First MI Last Name719.555.1212 H719.555.1313 CCitizenship US

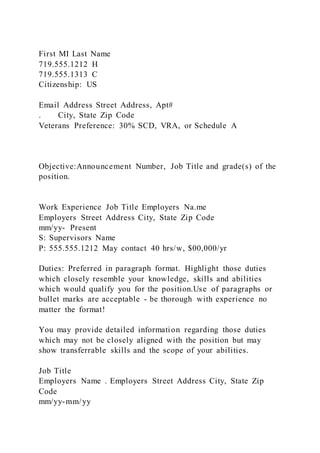

- 1. First MI Last Name 719.555.1212 H 719.555.1313 C Citizenship: US Email Address Street Address, Apt# . City, State Zip Code Veterans Preference: 30% SCD, VRA, or Schedule A Objective:Announcement Number, Job Title and grade(s) of the position. Work Experience Job Title Employers Na.me Employers Street Address City, State Zip Code mm/yy- Present S: Supervisors Name P: 555.555.1212 May contact 40 hrs/w, $00,000/yr Duties: Preferred in paragraph format. Highlight those duties which closely resemble your knowledge, skills and abilities which would qualify you for the position.Use of paragraphs or bullet marks are acceptable - be thorough with experience no matter the format! You may provide detailed information regarding those duties which may not be closely aligned with the position but may show transferrable skills and the scope of your abilities. Job Title Employers Name . Employers Street Address City, State Zip Code mm/yy-mm/yy

- 2. S: Supervisors Name P: 555.555.1212 May contact 40 hrs/w, $00,000/yr Duties: Preferred in paragraph format. Highlight those duties which closely resemble your knowledge, skills and abilities which would qualify yo1,1 for the position.Use of paragraphs or bullet marks are acceptable - be thorough with experience no matter the format! You may provide detailed information regarding those duties which may not be closely aligned with the position but may show transferrable skills and the scope of your abilities Job Title Employers Name Employers Street Address City, State Zip Code mm/yy- mm/yy S: Supervisors Name P: 555.555.1212 May 1=ontact 40 hrs/w, $00,000/yr Duties: Preferred in paragraph format. Highlight those duties which closely resemble your knowledge, skills and abilities which would qualify you for the position.Use of paragraphs or bullet marks are acceptable -be thorough with experience no matter · the format! You may provide detailed information regarding those duties which may not be closely aligned with the position but may show transferrable skills and the scope of your abilities. Job Title Employers Name Employers Street Address City, State Zip Code mm/yy- mm/yy S: Supervisors Name

- 3. P: 555.555.1212 May contact 40 hrs/w, $00,000/yr Duties: Preferred in paragraph format. Highlight those duties which closely resemble your knowledge, skills and abilities which would qualify you for the position; Use of paragraphs or bullet marks are acceptable - be thorough with experience no matter the format! · You may provide detailed information regarding those duties which may not be closely aligned with the position but may show transferrable skills and the scope of your abilities. Education mm/yy Master's of Arts in Organizational Management, GP A 3.85 Name of University City, State Zip Code mm/yy Bachelor's of Science in Human Resources Management, GPA 3.76 Name of University, City, State Zip Code mm/yy Diploma/GED Name of your High School/GED, City, State Zip Code Job Related Training mm/yy Basic Staffing and Placement, School Name mm/yy Workers Compensation, School Name mm/yy Processing Personnel Actions, School Name Honors, Awards mm/yy Veterans Preference Awards (Expeditionary Medals, Campaign Badge, Purple Heart) Other Information I certify that I can type 50+ words per minute and that the information within this resume is accurate. References: Include References on Resume or on a stand alone document

- 4. Relationship governance and learning in partnerships Marko Kohtamäki Department of Management, University of Vaasa, Vaasa, Finland Abstract Purpose – Relationship learning is a topic of considerable importance for industrial networks, yet a lack of empirical research on the impact of relationship governance structures on relationship learning remains. The purpose of this paper is to analyze the impact of relationship governance structures on learning in partnerships. Design/methodology/approach – This paper contributes to the closure of the research gap by examining sample data drawn from 42 interviews on the subject of 199 customer-supplier relationships within the Finnish metal and electronics industries. As a method, the paper applies cluster analysis and analysis of variance mean-comparison. Findings – The results of this paper show that balanced hybrid governance structures explain learning in partnerships, which suggests that certain combinations of relationship governance mechanisms (price, hierarchical, and social mechanism) produce the best learning outcomes in partnerships. Results suggest that managers should use hybrid relationship governance structures when governing their supplier partnerships. Research limitations/implications – The paper has some

- 5. limitations such as limited sample size, cross-sectional data, and difficulties due to measuring social phenomenon such as learning. Owing to the interview method being applied, research is bound to apply a sample data drawn from companies that operate in the west coast in Finland. These limitations need to be considered when applying the results. Practical implications – The results encourage managers to use different governance mechanisms simultaneously when managing their company’s supply chain partnerships. The result emphasizes the role of active relationship management. Originality/value – The paper is one of the first to empirically show that relationship learning is best facilitated by using various relationship governance mechanisms simultaneously. Trust needs to be complemented by hierarchical and possibly by price mechanism. Keywords Customer relations, Supplier relations, Learning, Partnership, Finland Paper type Research paper 1. Introduction The imperfect nature of industrial markets favors the use of more sophisticated mechanisms of relationship governance than mere competitive bidding to drive learning and innovation, within partnerships and business networks (Ahmadjian and Lincoln, 2001; Knight, 2002). Competitive bidding cannot foster learning, when supplier switching times are long. Thus, in partnerships,

- 6. competition or, in particular, competitive bidding is inefficient in terms of learning (Krause et al., 2000). Therefore, the interplay between price, hierarchical, and social governance mechanisms is particularly interesting in partnerships (Adler, 2001; Ghoshal and Moran, 1996). Following on Adler’s (2001) model, the present study proposes that relationship The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/0969-6474.htm This paper emerged from the research projects Dynamo and System. The financial support of the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation and the companies involved in this project is gratefully acknowledged. Relationship governance and learning 41 The Learning Organization Vol. 17 No. 1, 2010 pp. 41-57 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited 0969-6474 DOI 10.1108/09696471011008233

- 7. learning is best facilitated by the simultaneous use of different relationship governance mechanisms and that certain combinations of these mechanisms increase relationship learning more than others do. This research contributes to the current knowledge of partnerships by increasing understanding about the impact of relationship governance structures on learning in partnerships, which previous literature contends to be an important research gap (Nooteboom and Gilsing, 2004). Indeed, the research on relationship governance (Adler, 2001) has neglected the relationship learning view, while the scholars focusing on relationship learning have overlooked the governance viewpoint. This paper addresses the research gap by combining these literature streams into a coherent research model that explains how different combinations of relationship governance mechanisms (price, hierarchical, and social) have an impact on relationship learning. This study will also contribute by increasing our knowledge as to how supply chain partnerships should be governed in order to facilitate learning. While a vast amount of previous literature contends that learning requires trust (Dodgson, 1993; Rousseau et al., 1998), the present paper intends to study whether learning can be enhanced by combining trust (a social mechanism), relationship management (a

- 8. hierarchical mechanism), and competition between the suppliers (a price mechanism; Adler, 2001). 2. Relationship governance and learning Learning in partnerships This study approaches relationship learning by applying organizational learning theory (Fiol and Lyles, 1985). Since learning is context dependent (Holmqvist, 2003; Knight, 2002), it needs to be studied in both partnerships and networks. The argument is that the level of organizational integration, e.g. trust, between the organizational members affects learning and, thus, learning is different in teams than it is in inter-organizational networks or partnerships. Previous literature provides various definitions of relationship learning. The present study defines the relationship learning according to Selnes and Sallis (2003, p. 80) as: [. . .] a joint activity between a supplier and a customer in which the two parties share information, which is then jointly interpreted and integrated into a shared relationship-domain – specific memory [. . .] This definition of relationship learning underlines knowledge sharing, shared interpretation and the development of activities in a partnership alongside other definitions (Håkansson et al., 1999; Dyer and Hatch, 2004; Inkpen, 1996; Knight, 2002).

- 9. Relationship governance and learning Following the previous definitions of partnerships, the present study defines partnerships and networks as an intermediate form between markets and hierarchies (Thorelli, 1986; Ritter, 2007; Williamson, 1985). In other words, a vertical partnership is a customer-supplier relationship, which is long, integrated, and deeply rooted in the social relationships between the individuals that are active in the relationship (Macaulay, 1963; Sako, 1992; Ritter, 2007). Recent theory developments in the study of relationship governance argue that the most effective partnership governance structure is a hybrid, in which the customer employs several relationship governance mechanisms simultaneously to govern TLO 17,1 42 a single supply relationship (Figure 1; Adler, 2001; Heide, 1994; Ritter, 2007; Kohtamäki et al., 2006). The three relationship governance mechanisms that previous studies apply are termed price, hierarchical, and social mechanism (Adler, 2001; Powell, 1990; Bradach and Eccles, 1989; Hines, 1995; Heide, 1994). Previous empirical research has commonly operationalized

- 10. network governance in terms of sourcing policy, whether the customer applies single, dual, or multiple sourcing in their procurement policy (Dyer and Ouchi, 1993, pp. 55-8; Hines, 1995, 1996). This study adopts a more sophisticated approach and applies multiple indicators to define and measure each governance mechanism. In this study, relationship governance refers to a governance structure of a supplier relationship, which is constructed using a combination of price, hierarchical, and social mechanisms. The theory contends that a customer can steer the behavior of its suppliers by applying these mechanisms in different combinations (Adler, 2001). The following section describes the individual governance mechanisms in more detail, while the subsequent sections develop on their different combinations and their impact on relationship learning. Price as a mechanism of relationship governance refers to utilizing the competition between suppliers in the market to steer the relationship. Competition is known as an efficient mechanism, which is utilized not only in markets, but also in hierarchies and networks (Dyer and Hatch, 2004; Krause et al., 2000; Powell, 1990; Swedberg, 1994). However, when switching to an alternative partner becomes time-consuming and costly due to the unique resources and capabilities of the supplier, the market works

- 11. Figure 1. Effects of relationship governance structures on learning in partnerships Relational contracting Hybrid Low-trust hybridMarket Social Laissez-faire Coercive Supportive hierarchical R elationship learning HighLow L ow H ig h P ri ce

- 12. g ov er na nc e Hierarchical governance Note: Low social relationship governance in lower left triangles and high social relationship governance in upper right triangles Source: Adler (2001) Relationship governance and learning 43 imperfectly and other governance mechanisms are required to ensure learning and development in the relationship (Kohtamäki and Kautonen, 2008). Various scholars describe Toyota’s successful dual or multiple supplier policy within its supplier network, which utilizes competition without a constant need to change suppliers (Dyer and Hatch, 2004; Sako, 2004; Dyer and Nobeoka, 2000). Dual or multiple sourcing

- 13. enables a customer to use competition without sacrificing the long-term relationship, which facilitates development and learning in the relationship (Hines, 1995). Competition can prove a catalyst for developmental work, while the partners’ belief in the continuity of the relationship motivates the development. Gerlach (1992) defines the hierarchical governance mechanism as the “visible hand” of the manager in the organization. In this study, hierarchical governance refers to mechanisms such as the customer’s use of authority in the relationship and the hierarchical structures and processes that apply to the business relationship (Nishiguchi and Beaudet, 1998; Bensaou, 1999; Håkansson and Lind, 2004). Thus, when using hierarchical relationship governance, the customer steers, but also forces the development of the business relationship. Researchers have provided examples of customers’ use of authority and hierarchical structures. For example, Dyer and Hatch (2004) describe three methods, which Toyota applies to support supplier development: supplier association, consulting groups, and learning teams. This means that Toyota facilitates supplier learning with conferences and smaller learning forums, e.g. learning teams, but also provides a consulting service to its suppliers (Sako, 2004; Dyer and Nobeoka, 2000). These results suggest that Toyota does not only try to develop trusting relationships with its suppliers, but seeks to actively facilitate learning in its

- 14. partnerships and supplier network. Our study follows the view by analyzing the role of hierarchical relationship governance in partnership learning. A whole stream of literature has examined trust and social governance in business relationships (Adler, 2001; Granovetter, 1985; Ouchi, 1980). In this context, social governance refers to trust (Zaheer et al., 1998), open interaction and a feeling of shared destiny (Adler, 2001; Ghoshal and Moran, 1996). A number of studies emphasize the significance of these phenomena for learning in relationships (Håkansson et al., 1999; Selnes and Sallis, 2003). However, as learning needs to be focused in order to create value for a particular business relationship, trust alone is an inadequate governance mechanism and needs to be supported by other mechanisms (Adler, 2001; Kohtamäki and Kautonen, 2008). The role of relationship governance structures on learning Based on Adler’s (2001) model, the present study suggests that learning in relationships is best facilitated by a combination of price, hierarchy, and the social relationship governance mechanisms, rather than a sole reliance on any one of these single mechanisms. In the following discussion of the impact of different combinations of governance mechanisms on relationship learning, the degree of each governance mechanism in a particular governance structure is simply regarded as being either high or low. Figure 1 displays eight different combinations of

- 15. the three governance mechanisms, that is, eight alternative relationship governance structures. This study proposes that they have a varying impact on learning in business relationships. Since, the conceptual evidence in previous literature is not clear enough to warrant a formal hypothesis, the following discussion declines to construct formal hypotheses but TLO 17,1 44 instead presents preliminary conceptual evidence as a basis for the subsequent exploratory empirical analysis. Figure 1 suggests that governance structures are constructed on the basis of price, hierarchical, and social mechanisms. Thus, the present study suggests there are basically four different combinations of relationship governance mechanisms, as in the remainder of the eight clusters the customer either applies a single mechanism (price, hierarchical, or social) or does not apply any of them (a laissez- faire approach). The four clusters, in which a customer uses two or three different mechanisms simultaneously, are here termed relational governance, supportive hierarchical governance, low-trust hybrid governance, and hybrid governance.

- 16. By relational governance, the model refers to a combination of price and social mechanism (Macaulay, 1963). Theory suggests that just as competitive bidding may force the supplier to develop the customer relationship (Krause et al., 2000); trust could increase its partners’ willingness to share knowledge within it (Håkansson et al., 1999). On the other hand, unreasonable use of competitive bidding could lead to a decrease in a supplier’s commitment to the relationship, and thus unwillingness to invest in relationship development. The findings of the previous studies recommend dual or multiple supplier policies, which are able to simultaneously produce competition, stability, and trust in the relationship (Dyer and Hatch, 2004; Hines, 1995; Dyer and Ouchi, 1993). Previous studies also suggest that the combination of hierarchical and social mechanisms can be effective in terms of relationship learning (Adler, 2001; Kohtamäki et al., 2006). Relationship learning may require an open and trusting atmosphere, but also a little pressure created by the customer. While previous scholars show that mutual learning requires trust between the partners (Takeuchi and Nonaka, 1995; Selnes and Sallis, 2003), Adler’s (2001) model argues that partnerships should be managed and facilitated (Möller et al., 2005). This suggests that hierarchical governance is fundamental in partnerships (van der Meer-

- 17. Kooistra and Vosselman, 2000), but its use should be delicate, so that it will not cause distrust (Ghoshal and Moran, 1996). Hence, a customer should have sufficient competence to apply hierarchical steering without causing distrust. The paper defines the third combination of governance mechanisms as a low-trust hybrid (Adler, 2001). In this alternative, the combination of price and hierarchical mechanism affects learning in partnerships. When talking of this low-trust hybrid relationship governance structure, the researcher is referring to a business relationship, which is governed by hierarchical structures and some competition, but not by trust, perhaps due to the loosely coupled organization of the relationship. This particular relationship governance structure might not be efficient in terms of new knowledge creation, because learning requires trust, but could well be efficient in terms of keeping the overall costs of the relationship down. The fourth alternative relationship governance structure is here termed a hybrid (Heide, 1994; Hines, 1995; Håkansson and Lind, 2004; Sako, 2004). In a hybrid governance structure, the customer applies all three governance mechanisms simultaneously. The present study suspects that the hybrid governance structure facilitates relationship learning and relationship performance, by providing a moderate level of competition and hierarchical direction, as well as an

- 18. open atmosphere in which to share and develop knowledge and learning within the partnership. Relationship governance and learning 45 In summary, the present study focuses on the impact of relationship governance structures on relationship learning by applying Adler’s (2001) model of relationship governance. The study explores which kinds of relationship governance structures can be discerned within 199 business relationships in order to see how various combinations of governance mechanisms affect relationship learning. 3. Research methodology and data Data collection The study uses cluster analysis to analyze sample data from 199 customer-supplier relationships. The data were collected from 26 (45 percent medium-sized/55 percent large) business units in the metal and electronics industries in Finland. Data were collected in interviews of 42 supply directors (three respondents), supply managers (26 respondents), or strategic buyers (13 respondents). Most of the respondents (39 of

- 19. 42), analyzed five relationships each, while the rest (three respondents) analyzed a few individual relationships by using a web-based questionnaire. The researcher controlled for the potential effect of the respondent’s role within the organization (director, supply manager, and strategic buyer) on their responses, by comparing the responses of directors, managers, and buyers on the key study variables by using t-test. However, the test yielded no statistically significant differences between the respondents in different roles. The companies were chosen from western Finland for research economic reasons, as the data was collected in personal interviews and the researcher had to travel to all the respondent companies. Measures Previous studies (Selnes and Sallis, 2003; Kohtamäki and Kautonen, 2008; Krause et al., 2000) contributed to the development of the items in the questionnaire, which uses Likert-scale measures (1, fully disagree; 5, fully agree; Appendix 1). The researcher transferred items into four different composite variables (price, hierarchical, social governance mechanisms, and relationship learning) for the cluster analysis and mean comparisons. The study tested the items by using partial least squares approach. Researcher tests the constructs by using Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability and average variance extracted (AVE). The researcher also tests both item and construct discriminant validity, inspect skewness, and kurtosis values of

- 20. all constructs as well as checks the data for possible common method bias and multicollinearity. The main determinants of the price mechanism are internal competition within the network, potential suppliers in the market and the development of a competitive atmosphere among the suppliers (Hines, 1996). The four variables measuring the price mechanism were developed on the basis of Kohtamäki et al. (2008) (Krause et al., 2000). Items measuring price were: frequency of bidding; number of potential suppliers in the market; number of suppliers for a given component; and development of a competitive atmosphere in the relationship. Previous studies define hierarchical governance as consisting of several different variables, which measure both the customer’s use of authority and hierarchical structures in the relationship (Hines, 1996; Ellram, 2002). Measures of this dimension were modified on the basis of Kohtamäki et al. (2008) (Krause et al., 2000). This study measures hierarchical governance by using five variables: level of quality and management system requirements; urge to affect supplier’s procedures; supplier’s TLO 17,1 46

- 21. involvement in customer’s production and quality meetings; use of supplier auditing; and exactness of instructions given to supplier. Previous empirical research has studied social governance extensively and scholars have used various scales to report their findings. This research applies the scale used by Selnes and Sallis (2003) (Kohtamäki et al., 2008), which reflects the two dimensions of social governance defined as having a shared purpose and trust. Four variables measure social governance: development of shared understanding; level of strategic discussions with the supplier; customer’s willingness to develop trust in the relationship; and willingness to seek a common understanding. The present study measures learning with four items based on the conceptualizations of Selnes and Sallis (2003). The variables are: development of new ideas in the relationship; economic value of new ideas in the relationship; shared problem solving and knowledge sharing; and explication of the most conflicting problems. The reliability of the constructs was measured by deriving values for Cronbach’s alpha (threshold value 0.6), composite reliability (0.7), and AVE (0.5). Almost all the constructs show fairly satisfactory Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability and AVE

- 22. values (Chin, 1998; Cool et al., 1989), although AVE value for price governance were a little low and below the threshold (0.5). As all the items, except one measuring price, exceed the typical threshold value set for the item loading (0.6) and the loading of each item with their respective construct is statistically significant, researcher can safely conclude satisfactory item discriminant validity. As the price mechanism achieved fairly satisfactory Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values, researcher decided to keep all the items in order to maintain the construct’s theoretical consistency. All constructs showed satisfactory discriminant validity as AVE values exceeded the squared latent variable correlations (Cool et al., 1989) even if the low AVE value of price governance suggest that those measures need development in future studies (Chin, 1998). The researcher also decided to test the skewness and kurtosis of each construct and found every construct exceeding the typical threshold. The data were also tested for common method bias using Harman’s (1976) one factor test, which the researcher conducted by using principal axis factoring and interpreting the unrotated factor solution (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). The test showed that common method variance was not present in the data as the items loaded on four factors, which accounted for 61 percent of the total variance of which the first factor accounted for only 33 percent.

- 23. Finally, researcher analyzed the data due to possible multicollinearity of the constructs, but the correlation matrix (Appendix 2) and vif-value shows that in this dataset multicollinearity does not create a problem. Vif-value for all the constructs remained well below 2, while the typical threshold is 10 (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). In summary, based on the statistical tests reported above, the items and constructs appear suitable for further analysis (Table I). Methods and data analysis The present study analyzes the data in two phases. The first phase of the analysis applies cluster analysis in order to find the clusters consisting of business relationships governed by similar relationship governance structures and, thus, differing from other clusters. In the second phase, these clusters of business relationships are mean Relationship governance and learning 47 compared in terms of learning in order to discover which kinds of governance structures increase learning in business relationships. This study applies non-hierarchical cluster analysis and the k-

- 24. means method. In the k-means method the cases are grouped into homogenous groups (Ketchen and Shook, 1996), while the number of clusters is given by the researcher. In this study, cases are clustered by using the composite variables of the three governance mechanisms (price, hierarchy, and social). During the analysis, various cluster solutions were tested, but the researchers decided to apply a four-cluster solution, as it was the most informative and clear from the point of view of results. As the cluster analysis recognizes some groups and ignores some potential ones, it means that the ones being found are interpreted as viable. According to the configurational contingency approach, only those forms which are viable can be identified in the empirical world (Gerdin and Greve, 2004). Thus, if some combination of governance structure is not found in the empirical world, the approach would suggest that such a combination is not viable. After the cluster analysis, the study compares the resulting groups by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) mean-comparison. Resulting groups are mean-compared in terms of learning by using both the four individual learning items and the respective composite variable, to study whether relationship learning varies statistically significantly between different clusters. The study uses also post hoc analysis (Scheffe’s test) to test how learning varies between

- 25. each recognized cluster (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). This analysis shows which clusters differ from each other in terms of relationship learning. During the analysis, the study applies SPSS (version 15) to conduct the cluster analysis and mean comparisons. 4. Results Table II shows the results of the cluster analysis. In the analysis, researchers found four clusters, which clearly varied in terms of the relationship governance structures used in the cases. These clusters, which consist of relationships that are governed by Relationship governance structure (clusters) Governance mechanisms Social Market Supportive hierarchical Hybrid Price governance 2.17 3.68 2.43 3.74 Hierarchical governance 2.40 2.67 3.89 3.79 Social governance 2.94 2.57 4.15 4.09 Number of cases in a given cluster 31 30 81 54 Note: Figures are average scores of respondents’ responses on a Likert scale of 1-5 Table II. Average scores of relationship governance mechanisms of different clusters Skewness Kurtosis Cronbach’s alpha Composite reliability AVE

- 26. Price governance 0.12 0.26 0.67 0.71 0.41 Hierarchical governance 20.34 20.30 0.75 0.82 0.50 Social governance 20.64 0.11 0.77 0.86 0.60 Relationship learning 20.42 0.17 0.80 0.87 0.62 Table I. Skewness, kurtosis, Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values of all the constructs TLO 17,1 48 various relationship governance structures, are here termed: social, market, supportive hierarchical, and hybrid. While clusters are reported in columns, rows present the three governance mechanisms, which were used as criteria when clustering the cases. In the cluster of deep-rooted social governance, the relationships are governed only by using an intermediate social mechanism. The results show that in this cluster where the values of all the governance mechanisms stay below three, the value of the social mechanism is only very slightly below. It seems that in these relationships, the customer is either incapable or unwilling to use either price or hierarchical mechanisms

- 27. to govern the supplier relationship. The second cluster includes market-governed supplier relationships. Customers govern these relationships by using a strong price mechanism, but the use of social and hierarchical relationship governance is at a low level. It seems that in these partnerships, the customer intends to use the threat of competition to force the supplier to develop the customer relationship. The third cluster consists of supplier relationships governed by using supportive hierarchical governance. By supportive hierarchical governance, the researcher means that the supplier relationships are governed by using strong hierarchical and social governance mechanisms. In these partnerships, customers seem to be able to use both structures and requirements simultaneously without causing distrust. Governance is two-dimensional, showing that companies use various mechanisms simultaneously. Finally, the fourth cluster consists of hybrid governed supplier relationships. In these relationships, customers are willing and able to apply all three mechanisms simultaneously in a balanced manner. After the cluster analysis, the researcher mean-compared the four groups in terms of learning. In Table III, the last column on the right describes the value of the composite variable of learning formed from the four individual items. This study applies the ANOVA post hoc test (Scheffe) to analyze the differences between clusters. Scheffe’s

- 28. test enables researchers to compare learning between each cluster in order to interpret Learning cluster Development of new ideas Economic value of new ideas Shared problem solving and knowledge sharing Explication of the most conflicting problems Learning 1. Social 2.23 2.13 2.42 3.06 2.46 2. Hybrid 3.26 2.70 3.54 4.35 3.46 3. Market 2.03 1.93 2.27 3.20 2.36 4. Supportive hierarchical 2.92 2.77 3.71 4.17 3.39 Average 2.77 2.53 3.25 3.90 3.11 Scheffe’s test (a) (b) (a) (a) (a) Notes: Scores are averages of the respondents’ responses measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 5; (a) all the differences between relationships governed by social,

- 29. market, hybrid, and supportive hierarchical relationship governance structures are statistically significant at a significance level of ,0.05, except the difference between social and market-governed relationships and hybrid and supportive hierarchically governed relationships; (b) the difference between relationships governed by social and supportive hierarchical governance structures and between hybrid and market-type relationship governance structures are statistically significant at a significance level of ,0.05, but the difference between social and market-governed, social and hybrid-governed, market and supportive hierarchically governed relationships is not Table III. Average scores of different groups in terms of learning Relationship governance and learning 49 how learning differs between all the different clusters (i.e. between social and market, or hybrid and supportive hierarchical). Analysis based on the composite variable shows that learning does not vary statistically significantly between supportive hierarchical

- 30. and hybrid governed clusters and between social and market governed clusters. However, learning does vary statistically significantly in all the other combinations, such as hybrid and social, hybrid and market, supportive hierarchical and social, and supportive hierarchical and market. These results support the interpretation that learning is highest in hybrid and supportive hierarchically governed clusters of relationships and lowest, in social and market-governed clusters of relationships. Interestingly, learning is actually higher in social than in market-governed relationships. However, this difference is not statistically significant. Observations are by far similar, whether one looks at results of the composite variable or three of the four single items (development of new ideas, shared problem solving and knowledge sharing and explication of the most conflicting problems). However, results slightly differ when looking at one of the learning items (economic value of new ideas). With this particular item, the results differ slightly from the other items, as the differences between social and hybrid and market and supportive hierarchically governed relationships are not statistically significant, while they are with the rest of the items. However, also with this item the differences between social and supportive hierarchically governed relationships and between hybrid and market-governed relationships are statistically significant, which supports researcher’s interpretation of

- 31. the results. Table III shows all the results of the mean- comparisons. Finally, the analysis shows that in partnerships, companies often use various relationship governance structures to govern a partnership. The results provide evidence that supportive hierarchical and hybrid forms of governance are more effective in terms of learning than social or market governance. The results suggest that in order to support learning in the partnership, customers need to develop hierarchical structures, require developmental efforts from the suppliers and to maintain strong social relationships. In summary, Figure 2 shows the empirically found clusters (in italic) with the average scores of relationship learning. 5. Conclusions and discussion The effect of governance structures on learning in partnerships The present study stresses the impact of relationship governance on learning in partnerships. As, according to prior studies, learning is important for business performance, and as industrial networks cannot often be governed only by using competitive bidding due to long partner switching times, learning needs to be facilitated by using other forms of relationship governance, such as social and hierarchical governance (Adler, 2001). As some of the prior studies have emphasized the role of trust on learning (Håkansson et al., 1999), the present study argues that trust

- 32. needs to be complemented by the use of at least a hierarchical mechanism. The results emphasize the role of both relationship management and trust. The empirical analysis shows that relationship governance structures have an impact on learning in the partnership. Learning is highest in partnerships governed by supportive hierarchical or hybrid governance structures in comparison to market and socially governed ones. Again, supportive hierarchical governance refers to supply relationships, in which the customer applies both hierarchical and social governance TLO 17,1 50 mechanisms, while hybrid governance structures signify a relationship utilizing the three mechanisms (namely price, hierarchical, and social). In contrast, in market-governed relationships, the customer only uses the price mechanism, while in the socially governed relationships, the customer applies only a social mechanism at an intermediate level. This result parallels those of previous empirical studies. First, the result supports Adler’s (2001) model of organizati on of an economic system indicating that parties often apply the various mechanisms simultaneously and, thus,

- 33. gain learning in their supply partnerships. This particularly contributive empirical result suggests that customers need competencies to apply various mechanisms simultaneously. Customers need to be able to balance different mechanisms in order to utilize them simultaneously (Gustafsson, 2002; Kohtamäki et al., 2006); according to Barringer and Harrison (2000), managing partnerships is like “walking a tightrope.” The results seem to suggest placing emphasis on hierarchical and social governance. However, the results do not preclude the advantages of the market mechanism, when it is used in a balanced way, as in hybrid- governed relationships, which were found to be the most efficient in terms of learning. However, these results do question the efficacy of an extreme market mechanism in partnerships (Krause et al., 2000). In partnerships, the threat of competition on its own is apparently not sufficiently credible to increase development effort, but an unfair, unsystematic, and Figure 2. Effects of relationship governance structures on learning in partnerships Relational contracting Hybrid

- 35. ov er na nc e Hierarchical governance Notes: Empirically found clusters in italic, with the average scores of learning; low social relationship governance in lower left triangles and high social relationship governance in upper right triangles Relationship governance and learning 51 implicit use of competitive bidding can cause distrust, which, in turn, can discourage information sharing and even prohibit learning. These results seem to highlight the significance of social governance. Owing to the high instance of social governance in all the groups of high partnership learning, trust and the feeling of shared purpose seem to play a significant role in supporting learning. According to the results, an increase in the level of social

- 36. governance leads to an increase in partnership learning. These results demonstrate support for the previous research results of, for example, Zaheer et al. (1998) (Håkansson et al., 1999) who emphasized the significance of trust in business relationships. The results place emphasis on network management by suggesting that social mechanisms should be complemented by the use of hierarchical mechanisms in order to gain learning. These results provide support for some prior studies (Krause et al., 2000; Liker and Choi, 2004; Sako, 2004) that have also suggested a few practical tools to assist suppliers in their development (Dyer and Hatch, 2004; Sako, 2004). According to those studies, various methods, such as supplier associations, consulting groups, and learning teams can help to realize the development potential of suppliers. The result of this study is particularly contributive to management and organizational learning theory, as it suggests that in the unique context of partnership, ability to manage relationship by applying various mechanisms simultaneously results in increased learning. Thus, learning should be facilitated by using various governance mechanisms simultaneously. This is one of the first studies that demonstrate this result by using empirical data in the context of partnership. How to govern partnerships?

- 37. The present study suggests that the partnership governance structure should be balanced – utilizing at least the hierarchical and social governance mechanisms. The customer should be able to put pressure upon the supplier to develop relationship processes, without the suppliers feeling that the customer is only doing it for opportunistic reasons, in other words, a win-win outcome is available to both the customer and supplier. These results mean that industrial customers need a management system which defines the goals, implementation, and follow-up processes of relationship development. This system needs to be built up together with the supplier. This shared planning and implementation of relationship management systems will support the development of trust and a feeling of shared purpose. These ideas seem to integrate the relationship governance approach that has been applied in this study and the ideas of the IMP group (Ford and Håkansson, 2006), which suggest that reciprocal interaction is the key to learning and development in a business relationship. Since this study suggests that a customer should be able to simulta neously manage the relationship and develop trust, and as the study suggests that this could be done by engaging the suppliers in a shared planning and development process, it seems that there is a call for theory that emphasizes shared relationship management and joint

- 38. value co-creation. Limitations and research implications Although the results of this study are important, this research does have some limitations. First, the dataset is a sample from Finnish companies from the metal and TLO 17,1 52 electronic industries that operate in the west coast in Finland. Larger and perhaps comparative international research data is needed to test the research model and the generalizability of these results. Second, the data is cross - sectional, which suggests that the results of this study should be tested with longitudinal data in order to capture the development of the relationships over time – and, indeed, the actual learning process. Third, as the measurement of these phenomena is difficult, qualitative research is needed to verify the findings, but also to create knowledge concerning the mechanisms of learning in partnerships. However, despite the limitations, the present study gives an interesting and theoretically contributive viewpoint and provides a basis for future studies of the relationship between partnership governance structures and learning.

- 39. References Adler, P.S. (2001), “Market, hierarchy, and trust: the knowledge economy and the future of capitalism”, Organization Science, Vol. 1 No. 2, pp. 215-34. Ahmadjian, C.L. and Lincoln, J.R. (2001), “Keiretsu, governance, and learning: case studies in change from the Japanese automotive industry”, Organization Science, Vol. 12 No. 6, pp. 683-701. Barringer, B.R. and Harrison, J.S. (2000), “Walking a tightrope: creating value through interorganizational relationship”, Journal of Management, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 367-403. Bensaou, M. (1999), “Portfolios of buyer-supplier relationships”, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 40 No. 4, pp. 35-44. Bradach, J.L. and Eccles, R.G. (1989), “Markets versus hierarchies: from ideal types to plural forms”, Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 97- 118. Chin, W.W. (1998), “The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling”, in Marcoulides, G.A. (Ed.), Modern Methods in Business Research, Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 295-336. Cool, K., Dierickx, I. and Jemison, D. (1989), “Business strategy, market structure and risk-return relationships: a structural approach”, Strategic Management

- 40. Journal, Vol. 10 No. 6, pp. 507-22. Dodgson, M. (1993), “Organizational learning: a review of some literatures”, Organisation Studies, Vol. 14 No. 3, pp. 375-94. Dyer, J.F. and Nobeoka, K. (2000), “Creating and managing a high-performance knowledge-sharing network: the Toyota case”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 21 No. 3, pp. 345-67. Dyer, J.F. and Ouchi, W.G. (1993), “Japanese-style partnerships: giving companies a competitive edge”, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 35 No. 1, pp. 51-63. Dyer, J.H. and Hatch, N.W. (2004), “Using supplier networks to learn faster”, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 45 No. 3, pp. 57-63. Ellram, L.M. (2002), “Supply management’s involvement in the target costing process”, European Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 235-44. Fiol, C.M. and Lyles, M.A. (1985), “Organizational learning”, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 10 No. 4, pp. 803-4. Ford, D. and Håkansson, H. (2006), “The idea of business interaction”, The IMP Journal, Vol. 1 No. 1, pp. 4-27. Relationship governance and

- 41. learning 53 Gerdin, J. and Greve, J. (2004), “Forms of contingency fit in management accounting research – a critical review”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 29 Nos 3-4, pp. 303-26. Gerlach, M.L. (1992), Alliance Capitalism: The Social Organization of Japanese Business, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. Ghoshal, S. and Moran, P. (1996), “Bad for practice: a critique of the transaction cost theory”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 13-47. Granovetter, M. (1985), “Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness”, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 91, pp. 481-510. Gustafsson, M. (2002), Att leverera ett kraftwerk: Förtroende, kontrakt och engagemang i internationellprojektindustri, Åbo Akademis Förlag, Åbo. Håkansson, H. and Lind, J. (2004), “Accounting and network coordination”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 29, pp. 51-72. Håkansson, H., Havila, V. and Pedersen, A.-C. (1999), “Learning in networks”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 28 No. 5, pp. 443-52.

- 42. Harman, H.H. (1967), Modern Factor Analysis, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. Heide, J.B. (1994), “Interorganizational governance in marketing channels”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 58 No. 1, pp. 71-85. Hines, P. (1995), “Network sourcing: a hybrid approach”, International Journal of Purchasing & Materials Management, Vol. 24 No. 5, pp. 18-24. Hines, P. (1996), “Purchasing for lean production: the new strategic agenda”, International Journal of Purchasing & Materials Management, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 2-10. Holmqvist, M. (2003), “A dynamic model of intra- and interorganizational learning”, Organization Studies, Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 95-123. Inkpen, A.C. (1996), “Creating knowledge through collaboration”, California Management Review, Vol. 39 No. 1, pp. 123-40. Ketchen, D.J. and Shook, C.L. (1996), “The application of cluster analysis in strategic management research: an analysis and critique”, Strategic Management Journal., Vol. 17 No. 6, pp. 441-58. Knight, L. (2002), “Network learning: exploring learning by interorganizational networks”, Human Relations, Vol. 55 No. 4, pp. 427-54. Kohtamäki, M. and Kautonen, T. (2008), “Conceptualising the dimensions of sourcing strategy:

- 43. a governance-based approach”, International Journal of Value Chain Management, Vol. 2 No. 2, pp. 206-28. Kohtamäki, M., Vesalainen, J., Varamäki, E. and Vuorinen, T. (2006), “The governance of a strategic network: supplier actors’ experiences in the governance by the customer”, Management Decision, Vol. 44 No. 8, pp. 1031-51. Krause, D.R., Scannell, T.V. and Calantone, R.J. (2000), “A structural analysis of the effectiveness of buying firms’ strategies to improve supplier performance”, Decision Sciences, Vol. 31 No. 1, pp. 33-55. Liker, J.K. and Choi, T.Y. (2004), “Building deep supplier relationships”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 82 No. 12, pp. 104-13. Macaulay, S. (1963), “Non-contractual relations in business: a preliminary study”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 28 No. 1, pp. 55-67. Möller, K., Rajala, A. and Svahn, S. (2005), “Strategic business nets-their type and management”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 58 No. 9, pp. 1274-84. TLO 17,1 54 Nishiguchi, T. and Beaudet, A. (1998), “Case study: the Toyota

- 44. Group and the Aisin Fire”, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 40 No. 1, pp. 49-59. Nooteboom, B. and Gilsing, V.A. (2004), Density and Strength of Ties in Innovation Networks: A Competence and Governance View, Eindhoven Centre for Innovation Studies, Eindhoven. Ouchi, W.G. (1980), “Markets, bureaucracies and clans”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 25, pp. 129-41. Podsakoff, P.M. and Organ, D.W. (1986), “Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects”, Journal of Management, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 531-44. Powell, W.W. (1990), “Neither market nor hierarchy: network forms of organization”, Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol. 12, pp. 295-336. Ritter, T. (2007), “A framework for analyzing relationship governance”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 22 No. 3, pp. 196-201. Rousseau, D.M., Sitkin, S.B., Burt, R.S. and Camerer, C. (1998), “Not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 23, pp. 393-404. Sako, M. (Ed.) (1992), Prices, Quality and Trust, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Sako, M. (2004), “Supplier development at Honda, Nissan and Toyota: comparative case studies of organizational capability enhancement”, Industrial and

- 45. Corporate Change, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 281-308. Selnes, F. and Sallis, J. (2003), “Promoting relationship learning”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 67 No. 3, pp. 80-95. Swedberg, R. (1994), “Markets as social structures”, in Smelser, N.J. and Swedberg, R. (Eds), Handbook of Economic Sociology, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, pp. 255-84. Tabachnick, B.G. and Fidell, L.S. (Eds) (2007), Using Multivariate Statistics, Pearson, Boston, MA. Takeuchi, H. and Nonaka, I. (1995), The Knowledge-Creating Company, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Thorelli, H.B. (1986), “Networks between markets and hierarchies”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 37-51. van der Meer-Kooistra, J. and Vosselman, G.J. (2000), “Management control of interfirm transactional relationships: the case of industrial renovation and maintenance”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 25, pp. 51-77. Williamson, O.E. (Ed.) (1985), The Economic Institutions of Capitalism, The Free Press, New York, NY. Zaheer, A., McEvily, B. and Perrone, V. (1998), “Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance”,

- 46. Organization Science, Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 141-59. Further reading Kautonen, T. and Kohtamäki, M. (2006), “Endogenous and exogenous determinants of trust in inter-firm relations: a conceptual analysis based on institutional economics”, Liiketaloustieteellinen Aikakauskirja, Vol. 3, pp. 277-95. Kohtamäki, M., Vuorinen, T., Varamäki, E. and Vesalainen, J. (2008), “Analyzing partnerships and strategic network governance”, International Journal of Networking and Virtual Organizations, Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 135-54. Relationship governance and learning 55 Appendix 1 Items and variables Mean SD Loading Price mechanism Bids from competitors of this supplier are frequently requested 2.58 0.98 0.67 There are numerous potentially substitutive

- 47. suppliers 3.21 1.19 0.81 Similar or closely comparable components have several suppliers for us (multiple source) 2.78 1.37 0.33 Supplier is reminded of the highly competitive situation constantly, which is done in order to have a highly competitive atmosphere 3.16 1.16 0.72 Hierarchical mechanism We present very specific requirements for the supplier’s quality and management systems 3.92 1.15 0.64 We intend to influence the supplier in a very active manner 3.88 0.99 0.64 Supplier’s representatives actively participate in production or development meetings 3.20 1.26 0.79 We audit supplier’s processes using a specific method 2.80 1.50 0.71 Supplier has been given very specific written instructions on how to react to delivery problems 3.43 1.22 0.68 Social mechanism Customer tries to develop trust and a feeling of community by systematically organizing different shared meetings and training in which the participants are urged to develop a shared understanding 3.12 1.19 0.77 Customer discusses all the relevant issues related to supplier’s operations and strategies with the supplier 3.52 1.27 0.86 Customer attempts to develop trust by acting in a trustworthy manner themselves 4.18 0.86 0.69

- 48. Problems in the relationship are dealt with constructively, because the customer wants to seek a shared understanding 4.02 1.07 0.77 Learning In this relationship new ideas for development are often born 2.77 1.03 0.85 Some of these ideas have major economic significance for the customer’s and/or supplier’s business 2.53 1.06 0.78 In this relationship, we solve problems together and share knowledge actively 3.25 1.10 0.85 In this relationship we dare to discuss even the most contentious problems so that they can be solved 3.90 1.06 0.78 Note: All the variables were measure on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1, fully disagree; 5, fully agree) Table AI. List of variables used in the study TLO 17,1 56 Appendix 2 About the author

- 49. Marko Kohtamäki works as a Research Director in Research Group of “Strategy, Networks and Enterprise” at the University of Vaasa, Finland. He takes special interest in business networks and strategic management. Marko Kohtamäki can be contacted at: [email protected] Price governance Hierarchical governance Social governance Relationship learning Price governance 1 Hierarchical governance 0.02 1 Social governance 20.10 0.67 * 1 Relationship learning 0.06 0.54 * 0.64 * 1 Note: *Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed) Table AII. Correlations between average variables (off-diagonal elements) Relationship governance and learning

- 50. 57 To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: [email protected] Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Outsourced marketing: it’s the communication that matters Matthew Walker University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA, and Melanie Sartore and Robin Taylor East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA Abstract Purpose – Outsourcing has been promoted as one of the most powerful trends in the modernization of marketing operations. The rationale for such an undertaking includes a variety of factors but is generally predicated on fiduciary considerations. The purpose of this article is to examine the issues with, and the empirical consequences of, outsourcing within the intercollegiate marketing context. Design/methodology/approach – This is an exploratory mixed-

- 51. methods study incorporating qualitative and quantitative data to investigate outsourcing specifically related to the communication-employee commitment relationship. Findings – Results from study 1 reveal that marketing directors perceive outsourcing as critical but also experience dissatisfaction with the level, frequency, and direction of communication. Results from study 2 indicate that an explicit and positive relationship exists between employee satisfaction with communication and their resultant commitment to the organization. Research limitations/implications – Owing to the exploratory nature of the study and a relatively small sample, the conclusions are tempered until subsequent studies have been performed. As well, specific moderating variables (e.g. size, culture, budget) were not included in this initial inquiry and as such may add considerable variance explained to the proposed relationship. Practical implications – First, the authors suggest that managing the “right commitment” is essential for marketing departments when working with an outsourcing agency. Second, the authors call attention to the importance of certain contextual factors (e.g. shared knowledge, mutual dependency, and organizational linkage) that may serve to improve the outsourcing partnership. Originality/value – Few papers have explored the communication-commitment relationship, particularly with regards to outsourcing. Consequently, this study adds to the research by examining

- 52. how intercollegiate marketing employees perceive and react to an outsourcing partnership. Building on additional work in this area, the research focuses on several aspects of the communication-commitment framework not previously examined. Keywords Marketing, Outsourcing, Partnership, Universities Paper type Research paper Introduction The idea of marketing a product or service to the public is a function so central to a business that it requires careful nurturing and a considerable amount of personal attention. Accordingly, businesses who wish to convey the salient aspects of their product or service offerings may do so in a creative but sometimes costly manner. As a more cost effective alternative, outsourcing has become an extremely popular modern business development. Once thought of as an alternative for only large multinational corporations (Sharpe, 1997), outsourcing has now evolved into a viable business solution for any organization serious about improving its market position, reducing costs, and improving overall quality (Burden et al., 2006). While many corporate The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/0025-1747.htm

- 53. Outsourced marketing 895 Management Decision Vol. 47 No. 6, 2009 pp. 895-918 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited 0025-1747 DOI 10.1108/00251740910966640 activities such as information technology (IT) and human resource management (HRM) have traditionally been performed “in-house”, advocacy for outsourcing the bulk of these efforts is steadily increasing (Klaas et al., 2001) and more and more they are becoming a global business trend (Leverett et al., 2004). Outsourcing refers to a contractual relationship for the provision of business services by an external provider [. . .] in other words – a company pays another company to do some work for it (Belcourt, 2006, p. 269). Simply put, outsourcing is turning over to a supplier those activities outside the organization’s chosen core competencies (Sharpe, 1997). Advocates of outsourcing argue that the practice can reduce costs, increase service quality by producing greater

- 54. economies of scale, increase incentives and accountability for service providers, and increase access to experts in specialized areas (cf. Greaver, 1999; Hendry, 1995; Laugen et al., 2005; Mowery et al., 1996; Rimmer, 1991; Uttley, 1993). Despite these suggested benefits, others claim that hiring an outside agency to do the “right-brain” (McGovern and Quelch, 2005, p. 1) work of internal employees may lead to disharmony, distrust, and diminished employee commitment levels (e.g. Bhagwati et al., 2004; Cox, 1996; Kessler et al., 1999; Lei and Hitt, 1995). A firm’s management must therefore be cognizant of these potential tradeoffs when entertaining the idea of outsourcing. As such, senior management must identify the best marketers with the best vision for the product while simultaneously attending to any consequences that may result. The purpose of this article was to explore the aforementioned idea within the intercollegiate marketing context. Using a mixed-methods research design, the researchers sought to examine the issues, antecedents, and empirical consequences associated with outsourcing among university rights holders[1] and intercollegiate marketing department employees. The following section discusses the antecedents, theoretical underpinnings, and scope of the decision to outsource, in terms of both the progression of collegiate marketing practice and strategic implementation approaches. Subsequent sections discuss the consequences (based on the

- 55. empirical findings), the various implications, and boundary conditions of outsourcing for university athletic departments. Outsourced operations As a reflection of outsourcing as the natural progression of business (see Embleton and Wright, 1998), the outsourcing of sports marketing rights and operations is now common practice among university athletic departments. According to Li and Burden (2002), more than half of the NCAA Division I athletic programs have outsourced some or all of their marketing efforts. The primary reason for this seemingly “mass-undertaking” has been due to the increased complexity and dynamics of the college athletic environment. Further, the various operational and strategic advantages (e.g. core competency foci) that may accrue are particularly attractive to financially struggling university athletic programs. From a general HRM perspective, there are innumerable areas that can be outsourced (see Belcourt, 2006; Goldfarb and Naasz, 1995; Klaas et al., 2001). Within university athletic departments and equally large number of their operations can also be outsourced. Radio game broadcast, call-in shows, game day programs, website production/management, sale of media advertising and venue signage, and sale of “official sponsorship” rights to MD

- 56. 47,6 896 corporations, for example, can all be performed by a qualified outside agency (Burden and Li, 2002). Outsourcing the aforementioned areas provides the athletic department with a chance to work with experts who can offer a professional and objective viewpoint in many areas (e.g. Belcourt, 2006; Burden and Li, 2002). Likewise, it allows them to gain new knowledge, access new markets, establish traction in the industry, reduce the threats and barriers of competition, enhance resource efficiency, and acquire new skills (Klaas et al., 2001). Outsourcing can also free up valuable resources that, in turn, allow for crucial resource reallocation toward core business activities to better serve organizational goals (Burden and Li, 2005), while providing greater access to leading-edge technology and limiting the focus to core competencies (Harris et al., 1998). Informing this strategic management process is that of core competencies theory (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990). This theory suggests that certain business activities should be performed either in house or by suppliers. While some have sought to operationalize the concept formally (e.g. Gallon et al., 1995; Henderson and Cockburn,

- 57. 1994), for our purposes the most important aspect of core competence is its popular encapsulation of an emerging and increasingly influential approach to strategic management. Hence, we refer to core competencies as activities beyond the scope of the marketing staff that should be considered for outsourcing, which, if performed to the expected level, have the ability to deliver a competitive advantage to the athletic department. Hence, in this context, the key feature of core competencies is the focus on organizational knowledge rather than decision-making processes as the engine of competitive performance (Scarbrough, 1998). Therefore, the primary impetus for outsourcing is strategic to build a competitive advantage based on financial considerations and streamlining other operational areas (Belcourt, 2006). From a human resources perspective, the potential for increasing staff size without adding new individuals to the payroll is both financially attractive and operationally viable for many athletic departments. Within this context, though, McKindra (2005) and Johnson (2005) noted that the promise of considerable financial return may serve as the primary thrust to outsource some component of the marketing department’s operations. Burden and Li’s (2003, 2004) articles provided evidence for the importance of such factors as annual operating budgets and total expenses for men’s teams, particularly amongst

- 58. programs with large budgets. Given all of the aforementioned positives for outsourcing, it is clear that this decision is a critical tool for attaining and fostering a competitive (albeit financial) edge amongst intercollegiate athletic departments. In light of the evidence to support outsourcing (see Burden et al., 2006), many researchers still question why institutions decide to formulate such partnerships. For some organizations experienced with outsourcing, there are hints that the process is not all that cost-effective or moreover problem-free (cf. Rochester and Douglas, 1990, Lacity and Hirschheim, 1993). Research has indicated the majority of respondents found it was more expensive to manage the outsourced activity than originally expected and in several cases, service levels were not nearly as high as anticipated (cf. Albertson, 2000; Lacity and Willcocks, 1996; Lacity et al., 1995). Thus, for some institutions there are potential downfalls to outsourced operations. The degrading of marketing services, biased business dealings, a lack of management input, loss of departmental control, and problems related to selecting the right service provider have Outsourced marketing 897

- 59. all been forwarded as consequences of the practice (Burden and Li, 2005). Ultimately, by becoming dependent on the outsourcing agency, the existing marketing department’s climate, skills, and relationships may become severely strained, thereby leading to organizational disharmony. As Belcourt (2006) noted, outsourcing alienates and “deskills” employees which can lead to the disintegration of an organization’s culture through diminished employee commitment. Agency theory and the communicative partnership The partnership between an athletic program and a rights holder is the most crucial factor in ensuring that the outsourced partnership will be successful (Burden and Li, 2002). A well-thought out strategic plan (long-term considerations) followed with the support from the institutional hierarchy is critical to achieving desired outcomes (Burden et al., 2006). Top managers (in the case of college athletics, the Athletic Director) will decide what areas to concentrate on (based on what the department does best – competencies), and contract everything else out to outside vendors (Belcourt, 2006). Therefore, core functions or competencies are in fact the real source of competitive advantage as the administration’s ability to consolidate skills and technologies allows for greater flexibility and improved organizational efficiency (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990).

- 60. From an agency theory perspective, a problem occurs when two parties have different goals and labor is divided (Eisenhardt, 1989). One party, the principal (i.e. the customer or outsourcing user) delegates work to another, the agent (i.e. the provider) who performs the work. Agency theory uses the “contract metaphor” to help describe this relationship. Agency costs include the costs of structuring, monitoring, and bonding a set of contracts among agents and principals with conflicting interests. They also include the value of output lost when the cost of enforcing the contracts exceeds the benefits of the contracts (Logan, 2000). Eisenhardt (1985) remarked that agency theory is concerned with resolving two problems that can occur in agency relationships. The first is when the desires or goals of the principal and agent conflict and it is difficult or expensive for the principal to verify what the agent is actually doing. The second is the problem of risk sharing that arises when the principal and agent have different risk preferences. Thus, McKindra (2005) and Burden et al. (2006) both posited that in order to properly facilitate this agency/provider relationship, a strategic balance point between the university’s organizational mission and the rights holder’s mission must be maintained. As such, many schools and rights holders have worked to create various partnerships with other corporate sponsors that target appealing experiences for the student-athletes, fans, and alumni.

- 61. In order to successfully implement these experiences, risk sharing, communication, and above all verification of objectives between key all of the “key players” is paramount. Everyone involved in the partnership needs to regularly and clearly communicate particularly in terms of turnaround time, risk, and debt (cf. Fisher, 2003; Mohr and Spekman, 1994). Given the difficulties of behavior-based contracts suggested by agency theory, it is reasonable to assume that the overwhelming majority of clients would insist on outcome-based contracts when acquiring marketing services. Such a strategy can only succeed if the client can confidently specify current and future requirements (i.e. communicate them accurately). As Embleton and Wright (1998) contended, there are two main areas that have to be addressed when outsourcing – the foremost of which is MD 47,6 898 communication. These authors found that nearly 80 percent of employees will initially view outsourcing negatively. Hence, benefits to an outsourcing partnership will only accrue if active planning and communication take precedent (cf. Fisher, 2003; Mohr and

- 62. Spekman, 1994), particularly in terms of specific marketing channels (Mohr and Nevin, 1990) but moreover, interfirm relationships (Mohr et al., 1996). Therefore, the AD, the University President, the marketing employees, and the rights holders will need to establish healthy communication lines for the partnership to be successful and more importantly, implication free. Study 1 As highlighted above, athletic programs are becoming increasingly reliant on external providers for a number of services. The purpose of this article was to explore the aforementioned idea within the intercollegiate marketing context. Using a mixed-methods research design, the researchers sought to examine the issues, antecedents, and empirical consequences associated with outsourcing among university rights holders and intercollegiate marketing department employees. The following section discusses the antecedents and scope of the decision to outsource, in terms of both the progression of collegiate marketing practice and underpinning reasons. Subsequent sections discuss the consequences (based on the empirical findings), the various implications, and boundary conditions of outsourcing for university athletic departments. The working environment For this initial phase of the study, the conference under examination consisted of

- 63. NCAA Division I-A institutions who have all fully embraced the outsourcing option. Currently, there are numerous right holders who conduct (in part or all) of the respective department’s marketing operations. Within this dynamic, the Marketing Director serves as the facilitator, initiating the directives of the rights holder in addition to providing valuable reciprocal input to the agency. However, the Marketing Director also initiates his/her own programs based on what the outsourcing agency is or is not contracted to do. The Marketing Director maintains a staff (sizes vary based on the number of operations outsourced) composed of Assistant Marketing Directors, graduate students, and interns who all serve the department in various capacities. Thus, Marketing Directors are the “ring-masters” (McGovern and Quelch, 2005, p. 2) who help to develop and monitor this integrated network of outside suppliers and internal employees to create both immediate and long-term value for the athletic department. Methods Procedure. As noted by Glesne (2006), focus group research is useful in studies that are exploratory in nature. Consistent with the purpose of Study 1, the researchers conducted semi-structured focus group interviews with marketing directors housed within one Division I-A intercollegiate conference. Of this census sample, all 16 Marketing Directors (eight female, eight male) within the

- 64. conference were contacted prior to the interview date, informed of the purpose of our inquiry, and asked to voluntarily participate. All 16 Marketing Directors agreed to take part and have their discussion audio recorded. The focus group facilitator guided the conversation-style Outsourced marketing 899 interviewing with “talking points” surrounding the topic of rights holders and departmental marketing operations. Sample talking points included: “concerns of working with rights holders”, “improving satisfaction in the relationship between rights holders and the marketing department”, and “identifying/aligning the priorities of the rights holders and the marketing department”. The focus group interview was approximately one hour in length, was audio-recorded, and subsequently transcribed verbatim. Morgan and Spanish (1984) identify focus group as an advantageous research tool well-suited to both precede and triangulate data collected using several other methodologies. Operating from this rationale, we followed up our focus group interview by sending a series of open-ended questions to each

- 65. marketing director one week after the initial focus group interview was conducted. These questions allowed each Marketing Director to discuss the emergent themes from the focus group within his or her respective athletic departments. Thus, coupled with the focus group data, this latter stage was implemented as a means to sharpen the definitions and properties of the emergent concepts. Sample questions included: “How long has your marketing department been with the current rights holder?”, “How satisfied are you with the relationship that your marketing department has with the rights holders?”, and “What do you think could promote a better relationship with your rights holders?”. Responses were compiled and analyzed as described below. Analysis. The researchers adopted a “grounded, a posteriori, inductive, context-sensitive scheme” (Schwandt, 2007, p. 32) approach to analyze all the data. Specifically, two members of the research team utilized the method of constant comparison, whereby the data were coded and analyzed simultaneously to develop an understanding of emergent concepts and their relationships (Glaser, 1965). The sequencing of the data collection led the researchers to first code the interview data for the initial categories. Both researchers coded the transcripts individually and then met to discuss any opposing or divergent views. Upon reconciling these discrepancies the researchers then compared initial categories with the responses

- 66. from the follow-up questions. As with the focus group data, comparisons were first performed individually and then jointly by two members of the research team as a means to refine emergent themes. Results and discussion Two primary themes emerged from the focus group and interview data: (1) control; and (2) communication. Firstly, however, and closely mirroring that of previous literature (Burden and Li, 2002, 2003), the data from Study 1 revealed that marketing directors perceived outsourcing as crucial in providing revenue for the athletic department and allowed for enhanced promotions and coverage of athletic events. Most marketing directors were generally satisfied with their current rights holder and felt that it would be in the best interest of the athletic department to continue the relationship. Despite these positive feelings, the directors also expressed some frustration and dissatisfaction with their current rights holders. Specifically, there emerged a perceived lack of control that prevented them from fully addressing the needs of their respective programs. Subsequently, it was MD 47,6

- 67. 900 supposed that the needs of the rights holders were not always being met and the majority of the directors felt that there existed an “us against them” dichotomy which impeded departmental progress. Overwhelmingly, the marketing directors felt that the primary “solution” to the above-mentioned frustration was to improve the communication between the marketing department and rights holders (see also Li and Burden, 2002). Therefore, communication was selected as the factor most important to the analyses. Despite the integral role of communication in this dynamic, most marketing directors expressed dissatisfaction with the level, frequency, and direction of the existing communication – a finding previously absent from the literature. In line with this finding, research on the management of relationships has increasingly focused on channel communication as a central tenet to effective organizational functioning (cf. Gastpar et al., 2003; Mohr and Nevin, 1990). In particular, these communicative behaviors between channel members have been linked to trust (Anderson and Narus, 1990), coordination (Guiltinan et al., 1980), and especially commitment (cf. Anderson and Weitz, 1986; Morgan and Hunt,

- 68. 1994). Given this line of research and the popularity of outsourcing in terms of the identifiable benefits (e.g. additional revenue, streamlining HRM, and core competencies), this result led the authors to ask some important additional questions: . Could dissatisfaction with communication result in a level of frustration that may lead to unintended outcomes among the internal employees? . Could the employees’ commitment to their department/organization be affected as result of outsourcing? Study 2 Based on the initial exploratory results compiled in Study 1, a questionnaire was constructed in order to examine whether the qualitative findings support the general contention that lack of communication between rights holders and the collegiate marketing department may result in unintended outcomes. Specifically, the authors argue that communication satisfaction may likely be an inhibitor to the marketing employees’ commitment (see Figure 1). These arguments are based on the aforementioned “dichotomized” relationship and the literature suggesting negative consequences of the practice (cf. Albertson, 2000; Bhagwati et al., 2004; Burden and Li, 2005; Cox, 1996; Lei and Hitt, 1995; Kessler et al., 1999). In addition, it has often been