve never liked this place. Maybe because it’s down in a hollow and you don’t see the road. I dunno what it is but it’s a lonesome place and always was. I wish I had come over to see Minnie Foster sometimes. I can see now— Shakes her head. MRS. PETERS: Well, you mustn’t reproach yourself, Mrs. Hale. Somehow we just don’t see how it is with other folks until—something comes up.

- 65. MRS. HALE: Not having children makes less work—but it makes a quiet house, and Wright out to work all day, and no company when he did come in. Did you know John Wright, Mrs. Peters? 95 100 In this scene from a 2010 production of Susan Glaspell’s Trifles, Mrs. Peters and Mrs. Hale Trifles, Mrs. Peters and Mrs. Hale Trifles discuss the discovery of a birdcage. P ru d e n c e Ka tze 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N

- 66. E 1 5 0 3 T S Glaspell: TriflesGlaspell: TriflesGlaspell: T 877 MRS. PETERS: Not to know him; I’ve seen him in town. They say he was a good man. MRS. HALE: Yes—good; he didn’t drink, and kept his word as well as most, I guess, and paid his debts. But he was a hard man, Mrs. Peters. Just to pass the time of day with him—(Shivers.) Like a raw wind that gets to the bone. (Pauses, her eye falling on the cage.) I should think she would ’a wanted a bird. But what do you suppose went with it? MRS. PETERS: I don’t know, unless it got sick and died. She reaches over and swings the broken door, swings it again. Both women watch it. MRS. HALE: You weren’t raised round here, were you? (Mrs. Peters shakes her head.) You didn’t know—her?

- 67. MRS. PETERS: Not till they brought her yesterday. MRS. HALE: She—come to think of it, she was kind of like a bird herself— real sweet and pretty, but kind of timid and—�uttery. How— she— did—change. (Silence; then as if struck by a happy thought and relieved to get back to everyday things.) Tell you what, Mrs. Peters, why don’t you take the quilt in with you? It might take up her mind. MRS. PETERS: Why, I think that’s a real nice idea, Mrs. Hale. There couldn’t possibly be any objection to it, could there? Now, just what would I take? I wonder if her patches are in here—and her things. They look in the sewing basket. MRS. HALE: Here’s some red. I expect this has got sewing things in it. (Brings out a fancy box.) What a pretty box. Looks like something somebody would give you. Maybe her scissors are in here. (Opens box. Suddenly puts her hand to her nose.) Why—(Mrs. Peters bends nearer, then turns her face away.) There’s something wrapped up in this piece of silk. MRS. PETERS: Why, this isn’t her scissors. MRS. HALE: (lifting the silk) Oh, Mrs. Peters—it’s— Mrs. Peters bends closer.

- 68. MRS. PETERS: It’s the bird. MRS. HALE: (jumping up) But, Mrs. Peters—look at it! Its neck! Look at its neck! It’s all—other side to. MRS. PETERS: Somebody—wrung—its—neck. Their eyes meet. A look of growing comprehension, of horror. Steps are heard outside. Mrs. Hale slips the box under quilt pieces, and sinks into her chair. Enter Sheriff and County Attorney. Mrs. Peters rises. COUNTY ATTORNEY: (as one turning from serious things to little pleasantries) Well, ladies, have you decided whether she was going to quilt it or knot it? 105 110 115 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S

- 69. , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S 878 Chapter 27 • Plot MRS. PETERS: We think she was going to—knot it. COUNTY ATTORNEY: Well, that’s interesting, I’m sure. (Seeing the birdcage.) Has the bird �own? MRS. HALE: (putting more quilt pieces over the box) We think the—cat got it. COUNTY ATTORNEY: (preoccupied) Is there a cat? Mrs. Hale glances in a quick covert way at Mrs. Peters. MRS. PETERS: Well, not now. They’re superstitious, you know. They leave.

- 70. COUNTY ATTORNEY: (to Sheriff Peters, continuing an interrupted conversa- tion) No sign at all of anyone having come from the outside. Their own rope. Now let’s go up again and go over it piece by piece. (They start upstairs.) It would have to have been someone who knew just the— Mrs. Peters sits down. The two women sit there not looking at one another, but as if peering into something and at the same time holding back. When they talk now it is in the manner of feeling their way over strange ground, as if afraid of what they are saying, but as if they can not help saying it. MRS. HALE: She liked the bird. She was going to bury it in that pretty box. MRS. PETERS: (in a whisper) When I was a girl—my kitten— there was a boy took a hatchet, and before my eyes—and before I could get there—(Covers her face an instant.) If they hadn’t held me back I would have—(catches herself, looks upstairs where steps are heard, falters weakly)—hurt him. MRS. HALE: (with a slow look around her) I wonder how it would seem never to have had any children around. (Pause.) No, Wright wouldn’t like the bird—a thing that sang. She used to sing. He killed that,

- 71. too. MRS. PETERS: (moving uneasily) We don’t know who killed the bird. MRS. HALE: I knew John Wright. MRS. PETERS: It was an awful thing was done in this house that night, Mrs. Hale. Killing a man while he slept, slipping a rope around his neck that choked the life out of him. MRS. HALE: His neck. Choked the life out of him. Her hand goes out and rests on the birdcage. MRS. PETERS: (with rising voice) We don’t know who killed him. We don’t know. MRS. HALE: (her own feeling not interrupted) If there’d been years and years of nothing, then a bird to sing to you, it would be awful—still, after the bird was still. MRS. PETERS: (something within her speaking) I know what stillness is. When we homesteaded in Dakota, and my �rst baby died—after he was two years old, and me with no other then— 120 125

- 72. 130 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S Glaspell: Trifles 879 MRS. HALE: (moving) How soon do you suppose they’ll be

- 73. through, looking for the evidence? MRS. PETERS: I know what stillness is. (Pulling herself back.) The law has got to punish crime, Mrs. Hale. MRS. HALE: (not as if answering that) I wish you’d seen Minnie Foster when she wore a white dress with blue ribbons and stood up there in the choir and sang. (A look around the room.) Oh, I wish I’d come over here once in a while! That was a crime! That was a crime! Who’s going to punish that? MRS. PETERS: (looking upstairs) We mustn’t—take on. MRS. HALE: I might have known she needed help! I know how things can be—for women. I tell you, it’s queer, Mrs. Peters. We live close together and we live far apart. We all go through the same things—it’s all just a different kind of the same thing. (Brushes her eyes; noticing the bottle of fruit, reaches out for it.) If I was you I wouldn’t tell her her fruit was gone. Tell her it ain’t. Tell her it’s all right. Take this in to prove it to her. She—she may never know whether it was broke or not. MRS. PETERS: (takes the bottle, looks about for something to wrap it in; takes petticoat from the clothes brought from the other room, very

- 74. nervously begins winding this around the bottle. In a false voice) My, it’s a good thing the men couldn’t hear us. Wouldn’t they just laugh! Getting all stirred up over a little thing like a—dead canary. As if that could have anything to do with—with—wouldn’t they laugh! The men are heard coming down stairs. MRS. HALE: (under her breath) Maybe they would—maybe they wouldn’t. COUNTY ATTORNEY: No, Peters, it’s all perfectly clear except a reason for doing it. But you know juries when it comes to women. If there was some de�nite thing. Something to show—something to make a story about—a thing that would connect up with this strange way of doing it— The women’s eyes meet for an instant. Enter Hale from outer door. HALE: Well, I’ve got the team around. Pretty cold out there. COUNTY ATTORNEY: I’m going to stay here a while by myself. (To the Sher- iff.) You can send Frank out for me, can’t you? I want to go over every- thing. I’m not satis�ed that we can’t do better. SHERIFF: Do you want to see what Mrs. Peters is going to take in?

- 75. The County Attorney goes to the table, picks up the apron, laughs. COUNTY ATTORNEY: Oh, I guess they’re not very dangerous things the ladies have picked out. (Moves a few things about, disturbing the quilt pieces which cover the box. Steps back.) No, Mrs. Peters doesn’t need 135 140 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E

- 76. 1 5 0 3 T S 880 Chapter 27 • Plot supervising. For that matter, a sheriff’s wife is married to the law. Ever think of it that way, Mrs. Peters? MRS. PETERS: Not—just that way. SHERIFF: (chuckling) Married to the law. (Moves toward the other room.) I just want you to come in here a minute, George. We ought to take a look at these windows. COUNTY ATTORNEY: (scof�ngly) Oh, windows! SHERIFF: We’ll be right out, Mr. Hale. Hale goes outside. The Sheriff follows the County Attorney into the other room. Then Mrs. Hale rises, hands tight together, looking intensely at Mrs. Peters, whose eyes make a slow turn, �nally meeting Mrs. Hale’s. A moment Mrs. Hale holds her, then her own eyes point the way to where the box is concealed. Sud- denly Mrs. Peters throws back quilt pieces and tries to put the box in the bag she

- 77. is wearing. It is too big. She opens box, starts to take bird out, cannot touch it, goes to pieces, stands there helpless. Sound of a knob turning in the other room. Mrs. Hale snatches the box and puts it in the pocket of her big coat. Enter County Attorney and Sheriff. COUNTY ATTORNEY: (facetiously) Well, Henry, at least we found out that she was not going to quilt it. She was going to—what is it you call it, ladies? MRS. HALE: (her hand against her pocket) We call it—knot it, Mr. Henderson. * * * Reading and Reacting 1. What key events have occurred before the start of the play? Why do you suppose these events are not presented in the play itself? 2. What are the “tri�es” to which the title refers? How do these “tri�es” advance the play’s plot? 3. Glaspell’s short story version of Tri�es is called “A Jury of Her Peers.” Who are Mrs. Wright’s peers? What do you suppose the verdict would be if she were tried for her crime in 1916, when only men were permit- ted to serve on juries? If the trial were held today, do you think a jury

- 78. might reach a different verdict? What would your own verdict be? Do you think Mrs. Hale and Mrs. Peters do the right thing by concealing the evidence? 4. Tri�es is a one-act play, and all its action occurs in the Wrights’ kitchen. What do you see as the advantages and disadvantages of this con�ned setting? 5. All background information about Mrs. Wright is provided by Mrs. Hale. Do you consider her to be a reliable source of information? Explain. 6. Mr. Hale’s summary of his conversation with Mrs. Wright is the reader’s only chance to hear her version of events. How might the play be differ- ent if Mrs. Wright appeared as a character? 145 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S ,

- 79. M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S Ibsen: A Doll House 881 7. How does each of the following events advance the play’s action: the men’s departure from the kitchen, the discovery of the quilt pieces, the discovery of the dead bird? 8. What assumptions about women do the male characters make? In what ways do the female characters support or challenge these assumptions? 9. JOURNAL ENTRY In what sense is the process of making a quilt an appropriNTRY In what sense is the process of making a quilt an appropriNTRY -

- 80. ate metaphor for the plot of Tri�es? 10. CRITICAL PERSPECTIVE In American Drama from the Colonial Period through World War I, Gary A. Richardson says that in Tri�es, Glaspell developed a new structure for her action: While action in the traditional sense is minimal, Glaspell is nevertheless able to rivet attention on the two women, wed the audience to their perspective, and make a compelling case for the fairness of their actions. Existing on the margins of their society, Mrs. Peters and Mrs. Hale become emotional sur- rogates for the jailed Minnie Wright, effectively exonerating her action as “justi�able homicide.” Tri�es is carefully crafted to match Glaspell’s subject matter— the action meanders, without a clearly delineated beginning, middle, or end. . . . Exactly how does Glaspell “rivet attention on” Mrs. Hale and Mrs. Peters? In what sense is the play’s “meandering” structure “carefully crafted to match Glaspell’s subject matter”? Related Works: “I Stand Here Ironing” (p. 217), “Everyday Use” (p. 344), “The Yellow Wallpaper” (p. 434), “Harlem” (p. 577), “Daddy” (p. 589), A Doll House (p. 881)

- 81. HENRIK IBSEN (1828–1906), Norway’s foremost dramatist, was born into a prosperous family; however, his father lost his fortune when Ibsen was six . When Ibsen was fifteen, he was apprenticed to an apothecary away from home and was per- manently estranged from his family . During his apprenticeship, he studied to enter the university and wrote plays . Although he did not pass the university entrance exam, his second play, The Warrior’s Barrow (1850), was produced by the The Warrior’s Barrow (1850), was produced by the The Warrior’s Barrow Christiania Theatre in 1850 . He began a life in the theater, writing plays and serving as artistic director of a theatrical company . Disillusioned by the public’s lack of interest in theater, he left Norway, living with his wife and son in Italy and Germany between 1864 and 1891 . By the time he returned to Norway, he was famous and revered . Ibsen’s most notable plays include Brand (1865), Brand (1865), Brand Peer Gynt (1867), Peer Gynt (1867), Peer Gynt A Doll House (1879), A Doll House (1879), A Doll House Ghosts (1881), Ghosts (1881), Ghosts An Enemy of the People (1882), An Enemy of the People (1882), An Enemy of the People The Wild Duck (1884), The Wild Duck (1884), The Wild Duck Hedda Gabler (1890), and Hedda Gabler (1890), and Hedda Gabler When We Dead Awaken (1899) .When We Dead Awaken (1899) .When We Dead Awaken A Doll House marks the beginning of Ibsen’s successful realist period, during which he A Doll House marks the beginning of Ibsen’s successful realist period, during which he A Doll House explored the ordinary lives of small-town people—in this case, writing what he called “a H

- 82. ul to n A rc hi ve /S tr in ge r/ G et ty Im ag es 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N

- 83. E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S 882 Chapter 27 • Plot modern tragedy .” Ibsen based the play on a true story, which closely paralleled the main events of the play: a wife borrows money to finance a trip for an ailing husband, repayment is de- manded, she forges a check and is discovered . (In the real-life story, however, the husband demanded a divorce, and the wife had a nervous breakdown and was committed to a mental institution .) The issue in A Doll House, he said, is that there are “two kinds of moral law, . . . one in man and a completely different one in woman . They do

- 84. not understand each other . . . .” Nora and Helmer’s marriage is destroyed because they cannot comprehend or accept their dif- ferences . The play begins conventionally but does not fulfill the audience’s expectations for a tidy resolution; as a result, it was not a success when it was first performed . Nevertheless, the publication of A Doll House made Ibsen internationally famous .A Doll House made Ibsen internationally famous .A Doll House Cultural Context During the nineteenth century, the law treated women only a little better than it treated children . Women could not vote, and they were not considered able to handle their own financial affairs . A woman could not borrow money in her own name, and when she married, her finances were placed under the control of her husband . Moreover, working outside the home was out of the question for a middle-class woman . So, if a woman were to leave her husband, she was not likely to have any way of supporting herself, and she would lose the custody of her children . At the time when A Doll House was first performed, most A Doll House was first performed, most A Doll House viewers were offended by the way Nora spoke to her husband, and Ibsen was considered an anarchist for suggesting that a woman could leave her family in search of herself . However, Ibsen argued that he was merely asking people to look at, and think about, the social structure they supported . A Doll House (1879) Translated by Rolf Fjelde

- 85. CHARACTERS Torvald Helmer, a lawyer Nils Krogstad, a bank clerk Nora, his wife The Helmers’ three small children Dr. Rank Anne-Marie, their nurse Mrs. Linde Helene, a maid A Delivery Boy The action takes place in Helmer’s residence. ACT 1 A comfortable room, tastefully but not expensively furnished. A door to the right in the back wall leads to the entryway; another to the left leads to Helmer’s study. Between these doors, a piano. Midway in the left-hand wall a door, and further back a window. Near the window a round table with an armchair and a small sofa. In the right-hand wall, toward the rear, a door, and nearer the foreground a porcelain stove with two armchairs and a rocking chair beside it. Between the stove and the side door, a small table. Engravings on the walls. An étagère with china �gures and other small art objects; a small bookcase with richly bound books; the �oor carpeted; a �re burning in the stove. It is a winter day. 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization.

- 86. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3 T S Ibsen: A Doll House Act 1 883 A bell rings in the entryway; shortly after we hear the door being unlocked. Nora comes into the room, humming happily to herself; she is wearing street clothes and carries an armload of packages, which she puts down on the table to the right. She has left the hall door open; and through it a Delivery Boy is seen, holding a

- 87. Christmas tree and a basket, which he gives to the Maid who let them in. NORA: Hide the tree well, Helene. The children mustn’t get a glimpse of it till this evening, after it’s trimmed. (To the Delivery Boy, taking out her purse.) How much? DELIVERY BOY: Fifty, ma’am. NORA: There’s a crown. No, keep the change. (The Boy thanks her and leaves. Nora shuts the door. She laughs softly to herself while taking off her street things. Drawing a bag of macaroons from her pocket, she eats a couple, then steals over and listens at her husband’s study door.) Yes, he’s home. (Hums again as she moves to the table right.) HELMER: (from the study) Is that my little lark twittering out there? NORA: (busy opening some packages) Yes, it is. HELMER: Is that my squirrel rummaging around? NORA: Yes! HELMER: When did my squirrel get in? NORA: Just now. (Putting the macaroon bag in her pocket and wiping her mouth.) Do come in, Torvald, and see what I’ve bought. HELMER: Can’t be disturbed. (After a moment he opens the door and peers in, pen in hand.) Bought, you say? All that there? Has the little spendthrift

- 88. been out throwing money around again? NORA: Oh, but Torvald, this year we really should let ourselves go a bit. It’s the �rst Christmas we haven’t had to economize. HELMER: But you know we can’t go squandering. NORA: Oh yes, Torvald, we can squander a little now. Can’t we? Just a tiny, wee bit. Now that you’ve got a big salary and are going to make piles and piles of money. HELMER: Yes—starting New Year’s. But then it’s a full three months till the raise comes through. NORA: Pooh! We can borrow that long. HELMER: Nora! (Goes over and playfully takes her by the ear.) Are your scat- terbrains off again? What if today I borrowed a thousand crowns, and you squandered them over Christmas week, and then on New Year’s Eve a roof tile fell on my head, and I lay there— NORA: (putting her hand on his mouth) Oh! Don’t say such things! HELMER: Yes, but what if it happened—then what? NORA: If anything so awful happened, then it just wouldn’t matter if I had debts or not. HELMER: Well, but the people I’d borrowed from?

- 89. NORA: Them? Who cares about them! They’re strangers. 5 10 15 20 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E 1 5 0 3

- 90. T S 884 Chapter 27 • Plot HELMER: Nora, Nora, how like a woman! No, but seriously, Nora, you know what I think about that. No debts! Never borrow! Something of free- dom’s lost—and something of beauty, too—from a home that’s founded on borrowing and debt. We’ve made a brave stand up to now, the two of us; and we’ll go right on like that the little while we have to. NORA: (going toward the stove) Yes, whatever you say, Torvald. HELMER: (following her) Now, now, the little lark’s wings mustn’t droop. Come on, don’t be a sulky squirrel. (Taking out his wallet.) Nora, guess what I have here. NORA: (turning quickly) Money! HELMER: There, see. (Hands her some notes.) Good grief, I know how costs go up in a house at Christmastime. NORA: Ten—twenty—thirty—forty. Oh, thank you, Torvald; I can man- age no end on this. HELMER: You really will have to.

- 91. NORA: Oh yes, I promise I will! But come here so I can show you every- thing I bought. And so cheap! Look, new clothes for Ivar here— and a 25 Scene from A Doll House with Toby Stephens (as Torvald A Doll House with Toby Stephens (as Torvald A Doll House Helmer) and Gillian Anderson (as Nora) at The Donmar Warehouse, London, UK in May 2009 Source: Nigel Norrington/ArenaPal/TopFoto/The Image Works 9781337509633, PORTABLE Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing, Ninth edition, Kirszner - © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express authorization. J O N E S , M E L V E R I N E

- 92. 1 5 0 3 T S Ibsen: A Doll House Act 1 885 sword. Here a horse and a trumpet for Bob. And a doll and a doll’s bed here for Emmy; they’re nothing much, but she’ll tear them to bits in no time anyway. And here I have dress material and handkerchiefs for the maids. Old Anne-Marie really deserves something more. HELMER: And what’s in that package there? NORA: (with a cry) Torvald, no! You can’t see that till tonight! HELMER: I see. But tell me now, you little prodigal, what have you thought of for yourself? NORA: For myself? Oh, I don’t want anything at all. HELMER: Of course you do. Tell me just what—within reason—you’d most like to have. NORA: I honestly don’t know. Oh, listen, Torvald— HELMER: Well? NORA: (fumbling at his coat buttons, without looking at him) If you want to give me something, then maybe you could—you could—

- 93. HELMER: Come on, out with it. NORA: (hurriedly) You could give me money, Torvald. No more than you think you can spare; then one of these days I’ll buy something with it. HELMER: But Nora— NORA: Oh, please, Torvald darling, do that! I beg you, please. Then I could hang the bills in pretty gilt paper on the Christmas tree. Wouldn’t that be fun? HELMER: What are those little birds called that always �y through their fortunes? NORA: Oh yes, spendthrifts; I know all that. But let’s do as I say, Torvald; then I’ll have time to decide what I really need most. That’s very sen- sible, isn’t it? HELMER: (smiling) Yes, very—that is, if you actually hung onto the money I give you, and you actually used it to buy yourself something. But it goes for the house and for all sorts of foolish things, and then I only have to lay out some more. NORA: Oh, but Torvald— HELMER: Don’t deny it, my dear little Nora. (Putting his arm around her