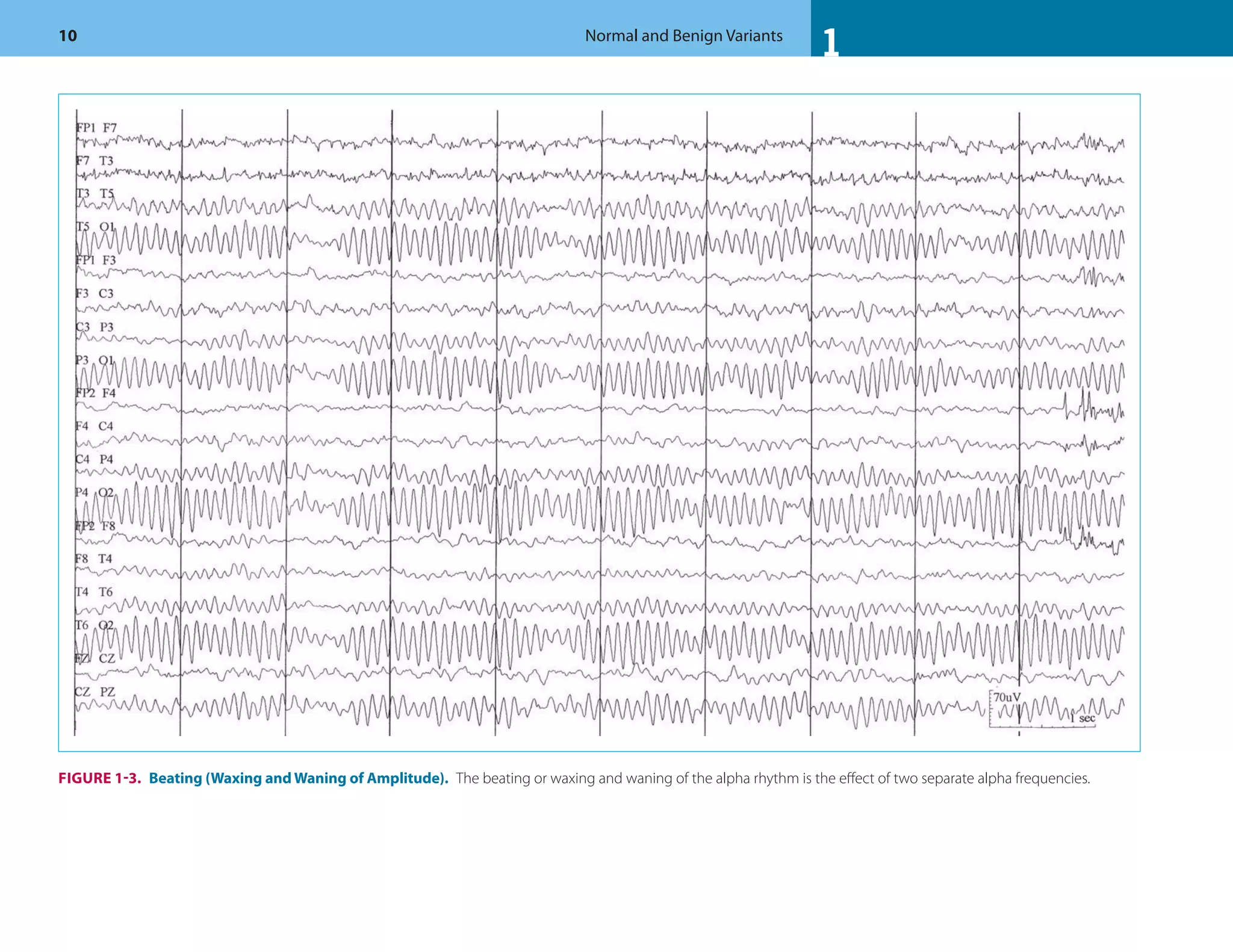

This document discusses normal features and variants of the alpha rhythm seen on EEG. Key points include:

- Alpha rhythm is an 8-13 Hz rhythm seen over the occipital regions with eyes closed that attenuates with eye opening.

- Features like frequency, voltage, regulation, distribution and asymmetry are described for normal alpha rhythm in children and adults.

- Variants including central/temporal alpha and prominent frontal alpha are discussed.

- Parameters outside of normal ranges like abnormal frequency, low voltage, and persistent asymmetry are considered abnormal.

![1

1 Normal and Benign Variants 123

References

1. Storm V, Bekkering D. Some results obtained with the

EEG-spectrograph. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol.

1958;10(3):563.

2. Gloor P. Contributions of electroencephalography and

electrocorticography to the neurosurgical treatment of

the epilepsies. Adv Neurol. 1975;8:59.

3. Sperling M. Intracranial electroencephalography. In:

Ebersole J, Pedley T, eds. Current Practice of Clinical

Electroencephalography. Philadelphia: Lippincott

Williams & Wilkins. 2003

4. Goodwin J. The significance of alpha variants in the

EEG, and their relationship to an epileptiform syndrome.

Am J Psychiatry. 1947;104(6):369–379.

5. Aird RB, Gastaut Y. Occipital and posterior

electroencephalographic rhythms. Electroencephalogr

Clin Neurophysiol. 1959;11:637–756.

6. Chatrian GE (Chairman), Bergamini L, Dondey M,

Klass DW, Lennox-Buchthal M and Petersén I. A

glossary of terms most commonly used by clinical

electroencephalographers. Electroencephalogr Clin

Neurophysiol. 1974;37:538–548.

7. Adams A. Studies on the flat electroencephalogram

in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol.

1959;11(1):35–41.

8. Gibbs FA, Gibbs EL. Atlas of Electroencephalography.

Cambridge, MA: Addison Wesley; 1950.

9. Niedermeyer E. The normal EEG of the waking

adult. In: Niedermeyer E, Da Silva F, eds.

Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical

Applications, and Related Fields. Philadelphia:

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005.

10. Eeg-Olofsson O, Petersen I, Sellden U. The development

of the electroencephalogram in normal children from

the age of 1 through 15 years. Paroxysmal activity.

Neuropadiatrie. 1971;2(4):375–404.

11. Petersen I, Eeg-Olofsson O. The development of the

electroencephalogram in normal children from the

age of 1 through 15 years. Non-paroxysmal activity.

Neuropadiatrie. 1971;2(3):247–304.

12. Kellaway P. Overly approach to visual analysis: Element

of the normal EEG and their characteristics in children

and adults. In: Ebersole JS, Pedley TA (eds) Current

Practice of Clinical Electroencephalography. 3rd ed.

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA,

2003;100–159.

13. Sunku A, Donat JF, Johnston JA, et al. Occipital

responses to visual pattern stimulation: B104. J Clin

Neurophysiol. 1996;13(5):438.

14. Westmoreland B. Electroencephalography: adult, normal,

and benign variants. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;4(1):119.

15. Fisch BJ. Fisch and Spehlmann's EEG Primer: Basic

Principles of Digital and Analog EEG. New Orleans:

Elsevier Science Health Science Divison. 1999

16. Gronseth G, Greenberg M. The utility of the

electroencephalogram in the evaluation of patients

presenting with headache: a review of the literature.

Neurology. 1995;45(7):1263.

17. Raieli V, Puma D, Brighina F. Role of neurophysiology

in the clinical practice of primary pediatric headaches.

Drug Dev Res. 2007;68(7).

18. Grey Walter W, Shipton H. A new toposcopic display

system. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol.

1951;3(3):281–292.

19. Gibbs EL, Gibbs FA. [Electroencephalogram in

congenital anophthalmia (author's transl)]. EEG EMG

Z Elektroenzephalogr Elektromyogr Verwandte Geb.

1981;12(4):171–173.

20. Niedermeyer E. Sleep and EEG. In: Niedermeyer E,

Da Silva F, eds. Electroencephalography: Basic Principles,

Clinical Applications, and Related Fields. 5th ed.

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005;

193–207.

21. Hughes J. EEG in Clinical Practice. Burlington, MA,

USA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1994.

22. Dan B, Boyd SG. A neurophysiological perspective

on sleep and its maturation. Dev Med Child Neurol.

2006;48(09):773–779.

23. Hughes JR. Sleep spindles revisited. J Clin Neurophysiol.

1985;2(1):37–44.

24. Hess R. The electroencephalogram in sleep.

Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1964;16(1):44–55.

25. Dreyfus-Brisac and Curzi-Dascalova, 1975. Dreyfus-

Brisac C and Curzi-Dascalova L, The EEG during the

first year of life. In: G.C. Lairy, Editor, Handbook of

electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology,

Elsevier, Amsterdam (1975), pp. 6–23.

26. Tharp B, Aminoff M. Electrodiagnosis in Clinical

Neurology. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1980.

27. Fois A. The electroencephalogram of the normal child.

Springfield: Thomas; 1961:111.

28. Brandt S, Brandt H. The electroencephalographic

patterns in young healthy children from 0 to five

years of age; their practical use in daily clinical

electroencephalography. Acta Psychiatrica et Neurologica

Scandinavica. 1955;30(1–2):77.

29. Gibbs F, Gibbs E. Atlas of Electroencephalography.

Cambridge, MA: Addison Wesley, 1952.

30. Oswald I. Sudden bodily jerks on falling asleep. Brain.

1959;82(1):92–103.

31. Fusco L, Pachatz C, Cusmai R, Vigevano F. Repetitive

sleep starts in neurologically impaired children: an

unusual non-epileptic manifestation in otherwise

epileptic subjects. Epileptic Disord. 1999;1:63–67.

32. Fusco L, Specchio N. Non-epileptic paroxysmal

manifestations during sleep in infancy and childhood.

Neurol Sci. 2005;26:205–209.

33. Schwartz S, Gallagher R, Berkson G. Normal repetitive

and abnormal stereotyped behavior of nonretarded

infants and young mentally retarded children. Am J Ment

Def. 1986;90(6):625.

34. Sheldon S. Parasomnias in childhood. Pediatr Clin North

Am. 2004;51(1):69–88.

35. Westmoreland B. Benign electroencephalographic

variants and patterns of uncertain clinical significance.

In: Ebersole JS, Pedley TA (eds) Current Practice of

Clinical Electroencephalography. 3rd ed. Philadelphia:

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, USA, 2003

36. Eeg-Olofsson O. The development of the

electroencephalogram in normal adolescents from the age

of 16 through 21 years. Neuropadiatrie. 1971;3(1):11–45.

37. Cavazzuti G, Cappella L, Nalin A. Longitudinal study of

epileptiform EEG patterns in normal children. Epilepsia.

2007;21(1):43–55.

38. Heijbel J, Blom S, Rasmuson M. Benign epilepsy of

childhood with centrotemporal EEG foci: a genetic study.

Epilepsia. 200;16(2):285–293.

39. Degen R, Degen H. Some genetic aspects of rolandic

epilepsy: waking and sleep EEGs in siblings. Epilepsia.

2007;31(6):795–801.

40. Dalla Bernardina B, Beghini G, Tassinari C. Rolandic

spikes in children with and without epilepsy (20 subjects

polygraphically studied during sleep). Epilepsia.

2007;17(2):161–167.

41. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and

statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington

(DC): American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

42. The, M., A 14-month randomised clinical trial of

treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1073–1086.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atlasofpediatriceeg-230702062942-5219ce2c/75/Atlas-of-Pediatric-EEG-pdf-136-2048.jpg)

![4 Focal Nonepileptoform Activity 387

41. Lewis D. Febrile convulsions and mesial temporal

sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 1999;12(2):197.

42. Raymond AA, Fish DR, Sisodiya SM, Alsanjari N,

Stevens JM, Shorvon SD. Abnormalities of gyration,

heterotopias, tuberous sclerosis, focal cortical dysplasia,

microdysgenesis, dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial

tumour and dysgenesis of the archicortex in epilepsy:

clinical, EEG and neuroimaging features in 100 adult

patients [Review]. Brain. 1995a;118:629–660.

43. Raymond AA, Fish DR. EEG features of focal

malformations of cortical development. J Clin

Neurophysiol. 1996;13:495–506.

44. Pesola GR, Westfal RE. New-onset generalized seizures

in patients with AIDS presenting to an emergency

department. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(9):905–911.

45. Gabuzda DH, Levy SR, Chiappa KH.

Electroencephalography in AIDS and AIDS-related

complex. Clin Electroencephalogr. 1988;19(1):1–6.

46. Frantzen E, Lennox-Buchthal M, Nygaard A.

Longitudinal EEG and clinical study of children with

febrile convulsions. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol.

1968;24(3):197.

47. Blume WT, Kaibara M. Atlas of Pediatric

Encephalography. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott-

Raven; 1999.

48. Wang PJ, Hwu WL, Shen YZ. Epileptic seizures

and electroencephalographic evolution in genetic

leukodystrophies. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18(1):

25–32.

49. Pampiglione G, Lehovsky M. The evolution of EEG

features in 26 children with proven neuronal lipidosis.

Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1968;25(5):509.

50. Dumermuth G, Walz W, Scollo-Lavizzari G, Kleiner B.

Spectral analysis of EEG activity in different sleep stages

in normal adults. Eur Neurol. 1972;7(5):265–296.

51. Balslev T, et al. Recurrent seizures in metachromatic

leukodystrophy. Pediatr Neurol. 1997;17(2):150.

52. Marchioni E, et al. Familial hemiplegic migraine versus

migraine with prolonged aura: an uncertain diagnosis in

a family report. Neurology. 1995;45(1):33–37.

53. Farkas V, et al. The EEG background activity in children

with migraine. Cephalalgia. 1987;7(suppl 6):59–64.

54. Sand T. EEG in migraine: a review of the literature. Funct

Neurol. 1991;6(1):7–22.

55. Gastaut JL, Yermenos E, Bonnefoy M, Cros D. Familial

hemiplegic migraine: EEG and CT scan study of two

cases. Ann Neurol. 1981;10:392–395.

56. Schoenen J. Clinical neurophysiology of headache.

Neurol Clin. 1997;15(1):85–105.

57. Beaumanoir A, Jekiel M. Electrographic Observations

during Attacks of Classical Migraine. Migraine and

Epilepsy. London: Butterworth Heinemann; 1987.

11: p. 163–80.

58. Gorman MJ, Welch KMA. Cerebral blood flow and

migraine. 1993, The Regulation of Cerebral Blood Flow.

Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

59. Niedermeyer E. The EEG in patients with migraine and

other forms of headache. In: Niedermeyer EdS, Fernando

Lopes, eds. Electroencephalography: Basic principles,

Clinical Applications, and Related fields. Philadelphia:

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:631–638.

60. Vahedi K, Denier C, Ducros A, Bousson V, Levy C,

Chabriat H, Haguenau M, Tournier-Lasserve E, Bousser

MG: CACNA1A gene de novo mutation causing

hemiplegic migraine, coma, and cerebellar atrophy.

Neurology 2000;55:1040–1042.

61. Spadaro M, et al. A G301R Na+/K+-ATPase mutation

causes familial hemiplegic migraine type 2 with

cerebellar signs. Neurogenetics. 2004;5(3):177–185.

62. Cevoli S, et al. Familial hemiplegic migraine: clinical

features and probable linkage to chromosome 1 in an

Italian family. Neurol Sci. 2002;23(1):7–10.

63. Carrera P, Piatti M, Stenirri S, et al. Genetic heterogeneity

in Italian families with familial hemiplegic migraine.

Neurology. 1999;53:26–33.

64. O'Brien MJ, Lems YL, Prechtl HF. Transient flattenings

in the EEG of newborns––a benign variation.

Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1987;67(1):16–26.

65. Challamel MJ, Isnard H, Brunon AM, Revol M.

Transitory EEG asymmetry at the start of quiet sleep

in the newborn infant: 75 cases. Rev Electroencephalogr

Neurophysiol Clin. 1984;14(1):17–23.

66. Hrachovy RA, Mizrahi EM, Kellaway P.

Electroencephalography of the newborn. In:

Daly D, Pedley T, eds. Current Practice of Clinical

Electroencephalography. New York: Lippincott Williams

& Wilkins; 1990:201.

67. Lagerlund TD, Daube JR, Rubin DI. Volume conduction.

In: Daube JRR, Devon I, eds. Clinical Neurophysiology.

New York: Oxford University Press; 2009:33–52.

68. Markand ON, Pearls, perils, and pitfalls in the use of

the electroencephalogram. Semin Neurol. 2003;23(1):7–46.

69. Barkovich AJ, Norman D. Absence of the septum

pellucidum: a useful sign in the diagnosis of

congenital brain malformations. Am J Roentgenol.

1989;152(2):353–360.

70. Iinuma K, Handa I, Kojima A, Hayamizu S, Karahashi

M. Hydranencephaly and maximal hydrocephalus:

usefulness of electrophysiological studies for their

differentiation. J Child Neurol. 1989;4:114–117.

71. Tayama M, Hashimoto T, Mori K, Miyazaki M,

Hamaguchi H, Kuroda Y, et al. Electrophysiological study

on hydranencephaly. Brain Dev. 1992;14(3):185.

72. Lott IT, McPherson DL, Starr A. Cerebral cortical

contributions to sensory evoked potentials:

hydranencephaly. Electroencephalogr Clinl Neurophysiol.

1986;64(3):218–223.

73. Neville BGR. The origin of infantile spasms: evidence

from a case of hydranencephaly. Dev Med Child Neurol.

1972;14(5):644–647.

74. Ferguson JH, Levinsohn MW, Derakshan I. Brainstem

seizures in hydranencephaly. Neurology. 1974;24(12):1152.

75. Velasco M, Velasco F, Gardea G, Gordillo F, Diaz de

Leon AE. Polygraphic characterization of the sleep-

epilepsy patterns in a hydranencephalic child with severe

generalized seizures of the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

Arch Med Res. 1997;28:297–302.

76. Chatrian GE, Shaw CM, Leffman H. The significance

of periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges in EEG:

an electrographic, clinical and pathological study.

Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1964;17:177–193.

77. Hughes JR. EEG in Clinical Practice. Burlington, MA:

Butterworth-Heinemann Boston; 1994.

78. Raroque HG, Jr., Purdy P. Lesion localization in periodic

lateralized epileptiform discharges: gray or white matter.

Epilepsia. 1995;36(1):58–62.

79. Westmoreland BF, Klass DW, Sharbrough FW. Chronic

periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges. Arch Neurol.

1986;43(5):494–496.

80. Garcia-Morales I, Garcia MT, Galan-Davila L, Gomez-

Escalonilla C, Saiz-Diaz R, Martinez-Salio A, de la

Pena P, Tejerina JA. Periodic lateralized epileptiform

discharges: etiology, clinical aspects, seizures, and

evolution in 130 patients. J Clin Neurophysiol.

2002;19:172–177.

81. Fitzpatrick W, Lowry N. PLEDs: clinical correlates.

Can J Neurol Sci. 2007;34(4):443–450.

82. Gross DW, Gotman J, Quesney LF, Dubeau F, Olivier A.

Intracranial EEG with very low frequency activity fails to

demonstrate an advantage over conventional recordings.

Epilepsia. 1999; 40: 891–898.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atlasofpediatriceeg-230702062942-5219ce2c/75/Atlas-of-Pediatric-EEG-pdf-400-2048.jpg)

![4

388 Focal Nonepileptoform Activity

83. Garcia-Morales I, Garcia MT, Galan-Davila L, Gomez-

Escalonilla C, Saiz-Diaz R, Martinez-Salio A, de la

Pena P, Tejerina JA. Periodic lateralized epileptiform

discharges: etiology, clinical aspects, seizures, and

evolution in 130 patients. J Clin Neurophysiol.

2002;19:172–177.

84. Noetzel M, Blake J. Seizures in children with congenital

hydrocephalus: long-term outcome. Neurology.

1992;42(7):1277.

85. Graebner R, Celesia G. EEG findings in hydrocephalus

and their relation to shunting procedures.

Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1973;35(5):517.

86. Liguori G, Abate S, Buono S. Pittore L. EEG findings in

shunted hydrocephalic patients with epileptic seizures.

Ital J Neurol Sci. 1986;7(2):243–247.

87. Veggiotti P, Beccaria F, Guerrini R, Capovilla G,

Lanzi G. Continuous spike-and-wave activity during

slow-wavesleep: syndrome or EEG pattern? Epilepsia.

1999;40:1593–601.

88. Sato O, Yamaguchi T, Kittaka M, Toyama H,

Hydrocephalus and epilepsy. Childs Nerv Syst.

2001;17:76–86

89. Klepper J, Buesse M, Strassburg HM, et al: Epilepsy

in shunt treated hydrocephalus. Dev Med Child

Neurol 1998;40:731–736.

90. Arzimanoglou AA, Andermann F, Aicardi J, Sainte-

Rose C, Beaulieu MA, Villemure JG, et al. Sturge-Weber

syndrome: indications and results of surgery in 20

patients. Neurology. 2000;55:1472–1479.

91. Jan MM, Sadler M, Rahey SR. Lateralized postictal

EEG delta predicts the side of seizure surgery in

temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42(3):402–405.

92. Menkes J, Maria B. Neurocutaneous syndromes. In:

Menkes J, Maria B, Sarnat HB, eds. Child Neurology. 7th ed.

Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams-Wilkins; 2006:803–828.

93. Chien LT, Boehm RM, Robinson H, et al. Characteristic

early electroencephalographic changes in herpes simplex

encephalitis, Arch Neurol. 1977;34:361–364.

94. Lai CW, Gragasin ME. Electroencephalography in

herpes simplex encephalitis. J Clin Neurophysiol.

1988;5(1):87.

95. Westmoreland BF. The EEG in cerebral in ammatory

processes. In: Niedermeyer E, Da Silva F, eds.

Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical

Applications, and Related Fields. Philadelphia: Lippincott

Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

96. Whitley R, Kimberlin D. Viral encephalitis. Pediatr Rev.

1999;20(6):192–198.

97. Whitley R, Kimberlin D. Herpes Simplex: Encephalitis

Children and Adolescents. Elsevier; 2005.

98. Arfel G, Fischgold H. EEG-signs in tumours of the

brain. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1961;19:

36–50.

99. Goldensohn ES (1979a): Use of EEG for evaluation of

focal intracranial lesions. In: Klass DW, Daly DD, eds.

Current Practice of Clinical Electroencephalography.

New York: Raven Press; 1979a:307–341.

100. Raymond AA, Fish DR, Boyd SG, Smith SJ, Pitt MC,

Kendall B. Cortical dysgenesis: serial EEG findings

in children and adults. Electroencephalogr Clin

Neurophysiol. 1995b;94:389–397.

101. Gloor P, Ball G, Schaul N. Brain lesions that produce

delta waves in the EEG. Neurology. 1977;27(4):

326–333.

102. Sharbrough FW, Nonspecific abnormal EEG patterns. In:

Niedermeyer E, Da Silva F, eds. Electroencephalography:

Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields.

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:

235–254.

103. Di Gennaro G, Quarato PP, Onorati P, Colazza GB,

Mari F, Grammaldo LG, Ciccarelli O, et al. Localizing

significance of temporal intermittent rhythmic delta

activity (TIRDA) in drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Clin

Neurophysiol. 2003 114:70–78.

104. Geyer JD, Bilir E, Faught RE, et al. Significance of

interictal temporal lobe delta activity for localization

of the primary epileptogenic region [see comment].

Neurology. 1999;52:202–205.

105. Normand MM, Wszolek ZK, Klass DW.

Temporal intermittent rhythmic delta activity

in electroencephalograms. J Clin Neurophysiol.

1995;12(3):280–284.

106. Reiher J, Beaudry M, Leduc CP. Temporal intermittent

rhythmic delta activity (TIRDA) in the diagnosis of

complex partial epilepsy: sensitivity, specificity and

predictive value. Can J Neurol Sci. 1989;16(4):

398–401.

107. Cobb WA, Guiloff RJ, Cast J. Breach rhythm: the

EEG related to skull defects. Electroencephalogr Clin

Neurophysiol. 1979;47(3):251–271.

108. Jaffe R, Jacobs L. The beta focus: it's nature and

significance. Acta Neurol Scand. 1972;48(2):191–203.

109. Kershman J, Conde A, Gibson WC.

Electroencephalography in differential diagnosis

of supratentorial tumors. Arch Neurol Psychiatry.

1949;62(3):255.

110. Palmini A, Gambardella A, Andermann F, et al. Intrinsic

epileptogenicity of human dysplastic cortex as suggested

by corticography and surgical results. Ann Neurol.

1995;37:476–487.

111. Taylor DFM, Bruton C, Corsellis J. Focal dysplasia of the

cerebral cortex in epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.

1971;34:369–387.

112. Quirk JA, Kendall B, Kingsley DPE, et al. EEG features

of cortical dysplasia in children. Neuropediatrics.

1993;24:193–199.

113. Blume WT, David RB, Gomez MR. Generalized

sharp and slow wave complexes. Associated clinical

features and long-term follow-up. Brain. 1973;96(2):

289–306.

114. Green RL, Wilson WP. Asymmetries of beta activity

in epilepsy, brain tumor, and cerebrovascular

disease. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol.

1961;13:75–78.

115. Barkovich A, Kuzniecky R, Bollen A, Grant P. Focal

transmantle dysplasia: a specific malformation of cortical

development. Neurology. 1997;49:1148–1152.

116. Sullivan LR, Kull LL, Sweeney DB, Davis CP.

Cortical dysplasia: zones of epileptogenesis. Am J

Electroneurodiagnostic Technol. 2005;45:49–60.

117. Ambrosetto G. Treatable partial epilepsy and unilateral

opercular neuronal migration disorder. Epilepsia.

1993;34:604–608.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atlasofpediatriceeg-230702062942-5219ce2c/75/Atlas-of-Pediatric-EEG-pdf-401-2048.jpg)

![5

5 Generalized Nonepileptiform Activity 467

References

1. Van Cott A, Brenner R. Drug effects and toxic

encephalopathy. In: Ebersole JS, Pedley TA, eds. Current

Practice of Clinical Electroencephalography. Philadelphia:

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:463–482.

2. Blume WT. Drug effects on EEG. J Clin Neurophysiol.

2006;23(4):306–311.

3. Bauer G, B.R., EEG, drug effects, and central nervous

system poisoning. In: Niedermeyer E, Da Silva FHL,

eds. Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical

Applications, and Related Fields. Amsterdams: Lippincott

Williams & Wilkins. 2005.

4. Kato M, Dobyns W. Lissencephaly and the molecular

basis of neuronal migration. Hum Mol Genet. 2003.

12(90001):89–96.

5. Osborn AG. Diagnostic Imaging: Brain. Salt Lake City,

UT: Amirsys. 2004.

6. Singh R, Gardner RJM, Crossland, KM, et al.

Chromosomal abnormalities and epilepsy: a review

for clinicians and gene hunters. Epilepsia. 2002;43:

127–140.

7. Gastaut H, Pinsard N, Raybaud C, et al. Lissencephaly

(agyria-pachygyria): clinical findings and serial EEG

studies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1987;29:167–180.

8. Worle H, Keimer R, B. Kohler B. [Miller-Dieker syndrome

(type I lissencephaly) with specific EEG changes].

Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 1990;138(9):615–618.

9. De Rijk-van Andel JF, Arts WF, De Weerd AW. EEG

and evoked potentials in a series of 21 patients with

lissencephaly type I. Neuropediatrics. 1992;23(1):4–9.

10. Barkovich A, Lindan C. Congenital cytomegalovirus

infection of the brain: imaging analysis and embryologic

considerations. Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15(4):703–715.

11. Pilz DT, Matsumoto N, Minnerath S, et al. LIS1 and XLIS

(DCX) mutations cause most classical lissencephaly,

but different patterns of malformation. Hum Mol Genet.

1998;7:2029–2037.

12. Dobyns, W.B. et al. Differences in the gyral pattern

distinguish chromosome 17-linked and X-linked

lissencephaly. Neurology. 1999;53:270−277.

13. Guerrini R, Marini C (2006) Genetic malformations of

cortical development. Exp Brain Res 173:322–333

14. Hodgkins PR, Kriss A, Boyd S et al. A study of EEG,

electroretinogram, visual evoked potential, and eye

movements in classical lissencephaly. Dev Med Child

Neurol. 2000;42:48–52.

15. Quirk JA, Kendall B, Kingsley DPE, et al. EEG features

of cortical dysplasia in children. Neuropediatrics.

1993;24:193–199.

16. Bode H, Bubl R. EEG changes in type 1 and type 2

lissencephaly. Klin Pediatr. 1994;206:12–17.

17. Mori K, Hashimoto T, Tayama M, et al. Serial EEG and

sleep polygraphic studies on lissencephaly (agyria–

pachygyria). Brain Dev. 1994;16:365–373.

18. Majkowski J, Lee MH, Kozlowski PB, Haddad R. EEG

and seizure threshold in normal and lissencephalic

ferrets. Brain Res. 1984;307:29–38.

19. Kurlemann G, Schuierer G, Kuchelmeister K, Kleine M,

Weg-lage J, Palm DG. Lissencephaly syndromes: clinical

aspects. Childs Nerv Syst. 1993;9:380–386.

20. De Rijk-van Andel J, Arts W, De Weerd A. EEG

and evoked potentials in a series of 21 patients with

lissencephaly type I. Neuropediatrics. 1992;23(1):4–9.

21. Hakamada S, Watanabe K, Hara K, Miyazaki S. The

evolution of electroencephalographic features in

lissencephaly syndrome. Brain Dev. 1979;4:277–283.

22. Raieli V, Puma D, Brighina F. Role of neurophysiology

in the clinical practice of primary pediatric headaches.

Drug Dev Res. 2007;68(7):389–396.

23. Gronseth GS, Greenberg MK. The utility of the

electroencephalogram in the evaluation of patients

presenting with headache: a review of the literature.

Neurology. 1995;45(7):1263–1267.

24. Doose H. EEG in childhood epilepsy. 1st ed. Montrouge-

France: John Libbey Eurotext. 2003:410.

25. Neubauer BA, Hahn A, Doose H, Tuxhorn I. (2005)

Myoclonic-astatic epilepsy of early childhood—definition,

course, nosography, and genetics. Adv Neurol 95:

147–155.

26. Foletti G, Volanschi D. Influence of lamotrigine addition

on computerized background EEG parameters in

severe epileptogenic encephalopathies. Eur Neurol.

1994;34(1):87–89.

27. Glaze DG. Neurophysiology of Rett syndrome. J Child

Neurol. 2005;20(9):740–746.

28. Niedermeyer E, Rett A, Renner H, Murphy M, Naidu S.

Rett syndrome and the electroencephalogram. Am J Med

Genet Suppl. 1986;1:195–199

29. Walser H, Isler H. Frontal intermittent rhythmic delta

activity, impairment of consciousness and migraine.

Headache J Head Face Pain. 1982;22(2):74–80.

30. Pietrini V, Terzano MG, D’andrea G, Parrino L, Cananzi

AR, Ferro–Milone F. Acute confusional migraine: clinical

and electroencephalographic aspects. Cephalalgia.

1987;7:29–37.6.

31. Gladstein J. Headache in pediatric patients:

diagnosis and treatment. Top Pain Manag. 2007.

22(11):1.

32. Frequin S, Linssen WHJP.1, Pasman JW, Hommes

OR, Merx HL. Recurrent prolonged coma due to basilar

artery migraine. A case report. Headache J Head Face

Pain. 1991;31(2):75–81.

33. Muellbacher W, Mamoli B. Prolonged impaired

consciousness in basilar artery migraine. Headache

J Head Face Pain. 1994;34(5):282–285.

34. Alehan F, Watemberg N. Clinical and laboratory

correlates of frontal intermittent rhythmic delta

activity (FIRDA). Dementia. 2001;9:13.2.

35. Tan HJ, Suganthi C, Dhachayani S, et al. The coexistence

of anxiety and depressive personality traits in migraine.

Singapore Med J. 2007;48:307–310.

36. Fisch BJ. Fisch and Spehlmann's EEG Primer: Basic

Principles of Digital and Analog EEG. Amsterdams:

Elsevier Science Health Science Division. 1999.

37. Sharbrough FW, Nonspecific abnormal EEG

patterns. In: Niedermeyer E, Fernando LDS, eds.

Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical

Applications, and Related Fields. Lippincott Williams &

Wilkins; 2005:235–254.

38. Di Gennaro G, Quarato PP, Onorati P, et al. Localizing

significance of temporal intermittent rhythmic delta

activity (TIRDA) in drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Clin

Neurophysiol. 2003;114:70–78

39. Gullapalli D, Fountain NB. Clinical correlation of

occipital intermittent rhythmic delta activity. J Clin

Neurophysiol. 2003. 20(1):35–41.

40. Riviello J, Foley C. The epileptiform significance of

intermittent rhythmic delta activity in childhood.

J Child Neurol. 1992;7(2):156.

41. Watemberg N, Linder I, Dabby R, Blumkin L, Lerman-

Sagie T. Clinical correlates of occipital intermittent

rhythmic delta activity (OIRDA) in children. Epilepsia.

2007;48:330–334.

42. Belsh J, Chokroverty S, Barabas G. Posterior

rhythmic slow activity in EEG after eye closure.

Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1983;56(6):

562–568.

43. Riviello JJ, Jr., Foley CM. The epileptiform significance

of intermittent rhythmic delta activity in childhood.

J Child Neurol. 1992;7(2):156–160.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atlasofpediatriceeg-230702062942-5219ce2c/75/Atlas-of-Pediatric-EEG-pdf-480-2048.jpg)

![7 Epileptic Encephalopathy 609

using subdural EEG in neocortical epilepsy. Epilepsia.

2006;47:1953–1957.

45. Kobayashi K, Oka M, Akiyama T, et al. Very fast

rhythmic activity on scalp EEG associated with epileptic

spasms. Epilepsia. 2004;45:488–496.

46. Jacobs J, et al. Interictal high-frequency oscillations

(80 500 Hz) are an indicator of seizure onset areas

independent of spikes in the human epileptic brain.

Epilepsia. 2008;49:1893–1907.

47. Bragin A, Jando G, Nadasdy Z, Hetke J, Wise K, Buzsaki

G. Gamma (40–100 Hz) oscillations in the hippocampus

of the behaving rat. J Neurosci. 1995;15:47–60.

48. Staba RJ, Wilson CL, Bragin A, Jhung D, Fried I, Engel

J Jr. High frequency oscillations recorded in human

medial temporal lobe during sleep. Ann Neurol.

2004;56:108–115.

49. Bragin A, Wilson CL, Almajano J, Mody I, Engel J Jr.

High-frequency oscillations after status epilepticus:

epileptogenesis and seizure genesis. Epilepsia.

2004;45:1017–1023.

50. Le Van Quyen M, Khalilov I, Ben-Ari Y. The dark side

of high-frequency oscillations in the developing brain.

Trends Neurosci. 2006;29(7):419–427.

51. Curio G, Mackert BM, Burghoff M, Koetitz R, Abraham-

Fuchs K, Harer W. Localization of evoked neuromagnetic

600-Hz activity in the cerebral somatosensory system.

Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;91:483–487.

52. Jones MS, MacDonald KD, Choi B, Dudek FE, Barth

DS. Intracellular correlates of fast (>200 Hz) electrical

oscillations in rat somatosensory cortex. J Neurophysiol.

2000;84:1505–1518.

53. Ikeda H, Wang Y, Okada Y. Origins of the somatic

N20 and high-frequency oscillations evoked by

trigeminal stimulation in the piglets. Clin Neurophysiol.

2005;116(4):827–841.

54. Gobbele R, Waberski TD, Simon H, et al. Different

origins of low- and high-frequency components

(600 Hz) of human somatosensory evoked potentials.

Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:927–937.

55. Curio G, Mackert BM, Burghoff M, et al. Somatotopic

source arrangement of 600 Hz oscillatory magnetic

fields at the human primary somatosensory hand cortex.

Neurosci Lett. 1997;234:131–134.

56. Staba RJ, Wilson CL, Bragin A, Fried I, Engel J Jr.

Quantitative analysis of high frequency oscillations

(80–500 Hz) recorded in human epileptic hippocampus

and entorhinal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2002a;88:1743–1752.

57. Jirsch JD, Urrestarazu E, LeVan P, Olivier A, Dubeau F,

Gotman J. High-frequency oscillations during human

focal seizures. Brain. 2006;129:1593–1608.

58. Urrestarazu E, Jirsch JD, LeVan P, Hall J, Avoli M,

Dubeau F, et al. Highfrequency intracerebral EEG activity

(100-500 Hz) following interictal spikes. Epilepsia.

2006;47:1465–1476.

59. Ruggieri M, Iannetti P, Clementi M, et al. Neurofi

bromatosis type 1 and infantile spasms. Childs Nerv Syst.

2009;25(2):211–216.

60. Diebler C, Dulac O. Pediatric Neuroradiology: Cerebral

and Cranial Diseases. , New York, NY: Springer-Verlag

New York Inc. 1987.

61. Eeg-Olofsson O. The genetics of benign childhood

epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes. In: Berkovic SF,

Genton P, Hirsch E, et al., eds. Genetics of Focal Epilepsies:

Clinical Aspects and Molecular Biology. London: John

Libbey; 1999:35.

62. Huson S,Harper P, Compston D. Von Recklinghausen

neurofibromatosis: a clinical and population study in

south-east Wales. Brain. 1988;111(6):1355.

63. Fois A, Tiné A, Pavone L. Infantile spasms in patients

with neurofibromatosis type 1. Childs Nerv Syst.

1994;10(3):176–179.

64. Chugani HT, Shields WD, Shewmon DA, Olson DM,

Phelps ME, Peacock WJ. Infantile spasms: I. PET

identifies focal cortical dysgenesis in cryptogenic cases

for surgical treatment. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:406–413.

65. Chugani HT, Shewmon DA, Shields WD, et al.

Surgery for intractable infantile spasms: neuroimaging

perspectives. Epilepsia. 1993;34:764–771.

66. Wyllie E, Comair YG, Kotagal P, Raja S, Ruggieri P.

Epilepsy surgery in infants. Epilepsia. 1996a;37:

625–637.

67. Kresk P, Tichy M, Belsan T, Zamencnik J, Paulas L,

Faladova L, et al. Lifesaving epilepsy surgery for status

epilepticus caused by cortical dysplasia. Epileptic Disord.

2002;4:203–208.

68. Asano E, Juhasz C, Shah A, et al. Origin and propagation

of epileptic spasms delineated on electrocorticography.

Epilepsia 2005;46:1086–1097.

69. Haginoya K, Kon K, Takayanagi M, et al. Heterogeneity

of ictal SPECT findings in nine cases of West syndrome.

Epilepsia. 1998;39(suppl 5):26–29.

70. Lee CL, Frost JD, Jr., Swann JW, Hrachovy RA. A new

animal model of infantile spasms with unprovoked

persistent seizures. Epilepsia. 2008;49:298–307.

71. Mori K, Toda Y, Hashimoto T, Miyazaki M, Saijo T,

Ito H, Fujii E, Yamaue T, Kuroda Y. Patients with West

syndrome whose ICTAL SPECT showed focal cortical

hyperperfusion. Brain Dev. 2007;29:202–209.

72. Kramer U, Sue W, Mikati M. Focal features in West

syndrome indicating candidacy for surgery. Pediatr

Neurol. 1997;16(3):213–217.

73. Cusmai R, Ricci S, Pinard JM, Plouin P, Fariello G, Dulac

O. West syndrome due to perinatal insults. Epilepsia.

1993;34:738–742.

74. Okumura A, Hayakawa F, Kuno K, Watanabe K.

Periventricular leukomalacia and WEST syndrome. Dev

Med Child Neurol. 1996;38:13–18.

75. Ozawa H, Hashimoto T, Endo T, Kato T, Furusho J, Suzuki

Y, Takada E, Ogawa Y, Takashima S. West syndrome with

periventricular leukomalacia: a morphometric MRI study.

Pediatr Neurol. 1998;19:358–363.

76. Riikonen R. Infantile spasms: infectious disorders.

Neuropediatrics. 1993;24(5):274–280.

77. Mailles A, Vaillant V, Stahl JP. [Infectious encephalitis

in France from 2000 to 2002: the hospital database

is a valuable but limited source of information for

epidemiological studies]. Med Mal Infect. 2007;37(2):

95–102.

78. Misra UK, Tan CT, Kalita J. Viral encephalitis and

epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008;49 Suppl 6:13–18.

79. Halász P, Janszky J, Barcs G, Szucs A. Generalised

paroxysmal fast activity (GPFA) is not always a sign of

malignant epileptic encephalopathy. Seizure Eur J Epilepsy.

2004;13(4): 270–276.

80. Steriade M, and Contreras D. Spike-wave complexes

and fast components of cortically generated seizures.

I. Role of neocortex and thalamus. J Neurophysiol.

1998;80:1439–1455.

81. Cats EA, Kho KH, Van Nieuwenhuizen O, Van Veelen

CW, Gosselaar PH, and PC Van Rijen PC: Seizure

freedom after functional hemispherectomy and a

possible role for the insular cortex: the Dutch experience.

J Neurosurg. 2007;107(4 suppl):275–280.

82. Mittal S, Farmer JP, Rosenblatt B, et al. Intractable

epilepsy after a functional hemispherectomy: important

lessons from an unusual case: case report. J Neurosurg.

2001;43:510–514.

83. Viani F, Romeo A, Mastrangelo M, Viri M. Infantile

spasms combined with partial seizures: electroclinical

study of eleven cases. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1994;15:

463–471.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atlasofpediatriceeg-230702062942-5219ce2c/75/Atlas-of-Pediatric-EEG-pdf-622-2048.jpg)

![7

610 Epileptic Encephalopathy

84. Ikeda A, Ohara S, Matsumoto R, Kunieda T, Nagamine T,

Miyamoto S, et al. Role of primary sensorimotor cortices

in generating inhibitory motor response in humans.

Brain. 2000;123:1710–1721.

85. Mader E, Jr, Fisch BJ, Carey ME, Villemarette-Pittman

NR. Ictal onset slow potential shifts recorded with

hippocampal depth electrodes. Neurol Clin Neurophysiol.

2005;4:1–12.

86. Ikeda A, Taki W, Kunieda T, Terada K, Mikuni N,

Nagamine T, et al. Focal ictal direct current shifts

in human epilepsy as studied by subdural and scalp

recording. Brain. 1999a;122:827–838.

87. Rodin E, Modur P. Ictal intracranial infraslow

EEG activity. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119(10):

2188–2200.

88. Rodin E, Constantino T, vanOrman C, et al. EEG

Infraslow activity in absence and partial seizures.

Clin EEG Neurosci. 2008a;39:12–19.

89. Rodin E, Constantino T, Rampp S, Modur P. Seizure

onset determination. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;26:1–12.

90. Ikeda A, Yazawa S, Kunieda T, Araki K, Aoki T, Hattori

H, Taki W, Shibasaki H. Scalp-recorded, ictal focal

DC shift in a patient with tonic seizure. Epilepsia.

1997;38:1350—1354.

91. Vanhatalo S, Holmes M, Tallgren P, et al. Very slow

EEG responses lateralize temporal lobe seizures.

An evaluation of non-invasive DC-EEG. Neurology.

2003;60(7):1098–1104.

92. Ikeda A. DC recordings to localize the ictal onset zone.

In: Luders H, ed. Textbook of Epilepsy Surgery. London:

Informa; 2008:695–666.

93. Hrachovy RA, Frost JD Jr, Kellaway P, et al. A controlled

study of prednisone therapy in infantile spasms. Epilepsia.

1979;20:403–477.

94. Li LM, Dubeau F, Andermann F, Fish DR, Watson C,

Cascino GD, et al. Periventricular nodular heterotopia

and intractable temporal lobe epilepsy: poor outcome

after temporal lobe resection. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:

662–668.

95. d’Orsi G, Tinuper P, Bisulli F, Zaniboni A, Bernardi B,

Rubboli G, et al. Clinical features and long term outcome

of epilepsy in periventricular nodular heterotopia. Simple

compared with plus forms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.

2004;75:873–878.

96. Battaglia G, Franceschetti S, Chiapparini L, Freri

E, Bassanini S, Giavazzi A, Finardi A, Taroni F,

Granata T. Electroencephalographic recordings of

focal seizures in patients affected by periventricular

nodular heterotopia: role of the heterotopic nodules

in the genesis of epileptic discharges. J Child Neurol.

2005;20:369–377.

97. Dubeau F, Tampieri D, Lee N, Andermann E, Carpeneter

S, LeBlanc R, et al. Periventricular and subcortical

nodular heterotopia. A study of 33 patients. Brain.

1995;118:1273–1287.

98. Aghakhani Y, Kinay D, Gotman J, Soualmi L,

Andermann F, Olivier A, et al. The role of periventricular

nodular heterotopia in epileptogenesis. Brain.

2005;128:641–651.

99. Kobayashi K, Oka M, Akiyama T, et al. Very fast

rhythmic activity on scalp EEG associated with epileptic

spasms. Epilepsia. 2004;45:488–496.

100. Watanabe K. Recent advances and some problems in

the delineation of epileptic syndromes in children.

Brain Dev. 1996;18(6):423–437.

101. Watanabe K, Negoro T, Okumura A. Symptomatology of

infantile spasms. Brain Dev. 2001;23(7):453–466.

102. So N. Mesial frontal epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;39(s4):

S49–S61.

103. Arzimanoglou A, French J, Blume WT, Cross JH, Ernst

JP, Feucht M, Genton P, Guerrini R, Kluger G, Pellock

JM, Perucca E, Wheless JW. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome:

a consensus approach on diagnosis, assessment,

management, and trial methodology. Lancet Neurol.

2009;8:82–93.

104. Blume WT, David RB, Gomez MR. Generalized

sharp and slow wave complexes. Associated clinical

features and long-term follow-up. Brain. 1973;96(2):

289–306.

105. Markand ON. Slow spike-wave activity in EEG and

associated clinical features: often called 'Lennox' or

'Lennox-Gastaut' syndrome. Neurology. 1977;27(8):

746–757.

106. Markand O. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (childhood

epileptic encephalopathy). J Clin Neurophysiol.

2003;20(6):426.

107. Niedemeyer E. Epileptic seizure disorders. In:

Niedermeyer E, Da Silva F, eds. Electroencephalography:

Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields.

Amsterdams: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

108. C.A. Tassinari and G. Ambrosetto, Tonic seizures in the

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: semiology and differential

diagnosis. In: Degan R, ed. The Lennox-Gastaut

Syndrome. New York: Alan R. Liss; 1988:109–124.

109. Beaumanoir A. The Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: a

personal study. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol

Suppl. 1982;35:85–99.

110. Gabor A, Seyal M. Effect of sleep on the electrographic

manifestations of epilepsy. J Clin Neurophysiol.

1986;3(1):23.

111. Brenner RP, Atkinson R. Generalized paroxysmal fast

activity: electroencephalographic and clinical features.

Ann Neurol. 1982;11(4):386–390.

112. Brenner R, Atkinson R. Generalized paroxysmal fast

activity: electroencephalographic and clinical features.

Ann Neurol. 2004;11(4):386–390.

113. Halász P, Janszky J, Barcs G, Szucs A. Generalised

paroxysmal fast activity (GPFA) is not always a sign

of malignant epileptic encephalopathy. Seizure Eur J

Epilepsy. 2004;13(4):270–276.

114. Markand ON. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (childhood

epileptic encephalopathy). J Clin Neurophysiol.

2003;20(6):426–441.

115. Brenner RP, Atkinson R. Generalized paroxysmal fast

activity: electroencephalographic and clinical features.

Ann Neurol. 1982;11:386–390.

116. Hrachovy RA, Frost JD, Jr. The EEG in selected

generalized seizures. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;23(4):312.

117. Horita H, Kumagai K, Maekawa K. Overnight

polygraphic study of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Brain

Dev. 1987;9(6):627.

118. Gastaut H, Tassinari CA. (1975) Epilepsies. In: Remond

A, ed. Handbook of electroencephalography and clinical

neurophysiology, vol. 13A. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 39–45.

119. Angelini L, Broggi G, Riva D and Solero CL, A case

of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome successfully treated by

removal of a parieto-temporal astrocytoma. Epilepsia.

1979;20:665–669.

120. Ishikawa T, Yamada K, Kanayama M. A case of Lennox-

Gastaut syndrome improved remarkably by surgical

treatment of a porencephalic cyst: a consideration on the

generalized corticoreticular epilepsy [Japanese]. No To

Hattatsu. 1983;9:356–365.

121. Quarato PP, Gennaro GD, Manfredi M, Esposito V:

Atypical Lennox-Gastaut syndrome successfully treated

with removal of a parietal dysembryoplastic tumour.

Seizure. 2002;11:325–329.

122. Beaumanoir A, Blume WT. The Lennox-Gastaut

syndrome. In: Beaumanoir A, Dravet C, eds. Epileptic

Syndromes in Infancy, Childhood and Adolescence.

Montrouge, France: John Libbey Eurotext. 2005:125–148.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atlasofpediatriceeg-230702062942-5219ce2c/75/Atlas-of-Pediatric-EEG-pdf-623-2048.jpg)

![8

674 Generalized Epilepsy

41. Doose H. EEG in Childhood Epilepsy. 1st ed. Montrouge,

France; John Libbey; 2003 Eurotext.

42. Gastaut H, Regis H. On the subject of Lennox's"

akinetic" petit mal. in memory of WG Lennox. Epilepsia.

1961;2:298.

43. Guerrini R, Parmeggiani L, Bonanni P, Kaminska

A, Dulac O. Myoclonic astatic epilepsy. In: Roger J,

Bureau M, Dravet C, Genton P, Tassinari CA, Wolf

P, eds. Epilepsy Syndromes in Infancy, Childhood and

Adolescence. Montrouge: John Libbey Eurotext Ltd;

2005:115–124.

44. Ohtahara S, Yamatogi Y. Epilepsy with myoclonic-astatic

seizures. Epilepsies. 2000:223.

45. Dravet C, Bureau M, Oguni H, Fukuyama Y, Cokar O.

(2005) Severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (Dravet

syndrome). In: Roger J, Bureau M, Dravet C, Genton P,

Tassinari CA, Wolf P, eds. Epileptic Syndromes In Infancy,

Childhood and AdolescenceMountrouge: John Libbey

Eurotext Ltd; 2005:89–113.

46. Guerrini R, Aicardi J. Epileptic encephalopathies with

myoclonic seizures in infants and children (severe

myoclonic epilepsy and myoclonic-astatic epilepsy).

J Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;20(6):449.

47. Laan LA, Vein AA. Angelman syndrome: is there a

characteristic EEG? Brain Dev. 2005;27(2):80–87.

48. Williams CA., Beaudet AL, Clayton-Smith J, Knoll JH,

Kyllerman M, Laan LA, Magenis RE, Moncla A, Schinzel

AA, Summers JA, et al. Angelman syndrome 2005:

updated consensus for diagnostic criteria. Am J Med

Genet A. 2006;140:413–418.

49. Korff C, Kelley K, Nordli Jr D. Notched delta, phenotype,

and Angelman syndrome. J Clin Neurophysiol.

2005;22(4):238.

50. Guerrini R, Carrozzo R, Rinaldi R, Bonanni P. Angelman

syndrome: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, and

management of symptoms. Pediatr Drugs. 2003;5:647–661.

51. Glaze DG. Neurophysiology of Rett syndrome. J Child

Neurol. 2005;20(9):740–746.

52. Niedermeyer E, Rett A, Renner H, Murphy M, Naidu S

Rett syndrome and the electroencephalogram. Am J Med

Genet Suppl. 1986;1:195–199.

53. Palmini A, Andermann F, Olivier A, Tampieri D,

Robitaille Y. Focal neuronal migration disorders and

intractable partial epilepsy: results of surgical treatment.

Ann Neurol. 1991;30:750–757.

54. Granata T, Battaglia G, D'Incerti L, et al. Double cortex

syndrome: electroclinical study of three cases. Ital J

Neurol Sci. 1994;15(1):15–23.

55. Grant AC, Rho JM. Ictal EEG patterns in band

heterotopia. Epilepsia. 2002;43(4):403–407.

56. Kato M, Dobyns W. Lissencephaly and the molecular

basis of neuronal migration. Hum Mol Genet.

2003;12(Rev 1):R89.

57. Gastaut H, Pinsard M, Raybaud O, et al. Lissencephaly

(agyria-pachygyria): clinical fi ndings and serial

EEG studies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1987;29(2):

167–180.

58. Worle H, Keimer R, Kohler B. [Miller-Dieker syndrome

(type I lissencephaly) with specific EEG changes].

Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 1990;138(9):615–618.

59. De Rijk-van Andel J, Arts W, De Weerd A. EEG

and evoked potentials in a series of 21 patients with

lissencephaly type I. Neuropediatrics. 1992;23(1):4–9.

60. Canafoglia L, Franceschetti S, Antozzi C, Carrara

F, Farina L, Granata T, et al. Epileptic phenotypes

associated with mitochondrial disorders. Neurology.

2001;56:1340–1346.

61. Acharya J, Satishchandra P, Shankar S. Familial

progressive myoclonus epilepsy: clinical and

electrophysiologic observations. Epilepsia.

1995;36(5):429–434.

62. Noachtar S, Arnold S eds. Clonic seizures. In: Lüders

H, Noachtar S, eds. Epileptic Seizures: Pathophysiology

and Clinical Semiology. Churchill Livingstone

Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000.

63. Nabbout R, Soufflet C, Plouin P, Dulac O. Pyridoxine

dependent-epilepsy: a suggestive electroclinical pattern.

Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1999;81:F125–F129.

64. Mikati M, Trevathan E, Krishnamoorthy K, et al.

Pyridoxine dependent epilepsy: EEG investigations

and long-term follow-up. EEG Clin Neurophysiol.

1991;78:215–221.

65. Pampiglione G, Harden A. So-called neuronal ceroid

lipofuscinosis. Neurophysiological studies in 60 children.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1977;40(4):323–330.

66. Blume W, Kaibara M. Atlas of Pediatric Encephalography.

Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1999.

67. Remler, Bradley W. Falls and drop attacks. In: Bradley

W, ed. Neurology in Clinical Practice. Churchill

Livingstone Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis; 1996.

68. Raieli V, Puma D, Brighina F. Role of neurophysiology

in the clinical practice of primary pediatric headaches.

Drug Dev Res. 2007;68(7).

69. Pavese N, Canapicchi R, Nuti A, et al. White matter

MRI hyperintensities in a hundred and twenty-nine

consecutive migraine patients. Cephalalgia. 1994;14:

312–345.

70. DiMario Jr F. Breath-holding spells in childhood. Arch

Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1992;146(1):125.

71. Low N, Gibbs E, Gibbs F. Electroencephalographic

findings in breath holding spells. Pediatrics.

1955;15(5):595.

72. Gastaut H, Fischer-Williams M. Electro-

encephalographic study of syncope; its differentiation

from epilepsy. Lancet. 1957;273(7004):1018.

73. Brenner R. Electroencephalography in syncope. J Clin

Neurophysiol. 1997;14(3):197.

74. Emery ES. Status epilepticus secondary to breath-holding

and pallid syncopal spells. Neurology. 1990;40:859.

75. Moorjani B, Rothner A, Kotagal P. Breath-holding spells

and prolonged seizures. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:512–513.

76. Stephenson JBP. Fits and Faints. London: Mac Keith

Press; 1990.

77. Breningstall G. Breath-holding spells. Pediatr Neurol.

1996;14(2):91–97.

78. Fogoros R. Cardiac arrhythmias. Syncope and stroke.

Neurologic Clinics. 1993;11(2):375.

79. Kapoor W, Hanusa B. Is syncope a risk factor for poor

outcomes? Comparison of patients with and without

syncope. Am J Med. 1996;100(6):646–655.

80. Morrell M. Differential diagnosis of seizures. Neurologic

Clinics. 1993;11(4):737.

81. Abboud F. Neurocardiogenic syncope. N Engl J Med.

1993;328(15):1117.

82. Schott G, McLeod A, Jewitt D. Cardiac arrhythmias

that masquerade as epilepsy. BMJ. 1977;1(6074):1454.

83. Ballardie F, Murphy R, Davis J. Epilepsy: a presentation

of the Romano-Ward syndrome. BMJ. 1983;287(6396):896.

84. Blumhardt L. Ambulatory ECG and EEG monitoring of

patients with blackouts. Br J Hosp Med. 1986;36(5):354.

85. Jennett B, Gleave J, Wilson P. Brain death in three

neurosurgical units. BMJ. 1981;282(6263):533.

86. Maulsby R, Kellaway P. Transient hypoxic crises in

children. In: Neurological and Electroencephalographic

Correlative Studies in Infancy. 1964:349–360.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atlasofpediatriceeg-230702062942-5219ce2c/75/Atlas-of-Pediatric-EEG-pdf-687-2048.jpg)

![675

Focal Epilepsy

Interictal epileptiform discharges

(IEDs) associated with epilepsy

With clinical correlation, the high sensitivity and the

䡲

specificity of IEDs for seizure disorders support the

use of IEDs as the electrophysiological signature

of an epileptogenic brain.

IEDs represent the macroscopic field created by

䡲

the summation of potentials from pathologically

synchronized bursting neurons.

Common types of IEDs

Spikes, polyspikes,

䡲 sharp waves, and spike-and-

slow-wave complexes, which can be either focal or

generalized.

The main types of generalized IED patterns are:

䡲

3-Hz spike and slow wave

䊳

Sharp and slow wave

䊳

Atypical repetitive spike and slow wave

䊳

Multiple spike and slow wave

䊳

Paroxysmal fast activity (PFA)

䊳

Definition of IEDs and features

The epileptiform sharp waves and spikes are:

䡲

Transient waveforms that may repeat, and arise

䊳

abruptly out of the EEG background activity.

The waveforms are asymmetric with more than

䊳

one phase (usually two or three). In contrast,

nonepileptiform, sharply contoured transients such

as wicket waves are often approximately symmetric.

The epileptiform spikes and sharp waves are often

䡲

followed by a smoothly contoured slow wave

(spike-and-slow-wave complexes), which disrupts

the ongoing EEG background rhythm.

The sharp wave or spike is produced by an abrupt

䡲

change in voltage polarity that occurs over several

milliseconds. The duration of an epileptiform sharp

wave is between 70 and 200 msec, and the duration

of spikes is less than 70 msec, although the distinction

is of unclear clinical importance.

The epileptiform discharge should have a physiologic

䡲

field and not be confined to a single electrode except

in newborn.

Besides interictal epileptiform spikes and sharp waves,

䡲

intermittent rhythmic delta activity over the temporal

region (TIRDA) has similar specificity for temporal lobe

epilepsy.

There are also

䡲 localized, periodic patterns of IEDs that

are associated with seizures. These periodic patterns

of IEDs can be lateralized to one hemisphere, as seen

in periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges (PLEDs),

or can be bilateral or multifocal (BiPLEDs).

Types of interictal EEG patterns

Spikes, spike-wave discharges, polyspikes, or sharp

䡲

waves (interictal epileptiform discharges [IEDs]).

Broad

䡲 sharp or polyphasic sharp waves (duration >

200 msec).

Periodic lateralized epileptiform activity (PLEDs) or

䡲

bilateral independent periodic lateralized epileptiform

activity (BiPLEDs) in an acute/subacute cerebral insult.

Paroxysmal fast activity (PFA)

䡲 —most commonly in

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

Hypsarrhythmia in infantile spasm (hemihypsarrhythmia

䡲

in focal, symptomatic infantile spasm).

Temporal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (TIRDA)

䡲

in mesial temporal epilepsy.

Occipital intermittent rhythmic delta activity (OIRDA)

䡲

in generalized epilepsy, especially absence epilepsy.

Frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity

䡲

(FIRDA) rarely represents IED.

Continuous, near-continuous, or long trains of

䡲

localized spikes or rhythmic sharp waves (intrinsic

epileptogenicity) in structural abnormalities,

especially focal cortical dysplasia (FCD).

Regional polyspikes (especially in extratemporal

䡲

region) are highly associated with FCD (80%).

Focal low-voltage fast activity or electrodecrement

䡲

in scalp EEG corresponding to high-frequency

oscillation (HFO) in intracranial EEG.

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atlasofpediatriceeg-230702062942-5219ce2c/75/Atlas-of-Pediatric-EEG-pdf-688-2048.jpg)