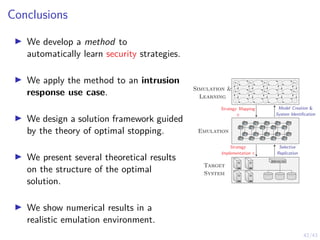

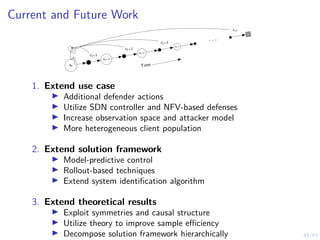

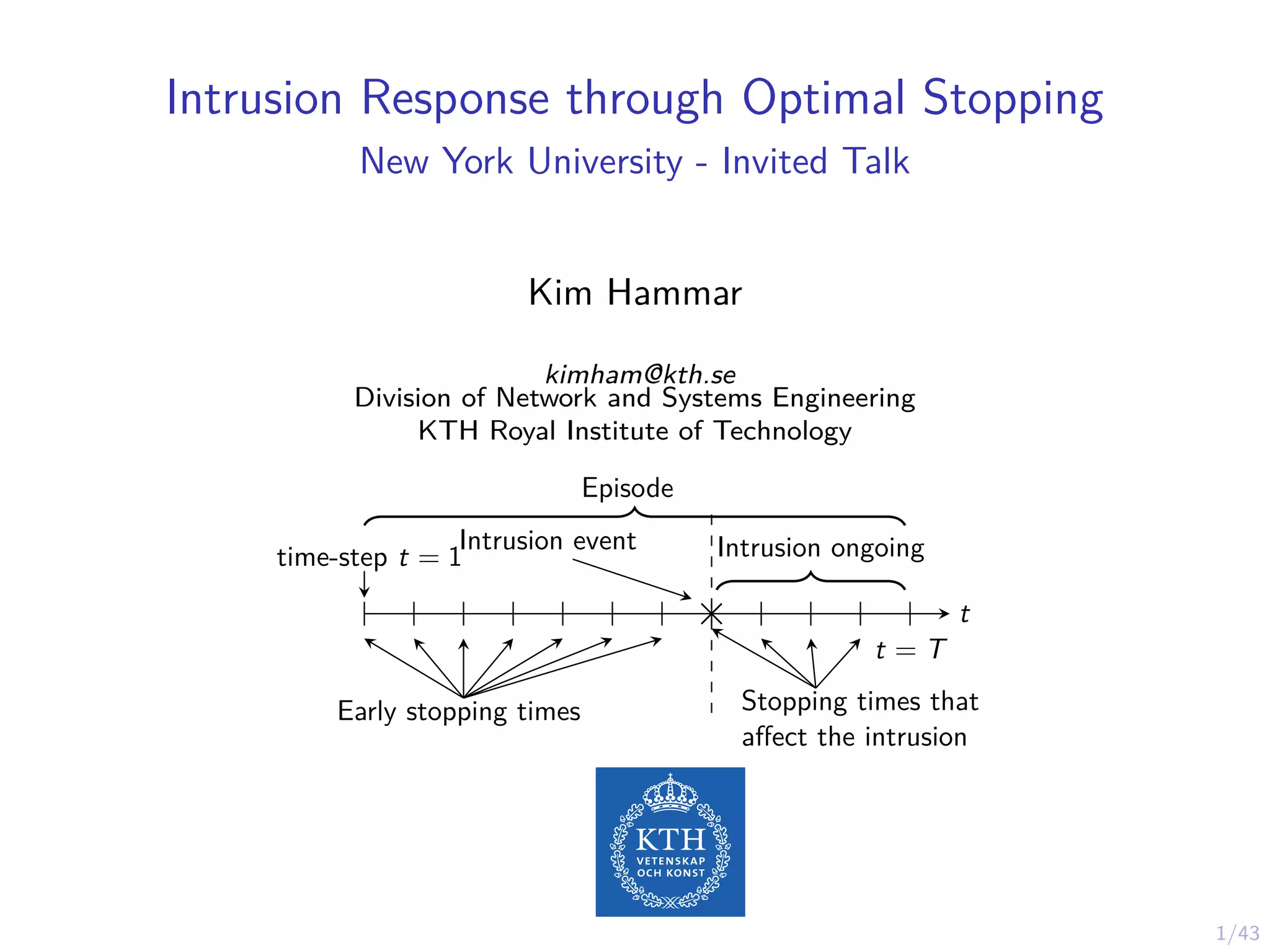

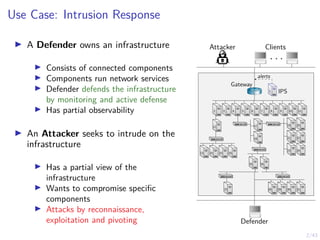

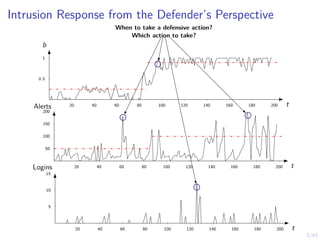

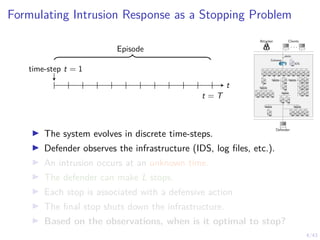

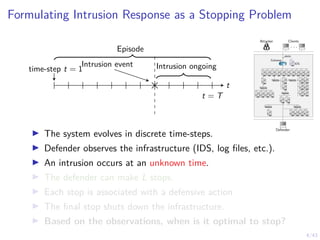

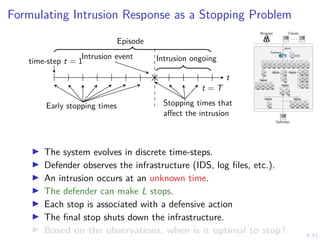

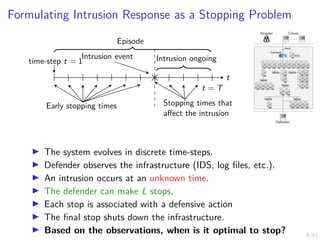

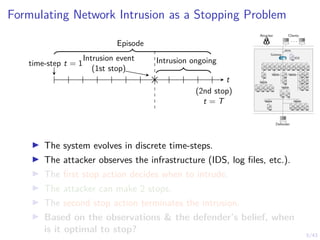

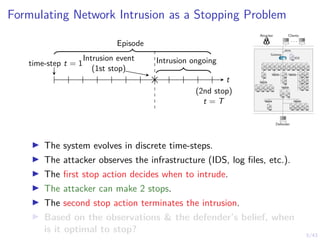

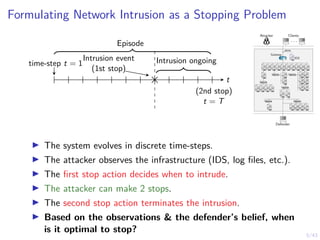

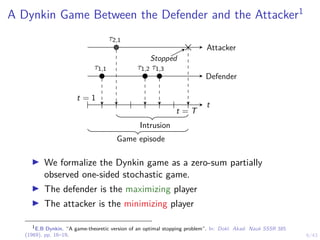

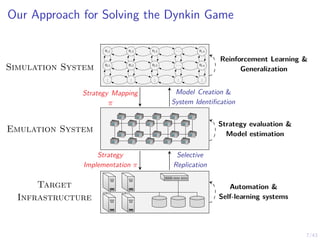

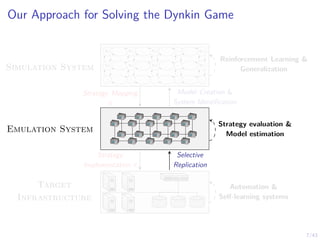

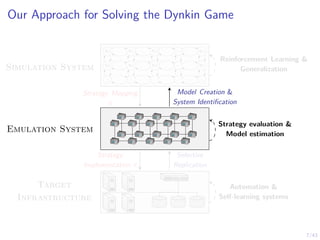

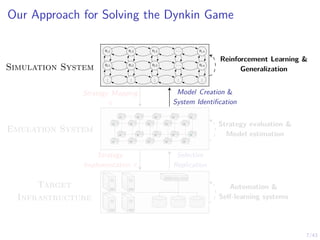

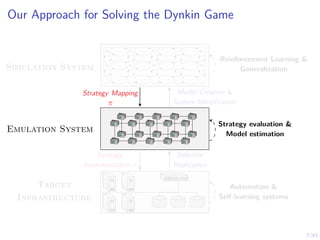

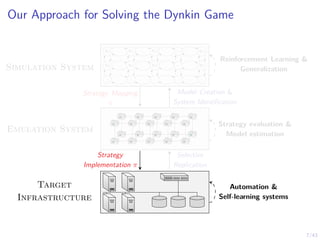

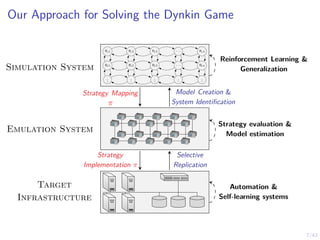

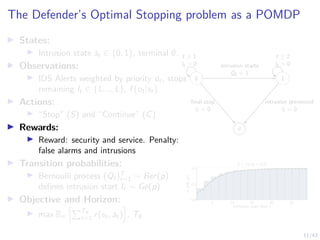

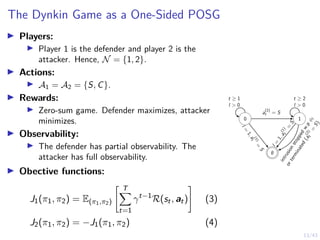

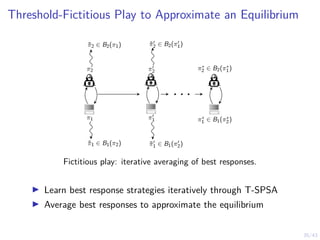

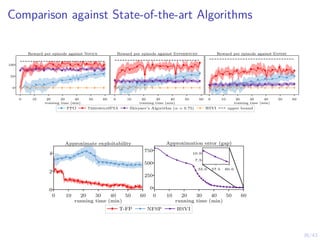

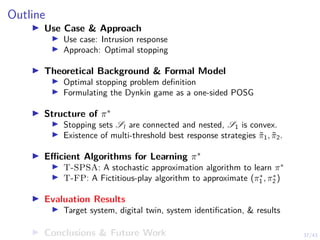

This document discusses formulating intrusion response as an optimal stopping problem known as a Dynkin game. The system evolves in discrete time steps with an attacker and defender. The defender observes the infrastructure and aims to determine the optimal time to stop and take defensive action based on observations. The approach involves modeling the interaction as a zero-sum partially observed stochastic game and using reinforcement learning to determine optimal strategies for both players.

![12/43

The Attacker’s Optimal Stopping problem as an MDP

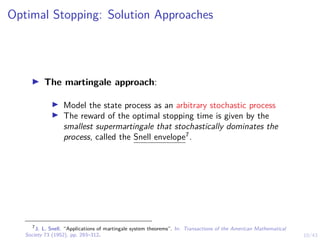

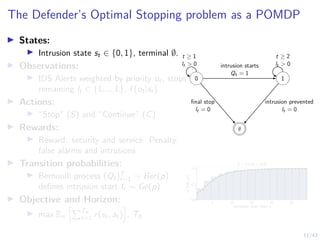

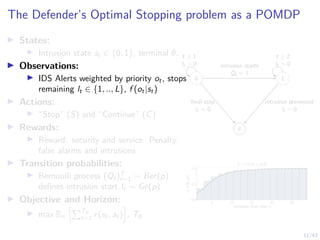

I States:

I Intrusion state st ∈ {0, 1}, terminal ∅,

defender belief b ∈ [0, 1].

I Actions:

I “Stop” (S) and “Continue” (C)

I Rewards:

I Reward: denial of service and intrusion.

Penalty: detection

I Transition probabilities:

I Intrusion starts and ends when the

attacker takes stop actions

I Objective and Horizon:

I max Eπ

hPT∅

t=1 r(st, at)

i

, T∅

0 1

∅

t ≥ 1 t ≥ 2

intrusion starts

at = 1

final stop detected](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-47-320.jpg)

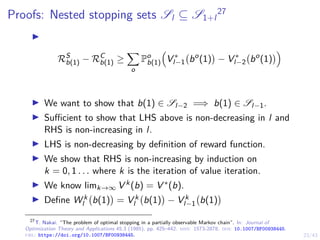

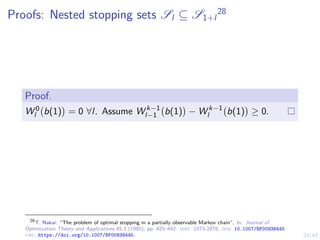

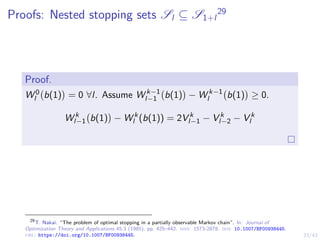

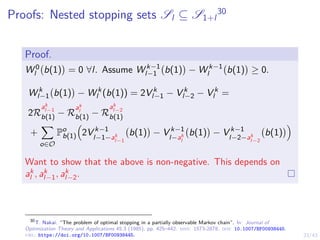

![15/43

Structural Result: Optimal Multi-Threshold Policy

Theorem

Given the intrusion response POMDP, the following holds:

1. Sl−1 ⊆ Sl for l = 2, . . . L.

2. If L = 1, there exists an optimal threshold α∗ ∈ [0, 1] and an

optimal defender policy of the form:

π∗

L(b(1)) = S ⇐⇒ b(1) ≥ α∗

(5)

3. If L ≥ 1 and fX is totally positive of order 2 (TP2), there

exists L optimal thresholds α∗

l ∈ [0, 1] and an optimal

defender policy of the form:

π∗

l (b(1)) = S ⇐⇒ b(1) ≥ α∗

l , l = 1, . . . , L (6)

where α∗

l is decreasing in l.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-50-320.jpg)

![15/43

Structural Result: Optimal Multi-Threshold Policy

Theorem

Given the intrusion response POMDP, the following holds:

1. Sl−1 ⊆ Sl for l = 2, . . . L.

2. If L = 1, there exists an optimal threshold α∗ ∈ [0, 1] and an

optimal defender policy of the form:

π∗

L(b(1)) = S ⇐⇒ b(1) ≥ α∗

(7)

3. If L ≥ 1 and fX is totally positive of order 2 (TP2), there

exists L optimal thresholds α∗

l ∈ [0, 1] and an optimal

defender policy of the form:

π∗

l (b(1)) = S ⇐⇒ b(1) ≥ α∗

l , l = 1, . . . , L (8)

where α∗

l is decreasing in l.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-51-320.jpg)

![15/43

Structural Result: Optimal Multi-Threshold Policy

Theorem

Given the intrusion response POMDP, the following holds:

1. Sl−1 ⊆ Sl for l = 2, . . . L.

2. If L = 1, there exists an optimal threshold α∗ ∈ [0, 1] and an

optimal defender policy of the form:

π∗

L(b(1)) = S ⇐⇒ b(1) ≥ α∗

(9)

3. If L ≥ 1 and fX is totally positive of order 2 (TP2), there

exists L optimal thresholds α∗

l ∈ [0, 1] and an optimal

defender policy of the form:

π∗

l (b(1)) = S ⇐⇒ b(1) ≥ α∗

l , l = 1, . . . , L (10)

where α∗

l is decreasing in l.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-52-320.jpg)

![15/43

Structural Result: Optimal Multi-Threshold Policy

Theorem

Given the intrusion response POMDP, the following holds:

1. Sl−1 ⊆ Sl for l = 2, . . . L.

2. If L = 1, there exists an optimal threshold α∗ ∈ [0, 1] and an

optimal defender policy of the form:

π∗

L(b(1)) = S ⇐⇒ b(1) ≥ α∗

(11)

3. If L ≥ 1 and fX is totally positive of order 2 (TP2), there

exists L optimal thresholds α∗

l ∈ [0, 1] and an optimal

defender policy of the form:

π∗

l (b(1)) = S ⇐⇒ b(1) ≥ α∗

l , l = 1, . . . , L (12)

where α∗

l is decreasing in l.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-53-320.jpg)

![16/43

Structural Result: Optimal Multi-Threshold Policy

b(1)

0 1

belief space B = [0, 1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-54-320.jpg)

![16/43

Structural Result: Optimal Multi-Threshold Policy

b(1)

0 1

belief space B = [0, 1]

S1

α∗

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-55-320.jpg)

![16/43

Structural Result: Optimal Multi-Threshold Policy

b(1)

0 1

belief space B = [0, 1]

S1

S2

α∗

1

α∗

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-56-320.jpg)

![16/43

Structural Result: Optimal Multi-Threshold Policy

b(1)

0 1

belief space B = [0, 1]

S1

S2

.

.

.

SL

α∗

1

α∗

2

α∗

L

. . .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-57-320.jpg)

![19/43

Proofs: S1 is convex10

I S1 is convex if:

I for any two belief states b1, b2 ∈ S1

I any convex combination of b1, b2 is also in S1

I i.e. b1, b2 ∈ S1 =⇒ λb1 + (1 − λ)b2 ∈ S1 for λ ∈ [0, 1].

I Since V ∗(b) is convex:

V ∗

(λb1 + (1 − λ)b2) ≤ λV ∗

(b1) + (1 − λ)V (b2)

I Since b1, b2 ∈ S1:

V ∗

(b1) = Q∗

(b1, S) S=stop

V ∗

(b2) = Q∗

(b2, S) S=stop

10

Vikram Krishnamurthy. Partially Observed Markov Decision Processes: From Filtering to Controlled Sensing.

Cambridge University Press, 2016. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316471104.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-63-320.jpg)

![19/43

Proofs: S1 is convex11

I S1 is convex if:

I for any two belief states b1, b2 ∈ S1

I any convex combination of b1, b2 is also in S1

I i.e. b1, b2 ∈ S1 =⇒ λb1 + (1 − λ)b2 ∈ S1 for λ ∈ [0, 1].

I Since V ∗(b) is convex:

V ∗

(λb1 + (1 − λ)b2) ≤ λV ∗

(b1) + (1 − λ)V (b2)

I Since b1, b2 ∈ S1:

V ∗

(b1) = Q∗

(b1, S) S=stop

V ∗

(b2) = Q∗

(b2, S) S=stop

11

Vikram Krishnamurthy. Partially Observed Markov Decision Processes: From Filtering to Controlled Sensing.

Cambridge University Press, 2016. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316471104.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-64-320.jpg)

![19/43

Proofs: S1 is convex12

I S1 is convex if:

I for any two belief states b1, b2 ∈ S1

I any convex combination of b1, b2 is also in S1

I i.e. b1, b2 ∈ S1 =⇒ λb1 + (1 − λ)b2 ∈ S1 for λ ∈ [0, 1].

I Since V ∗(b) is convex:

V ∗

(λb1 + (1 − λ)b2) ≤ λV ∗

(b1) + (1 − λ)V (b2)

I Since b1, b2 ∈ S1:

V ∗

(b1) = Q∗

(b1, S) S=stop

V ∗

(b2) = Q∗

(b2, S) S=stop

12

Vikram Krishnamurthy. Partially Observed Markov Decision Processes: From Filtering to Controlled Sensing.

Cambridge University Press, 2016. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316471104.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-65-320.jpg)

![20/43

Proofs: S1 is convex13

Proof.

Assume b1, b2 ∈ S1. Then for any λ ∈ [0, 1]:

V ∗

λb1(1) + (1 − λ)b2(1)

≤ λV ∗

b1(1)) + (1 − λ)V ∗

(b2(1)

= λQ∗

(b1, S) + (1 − λ)Q∗

(b2, S)

13

Vikram Krishnamurthy. Partially Observed Markov Decision Processes: From Filtering to Controlled Sensing.

Cambridge University Press, 2016. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316471104.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-66-320.jpg)

![20/43

Proofs: S1 is convex14

Proof.

Assume b1, b2 ∈ S1. Then for any λ ∈ [0, 1]:

V ∗

λb1(1) + (1 − λ)b2(1)

≤ λV ∗

b1(1)) + (1 − λ)V ∗

(b2(1)

= λQ∗

(b1, S) + (1 − λ)Q∗

(b2, S)

= λR∅

b1

+ (1 − λ)R∅

b2

=

X

s

(λb1(s) + (1 − λ)b2(s))R∅

s

14

Vikram Krishnamurthy. Partially Observed Markov Decision Processes: From Filtering to Controlled Sensing.

Cambridge University Press, 2016. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316471104.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-67-320.jpg)

![20/43

Proofs: S1 is convex15

Proof.

Assume b1, b2 ∈ S1. Then for any λ ∈ [0, 1]:

V ∗

λb1(1) + (1 − λ)b2(1)

≤ λV ∗

b1(1)) + (1 − λ)V ∗

(b2(1)

= λQ∗

(b1, S) + (1 − λ)Q∗

(b2, S)

= λR∅

b1

+ (1 − λ)R∅

b2

=

X

s

(λb1(s) + (1 − λ)b2(s))R∅

s

= Q∗

λb1 + (1 − λ)b2, S

15

Vikram Krishnamurthy. Partially Observed Markov Decision Processes: From Filtering to Controlled Sensing.

Cambridge University Press, 2016. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316471104.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-68-320.jpg)

![20/43

Proofs: S1 is convex16

Proof.

Assume b1, b2 ∈ S1. Then for any λ ∈ [0, 1]:

V ∗

λb1(1) + (1 − λ)b2(1)

≤ λV ∗

b1(1)) + (1 − λ)V ∗

(b2(1)

= λQ∗

(b1, S) + (1 − λ)Q∗

(b2, S)

= λR∅

b1

+ (1 − λ)R∅

b2

=

X

s

(λb1(s) + (1 − λ)b2(s))R∅

s

= Q∗

λb1 + (1 − λ)b2, S

≤ V ∗

λb1(1) + (1 − λ)b2(1)

the last inequality is because V ∗ is optimal. The second-to-last is

because there is just a single stop.

16

Vikram Krishnamurthy. Partially Observed Markov Decision Processes: From Filtering to Controlled Sensing.

Cambridge University Press, 2016. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316471104.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-69-320.jpg)

![20/43

Proofs: S1 is convex17

Proof.

Assume b1, b2 ∈ S1. Then for any λ ∈ [0, 1]:

V ∗

λb1(1) + (1 − λ)b2(1)

≤ λV ∗

b1(1)) + (1 − λ)V ∗

(b2(1)

= λQ∗

(b1, S) + (1 − λ)Q∗

(b2, S)

= Q∗

λb1 + (1 − λ)b2, S

≤ V ∗

λb1(1) + (1 − λ)b2(1)

the last inequality is because V ∗ is optimal. The second-to-last is

because there is just a single stop. Hence:

Q∗

λb1 + (1 − λ)b2, S

= V ∗

λb1(1) + (1 − λ)b2(1)

b1, b2 ∈ S1 =⇒ (λb1 + (1 − λ)) ∈ S1. Therefore S1 is

convex.

17

Vikram Krishnamurthy. Partially Observed Markov Decision Processes: From Filtering to Controlled Sensing.

Cambridge University Press, 2016. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316471104.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-70-320.jpg)

![20/43

Proofs: S1 is convex18

b(1)

0 1

belief space B = [0, 1]

S1

α∗

1 β∗

1

18

Vikram Krishnamurthy. Partially Observed Markov Decision Processes: From Filtering to Controlled Sensing.

Cambridge University Press, 2016. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316471104.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-71-320.jpg)

![21/43

Proofs: Single-threshold policy is optimal if L = 119

I In our case, B = [0, 1]. We know S1 is a convex subset of B.

I Consequence, S1 = [α∗, β∗]. We show that β∗ = 1.

I If b(1) = 1, using our definition of the reward function, the

Bellman equation states:

π∗

(1) ∈ arg max

{S,C}

150 + V ∗

(∅)

| {z }

a=S

, −90 +

X

o∈O

Z(o, 1, C)V ∗

bo

C (1)

| {z }

a=C

#

= arg max

{S,C}

150

|{z}

a=S

, −90 + V ∗

(1)

| {z }

a=C

#

= S i.e π∗

(1) =Stop

I Hence 1 ∈ S1. It follows that S1 = [α∗, 1] and:

π∗

b(1)

=

(

S if b(1) ≥ α∗

C otherwise

19

Kim Hammar and Rolf Stadler. “Learning Intrusion Prevention Policies through Optimal Stopping”. In:

International Conference on Network and Service Management (CNSM 2021).

http://dl.ifip.org/db/conf/cnsm/cnsm2021/1570732932.pdf. Izmir, Turkey, 2021.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-72-320.jpg)

![21/43

Proofs: Single-threshold policy is optimal if L = 120

I In our case, B = [0, 1]. We know S1 is a convex subset of B.

I Consequence, S1 = [α∗, β∗]. We show that β∗ = 1.

I If b(1) = 1, using our definition of the reward function, the

Bellman equation states:

π∗

(1) ∈ arg max

{S,C}

150 + V ∗

(∅)

| {z }

a=S

, −90 +

X

o∈O

Z(o, 1, C)V ∗

bo

C (1)

| {z }

a=C

#

= arg max

{S,C}

150

|{z}

a=S

, −90 + V ∗

(1)

| {z }

a=C

#

= S i.e π∗

(1) =Stop

I Hence 1 ∈ S1. It follows that S1 = [α∗, 1] and:

π∗

b(1)

=

(

S if b(1) ≥ α∗

C otherwise

20

Kim Hammar and Rolf Stadler. “Learning Intrusion Prevention Policies through Optimal Stopping”. In:

International Conference on Network and Service Management (CNSM 2021).

http://dl.ifip.org/db/conf/cnsm/cnsm2021/1570732932.pdf. Izmir, Turkey, 2021.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-73-320.jpg)

![21/43

Proofs: Single-threshold policy is optimal if L = 121

I In our case, B = [0, 1]. We know S1 is a convex subset of B.

I Consequence, S1 = [α∗, β∗]. We show that β∗ = 1.

I If b(1) = 1, using our definition of the reward function, the

Bellman equation states:

π∗

(1) ∈ arg max

{S,C}

150 + V ∗

(∅)

| {z }

a=S

, −90 +

X

o∈O

Z(o, 1, C)V ∗

bo

C (1)

| {z }

a=C

#

= arg max

{S,C}

150

|{z}

a=S

, −90 + V ∗

(1)

| {z }

a=C

#

= S i.e π∗

(1) =Stop

I Hence 1 ∈ S1. It follows that S1 = [α∗, 1] and:

π∗

b(1)

=

(

S if b(1) ≥ α∗

C otherwise

21

Kim Hammar and Rolf Stadler. “Learning Intrusion Prevention Policies through Optimal Stopping”. In:

International Conference on Network and Service Management (CNSM 2021).

http://dl.ifip.org/db/conf/cnsm/cnsm2021/1570732932.pdf. Izmir, Turkey, 2021.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-74-320.jpg)

![22/43

Proofs: Single-threshold policy is optimal if L = 1

b(1)

0 1

belief space B = [0, 1]

S1

α∗

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-75-320.jpg)

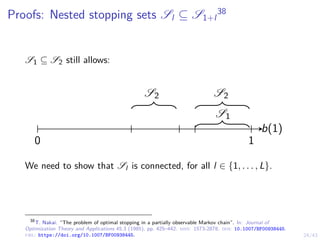

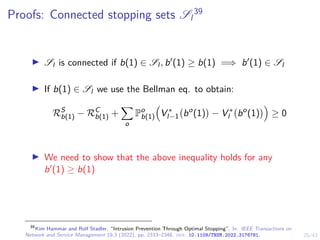

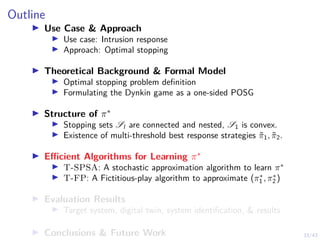

![31/43

Proofs: Optimal multi-threshold policy π∗

l

49

We have shown that:

I S1 = [α∗

1, 1]

I Sl ⊆ Sl+1

I Sl is connected (convex) for l = 1, . . . , L

It follows that, Sl = [α∗

l , 1] and α∗

1 ≥ α∗

2 ≥ . . . ≥ α∗

L.

b(1)

0 1

belief space B = [0, 1]

S1

S2

.

.

.

SL

α∗

1

α∗

2

α∗

L

. . .

49

Kim Hammar and Rolf Stadler. “Intrusion Prevention Through Optimal Stopping”. In: IEEE Transactions on

Network and Service Management 19.3 (2022), pp. 2333–2348. doi: 10.1109/TNSM.2022.3176781.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-103-320.jpg)

![32/43

Structural Result: Best Response Multi-Threshold Attacker

Strategy

Theorem

Given the intrusion MDP, the following holds:

1. Given a defender strategy π1 ∈ Π1 where π1(S|b(1)) is

non-decreasing in b(1) and π1(S|1) = 1, then there exist

values β̃0,1, β̃1,1, . . ., β̃0,L, β̃1,L ∈ [0, 1] and a best response

strategy π̃2 ∈ B2(π1) for the attacker that satisfies

π̃2,l (0, b(1)) = C ⇐⇒ π1,l (S|b(1)) ≥ β̃0,l (16)

π̃2,l (1, b(1)) = S ⇐⇒ π1,l (S|b(1)) ≥ β̃1,l (17)

for l ∈ {1, . . . , L}.

Proof.

Follows the same idea as the proof for the defender case.

See50.

50

Kim Hammar and Rolf Stadler. Learning Near-Optimal Intrusion Responses Against Dynamic Attackers. 2023.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-104-320.jpg)

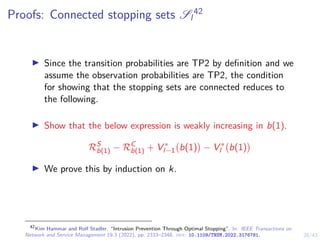

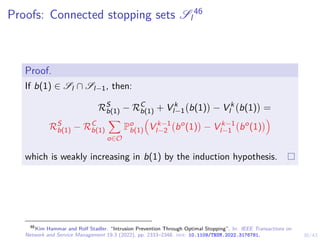

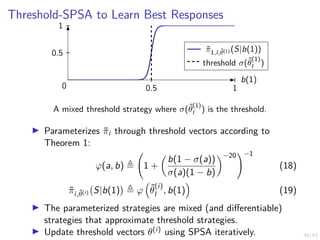

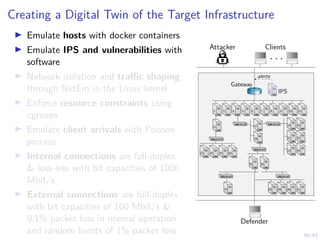

![41/43

Learning Curves in Simulation and Digital Twin

0

50

100

Novice

Reward per episode

0

50

100

Episode length (steps)

0.0

0.5

1.0

P[intrusion interrupted]

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

P[early stopping]

5

10

Duration of intrusion

−50

0

50

100

experienced

0

50

100

150

0.0

0.5

1.0

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

0

5

10

0 20 40 60

training time (min)

−50

0

50

100

expert

0 20 40 60

training time (min)

0

50

100

150

0 20 40 60

training time (min)

0.0

0.5

1.0

0 20 40 60

training time (min)

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

0 20 40 60

training time (min)

0

5

10

15

20

πθ,l simulation πθ,l emulation (∆x + ∆y) ≥ 1 baseline Snort IPS upper bound](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nyuinvitedtalkoptimalstoppinghammar30jan-230130171136-e7c97858/85/Intrusion-Response-through-Optimal-Stopping-120-320.jpg)