HSC 312 Final Project –Complied Case Analysis Scoring Rubr.docx

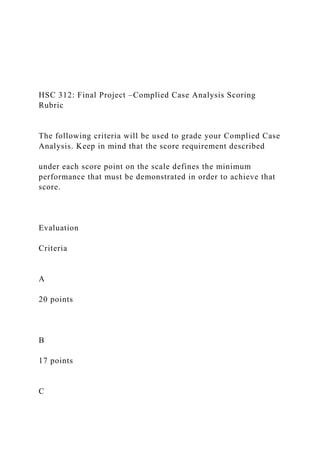

- 1. HSC 312: Final Project –Complied Case Analysis Scoring Rubric The following criteria will be used to grade your Complied Case Analysis. Keep in mind that the score requirement described under each score point on the scale defines the minimum performance that must be demonstrated in order to achieve that score. Evaluation Criteria A 20 points B 17 points C

- 2. 15 points D 13 points F 11 points 1.) Introduces the case analysis by describing the ethical dilemma requiring resolution Introduction is: • Comprehensive • Includes a thorough, clear and

- 3. concise description of the case and ethical dilemma proposed. Introduction: • Includes minor omissions in description of either the case or ethical dilemma. Introduction: • Lacks detail in part • Includes minor omissions in both the

- 4. description of the case and the ethical dilemma. Introduction: • Lacks detail • Includes major omissions in either description of the case or the ethical dilemma. Description is either missing or contains major omissions throughout. 2.) Identifies the

- 5. primary stakeholder (s) and provides a description of the situation from the stakeholder perspective Description is: • Comprehensive • Includes identification of stakeholder • Provides clear stakeholder Description:

- 6. • Has minor omissions or errors in identification of stakeholders or in describing the stakeholder perspective. Description: • Lacks detail • Omits some significant content or contains several minor errors. Description:

- 7. • Lacks detail. • Is superficial and contains multiple errors. Description is: • Missing or incorrect • Inconsistent with selected stakeholder identify any or identifies irrelevant stakeholders. 3.) Analyzes the scenario

- 8. from the perspective of the primary stakeholder and includes a description of at least two ethical theories that relate to the issue being identified Analysis and Description are: • Comprehensive • Include responses to all

- 9. subcomponents of the question. • Provides clear description of two or more ethical theories and their relation to the issue. Analysis and Description: • Include minor omissions. • Includes 1-2 minor errors in regards to the scenario of the stakeholder or the description

- 10. of the ethical theories. Analysis and Description: • Include a major omission, OR • Includes several errors in regards to the scenario of the stakeholder or the description of the ethical theories. Analysis and Description: • Includes a major omission,

- 11. AND • Includes several errors in regards to the scenario of the stakeholder or the description of the ethical theories. Analysis and Description are: • Missing OR • Response contains significant errors or omissions

- 12. throughout the response. 4.) Provides a reasonable recommendat ion based upon the analysis presented Recommendation is: • Comprehensive. • Clear and logical • Summarizes key points. Recommendation has: • Minor omissions or

- 13. errors • Is clear and logical • Summarizes most key points. Recommendation: • Omits some significant content and contains several minor errors • Is clear or logical but not both • Summarizes minimal points. Recommendation:

- 14. • Is superficial and contains multiple errors • Is not clear or logical • Summarizes 1- 2 points. Recommendation is: • Missing or incorrect. 5.) Format Format is: • Clear and consistent. • contains accurate and proper

- 15. grammatical conventions, spelling, formatting, and referencing. • Follows specific instructions. Format is: • Clear and mostly consistent. • Contains few errors of accuracy • Follows specific instructions with minor

- 16. omissions. Format is: • Clear but not concise. • Contains multiple errors of accuracy. • Follows specific instructions with multiple omissions. Format is: • Not clear or concise. • Contains serious errors. • Specific

- 17. instructions are barely followed. Format: • Is not clear. • Does not follow specific instructions. Final Project – Compiled Case Studies Jane Doe HSC312 May 2013 Professor X

- 18. HSC312 - Final Project: Compiled Case Studies May 2013 Jane Doe Case Analysis: Sally & the DNR Case Analysis Template for use with each of the four scenarios in the final project: 1. Copy/paste the title of the question 2. Describe the most relevant ethical dilemma(s) presented (no more than two). 3. Briefly describe the primary issue or issues that are relevant in the scenario w/respect to the dilemma. 4. Identify the most relevant stakeholder(s) (no more than 3) and briefly describe the situation from their perspective. 5. Analyze the dilemma, using scholarly discussion, from the perspective of the primary stakeholder (typically the patient). Include a discussion of at least two ethical theories or bioethics principles studied in the course that relate to the

- 19. dilemma and issues you identified. Include any relevant legal concerns or requirements outlined in the readings. 6. Present your assessment, resolution or potential solutions for resolving the issue. Remember that there are no right answers, per se, so reflective questions can be as appropriate as a firm conclusion. 7. Title page + APA formatted reference(s) The following example provides further insight into what is required for each element of the template. Although the response is intentionally somewhat longer than what is expected, it should help clarify the specific requirements. 1. Ethical Dilemma Prompt objective: Identify the ethical dilemma and state the dilemma as a “should” question. Note: there may be several relevant dilemmas that could be addressed; use the prompt question as a guide to an issue to analyze. The objective is to present a cogent analysis of a relevant issue. ISSUE: Should the attending physician sign a DNR without

- 20. Sally’s consent? 2. Primary issues related to the identified dilemma Prompt objective: Identify the relevant issues related to your dilemma. You should identify at least two, but limit your selection of issues to a manageable number within the scope of the assignment. Informed consent; Surrogate decision making & substituted judgment; healthcare decision making capacity; autonomy and the right to refuse treatment 3. Primary Stakeholders & Stakeholder positions: Question objective: Identify 2-3 primary stakeholders including the patient, and briefly describe their position: Sally: 62 yr old woman with Stage IV breast cancer that is unresponsive to standard and experimental treatment presents with shortness of breath requiring a Thorentisis, a difficult procedure given her condition. Sally wants to live and refuses

- 21. to discuss the terminal nature of her condition. HSC312 - Final Project: Compiled Case Studies May 2013 Jane Doe Sally’s husband: Sally’s husband recognizes that Sally is dying and wants everything done for Sally to make her comfortable. He agrees with the attending physician that CPR would make Sally less, rather than more comfortable. He is Sally’s surrogate decision maker. The attending physician: Believes that further testing and treatment for Sally is futile. He questions whether Sally has the capacity to understand her condition and consent to the DNR. 4. Potential Solution Analysis:

- 22. Prompt objective: Analyze the ethical dilemma from the perspective of the primary stakeholder (typically the patient), using the ethical theories and/or the bioethics principles that relate to the dilemma. Keep your analysis focused on at least two or three moral theories or bioethics principles, but do not attempt to address them all. There will generally be more issues and principles/theories that would apply than you can cover in a short analysis. Include in your discussion any known legal issues presented by the readings that may influence a decision. Apply the facts to the theories discussed. Keep in mind that there may be several issues and theories to discuss, but you are not required to find or address them all. The essay below is purposefully more involved than the assignment requires providing a few

- 23. examples of an ethical analysis. Under the ethical and legal doctrine of informed consent provided by the Patient Self- Determination Act, an adult patient with healthcare decision- making capacity has the right to make an informed, autonomous choice to accept or reject medical treatment. (Munson, 2012). The right to self-determination is defined by the bioethics principle of Autonomy and refers to the patient’s right to make a voluntary choice that is meaningful to them and free from external or personal influences. (Tong, 2007). Such influences may include fear, denial, medication side effects, pain and guilt, among others. Healthcare decision-making capacity requires that the patient can articulate and understand

- 24. the nature of their condition and the risks, benefits and consequences of accepting or rejecting treatment. Assessing decision- making capacity requires an evaluation of the patient’s decision-making process, rather than an evaluation of the choice itself. “…[T]he mere fact that a patient does not accept a health care professional’s recommendation does not necessarily mean that the patient is incompetent" (Tong, 2007, p 53). In order for a patient to evaluate the risks and benefits of an available option is the understanding that a physician will provide complete and honest disclosure of all the associated medical facts that may be pertinent to the patient (Canterbury vs. Spence, 1979). The need for such veracity in

- 25. caring for a patient is also a primary component of a physician’s ethical responsibility, according to the American Medical Association (AMA, 2012). Performing a procedure without consent, or withholding a viable treatment without disclosure, is a direct violation of the AMA mandate, Informed Consent doctrine and a patient’s trust. A patient’s right to self-determination is foundational in bioethics. If the patient loses decision- making capacity, laws and policies are in place to ensure that the patients’ expressed or implied wishes are respected. Prior to losing capacity, a patient can appoint a healthcare proxy agent who will make decisions for the patient, based upon the patient’s wishes and instructions. Critical to

- 26. the concept of a Health Care agent is the agent’s requirement that any decisions reflect the patients’ known and implied wishes, rather than the agent’s own wishes for the patient. If no HSC312 - Final Project: Compiled Case Studies May 2013 Jane Doe such agent is named, a surrogate decision maker is appointed by state statute or facility policy to make decisions for the patient, using their knowledge of the patient and the patient’s wishes, values and spiritual beliefs. Sally appears to be in denial about her condition and terribly afraid of death, as evidenced by her general state of “panic” and her refusal to talk to the Resident

- 27. about her condition. Most importantly, Sally has stated that she wants to live, which may reflect any number of thoughts and emotions from a sense of grief at her circumstances to denial of her terminal condition. Because the physicians seem more focused on discussing their inability to help Sally, rather than being ‘competent’ in her mind to perform the thorientsis, Sally may not see a value in discussing her condition with them. Far from an irrational thought process, Sally’s refusal to talk may actually be a heartbreaking testament to her ability to assess a situation and reach a rational conclusion based on the facts. Further proof may be Sally’s insistence that she “…wanted the emergency squad called to attempt resuscitation if she arrested at home” (Crigger, 1998). Given

- 28. her desire to live as long as possible, it would make sense that she would want every chance available to live. Presuming Sally does have capacity, she is entitled to receive full disclosure regarding anything to do with her medical care—a right that extends to her rejection of a proposal that is in conflict with her own goals. Consequently, if the attending physician institutes a DNR order without Sally’s consent would constitute a violation of Sally’s right to self-determination. Important in the discussion of full disclosure in Sally’s case is the fact that it no one has explained the potential adverse consequences of performing CPR (Cardio- pulmonary resuscitation) on

- 29. someone in her current medical condition. From the facts presented, it is unclear how Sally would respond if she knew there was a significant chance that if she survived CPR, she could end up in a Permanent Vegetative State, permanently unconscious and kept alive by artificial life support as a result. The physician’s position that CPR is futile given the potential for harm and what he perceives as negligible benefit, does not override Sally’s right to define what is and is not beneficial for her. Acting on his own subjective values and interpretations, and ignoring Sally’s values and desires would constitute an act of Paternalism, a direct violation of autonomy (Tong, 2007). While it is true that a patient cannot demand an inappropriate treatment—

- 30. one that would produce more harm than benefit— it could be argued that CPR as a standard emergency procedure to ward off imminent death does not pass the “inappropriateness” test. If a patient with capacity is provided with full disclosure of the potential harms, it is the patient’s right to weigh the risks and benefits, and make an informed choice. (Munson, 2012). Similarly, if it is determined, that Sally lacks capacity; the doctor would still be potentially outside his authority to institute the DNR without informing Sally’s surrogate decision maker. While it is unclear whether Sally’s husband is her Healthcare proxy agent, as a person who knows her best and her spouse, he would still have the presumptive right to use substituted

- 31. judgment and make the decision he believes Sally would make, if she could. Knowing Sally’s express position on the issue of aggressive treatment, he has an obligation as the healthcare agent to reject the DNR, regardless of his personal opinion and desire that Sally just receive comfort care. HSC312 - Final Project: Compiled Case Studies May 2013 Jane Doe In addition to the ethical principle of Autonomy and the doctrine of informed consent, Care- based Ethics also supports Sally’s right to reject the DNR. Care- based Ethics emphasizes values and virtues such as compassion, empathy, kindness and most

- 32. important, sensitivity to each patient’s unique perspective and circumstances (Tong, 2007). Because Sally is adamant she wants everything done right now to help keep her alive as long as possible, a physician empathetic to Sally’s concerns and circumstances would not sign the DNR without at least informing her and addressing her fears about death and her desire to preserve her life. 5. Recommedation: Prompt objective: Present your assessment, resolution or potential solutions for resolving the issue. Remember that there are no right answers, per se, so reflective questions can be as appropriate as a firm conclusion.

- 33. Based on my analysis, the attending physician should not institute the DNR against Sally’s express wishes and without her knowledge. Doing so would violate the ethical and legal principles of autonomy and informed consent. I also recommend that Sally be seen by a Palliative Care specialist or a medical professional trained in end-of-life care to help determine whether Sally’s statements and behaviors demonstrate a lack of capacity, or are understandably motivated by denial and fear. Minimally, the consult should help promote Sally’s overall well- being by addressing her concerns in a compassionate and caring way. Lastly, only if Sally lacks capacity should Sally’s husband, as her healthcare agent, be allowed to speak for Sally and

- 34. refuse the DNR. Because we do not know how Sally feels about remaining on life support should CPR fail, Sally’s husband must adhere to the doctrine of substituted judgement and base a decision upon his knowledge of Sally’s values and wishes, including her known spiritual beliefs. Bibliography 4 H A S T I N G S C E N T E R R E P O R T January- February 2012 To the Editor:The traditional “in- formed consent” process for medical treatment is badly broken. As patients face fateful medical decisions, they of- tendonotknowthebasic“gist”oftheir optionsorthelikelihoodofthepossible

- 35. outcomes, good and bad. The shared decision-makingmovementaimstoim- provethatsorrysituationbyhavingpa- tients and clinicians work more closely together when there is more than one reasonablemedicaloption,asisthecase formanyifnotmostsituations.Byen- suring both that patients are informed about their choices and that clinicians areinformedaboutpatientpreferences, thequalityofmedicaldecisionsshould be improved. Patient decision aids are notthemselvesshareddecision-making; instead, they are tools to help make shareddecision-makingpracticalinthe busyworldofclinicalmedicine. Inhisprovocativearticle(“Question- ing the Quantitative Imperative: Deci- sionAids,Prevention,andtheEthicsof Disclosure,” March-April 2011), Peter Schwartz seems to acknowledge the need to improve the current informed consent process but worries that pro- viding quantitative information about

- 36. possible outcomes as part of a shared decision-makingprocessmightbemis- leadingtoorunwantedbypatients.He proposesthe“default”optionshouldbe to withhold this quantitative informa- tion unless and until a patient asks for it.Hisprimaryargumentsarethatmany patientshavepoornumeracyskillsand might not understand—or might even be misled by—the quantitative facts, andthatoutcomeshavenotbeenshown tobebetterasaresultofprovidingpa- tientswithquantitativeinformation. Problemswithstatisticalnumeracy— which have been shown to be an issue for clinicians, too—do make it more challenging to communicate risks and benefits. However, just because a task is difficult doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be done.MostpeopleintheUnitedStates don’twanttoplayapassiveroleintheir health care, and the proportion isn’t conditioned by assessed numeracy (M.

- 37. Galesic and R. Garcia-Retamero, “Do Low-Numeracy People Avoid Shared DecisionMaking?”Health Psychology30 [2011]:336-41).Moreover,asnotedin PeterUbel’scompanioneditorial(“The Experimental Imperative”), research on the communication of quantitative healthinformationisrevealingthatnew strategies and technologies can help overcome these barriers. For example, visualaids,commonlyusedindecision aids,canhelpevenpeoplewithfewnu- meracy skills better understand health statistics (R. Garcia-Retamero and M. Galesic,“WhoProfitsfromVisualAids? Overcoming Challenges in People’s UnderstandingofRisks,”Social Science Medicine 70 [2010]: 1019-25). Many oftheinterventionsforwhichinformed consentisnecessaryinhealthcare,such as open-heart surgery and organ trans- plantation, had to overcome numerous barrierstoenterthemedicalarmamen- tarium. It’s time to bring a similar in-

- 38. tensityofefforttoovercomethebarriers of literacy and numeracy in communi- catingimportanthealthinformationto thepeoplewhomustlivewiththecon- sequencesoftheirhealthdecisions. Holding informed consent to an outcome standard is an interesting ar- gument. Schwartz acknowledges that decision aids that present quantitative outcomeprobabilitieshavebeenshown to give patients more accurate percep- tionsoftheirhealthrisks.Isputtingthe “informed” in informed consent not an important goal in itself? Would the ethicalandlegalimperativeofinformed consent hold up under scrutiny in a trialwherepatientsfacingsurgerywere randomized to an informed consent process versus none? Would the whole notionofinformedconsentbescrapped iffunctionalstatusscoreswerenodiffer- entinasecondtrial?Ithinknot. Thekeyissuehereiswhetherthede-

- 39. faultoptionininformedconsentshould be withholding quantitative informa- tionunlesspatientsaskforitorprovid- ingitunlesstheysaytheydon’twantit. For too long, the medical system has kept patients largely in the dark about whatclinicianshaveplannedforthem. Given this history, perhaps it’s time to make giving more information—in- cluding quantitative information—the default position, and to work much harderatdoingitwell. Michael J. Barry TheFoundationforInformed MedicalDecisionMaking To the Editor: Every day people tell me about the challenges they face in finding safe, decent health care and making the most of it. Facing tough letters

- 40. TooMuchInformation? It’s time to overcome the barriers of literacy and numeracy in communicating important health information to the people who must live with the consequences of their health decisions. DOI:10.1002/HAST.4 January-February 2012 H A S T I N G S C E N T E R R E P O R T 5 oN tHe WeB nBioethicsforum http://www.bioethicsforum.org AdministrationRevealsLackofCLASS By Peter S. Arno, Michael K. Gusmano, and Deborah Viola

- 41. Just as the baby boomers are entering retirement, the first real step toward a national long-term care policy in forty-five years has been cast asunder. WhatisHumane?APleaforPlain LanguageintheDebatesonAnimal Experimentation By Joel Marks “Humane” is implicitly defined as meeting accepted standards of care and use according to legal and institutional guidelines. What this means in practice is that anything can be done to a laboratory animal, provided it is necessary to carry out an experiment or other procedure that a committee has deemed worthy on scientific and perhaps humanitarian grounds. I submit that this is an illegitimate use of the term “humane.” Also:michaelK.Gusmanopointsout misinformationaboutU.S.poverty; CarolLevinesuggeststhatwe’dallbetter startsavingnowforourbabies’future

- 42. long-termcare;franklinG.millerand robertd.truogexploreuncertain- tiespromptedbythelatestresearch onpatientsinthevegetativestate;and CameronWaldmanvisitsZuccottiPark totalkwithcliniciansoccupyingWall Street. nthehealthCareCostmonitor http://healthcarecostmonitor. thehastingscenter.org GlobalCompetitiveness:HowOther CountriesWin By Daniel Callahan and Elizabeth H. Bradley Nearly every country that leads the world in international economic competitive- ness also has a strong government-run or regulated universal health care system and a comprehensive welfare policy. The one exception is the United States. decisions about treatments and tests withlittleornoobjectiveinformation

- 43. toguidethemoftentopstheirlistofdif- ficulties.Ihavefrequentlyexperienced thismyselfasIrecoverfromtreatment ofmyfourthcancerdiagnosis. I appreciate Peter Schwartz’s recog- nitionoftheburdenplacedonpatients andlovedonestoincorporatecomplex risk information into decisions about our care. And I welcome any con- cern—however tangential—about the shiftofresponsibilitiesfromclinicians to patients, who are often ill-prepared tofulfillthem.However,Ifindhisar- gumentoverlyprotectiveinlightofthe rushed, confusing demands of health care today, increased public access to health information, and the shared decision-making policies imbedded in theAffordableCareAct. Schwartzdescribesthegeneralinnu- meracyoftheAmericanpublicwitha particularemphasisonourinabilityto understandthedifferencebetweenrel-

- 44. ativeandabsoluterisk.Yetheneglects to mention that we share this deficit with many of our clinicians. He also summarizestheliteratureoncognitive heuristicsbutagainexemptsclinicians from discussion. Does he believe that cliniciansareimmunefromthesesame biases? My doctor might withhold a decision aid because she doesn’t have timeforthiscumbersomeshareddeci- sion-making nonsense or she believes sheknowswhatIshoulddotorealize thebestoutcome.Shewouldvieweach oftheseasrationalchoices. More puzzling is the importance Schwartz assigns to risk information indecisionswemakeaboutourhealth care, preference-sensitive or not. Em- piricalinformationisalways only oneof manyfactorsthatinfluenceourchoic- es. Scant relevant risk information is available for most of the health care decisionswemakenow.Wejustwing it, based on anxiety, our neighbor’s

- 45. experience, and our sense of what the rightchoiceistoday,whichcanbein- fluencedbyourdoctor’smoodaseasily asitcanbyfamilyandworkevents. It is thus oddly shortsighted for Schwartz to recommend withholding decision aids for some patients (based on the clinician’s assessment of our competence) in the relatively few in- stances where these aids are available forpreference-sensitivecare,astheyare for decisions about early-stage breast cancertreatmentorgettingaprostate- specific antigen test. Even if we don’t fully understand what’s at stake, well- presented risk information powerfully communicates that we have choices: that multiple treatment options are possible,thattherearetrade-offstobe considered,andthatnoguaranteesex- ist,regardlessofourchoice.Theseare sobering but important messages for ustograspaswe,regardlessofournu-

- 46. meracy skills and cognitive biases, are routinely forced to make critical deci- sionsaboutourhealthcare. It’s too late to argue that our clini- cians should selectively provide de- cision aids: the ACA provisions for shared decision-making will likely eventuallytieclinicianreimbursement toprovidingthem.Andtheimpetusfor thatargument—thatprovidingthisin- formationimposesmandatoryautono- my—isakintodiscussingthebenefits ofclosingthebarndoorafterthecows havewanderedaway:Ourautonomyis alreadymandatedbydefault. Jessie Gruman CenterforAdvancingHealth To the Editor: In his article, Peter Schwartzeloquentlydiscussestheben- efits and potential harms of providing patients with numeric risk informa- tion. He describes how—despite our

- 47. best efforts to inform patients about therisksandbenefitsofscreeningtests and preventive treatments and to im- prove understanding of probability— people “have persistently irrational responses to quantitative information aboutrisksandbenefits,”regardlessof their level of numeracy. For decades, 6 H A S T I N G S C E N T E R R E P O R T January- February 2012 decision scientists, economists, and psychologists have struggled to under- standwhyeventhemostknowledgeable andnumeratepeoplemakesuboptimal healthdecisions. It seems that in our attempts to educate patients about probability, we sometimes fail to appreciate that un- derstanding numeric facts and figures is not an exclusively cognitive effort;

- 48. rather, it is often heavily influenced by affect, which in turn influences one’s abilitytoreason.Awell-knownexperi- ment conducted in 1994 by Veronika Denes-Raj and Seymour Epstein illus- trates how affect can trump rational- ity, even for well-educated people. In it,subjectswoniftheydrewaredjelly beanfromoneoftwobowls.Thesmall bowlcontainedoneredandninewhite beans,andthelargebowlcontainedfive totenredbeansandatotalofonehun- dred beans in all. Despite the fact that eachbowlwaslabeledwiththepercent of red beans it contained, the majority of subjects drew a bean from the large bowl, which was clearly the inferior choice.Subjectsreportedthatthey“felt” theyhadabetterchanceofwinningby selectingthebowlwiththegreaterabso- lutenumberof“winning”beans. Theinteractionofaffectandnumer- acy in health decisions has been dem- onstrated in several studies examining

- 49. choices of medical treatments that in- cludepotentialsideeffects.Inone2006 studyconductedbyJenniferAmsterlaw and colleagues, people were presented with two surgical scenarios: one had a 20percentmortalityrate,andtheother had a 16 percent mortality rate along witha1percentchanceoffourunpleas- ant side effects (colostomy, chronic di- arrhea, intermittent bowel obstruction, orwoundinfection).Mostpeoplechose thesurgicaloptionwiththehighermor- tality,presumablybecauseoftheiraffec- tiveresponsetothesideeffectsandtheir tendencytooverweightlowprobability events. Indeed, the mere presence of a small side effect may decrease willing- ness to undergo treatment, even if the treatment offers substantial benefit. Erika Waters and colleagues found in 2007 that side-effect aversion occurred regardless of how probability was pre- sentedorwhethergraphicformatswere used to convey risk information, sug-

- 50. gestingthatdecisionswereguidedbyan affective response to the possibility of sideeffects,ratherthanbynumericrisk. There are, of course, potential dan- gers associated with providing patients with too much quantitative informa- tion.Inthiseraofshareddecision-mak- ingandunprecedentedaccesstohealth information, it is easy to experience dataoverload.Providingpeoplewithall available information can actually hin- derdecision-making,andoften,lessnu- mericinformationismorewhenhelping people make quality health decisions. Amongthepotentialdangersofprovid- ing too much information is that pa- tientsmaynotbeabletodiscernuseful informationfromthemerelyrelevantor altogetherirrelevant.However,thereare also potential dangers associated with providingtoolittleinformation.AsAn- thonyBastardiandEldarShafirdemon- stratedin1998,whenpeoplearefaced

- 51. with a preference-sensitive decision, they often seek additional information regardless of whether that information iscriticaltotheirdecision.Inaseriesof experiments,theyobservedthatpeople whopursuedmissinginformationtend- ed to endow it with greater value than theywouldhaveifithadbeenavailable initially. Somehow the act of pursuing a missing but nonessential piece of in- formation lent greater psychological weight and salience to it. In a health context, such misguided information- seekingmightleadpatientstobaseim- portanthealthdecisionsonfactorsthat may be relevant but nonessential to an effective decision. Clearly, more work is needed to understand the possible unintended consequences of providing toomuchortoolittleriskinformation. Attheveryleast,providersshouldkeep in mind how affect can be attached to numbersandrisksareperceived.

- 52. Wendy Nelson NationalCancerInstitute To the Editor:Thereisagreatdeal of merit in Peter Schwartz’s important andusefularticle,anditwilldoubtless prompt considerable debate. I would liketoaddtwobriefcomments. First, Schwartz’s target—the quan- titative imperative—can be viewed as a specific instance of a broader target. In Rethinking Informed Consent (Cam- bridge University Press, 2007), Onora O’Neill and I, like Schwartz, were struckbytheconsiderableevidencethat patients and research subjects often do not comprehend what is disclosed. As a result, “informed consent” is often considered obtained even when, rela- tive to contemporary standards, it is substandardorinvalid.Toimprovethis situation, we argued—amongst other things—thatweneedtobeclearabout

- 53. the distinction between consent and informed consent. The former is a fa- miliar form of action that involves the settingasideofrightsortheremovalof certain kinds of prohibitions. Consent isofconsiderable,butnotfoundational, ethical importance for clinical actions. Whilethosewhoconsentneedtoknow something of the action to which they consent,itdoesnotrequire“disclosure” of large amounts of information about proposed actions or risks. Informed consent, in contrast, has its roots in negligence law in the clinical context andsharesbiomedicalethics’particular The quantitative imperative is simply part of an unjustified informative imperative that places unfeasible demands upon those consenting. January-February 2012 H A S T I N G S C E N T E R R E P O

- 54. R T 7 focus on the importance of individual decision-making. We argued that bio- medical ethics has, without sufficient justification,takeninformedconsentto be of key ethical importance. Matters are made worse by the prevalence of a widerangeofmetaphorsthatshapeour thinkingaboutknowledgeandcommu- nication,suchthatinformationisread- ilycastasatypeof“stuff ”tobepassed on,stored,disclosed,orpickedup. Putting these elements together and aligning with Schwartz’s terminology, there is a ubiquitous informative im- perative that pervades biomedical eth- ics. This informative imperative rests uponarangeofdistortionsandconfu- sions. Once the ethical arguments are clarified, the informative imperative canbeseenasmuchlessdemandingin its scope than is typically assumed.We would thus agree with Schwartz’s con-

- 55. clusion—that quantitative information ofcertainkindsneednotbedisclosed— but for a different set of reasons. The quantitativeimperative,onourview,is simplyapartofawidespreadbutunjus- tifiedinformativeimperativethatistoo broadinitsscopeandplacesunfeasible demandsuponthoseconsenting. Second, it is important to note that there may be reasons other than en- suring validity of consent for disclos- ing quantitative information. Given the legal context of informed consent, Schwartz’s proposals might raise wor- riesforclinicians.Supposeinformation aboutcertainrisksismerelymadeavail- able, rather than being communicated (andacknowledgedassuchby,say,sign- ingaconsentform).Supposethatoneof therisksnotcommunicated,butmade available,happens.Thepatientsueson thebasisthathadshebeeninformedof therisk,shewouldnothaveconsented. Thequantitativeimperativecanthusbe

- 56. seenasaprecautionarystrategyforcli- niciansandtheirinstitutions. Schwartzfocusesontherolethatin- formationplays,orispurportedtoplay, inenablingpatientdecision-making.In arecentpaperintheJournal of Medical Ethics (“Why Do Patients Want Infor- mation If Not to Take Part in Deci- sion Making?”), I focus on the (good) reasons that patients have for wanting information other than for decision- making purposes. Patients want infor- mation because they expect it, because it allows them to establish trustworthi- ness and credibility with their doctor, and because the very process of com- municatinginformationcanbeasignal of respect and faith in a patient’s com- petence. So even if we agree that the quantitative imperative lacks firm ethi- cal support, we might still believe that suchinformationshouldbedisclosed.

- 57. Neil C. Manson LancasterUniversity Peter Schwartz replies: I must correct Jessie Gruman’s sug- gestion that my article supports with- holdingdecisionaidsorquestionstheir importance. Like Michael Barry and Gruman, I agree that patients often want or need more information than theyreceive,andIbelievethatdecision aidscanhelpaddressthisproblemand will most likely play a growing role in medicine. But the question is whether decision aids can best help patients by always providing quantitative infor- mation—in particular, complex data framedinmultipleways,astheInterna- tional Patient Decision Aids Standards andmanyexpertsrecommend. Research has not established that such disclosure improves patients’ un- derstanding or decision-making in the

- 58. range of situations where decision aids mightbeused.Therearemanypossible negative impacts, mostly stemming frominnumeracyandheuristicsandbi- asesinhumanthought,asdescribedin myarticleandintheexcellentaddition- alexamplesprovidedbyWendyNelson inherletter.Givenallthis,Iarguethat the quantitative imperative must be subjectedtomorecarefultesting,inthe spiritofevidence-basedmedicine. Barry’sletterandPeterUbel’seditori- althataccompaniedthearticlesupport research to investigate innovative ways to provide quantitative information to inform patients, including innumer- ateones,withoutcreatingconfusionor engendering irrational responses. Such researchiscertainlyimportant,butmy article emphasizes that the question is not just how to present certain types of data, but whether to present data at all, and in what situations. Researchers

- 59. shouldnotassumethatallrelevantdata shouldbegivenallthetime:itmayturn out that in at least some cases, less is more (for example, see B.J. Zikmund- Fisher, A. Fagerlin, and P.A. Ubel, “A Demonstration of ‘Less Can Be More’ in Risk Graphics,” Medical Decision Making30[2010]:661-71). My article is thus a call to keep an open mind as research goes forward. It aimstoplayarolethattheoreticalethi- cal and philosophical analysis should play:identifyingandcritiquingassump- tions that guide behavior or research in unrecognized or unexamined ways. The assumption that all quantitative information should be provided all the timeisexactlythatsortofphilosophical commitment. I agree with Gruman that patients too often cannot get information they want, but I believe that decisions aids maybestaddressthatproblembymak-

- 60. ing the information available to those who want it, rather than presenting it to everybody. She raises the excel- lent question of how to choose who will receive additional data, and she is right, of course, to reject the idea that thedecisionshouldbebasedsimplyon a clinician’s impression of the patient’s competence. But what about a system where pa- tientsareofferedadditionalinformation Letterstotheeditormaybesentbye-mail to [email protected], or to Managing Editor, Hastings Center Report, 21MalcolmGordonRoad,Garrison,NY 10524; (845) 424-4931 fax. Letters ap- pearing in the Report may be edited for lengthandstylisticconsistency. 8 H A S T I N G S C E N T E R R E P O R T January- February 2012

- 61. of various sorts? This idea is far from radical: recommendations for discus- sionsbetweenhealthcareprovidersand patients suggest that some information shouldbegiveninitially,andadditional informationshouldbeofferedasanop- tiontothosewhowantit(see,forexam- ple,R.M.Epstein,B.S.Alper,andT.E. Quill, “Communicating Evidence for Participatory Decision Making,” Jour- nal of the American Medical Association 291 [2004]: 2359-66). The amazing capabilitiesofcomputer-baseddecision aidsmaytemptdesignerstoprovidetoo muchinformationupfront,andtofor- getthewisdomoftailoringdisclosureto thepatient’sinterestandunderstanding. I agree with Neil Manson that the quantitative imperative is part of a larger “informative imperative” in medicine that should be questioned and challenged as Manson, O’Neill, Carl Schneider, and others have done.

- 62. Considering how to provide the right information,totherightpatients,atthe right time, by way of a decision aid or personal interaction, raises important ethical and empirical questions, as the articleemphasizes. Doctors and Torture To the Editor:In“TheTorturedPa- tient: A Medical Dilemma” (May-June 2011), Chiara Lepora and Joseph Mil- lum raise the issue of whether a physi- cian may be justifiably complicit in torture and answer in the affirmative. Their argument is predicated on there being a litany of moral considerations, of which the wrongness of complicity in torture is merely one; this wrong- ness competes against other values and sometimes is outweighed. While I disagree with some of the authors’ as- sumptions—for instance, that torture is always unethical in the cases that physicians are forced to countenance,

- 63. orthatcomplicityinanimmoralactis primafacieimmoral—Iagreewiththeir conclusion. Surely those who trumpet deontological constraints would think otherwise,butthisconclusionnaturally follows from a pluralistic set of moral values. Whiletheyciteawiderangeofdec- lamations against physicians’ involve- mentintorture,onethattheyleaveout comesfromsection2.067oftheAmeri- canMedicalAssociation’sCode of Medi- cal Ethics. What makes section 2.067 interesting is not just what it says, but alsothefactthatitcomeshierarchically nestedundersection2.06,whichspeaks tophysicianinvolvementincapitalpun- ishment. From the Code’s perspective, the issues pertaining to capital punish- mentandtortureareisomorphic:what mattersismerelythatphysicianinvolve- mentcouldmakethepatientworseoff. In the case of capital punishment, the

- 64. upshotisobviousand,inthecaseoftor- ture, resuscitation in order to facilitate moretortureissimilarlydepraved. This argument fails in both cases, andthereasonhelpselucidatewhyLe- poraandMillumareontherighttrack. Thequestiontoaskislesswhatwould happen if physicians were present, but rather what would happen if they were not. For example, imagine that physicians were disallowed from these settingsandaprospectivepatientexpe- rienced complications: the abolitionist would just settle for this person being worseoff.Aphysician’spresenceensures thateasilyremediablesituationsberem- edied, which is precisely what I would advocate.Thisisnottosaythatthereare nocapacitiesinwhichphysicianscould make people worse off, just that there are some in which those people could be made better off; therefore, a whole- saleabolitiononphysicianparticipation misses the mark. (There’s also an open

- 65. question about whether such agents should be conceived of as “physicians” atall—asopposedtomedicallytrained militarypersonnel—butIshallnotpur- suethatdiscussionhere.) Tobesure,thoseopposingphysician involvement in either capital punish- mentortortureare,almostalways,not just opposing physician involvement, but rather those practices themselves. When the Code says that physicians must “oppose . . . torture for any rea- son,” it is clearly making a political claim and not one narrowly tied to medicalethics;itisforpreciselythisrea- son that I find such statements by the Codetobeinappropriate.AsLeporaand Millum acknowledge, some debate the appropriateness of torture in “narrowly specified, extreme cases.” It is a credit to their essay that such a debate is left open,ratherthanforeclosedbyfiat.

- 66. Fromtheperspectiveofmedicaleth- ics,thecentralquestioniswhetherphy- sicianinvolvementintorturemakesthe patientbetterorworseoff.Fromamore thoroughgoingconsequentialismofthe sort that I would advocate, this ques- tion bears no privileged status. While Lepora and Millum would surely not agreewithallofmyarguments,theyare tobecommendedforeschewingdogma andreachingacontroversialconclusion. More generally, one would also hope that their paper portends increased at- tention to military medical ethics; this is an important area within medical ethics,andonethathasreceivedinsuf- ficientattention. Fritz Allhoff WesternMichiganUniversity The question to ask is less what would happen if physicians were present, but rather what would

- 67. happen if they were not. Copyright of Hastings Center Report is the property of Wiley- Blackwell and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use. 10/27/2016 Final Case Analysis: The Emilly Dilemma - Abortion https://mycourses.excelsior.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-3200850-dt-co ntent-rid-31405097_1/courses/BHS.HSC312.Online.201610.201 612.s30047605/course%20wide… 1/3

- 68. Final Case Analysis: The Emily Dilemma - Abortion Introduction to the Activity Recall, that an ethical dilemma can be defined as two morally a cceptable choices, both of which will result in morally disturbing and unwelcome conseque nces. Often when we considering our position regarding an ethical dilemma, it is help ful to consider not only the issue presented, but whether we can justify our position based o n an extreme, yet realistic set of conditions. Abortion is perhaps one of the most disturbing and confounding of issues for engaging in such an exercise, as it is sometimes difficult to j ustify the inconsistencies in our moral intuitions when confronted with situations that define an ethical dilemma. Related Reading from Module 7: Module notes and assigned textbook pages Videos: Ankele, J. (Producer), & Macsoud, A. (Producer) (2010). Beyon

- 69. d the politics of life and choice: A new conversation about abortion (link availab le in Mod 7) Tsiaras, A. (Director) (2011, November 14). Alexander Tsiaras: Conception to birth -- visualized TedTalks. [Video file][9 min 37 sec]. Retriev ed from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fKyljukBE70 (apprx. 10min) Iadarola , J. (Performer) (2012, November 25). Study: What hap pens to women denied abortions? [Video file][5 min 17 sec] The Young Turks. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dWBjQ7P9SSs (apprx. 5 min ) Instructions to Learners Please read the case scenario: Twenty year old Emily who suffers from Bi-polar disorder and Schizophrenia lives at home with her parents, but is fairly independent. Last year, Emily had a breakdown while living away at school and required hospitalization. Due to a complex mix of anti-psychotics,

- 70. antidepressants and other medications to control her condition, Emily is now working part- time at a local bookstore and taking two classes at the communit y college. Emily loves children and hopes eventually to become a kindergarten teacher. Although Emily is on birth control pills, she had missed some days over the past few months during a brief ‘lapse’ in her mood, but insisted throughout that time that her b oyfriend wear a condom. The condom failed at some point and Emily is now eight weeks' pregnant. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fKyljukBE70 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dWBjQ7P9SSs 10/27/2016 Final Case Analysis: The Emilly Dilemma - Abortion https://mycourses.excelsior.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-3200850-dt-co ntent-rid-31405097_1/courses/BHS.HSC312.Online.201610.201 612.s30047605/course%20wide… 2/3 Emily’s doctors insist that the baby is at an exceptionally high r

- 71. isk for severe physical and mental impairments, including incomplete limb and/or brain dev elopment. At best, there is no solid data detailing teratogenicity risk for all of her medicati ons, but the combinations and inability to incorporate less harmful substitutes raise signifi cant concern. Because she is within the first trimester, there are no legal concerns based on the Roe v. Wade decision so the doctors, her parents and her boyfriend are insisting that E mily have an abortion to spare the burden on the child. Emily, a devote Catholic, insists on carrying the baby and raising it once it is born. She has also personalized the argumen ts, finding that by devaluing the life of her baby, her family and others devalue her as well. Emily’s parents have threatened to file for guardianship over he r so that they can force the abortion, under their belief that she lacks decision-making capa city and the abortion is in her best interests. Although the doctors have no standing to join the suit, they have agreed to serve as expert witnesses for the parents. Emily’s boyfriend i s considering petitioning

- 72. the court--after the baby is born--for the right to be released fro m any parental responsibilities, given his lack of a position in the decision to a bort. Emily’s Psychiatrist, Dr. Heady is very troubled by the case bot h for Emily and for the developing fetus. Knowing that you are a famous ethicist, he co ntacts you informally and presents the case as a hypothetical, maintaining Emily’s confide ntiality. Dr. Heady is unsure whether the parents can legally force the abortion, but he is troubled on a much more fundamental level, which is why he is seeking your counse l. Please respond to the following questions (approx. 500-700 wor ds) using the template format provided for the assignment: Presuming that Emily has decision-making capacity, Dr. Heady would like to hear your thoughts on the following: Ethically, should Emily be able to reject the abortion in the first

- 73. trimester, knowing that it is highly probable that continuing to take her necessary medications will severely and permanently impair the baby? In reflecting upon the question, recall the court’s arguments in Roe v. Wade, and any counter arguments provided in your materials. Also, consider th e question of the fetus (encompassing all stages from conception through prebirth development) and the concept of moral standing. Use the following template for your assignment: 1. Use Microsoft Word to create a document. 2. Copy/paste the title of the question. 3. Describe the most relevant ethical dilemma(s) presented (no more than two). 10/27/2016 Final Case Analysis: The Emilly Dilemma - Abortion https://mycourses.excelsior.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-3200850-dt-co

- 74. ntent-rid-31405097_1/courses/BHS.HSC312.Online.201610.201 612.s30047605/course%20wide… 3/3 4. Briefly describe the primary issue or issues that are relevant i n the scenario with respect to the dilemma. 5. Identify the most relevant stakeholder(s) (no more than 3) an d briefly describe the situation from their perspective. 6. Analyze the dilemma, using scholarly discussion, from the pe rspective of the primary stakeholder (typically the patient). Include a discussion of at lea st two ethical theories or bioethics principles studied in the course that relate to the dil emma and issues you identified. Include any relevant legal concerns or requirements outlined in the readings. 7. Present your assessment, resolution or potential solutions for resolving the issue. Remember that there are no right answers, per se, so reflective q uestions can be as

- 75. appropriate as a firm conclusion. 8. Title page + APA formatted reference(s). 10/27/2016 Final Case Analysis: Paternalism vs Autonomy https://mycourses.excelsior.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-3200850-dt-co ntent-rid-31405097_1/courses/BHS.HSC312.Online.201610.201 612.s30047605/course%20wide… 1/2 Final Case Analysis: Paternalism v.s. Autonomy – Dax Cowart Introduction to the Activity I would like to introduce you to the story of Dax Cowart. Attach ed is an excerpt from a speech that Dax Cowart made several years ago, a speech that re mains poignant for contemporary reflection. The story is heart breaking and challen ges all the bounds of ethics and health care. As you listen to Dax, or read the transcri pt of his talk, think about

- 76. the issues Dax discusses, especially in connection with capacity and the right to decline medical treatment (which we will discuss in greater detail later on in the course). These are the stories and circumstances where ethics and health care colli de and individuals are forced to make tough decisions. In thinking over your responses to the Discussion Board questions, consider the concepts we have talked about in this M odule and in Module I, such as personal moral values; bioethical principles; the need to weigh and prioritize competing moral interests; a physician’s charge to provide ethic al care and a patient’s right to self-determination. Related Reading from Module 2: Munson text: pp. 36; 38-40 (end at State Paternalism); 41-42 (e nd at Informed Consent); 891904; UVA News Makers - Dax Cowart (Note: you may either watch the video part 1 [Video file] [09 mi n 30 sec], and

- 77. video part 2 [Video file] [07 min 53 sec] or read the transcript a nd Hastings Center Report: Confronting Death: who chooses, who controls?) Instructions to Learners Please respond to the following questions (approx. 500-700 wor ds) using the template format provided for the assignment: You are Dax’s physician. How would you respond to Dax’s requ ests that you “let him die”? Would you continue to treat him against his wishes? Why or Wh y Not? Use the following template for your assignment: 1. Use Microsoft Word to create a document. 2. Copy/paste the title of the question. 3. Describe the most relevant ethical dilemma(s) presented (no more than two). 4. Briefly describe the primary issue or issues that are relevant i n the scenario with respect to the dilemma.

- 78. http://www.virginia.edu/uvanewsmakers/newsmakers/cowart.ht ml https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSsu6HkguV8&list=PLD93B CDA6AFE8C393 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oGISGeKqCEM http://www.virginia.edu/uvanewsmakers/newsmakers/cowart.ht ml http://vlib.excelsior.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/l ogin.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=1998034028&site=ehost- live&scope=site 10/27/2016 Final Case Analysis: Paternalism vs Autonomy https://mycourses.excelsior.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-3200850-dt-co ntent-rid-31405097_1/courses/BHS.HSC312.Online.201610.201 612.s30047605/course%20wide… 2/2 5. Identify the most relevant stakeholder(s) (no more than 3) an d briefly describe the situation from their perspective. 6. Analyze the dilemma, using scholarly discussion, from the pe rspective of the primary stakeholder (typically the patient). Include a discussion of at lea

- 79. st two ethical theories or bioethics principles studied in the course that relate to the dil emma and issues you identified. Include any relevant legal concerns or requirements outlined in the readings. 7. Present your assessment, resolution or potential solutions for resolving the issue. Remember that there are no right answers, per se, so reflective q uestions can be as appropriate as a firm conclusion. 8. Title page + APA formatted reference(s). 10/27/2016 Final Case Analysis: Morally Wrong or Ethically Challenging? https://mycourses.excelsior.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-3200850-dt-co ntent-rid-31405097_1/courses/BHS.HSC312.Online.201610.201 612.s30047605/course%20wide… 1/2

- 80. Final Case Analysis: Morally Wrong or Ethically Challenging? Introduction to the Activity Many states have considered enacting PAS legislation since Ore gon first legalized the practice in 1994, but as of yet, only Oregon and Washington have laws allowing for Physician Assist ed Suicide (PAS) 127.800; RCW 70.245). In Montana, although there is no current legislation regarding PAS, the Mont ana Supreme Court provided protection for doctor’s providing lethal medication to terminally ill patient’s upon requ est (Baxter v. Montana, 2009 MT 449). Currently, forty-three states have specific laws (either statutory or common law (case law) prohibiting assisted suicides, but four states (Hawaii, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming) and the District of Columbia have no l aw regarding the subject. Just recently, Massachusetts voters defeated a ballet initiative based upon the Oregon statute by a marginal 51% majority. Related Reading from Module 5: Module notes and assigned textbook pages Arras, J. (1997). Physician-assisted suicide: a tragic view. The J ournal Of Contemporary Health Law And Policy, 13(2), 361-389. (28)

- 81. *The New York State Task Force on Life and the Law, (1997). When death is sought assisted suicide and euthanasia in the medical context supplement to report. Retrieve d from website: http://wings.buffalo.edu/bioethics/suppl.html. *Scroll down and read until the end of the passage “IV The Dist inction Between Administering High Doses of Opioids to Relieve Pain and “Physicianassisted Death.” Public Health, (1997). Oregon revised statute: Death with dignit y act (Chapter 127). Retrieved from Oregon Health Authority website: http://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/Evalu ationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Pages/ors. rules: 127.800 s.1.01. Definitions - 127.875 s.3.13. Insurance or annuity policies. Dep’t of Public Health, Annual Report on Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act (2012) [PDF file size 197 KB] http://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/Evalu ationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year15.pdf *Scan through the report to get an idea on how the statistics are compiled and trends recorded Instructions to Learners

- 82. Please read the case scenario: You are a physician-ethicist at Hope hospital in Nirvana, USA. Your state is voting this month whether to allow PAS, under the exact guidelines and safeguards instituted in Oregon. The lo cal news station has asked you to join a televised multi- disciplinary panel and discuss the following questions: Reviewing the safeguards included in the Oregon Statute, which one(s ) potentially raise the most concerns in terms of their ability to protect patients in Nirvana, USA? In developing your response, consider whether the concerns are morally founded or policy oriented. Also keep in mind the rules of profe ssional responsibility, patient rights and the principles of bioethics we have studied throughout the course. NOTE: Please use the modified template below when considerin g your response with respect to completing the template, remember that a stakeholder can be described as many entities, such as but not limited to an individual, a professional society, the public at large or a subset of the population. Modified Template: 1. Use Microsoft Word to create a document

- 83. 2. Copy/paste the title of the question 3. State the safeguards that you find most concerning. 4. Identify the most relevant stakeholder(s) (no more than 3) pot entially affected by the safeguards you listed. http://www.lexisnexis.com.vlib.excelsior.edu/lnacui2api/api/ver sion1/getDocCui?lni=3S3T-V110-00CV- P0S8&csi=138724&hl=t&hv=t&hnsd=f&hns=t&hgn=t&oc=0024 0&perma=true http://wings.buffalo.edu/bioethics/suppl.html http://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/Evalu ationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Pages/ors.aspx http://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/Evalu ationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year15.pdf 10/27/2016 Final Case Analysis: Morally Wrong or Ethically Challenging? https://mycourses.excelsior.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-3200850-dt-co ntent-rid-31405097_1/courses/BHS.HSC312.Online.201610.201 612.s30047605/course%20wide… 2/2 5. Analyze the concerns, using scholarly discussion from the per spective of the primary stakeholder. Include a

- 84. discussion of at least two ethical theories or bioethics principles studied in the course that relate to the dilemma and issues you identified. Include any relevant legal concerns or req uirements outlined in the readings. 6. Present your assessment, resolution or potential solutions for resolving the concern. Remember that there are no right answers, per se, so reflective questions can be as appropria te as a firm conclusion. 7. Title page + APA formatted reference(s) 10/27/2016 Final Case Analysis: Confidentiality, Disclosure and Livid Love birds https://mycourses.excelsior.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-3200850-dt-co ntent-rid-31405097_1/courses/BHS.HSC312.Online.201610.201 612.s30047605/course%20wide… 1/3 Final Case Analysis: Confidentiality, Disclosure and Livid Love birds

- 85. Informed consent requires not only that a patient receive all of t he information necessary to make a reasoned decision, but also that they are able to process and understand the information provided. Language or cultural differences may imp ede understanding, and a blanket reliance on a doctor’s judgment may subvert the intent o f the disclosure. Other barriers to informed consent, such as denial, fear and even famil y dynamics are often more difficult to spot, but equally if not more detrimental. Relat ionships between patients, family members and healthcare providers often morph over time into roles and role reversals that present special challenges in healthcare ethics and the doctor-patient relationship. In this activity, you will consider the standards of professional responsibility, medical ethics and the doctor-patient relationship as they apply when the boundaries between the roles become blurred. Related Reading from Module 3:

- 86. Module Notes Munson text: (end at Parents & Children). AMA Opinion 10.01 - Fundamental Elements of the Patient-Phy sician Relationship Mitnick, S., Leffler, C., & Hood, V. (2010). Family caregivers, patients and physicians: ethical guidance to optimize relationships. Journal Of General I nternal Medicine, 25(3), 255-260. Principles of Medical Ethics. (2001). Schwartz, P. H. (2011). Questioning the Quantitative Imperative : Decision Aids, Prevention, and the Ethics of Disclosure. The Hastings Center R eport, (2), 30. doi:10.2307/41059016 Instructions to Learners Please read the case scenario: Mr. and Mrs. Lovebird were approaching their 65th wedding an niversary when it was discovered that Mr. Lovebird was battling Stage IV lung cancer, with metastasis to his colon. Vowing to “Fight this thing!” the Lovebirds sought out th

- 87. e best specialists and Mr. Lovebird underwent two surgeries, chemotherapy and several ro unds of radiation. Mr. Lovebird did quite well for a while, but lately he has experience d severe fatigue and discomfort. He has also lost his appetite, resulting in a 15lb wei ght loss in just two months. Concerned, the Lovebirds went to see Dr. Friendly, their primar y care physician for over 30 years, whom they trust implicitly. Knowing that the Lovebirds a re in denial to some extent, but also believing that medicine is an inexact science, Dr. Frien dly told them both about an http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical- ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion1001.page http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical- ethics/code-medical-ethics/principles-medical-ethics.page http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.vlib.excelsior.edu/eds/detail?vid=2& sid=3a5595c1-f673-4a7c-9b34- ff2409ff1a33%40sessionmgr4001&hid=4105&bdata=JnNpdGU9 ZWRzLWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#db=rzh&AN=201 1703087

- 88. 10/27/2016 Final Case Analysis: Confidentiality, Disclosure and Livid Love birds https://mycourses.excelsior.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-3200850-dt-co ntent-rid-31405097_1/courses/BHS.HSC312.Online.201610.201 612.s30047605/course%20wide… 2/3 experimental treatment option that might be worth “checking int o,” even though the chances were slim that it would provide much benefit. At a dinner party for a mutual acquaintance, Dr. Friendly is app roached by Lancelot, the Lovebird’s only child. Dr. Friendly is aware of the close relatio nship between Lancelot and the Lovebirds, so he is concerned for their welfare when Lancel ot approaches him. Once alone, Lancelot appears upset and tells Dr. Friendly that he is co ncerned about the experimental treatment option Dr. Friendly mentioned to the Lo vebirds, given Mr. Lovebird’s fatigue and weight loss. From Lancelot’s perspective , it is obvious that even if successful, it would only buy Mr. Lovebird a few months and th

- 89. ose months may not be very good ones. He is also concerned that Mr. Lovebird is tired of treatments, but goes along to please Mrs. Lovebird. Dr. Friendly smiles and shakes h is head “Your mother has always been a force to be reckoned with,” he says “But, in realit y, a few months is better than no months!” He also assures Lancelot that if the Oncologis t does not think Mr. Lovebird is a good candidate for the procedure, the Oncologist will tell them so. When Lancelot suggests that Dr. Friendly’s professional judgme nt may be colored by the Lovebird’s denial, Dr. Friendly becomes defensive, stating that as their doctor all he can do is provide them with information and statistics on the disease pr ognosis and the benefits and risks of any potential options. He admonishes Lancelot, stat ing “if your parents want to believe in miracles, I am not going to take that away from them, and you shouldn’t either!” Visibly upset, Lancelot insists that Dr. Friendly discuss the Hos pice option with the Lovebirds, preferably with Mr. Lovebird, first. Although Dr. Fri

- 90. endly is concerned that the idea of Hospice could be more lethal to the Lovebirds than any experimental treatment, he agrees, on the condition that Lancelot raise it with the Lovebird s first. “If your parents seem open to the conversation, give me a call or have them call me, a nd I will sit down with them to discuss the options.” The next day, Lancelot goes to see Mr. and Mrs. Lovebird, and s hares his conversation with Dr. Friendly, telling them that both he and Dr. Friendly agr ee that it may be time for Hospice services. Both the Lovebirds become very angry that he was discussing them with Dr. Friendly without them knowing it. They are also devastated that Dr. Friendly would conspire with Lancelot to force a decision on them that is clearl y premature. When he leaves, Mrs. Lovebird calls Dr. Friendly and tells him that she i s furious with his breach of confidentiality and that he should stick to family practice, as he is not an oncology expert. Please respond to the following questions (approx. 500-700 wor

- 91. ds) using the template format provided for the assignment: Given Dr. Friendly’s longstanding relationship with the Lovebir ds, his insight into their processing and coping mechanisms, and the close family relatio nship he has witnessed between the Lovebirds and their son, did Dr. Friendly’s breach his professional 10/27/2016 Final Case Analysis: Confidentiality, Disclosure and Livid Love birds https://mycourses.excelsior.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-3200850-dt-co ntent-rid-31405097_1/courses/BHS.HSC312.Online.201610.201 612.s30047605/course%20wide… 3/3 responsibility to Mr. and Mrs. Lovebird by suggesting that Lanc elot discuss the Hospice option with the Lovebirds first? Use the following template for your assignment:

- 92. 1. Use Microsoft Word to create a document. 2. Copy/paste the title of the question. 3. Describe the most relevant ethical dilemma(s) presented (no more than two). 4. Briefly describe the primary issue or issues that are relevant i n the scenario with respect to the dilemma. 5. Identify the most relevant stakeholder(s) (no more than 3) an d briefly describe the situation from their perspective. 6. Analyze the dilemma, using scholarly discussion, from the pe rspective of the primary stakeholder (typically the patient). Include a discussion of at lea st two ethical theories or bioethics principles studied in the course that relate to the dil emma and issues you identified. Include any relevant legal concerns or requirements outlined in the readings. 7. Present your assessment, resolution or potential solutions for resolving the issue.

- 93. Remember that there are no right answers, per se, so reflective q uestions can be as appropriate as a firm conclusion. 8. Title page + APA formatted reference(s). A MEDICAL ETHICS ASSESSMENT OF THE CASE OF TERRI SCHIAVO TOM PRESTON University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA MICHAEL KELLY Swedish Medical Center and University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA The social, legal, and political discussion about the decision to stop feeding and hydration for Terri Schiavo lacked a medical ethics assessment. The authors used

- 94. the principles of medical indications, quality of life, patient preference, and contextual features as a guide to medical decision-making in this case. Their conclusions include the following: (a) the use of a feeding tube inserted directly in to the stomach constituted artificial treatment; (b) the treatment prolonged biological life but did not lead to a cure and did not restore health; (c) quality of life was absent for the patient, with no sensation and no motor or cognitive functioning; and (d) by preponderance of medical opinion, she would have chosen not to live in a persistent vegetative state. The authors find the withdrawal of treatment was permissible and correct. It was not a choice between living and dying, but a decision of when to allow dying consistent with the patient’s choice. The case of Terri Schiavo, vexing as it was, holds lessons for us all. The forceful public reactions to the medical and legal proceedings

- 95. leading to her demise showed a deep schism over the moral= religious issues inherent in how we die in the modern age of medi- cine. In our opinion, the political and legal wrangling detracted from the public understanding of the medical and bioethical issues involved in the case. Some might further argue that the case exposed a severe fault line in the bioethics approach to issues of this sort, or at least a limi- tation of the usefulness of bioethics. After all, the case never went under the scrutiny of a bioethics committee and there was no This article was written prior to release of the autopsy report on Terri Schiavo. Address correspondence to Tom Preston, 1128 22nd Ave. E., Seattle, WA 98112. E-mail: [email protected] 121 Death Studies, 30: 121–133, 2006 Copyright # Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

- 96. ISSN: 0748-1187 print/1091-7683 online DOI: 10.1080/07481180500455608 formal statement of medical ethics conveyed to the public in support of letting Terri die. The public media presentation of the case was in social, political, and legal terms, with sparse, if any, discussion of how bioethical principles might apply to the difficult issues involved. The absence of a classic medical ethics assessment was a lost opportunity to educate the public. In this article we apply the basic tenets of medical ethics to the medical decision-making process in the Schiavo case. Medical ethics, or bioethics, began as a means of giving physicians and other health care providers guidelines for handling ethical pro- blems that occur in the practice of medicine. It then developed as a method for dealing with new ethical issues, particularly those arising from procedures such as artificial kidney treatment (dialy-

- 97. sis), resuscitation, and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment ( Jonsen, Siegler, & Winslade, 1992). We use the technique of Jonsen, Siegler, and Winslade (2002), which focuses on four topics clinicians should take into account in assessing the ethical aspects of a medical decision: medical indications, patient preference, quality of life, and contextual features. Medical Indications Medical ethics begins by asking whether the proposed treatment or procedure is medically indicated—does it fulfill the goals of medicine? Using the principle of beneficence, we ask does this treatment maintain life, restore health, and prevent symptoms? Do the benefits outweigh the potential harm of the treatment? What were the medical ‘‘facts’’ of the Terri Schiavo case, and what can bioethics teach us about how to proceed when a next similar case occurs? Removing Terri Schiavo’s feeding tube was not a treatment per se, but rather the discontinuation of treatment with hydration and nutrition. Terri did not sense food in her mouth and did not have a swallowing reflex. Because she was unable

- 98. to swallow, she could not be fed through her mouth without a strong likelihood of choking to death, so the feeding tube was the only means of keeping her alive. The treatment under analysis is there- fore the continuation of fluids and nutrients through Terri’s feeding tube. The central question was whether continued treatment with the feeding tube was medically indicated. Was this treatment of 122 T. Preston and M. Kelly benefit to Terri, or was the treatment disproportionately burden- some and harmful to her? One of the goals of medicine is to maintain life or to prevent death. The goal, however, is not to prevent all death but to prevent untimely or inappropriate death. In this case, continued feeding certainly would have kept Terri alive, as it had done for 15 years.

- 99. Although in many cases the goal of maintaining life is pre- eminent, when the ethical issue is whether life should continue or be allowed to end, this goal is subsumed under other considerations. Whether death from stopping the treatment would have been considered timely or untimely depends on factors such as perceived patient preference, judgment of what would be best for her, and opinions about the quality of her life. Would continued treatment have relieved symptoms of pain and suffering? No. Terri had only involuntary reflexes, with no function above the brain stem. She had no cognitive function or awareness of her surroundings, and no physical or mental sensation of pain or suffering. Therefore treatment was not relieving suffering. Would continued treatment have restored health? Would it have cured the disease or improved functional status? Two neurol- ogists selected by Terri’s parents (who opposed ending treatment)

- 100. suggested that Terri’s smiles and movements represented cognition and sensation, whereas two neurologists selected by Terri’s husband and one selected independently by the court testified that Terri’s reflexes were involuntary and she was in a persistent veg- etative state from which she would never recover (see Cerminara’s introductory article for a detailed review of the related history). All five neurologists agreed that Terri had suffered enormous damage to her brain, such that most of her cerebral cortex, which controls conscious thought, was gone, replaced by spinal fluid. The biological probability for a cure of her condition was so minimal as to be effectively zero. In the second trial, the court heard conflicting evidence as to whether new therapy might succeed in restoring Terri’s brain func- tion and found no credible evidence that Terri would ever recover significant function. This finding was unanimously upheld on

- 101. appeal. Undeniably, the prognosis in this case was crucial to a sound ethical judgment, and any disagreement makes the decision difficult. We agree with the trial courts that claims of potential improvement with new therapies were without merit. The treatment Medical Ethics Assessment 123 offered no chance for restoring health. Because treatment was not relieving symptoms, and it held no reasonable chance for a cure or clinical improvement, there was no medical indication for contin- ued treatment with the feeding tube. Germane to the discussion is a related question: Was Terri Schiavo on life support, or was she merely being fed through a tube? Some argued that treatment with food and fluids should never be withdrawn from dying or permanently unconscious patients (e.g., Pope John Paul II, 2004). Feeding is natural, they said, and ‘‘merely being fed through a tube’’ is not life

- 102. support—it is different from stopping treatments such as artificial breathing with a mechanical ventilator. We all understand the emotion behind this argument when it is made to keep a loved one alive, but from a medical ethics perspective it is not correct. Medically, stopping feeding is no different from stopping a breathing machine that is keeping some- one alive. Air is also natural, and breathing is a natural function. Food and air are equally natural and essential to life. If a person is permanently unable to breathe, we can delay death with artificial breathing. If a person is permanently unable to swallow we can delay death by placing a feeding tube into the stomach and bypass- ing the need to swallow. It is as unnatural to pierce through the abdomen and place a tube into a patient’s stomach, and then pour food through the tube or pump it into the stomach with a machine, as it is to use a machine to blow air into a patient’s lungs. With artificial breathing,

- 103. the air at least goes in and out through the natural wind-pipe, while artificial feeding bypasses the natural process of swallowing food through the esophagus to the stomach. The mechanisms of arti- ficial feeding and breathing are different, but one is not more or less natural than the other. But, some argued, food and fluids are ordinary and natural and stopping them is ‘‘killing,’’ it is ‘‘starving’’ a person to death (e.g., Pope John Paul II, 2004). On the other hand, they said, it is allowable to disconnect a patient from a breathing machine because it is an extraordinary medical measure (see also, President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1983). But one is not extra- ordinary, whereas the other is ordinary. In its landmark report, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in 124 T. Preston and M. Kelly

- 104. Medicine concluded: ‘‘There is no basis for holding that whether a treatment is common or unusual, or whether it is simple or com- plex, is in itself significant to a moral analysis of whether a treatment is warranted or obligatory’’ (p. 87). Also, according to Florida stat- ute, a ‘‘Life-prolonging procedure means any medical procedure, treatment, or intervention, including artificially provided sustenance and hydration, which sustains, restores, or supplants a spontaneous vital function’’ (Health Care Advance Directives, Definitions, x765.101, 2004, emphasis added; see also xx765.301-309). This is consistent with medical understanding and the tenets of medical ethics. Terri Schiavo was on life-support because she could not survive without the fluid and nutrition treatment she was receiving. Nonmaleficence

- 105. Application of the principle of nonmaleficence (do no harm) leads us to ask, would continued feeding have been good treatment for Terri, or would it have harmed her? Would either maintaining or discontinuing the treatment cause harm out of proportion to benefit for her? Would removing Terri’s feeding tube be inhumane by causing ‘‘starvation’’ and pain? In comparison to withdrawing artificial breathing with a ventilator, stopping tube-feeding appears to be a long, drawn-out procedure during which the patient may suffer. But Terri had no sensation of thirst or hunger. She did not suffer when the feeding tube was withdrawn, and the absence of food and fluids did not cause suffering (Multi-Society Task Force on PVS, 1994). There is an important emotional difference between slow dying after withdrawal of food and water and the rapid death following disconnecting a patient from a respirator. One watches the patient dying slowly from absence of food and water and

- 106. might conclude, ‘‘They are starving her to death.’’ But families do not usually watch their loved one being disconnected from a breathing machine. If they did, they would say, ‘‘They are suffocating him to death.’’ Discomfort or pain is possible in the latter procedure only if the patient is not given sufficient sedative or pain medicine to obliterate symptoms. On the other hand, there is no discomfort associated with dehydration after withdrawal of a feeding tube in a patient with persistent vegetative state. Medical Ethics Assessment 125 Would continued treatment have harmed Terri? Unfortunately, many relatives or loved ones of patients on life-supporting therapy do not understand the consequences of continued treatment. Although Terri would not have perceived suffering had she remained alive, over the years or decades to come she inevitably would have acquired illnesses associated with aging and being

- 107. bed-ridden, which would have increased the psychological burden on her family. The larger question was whether Terri benefited or was harmed by dying. The answer to this rests in part on her quality of life if feeding had been continued. Certainty on this point is impossible and must take into account the complexity of the judg- ment of the value of living indefinitely in a persistent vegetative state. Whether Terri benefited or was harmed by dying also depends on determination of her personal preference, or her valuation of continued living in that condition. Autonomy, or Patient Preferences In our opinion, this is probably the most important ethical determi- nant of the case. There is little question that had Terri had an advance directive with a clear statement on whether she would want to continue living in a persistent vegetative state, the medical decision would have been according to her stated desire and there