Japanese debt crisis

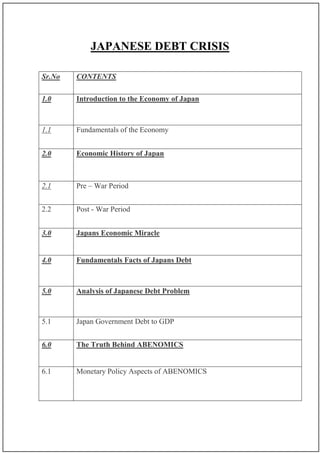

- 1. JAPANESE DEBT CRISIS Sr.No CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction to the Economy of Japan 1.1 Fundamentals of the Economy 2.0 Economic History of Japan 2.1 Pre – War Period 2.2 Post - War Period 3.0 Japans Economic Miracle 4.0 Fundamentals Facts of Japans Debt 5.0 Analysis of Japanese Debt Problem 5.1 Japan Government Debt to GDP 6.0 The Truth Behind ABENOMICS 6.1 Monetary Policy Aspects of ABENOMICS

- 2. 6.2 ABENOMICS Approach to Fiscal Policy Reforms 6.3 Structural Reforms 6.4 ABENOMICS in a Nutshell 7.0 Hurdles To ABENOMICS 8.0 Japans Ageing Population Problem 8.1 Japans Economic Data 9.0 Why Did Greece Sink and Japan Still Sails

- 3. INTRODUCTION TO THE ECONOMY OF JAPAN FUNDAMENTALS OF THE ECONOMY The economy of Japan is the third-largest in the world by nominal GDP and the fourth-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP) and is the world's second largest developed economy. According to the International Monetary Fund, the country's per capita GDP (PPP) was at $37,519, the 28th highest in 2014, down from the 22nd position in 2012. Japan is a member of the G7. Nikkei 225 presents the monthly report of top Blue chip (stock market) equities on Japan Exchange Group. Due to a volatile currency exchange rate, Japan's GDP as measured in dollars fluctuates widely. Accounting for these fluctuations through use of the Atlas method, Japan is estimated to have a GDP per capita of around $38,490.

- 4. Japan is the world's largest creditor nation as well as having the highest ratio of public debt to GDP. Japan generally runs an annual trade surplus and has a considerable net international investment surplus. As of 2010, Japan possesses 13.7% of the world's private financial assets (the third largest in the world) at an estimated $13.5 trillion. As of 2015, 54 of the Fortune Global 500 companies are based in Japan, down from 62 in 2013. ECONOMIC HISTORY OF JAPAN Pre-war period (1868–1945) Since the mid-19th century, after the Meiji Restoration, the country was opened up to Western commerce and influence and Japan has gone through two periods of economic development. The first began in earnest in 1868 and extended through to World War II , the second began in 1945 and continued into the mid- 1980s. Economic developments of the Pre-war period began with the “Rich State and Strong Army Policy” by the Meiji government. During the Meiji period (1868– 1912), leaders inaugurated a new Western-based education system for all young people, sent thousands of students to the United States and Europe, and hired more than 3,000 Westerners to teach modern science, mathematics, technology, and foreign languages in Japan (Oyatoi gaikokujin).

- 5. The government also built railroads, improved road, and inaugurated a land reform program to prepare the country for further development. To promote industrialization, the government decided that, while it should help private business to allocate resources and to plan, the public sector was best equipped to stimulate economic growth. The greatest role of government was to help provide good economic conditions for business. In short, government was to be the guide to producer for flourishing business. In the early Meiji period, the government built factories and shipyards that were sold to entrepreneurs at a fraction of their value. Many of these businesses grew rapidly into the larger conglomerates. Government emerged as chief promoter of private enterprise, enacting a series of Pro-business policies. In the mid-1930s, the Japanese nominal wage rates were 10 times less than the one of the U.S (based on mid-1930s exchange rates), while the price level is estimated to have been about 44% the one of the U.S. Post-war period (1945–present) From the 1960s to the 1980s, overall real economic growth was extremely large: a 10% average in the 1960s, a 5% average in the 1970s and a 4% average in the

- 6. 1980s. By the end of said period, Japan had moved into being a high-wage economy. Growth slowed markedly in the late 1990s also termed the Lost Decade after the collapse of the Japanese asset price bubble. As a consequence Japan ran massive budget deficits (added trillions in Yen to Japanese financial system) to finance large public works programs. By 1998, Japan's public works projects still could not stimulate demand enough to end the economy's stagnation. In desperation, the Japanese government undertook "structural reform" policies intended to wring speculative excesses from the stock and real estate markets. Unfortunately, these policies led Japan into deflation on numerous occasions between 1999 and 2004. In his 1998 paper, Japan's Trap, Princeton economics Professor Paul Krugman argued that based on a number of models, Japan had a new option. Krugman's plan called for a rise in inflation expectations to, in effect, cut long-term interest rates and promote spending. Japan used another technique, somewhat based on Krugman's, called Quantitative easing. As opposed to flooding the money supply with newly printed money, the Bank of Japan expanded the money supply internally to raise expectations of inflation.

- 7. Initially, the policy failed to induce any growth, but it eventually began to affect inflationary expectations. By late 2005, the economy finally began what seems to be a sustained recovery. GDP growth for that year was 2.8%, with an annualized fourth quarter expansion of 5.5%, surpassing the growth rates of the US and European Union during the same period. Unlike previous recovery trends, domestic consumption has been the dominant factor of growth. Despite having interest rates down near zero for a long period of time, the Quantitative easing strategy did not succeed in stopping price deflation. This led some economists, such as Paul Krugman, and some Japanese politicians, to advocate the generation of higher inflation expectations. In July 2006, the zero-rate policy was ended. In 2008, the Japanese Central Bank still had the lowest interest rates in the developed world, but deflation had still not been eliminated and the Nikkei 225 had fallen over approximately 50% (between June 2007 and December 2008). However, on April 5, 2013, the Bank of Japan announced that it would be purchasing 60-70 trillion yen in bonds and securities ( Quantitative Easing ) in an attempt to eliminate deflation by doubling the money supply in Japan over the course of two years. Markets around the world have responded positively to the government's current pro-active policies, with the Nikkei 225 adding more than 42% since November 2012. The Economist has suggested that improvements to bankruptcy law, land

- 8. transfer law, and tax laws will aid Japan's economy. In recent years, Japan has been the top export market for almost 15 trading nations worldwide. JAPANS ECONOMIC MIRACLE The Japanese economic miracle was Japan's record period of economic growth between post-World War II era to the end of Cold War. During the economic boom, Japan rapidly became the world's second largest economy (after the United States) by the 1960s. In the Lost Decade of the 1990s, however, it suffered its longest economic stagnation since World War II. This economic miracle was the result of Post-World War II Japan and West Germany benefiting from the Cold War. It occurred partly due to the aid and assistance of the U.S., but chiefly due to the economic interventionism of the Japanese government. After World War II, the U.S. established a significant presence in Japan to slow the expansion of Soviet influence in the Pacific. The U.S. was also concerned with the growth of the economy of Japan because there was a risk after World War II that an unhappy and poor Japanese population would turn to communism and by doing so ensure that the Soviet Union would control the Pacific. The distinguishing characteristics of the Japanese economy during the "economic miracle" years included: the cooperation of manufacturers, suppliers, distributors,

- 9. and banks in closely knit groups called keiretsu; the powerful enterprise unions and shuntō, good relations with government bureaucrats, and the guarantee of lifetime employment (Shūshin koyō) in big corporations and highly unionized blue-collar factories. This economic miracle was spurred mainly by Japanese economic policy, in particular through the Ministry of International Trade and Industry. ANALYSIS OF THE JAPANESE DEBT PROBLEM With low unemployment and high labor force participation, Japan has essentially no idle resources. The scope for boosting the economy with fiscal stimulus or easy money is almost nil. But Japan continues to run an enormous budget deficit every year. In 2014, the government had a deficit of 7.7 percent of gross domestic product, with a primary deficit -- which excludes interest payments -- of just under 6 percent. Things are looking somewhat better for 2015. A hike in the consumption tax in 2014 has swelled revenues. Government coffers have also been boosted by increased profits at Japanese companies -- which is then subject to the country's high corporate tax rate. As a result, the primary deficit is projected to be only about 3.3 percent in 2015.

- 10. But 3.3 percent is still way too high. In the long run, any deficit that stays higher than the rate of nominal GDP growth is unsustainable. Japan's nominal GDP growth is now about zero. Its long-term potential real GDP growth is no more than 1 percent (due to shrinking population), and the Bank of Japan has not managed to increase core inflation to the 2 percent target despite Herculean efforts. Even if interest rates stay at zero forever -- allowing the country to eventually refinance all its debt in order to bring interest payments down to zero -- borrowing 3.3 percent of GDP every year is just too much. And if interest rates rise, deficits would explode. The government, of course, knows this, and has pledged to cut the primary deficit to 1 percent by 2018 and to zero by 2020. But its projections rely on unrealistic fast growth assumptions; it would require Japan to expand well above its long-term potential rate. As in the U.S., Japanese administrations are in the habit of over-optimism. The Ministry of Finance, full of sober-minded bureaucrats, projects that under more realistic growth assumptions, the primary deficit will shrink only to 2.2 percent. Even that improvement would require tax hikes, spending cuts or some combination of the two. A primary deficit of 2.2 percent would be at the very edge of long-term sustainability. If we assume a 1 percent real potential growth rate and 1.5 percent inflation, then a 2.2 percent deficit will be just barely under the maximum sustainable level of 2.5 percent. So Japan does have a chance to avoid disaster. But the risk is still high. A growth slowdown, a rise in interest rates or a fall in corporate profitability could easily

- 11. nudge the government back to excessive debt growth. A secure future will require more serious deficit reduction. That will mean either spending cuts or tax increases. Tax hikes hurt the economy, in the short term by damping demand and in the long term via economic distortion. Spending cuts are a better bet, but there's a big political impediment. Japan's society aging and shrinking, and an ever-greater share of spending goes to pensions and other transfer payments to the old. The elderly are numerous and they vote in great numbers, so there is little scope for cutting their payouts. Unless there is an attitude change -- an increased willingness by the baby boom generation to make sacrifices for the good of the country -- the government will probably continue to support the boomers at the expense of Japan's beleaguered millennials. It looks as if tax hikes are the only way to bring the deficit down to sustainable levels. At some point no one knows quite when a primary deficit at current levels will lead either to a default or to direct monetary financing, with the central bank printing money to buy new government debt issues. Direct monetary financing will lead eventually to hyperinflation, which acts much like a total default on all public and private debts. Either a default or a hyperinflation would cause every Japanese financial institution, and most Japanese businesses, to fail. Maybe Japan would be OK, since it wouldn't owe very much to foreigners -- most of Japan's debt is domestically financed. Businesses would eventually reorganize, new financial institutions would emerge to lend them money and workers would find something to do. But the disruption to economic life would be so huge that it might put the country in

- 12. danger of an extremist takeover probably by right-wing elements, since Japan lacks a powerful left wing. An extremist regime would probably wreck the economy with bad policy, pushing Japan out of the ranks of rich developed countries. If all goes perfectly, Japan can avoid this kind of nightmare scenario. But it’s far from a sure thing. More measures are needed. Spending cuts, especially on transfers to the elderly, would be ideal, but tax hikes may be the only way. Japan Government Debt to GDP 1980-2016 Japan recorded a Government Debt to GDP of 229.20 percent of the country's Gross Domestic Product in 2015. Government Debt to GDP in Japan averaged 123.60 percent from 1980 until 2015, reaching an all time high of 229.20 percent in 2015 and a record low of 50.60 percent in 1980. Government Debt to GDP in Japan is reported by the Ministry of Finance Japan.

- 13. WHY JAPANS DEBT TO GDP RATIO DETERIORATED There are two main reasons: Economic Stagnation Demographics. Since the mid-1990s, deflation has really hurt Japan’s economy. With deflation, nominal GDP – GDP that has not been adjusted for inflation – stagnates or even shrinks, and tax and other government revenues depend on the size of nominal GDP. Stagnation reduces corporate taxes and government revenues. Moreover, Japan made several policy mistakes. In 1997, the government raised its consumption tax to 5 per cent from 3 per cent, believing that recovery was around the corner, but the move proved premature and backfired. And in 2000, the Bank of Japan terminated its zero-interest-rate policy before Japan overcame deflation. Japan’s famously aging population translates into increasing pension, medical and elder-care expenditures. This is a long-term problem, but related to the economy. When people retire or are unemployed many households stop making contributions to the pension system, while the government has to pay the benefits. The widening gap has been compensated for by government borrowing.

- 14. During almost two decades of deflationary stagnation, Japan has recorded an average annual nominal growth rate of 1 per cent, which is dismal. But deflation can be overcome, as the current government and the Bank of Japan are attempting to do. Despite a setback caused by a consumption tax hike in 2014, tax revenue for that fiscal year increased by 12.3 per cent over the previous year, reaching its highest level since 2008. By going back to the normal nominal growth rate at the level of other advanced economies, Japan can put its fiscal house in order. In short, Japan can still pay its debt by overcoming deflation and resuming economic growth.

- 15. Generally, Government debt as a percent of GDP is used by investors to measure a country ability to make future payments on its debt, thus affecting the country borrowing costs and government bond yields. This page provides the latest reported value for - Japan Government Debt to GDP - plus previous releases, historical high and low, short-term forecast and long-term prediction, economic calendar, survey consensus and news. Japan Government Debt to GDP - actual data, historical chart and calendar of releases - was last updated on July of 2016. Japan is heading for a full-blown solvency crisis as the country runs out of local investors and may ultimately be forced to inflate away its debt in a desperate end- Japan Government Last Previous Highest Lowest Unit Government Debt to GDP 229.2 226.1 229.2 50.6 percent Government Budget -6.00 -7.1 2.58 -8.9 percent of GDP Government Budget Value 64165 -66827 76276 -347513 JPY HND Million Government Spending 104816.4 104052 104816.4 41526.6 JPY Billion Credit Rating 77.62 Military Expenditure 46345.8 45866.8 47576.5 39104.2 USD Million Asylum Applications 773 773 773 23 Persons Government Spending To GDP 42.1 42.5 42.5 35.9 percent

- 16. game. Zero interest rates have disguised the underlying danger posed by Japan’s public debt, likely to reach 250pc of GDP this year and spiralling upwards on an unsustainable trajectory. To our surprise, Japanese retirees have been willing to hold government debt at zero rates, but the marginal investor will soon not be a Japanese retiree. the Japanese treasury will have to tap foreign funds to plug the gap and this will prove far more costly, threatening to bring the long-feared funding crisis to a head. Analysts say this would transform the country’s debt dynamics and kill the illusion of solvency, possibly in a sudden, non-linear fashion. Bank of Japan will come under mounting political pressure to fund the budget directly, at which point the country risks lurching from deflation to an inflationary denouement. One day the BoJ may well get a call from the finance ministry saying please think about us – it is a life or death question - and keep rates at zero for a bit longer. The risk of fiscal dominance, leading eventually to high inflation, is definitely present. I would not be surprised if this were to happen sometime in the next five to ten years. Arguably, this is already starting to happen. The BoJ is soaking up the entire budget deficit under Governor Haruhiko Kuroda as he pursues Quantitative Easing. The central bank owned 34.5pc of the Japanese government bond market as of February, and this is expected to reach 50pc by 2017. Japanese officials admit privately that a key purpose of ‘Abenomics’ is to soak up the debt and avert a funding crisis as the big pension funds and life insurers retreat from the market. The other unstated goal is to raise nominal GDP growth to 5pc in order to ‘bend down’ the trajectory of the debt ratio, a task easier said than done.

- 17. Once markets begin to suspect that Tokyo is deliberately engineering an escape from its $10 trillion public debt trap by means of an inflationary ‘stealth default’, matters could spin out of control quickly. It might lead to an abrupt reappraisal of sovereign debt risk in other parts of the world, especially in Europe with its own Japanese pathologies of low-growth and bad demographics. Roughly $7 trillion of debt is trading at negative yields worldwide, an accident waiting to happen for the bond market. The European Central Bank would be legally prohibited from activating its back-stop mechanism (OMT) to prevent yields soaring since these governments would not be in compliance with EU rules. Some of them have very high debt and presumably would have to default. The worry is what will happen in the next global downturn – or when the effects of cheap oil and quantitative easing fade – given that public finances are already

- 18. so stretched.One thing he is not worried about is running out of monetary ammunition. There is an argument that QE actually becomes more effective, the more you use it. As a central bank buys more bonds, the more it has to pay to convince the last hold-outs to sell their holdings. The effect on the price plausibly becomes stronger and stronger. The authorities should stick to plain vanilla QE rather than experimenting with “exotic stuff”. It makes little difference whether spending is paid for with money or bonds when interest rates are zero. Negative interest rates – or NIRP – have complex side-effects and damage the banks, which can’t pass on the rates to depositors. Banks are already in enough trouble without adding this one. JAPANS EXPERIMENT WITH RATES LESS THAN ZERO There are two interesting and important questions here. The first is “Why is Japan doing this?” The second is “How low can rates go?” Let’s talk about the second question first. There’s real uncertainty about how far below zero a central bank can push nominal interest rates using standard techniques like asset purchases. If holding your money in a bank account or government bond causes its value to steadily shrink, you can just withdraw your

- 19. money and put it in cash, hide it under your pillow or bury it in the back yard. I can almost guarantee you that somewhere in Japan, someone is doing this right now. One solution is simply to put a tax on paper cash. This is the solution being promoted by University of Michigan economist Miles Kimball, who has been going around the world evangelizing for electronic money for years now. The University of Chicago’s John Cochrane is skeptical, pointing out other ways that savers could avoid losing money to negative rates. But most of these techniques rely on prepaying bills, which could be penalized more under an electronic money system. Now it's true that -0.1 percent isn't very much below zero, so there won’t be a huge flight to cash just yet. But if the BOJ decides to send rates deeper into negative territory, expect to see something like Kimball’s electronic money system. Let’s think about why the BOJ made this move right now. One reason might be that since the spring of 2015, Japan’s core inflation rate has tumbled back to about zero. If the BOJ takes its official 2 percent inflation target seriously, it might be implementing negative rates in order to hit the target. But if this were the main motivation, it’s coming a bit late, since inflation collapsed almost a year ago. A more likely explanation is that the BOJ is trying to cancel out some negative demand shocks. One big such shock is the China slowdown, which is already hurting Japan’s trade in a big way.

- 20. A second hit to demand will come if the government decides to raise taxes again. A higher tax on consumption imposed in 2014 raised revenues and put Japan on a sounder long-term fiscal footing, though it probably hurt the economy temporarily. One or two more similar tax hikes might put Japan on the path to long-term fiscal sustainability. So adopting negative rates might be how the BOJ hopes to cancel out the hit to demand from these future taxes increases. A third reason for negative interest rates also involves fiscal issues. The lower rates go, the more cheaply the government can refinance its debt. Once all debt is refinanced at negative rates, the government’s interest payments vanish, allowing it to apply more taxes toward its spending commitments to the elderly. If the government can exercise fiscal restraint and resist the urge to splurge, then negative rates will act as a stealthy form of debt monetization. All of these challenges might eventually call for very negative rates. So it makes sense for the BOJ to test the waters now, by sending rates a little bit below zero. This will give the central bank an idea of how easy it is to push rates below zero with standard techniques, which will help inform it about when it might need to implement a Kimball-style electronic money system. In part, negative rates are an experiment. So what are the risks of negative rates? The obvious one is that at some point Japanese savers most of which are corporations at this point, since household savings have collapsed might start moving their money out of the country. Capital

- 21. flight would necessitate a rapid reversal of interest rates, and might even spur hyperinflation a run on the Japanese currency itself. But this danger is remote. And other dangers financial instability, for example -- are not even certain to exist. So far, low interest rates don’t seem to have done much harm to advanced economies, so it’s doubtful that slightly negative rates will be any different. If rates go very negative, though, things could abruptly change. The world’s central banks are, after all, in uncharted territory here. ZERO RATES , ZERO SUCCESS Japan took a big risk in January. To stimulate its economy, it adopted an unconventional negative interest-rate policy that penalized banks for hoarding too much money. The move has been an all-out failure. Not only has Japan drawn the ire of chief executives and bankers at home and abroad, but the nation hasn't achieved its objective. For evidence of this, take a look at bond yields. They have plunged to unfathomable lows, with rates on 40-year Japanese bonds falling to a record low of 0.3 percent, fueling gains of 4.3 percent on Japanese sovereign debt generally since the end of January. This isn't entirely unexpected. But these diminishing

- 22. yields haven't prompted investors to buy riskier assets, such as Japanese stocks. In fact, the Nikkei 225 lost 6.4 percent from the end of January through April 18. The Nikkei did rally this week but it wasn't because of the stimulus announced earlier this year. Rather, the gain was due largely to a better macroeconomic outlook and the possibility that Japan could expand its asset-purchase program as soon as next week.) You would think that investors would want to be compensated more than 0.3 percent for four decades, or look elsewhere instead of paying to lend to Japan for as much 10 years. But they're still buying bonds and don't seem to believe in the nation's future growth prospects. This is different from what happened in the

- 23. U.S., where stocks often rallied after the Federal Reserve announced new stimulus measures. The yen has also been a huge surprise in the aftermath of Japan's negative-rate announcement, on Jan. 29. Rather than weaken, the currency has strengthened against the dollar. This doesn't necessarily make sense because ordinarily an ultra-easy monetary policy should spur inflation and prompt residents to take money out of the country, which should weaken the yen. The Japanese currency has strengthened about 3 percent against the dollar.

- 24. But inflation is moribund, as is Japan's annual economic output. Expectations don't seem to be rising all that fast, either, given the rates that bond investors are willing to accept at this point. Diminishing Returns Japan's economy isn't seeing much of a boost from its stimulus. Deflated Future Five-year, five-year yen inflation swap rate

- 25. Even Japanese banks don't seem to be in a hurry to lend. They've actually been slowing the pace of loan growth of late, despite being penalized for holding excess cash with the Bank of Japan. RISING LOANS Year-over-year growth of loans outstanding in Japan.

- 26. Maybe things will change and history will show these unconventional policies were ultimately effective. But right now, it sure doesn't look like that way. ANALYSIS OF THE ECONOMICAL AND DEMOGRAPHIC ISSUES AND EFFECTS OF QUANTITATIVE & QUALITATIVE EASING

- 27. According to conventional economic theory, the monetisation of government debt is a recipe for fiscal profligacy and hyperinflation. It should be the last thing any credible central bank turns its hand to. But this is precisely what the Bank of Japan has been doing for the past three years. As part of its quantitative and qualitative monetary easing (QQE), the BoJ has already amassed more than ¥300 trillion ($3.5 trillion) of Japanese government bonds. The bank has pledged to continue this gigantic monetary easing program until the rate of inflation rises to 2 per cent. But on Friday it shifted course to also embrace a policy of limited negative interest rates. According to the BoJ, the Japanese economy is trapped in a vicious cycle of deflation and stagnation – escaping from this requires bold attempts on both monetary and fiscal fronts. QQE is an integral part of Abenomics, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's comprehensive economic revitalisation package. But the idea that Japan needs a radical policy to break out of its deflationary malaise is questionable. It is hard to believe that Japan's deflation is so bad that the BoJ has been licensed to engage in a policy that openly challenges basic economic theory. Not only has Japan's deflation been quantitatively miniscule – the average inflation rate for the past 15 years is -0.1 per cent – but much of this deflation is a statistical illusion. Japan's consumer price statistics tend to overestimate quality improvement in new products, which has the effect of dampening the official rate of inflation.

- 28. According to periodic surveys conducted by the BoJ and the Cabinet Office, the average Japanese consumer doesn't expect the general price level to decline in the future, a fact conveniently ignored by both the BoJ and the Abe administration. Japan's so-called "lost decades" have not been as miserable as is often presumed. Admittedly, the growth rate of Japan's GDP did fall considerably in the 1990s and is now close to the bottom of those of industrial countries. But a substantial part of this growth deceleration can be explained by a shrinking labour force and falling average working hours. The growth rate of Japan's GDP per labour hour is still above the average for the G7 countries, casting doubt over the view that the Japanese economy is seriously underperforming its potential. Since Japan's total labour inputs are expected to decline at an even faster pace in the future, it would be unwise to pursue overly ambitious GDP growth, though this is exactly what is being done by the Abe administration. One might still argue that QQE is desirable because a small amount of inflation helps the economy run smoothly. But according to Japan's consumer price data, the relative prices of individual goods and services become noticeably unstable as the headline inflation rate rises above a few per cent. This implies that a reflationary policy is risky unless the BoJ is capable of keeping the inflation rate at or near its target level. But for the central bank to control inflation, it must be able to control the quantity of money. In the context of the BoJ's ongoing policy, this means disposing of a

- 29. massive number of Japanese government bonds in a fairly short period of time. Doing so is possible only if the government is unquestionably solvent; otherwise private investors refuse to buy back government bonds, triggering a sovereign debt crisis. Unfortunately the solvency of the Japanese government is increasingly in doubt. Not only is Japan's public debt staggeringly large – it now exceeds 240 per cent of its GDP – but the government is incurring massive fiscal deficits each year. Worse yet, these deficits are often more structural than cyclical, reflecting Japan's ballooning social security expenditure. Japanese society is ageing rapidly. Reducing social security programs, such as pensions and elderly care services, would be economically difficult and politically suicidal. The Abe administration is making use of a temporary increase in tax revenue not to retire existing debt, but to increase expenditure on services benefiting the elderly. Japan has a very high debt to GDP partially because it has attempted to use fiscal stimulus (i.e. paving roads) to jump start its economy over the last two decades. In addition, up until this point most Japanese Government Bonds (about 90%) are held by citizens of Japan, and this has allowed it to take advantage of extremely low interest rates. Low interest rates mean that Japan does not have very high interest payments in relation to it's level of debt. For now, then, Japan will not default like Greece whose debts are held by external creditors and who cannot print their own money to finance their debt because they are part of the Euro zone.

- 30. The future of Japanese debt is murky. Japan faces very significant structural headwinds as it tries to keep it's debt under control. The two factors which are likely to most significantly impact the Japanese ability to repay its debts in the future are it's demographics and it's economic growth. Japanese economic growth in an absolute sense has been fairly low for almost two decades now. This means that the GDP part of the debt to GDP ratio is not growing particularly fast. Many economies hope that they can grow their way out of their debt, but it's unclear whether Japan can accomplish this. Perhaps even more serious is the Japanese demographic situation. The Japanese population peaked in 2010 and is now declining. In addition, an increasing proportion of its population is elderly. This, of course, means fewer working age people which means more difficulty growing GDP. More significantly, though, this also means that there are fewer people to finance Japan's massive debt within the country. In particular, much of Japan's debt is financed through Japanese citizens' savings which are channeled through things like pension funds and life insurance. As a culture, Japan is extremely conservative and insular when it comes to money. This tendency means that significant amounts of savings are channeled into Japanese debt. As the Japanese populace ages, people are going to start withdrawing from these funds making it increasingly difficult to finance the debt within the country. At the same time, the savings rate for younger people in Japan is also falling indicating that the fewer younger people in Japan will also not be contributing as much per person to financing the Japanese debt as in the past. Instead, Japan will have to venture out into the broader world in order to roll over it's massive debt.

- 31. This is likely a gradual process, but it seems likely that at some point enough debt will be held by non-Japanese citizens that Japanese Government Bonds will become susceptible to interest rate fluctuations similar to many other countries. At that point, Japan may start having difficulties paying back it's debts. Japan is currently embarking on a monetary program to try and jump-start it's economy and combat it's debt problem through growth. The Japanese central bank is essentially printing massive quantities of money and purchasing Japanese Government Bonds in a bid to increase inflation and spur growth. Currently, it has had a significant effect in lowering the value of the Japanese Yen on the international market. While this has helped large firms which primarily export, it has hurt small and medium sized firms by raising their costs. While it has lowered the value of the Yen, this program has not had as significant effect on inflation as desired. At the same time, Japan has failed to implement any type of fiscal discipline. Over the last twenty years, asset prices are down by 65% for the Nikkei stock index, 50% for residential real estate, and 70% for commercial real estate. The centrally planned Japanese government responded to this crisis of falling asset values with wave after wave of colossal deficit spending stimulus. Japan’s public debt rose from virtually nothing to 225% of gross domestic product, but the economy has remained stagnant. Japan is sitting on central government debt approaching one quadrillion (one thousand trillion) Yen and central government revenues are approx ¥48 trillion. Their ratio of central government debt to revenue is a fatal 20x. Both Japan and the USA need interest rates to stay low to fund their enormous deficits. According to J. Kyle Bass’ Hayman Capital, every 100 basis point

- 32. change in the weighted-average cost of capital (interest rates) is roughly equal to 25% of Japan’s central government’s tax revenue. Put another way, a 200 basis point move higher over time in Japan’s interest rates will increase their interest expense by more than ¥20 trillion. If Japan had to borrow at France’s rates (a AAA-rated member of the U.N. Security Council), the interest burden alone would bankrupt the island nation. Japan has engaged in about the same level of 7% deficit spending as the US has averaged for the last two years, except Japan has sustained this level of spending for the last twenty years. Normally, heavy deficit spending quickly exhausts a nation’s internal markets to buy its own debt and the country is forced to auction bonds at higher and higher interest rates to outsiders; which also increases the costs of the debt and forces the nation to sell even more debt. At some point the country becomes so indebted that credit agencies downgrade the country’s quality rating to junk, foreigners refuse to buy new debt, and the country defaults. Japan has avoided this deficit financing end-game, because the nation has been able to finance 95% of its debt at home. Over the last year Greece with a third less and Ireland with less than half the debt to GDP ratio of Japan, imploded when foreigners refused to invest. In the USA we’re not that far behind. According to Congressional Budget Office data, every one percentage point move in the weighted-average cost of capital at the end of the day will cost the US $142 billion annually in interest alone. A move back to 5% short rates will increase annual US interest expense by approx $700 billion annually vs. current US government revenues of $2.228 trillion.

- 33. As deficit spending has remained extraordinarily high for such a long period, Japan has maintained a 41% corporate tax rate; the highest in the world, 10% above the US and Europe and triple the fast growing Asian economies of Taiwan and Singapore. This has made Japan an unattractive location for private investment. The complete lack job security for young workers who can only find temporary employment has made life difficult for new families and caused the birth rate for Japanese women to be cut in half. Lower family formation has caused the household savings rate for the thrifty Japanese to fall from 5% at the end of the 1990’s to just above 2% currently. Japan has maintained current-account surplus and has been sending more than 3% of its GDP abroad, providing more than $175 billion of funds this year for other countries to borrow. This paradox of a stunningly indebted nation financing the world is explained by a combination of high corporate saving and low levels of residential and non-residential fixed investment due to poor investment opportunities in Japan. That money is gone after this crisis. Millions of Japanese savers are about to start spending their savings on essentials, since they have lost their jobs and businesses due to the damage. Tokyo Electric Power Company will suffer losses of over $100 billion from its Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant melt-down and most of Japan’s northern corporate facilities that hug the eastern coastline have been destroyed or incapacitated. Japan averages one earthquake every four minutes, but Friday’s quake and tsunami were both the largest in the history of the country. Earthquake insurance in Japan is very expensive and only 10% of homeowners buy coverage.

- 34. Therefore, the Japanese government will be on the hook for several hundred billion in infrastructure and reconstruction costs. Many naive analysts are commenting about how this natural disaster will be good for the Japanese economy, because of the substantial rebuilding program. That might have been true if Japan was not already on the verge of a man-made debt disaster prior to this natural disaster. Standard & Poor’s credit rating service had just downgraded Japan’s sovereign debt to AA- in mid-January. The huge increase in the costs for welfare and unemployment payments, the economic disruption, the scale of the devastation, the lack of insurance and the minimum five years to rebuild the country may take Japan’s credit rating down to “junk bond” levels. The earthquake and tsunami that have devastated Japan came with quickly and violently. The debt crisis tsunami has been building for twenty years and may be much more devastating to the future of Japan. THE TRUTH BEHIND ABENOMICS .

- 35. There's a new government in Japan, and it appears determined to finally do "whatever it takes" to attempt to revive the moribund Japanese economy, which has struggled with deflation for a decade. The plan - called "Abenomics," named after newly-elected Prime Minister Shinzo Abe - is three-fold. It involves a massive increase in Fiscal Stimulus through government spending, a massive increase in Monetary Stimulus through unconventional Central Bank policy, and a reform program aimed at making structural improvements to the Japanese economy. In short, "Abenomics" amounts to one of the biggest economics experiments the modern world has ever seen. Financial markets are loving it. The Japanese stock market is soaring. But what exactly is it, and how is it expected to work? In a recent report, titled "Abenomics Handbook," Nomura economists led by Tomo Kinoshita break down the Japanese government's new plan and examine the challenges facing it. Naturally, the first question is: How exactly are these policies supposed to boost the economy? While fiscal stimulus and structural reform are essential components of the experiment, monetary policy is expected to do most of the heavy lifting in the short term. So, let's take a look at the monetary policy behind the plan first. THE MONETARY POLICY ASPECTS OF ABENOMICS

- 36. The goal of easy monetary policy is to reduce real interest rates. In Japan's case, it has a significant side effect of weakening the yen. So, the yen is weakening - and it's beginning its journey downward from incredibly elevated levels. (In recent years, investors piled into yen as a safe- haven currency, helping to drive up its value.) A weaker yen could be virtuous for the Japanese economy. The currency has already devalued swiftly against the dollar since September, when the wheels of a new economic regime in Japan were set in motion. This does a number of things. Most importantly, it boosts exports, because other currencies can now buy more Japanese-manufactured products. That means manufacturers are selling more, which feeds into corporate earnings and hopefully translates to increased business investment.

- 37. All of this should boost stock prices on a fundamental basis. At the same time, the weakening yen provides fuel for stocks. Since September, the Japanese government has verbally "talked down" the yen, and a big rally in the Nikkei materialized along with the decline of the currency. As for the specific effect of higher share prices on the economy, higher share prices invigorate corporate capex by – (1) Making it easier for companies to raise funds, and (2) Making companies more likely to invest in business expansion. We estimate that a 10 percent rise in share prices boosts CAPEX by 3.2 percentage points one year later." And the wealth effect is a big part of the plan.

- 38. For households, higher share prices stimulate willingness to spend by boosting the value of shareholdings and giving an indication of the health of the economy. A 10 percent rise in share prices boosts consumer spending by 0.12 percentage points three months later. All of this works to narrow the ¥16.5 trillion (~ $170 billion) gap between current GDP and Potential GDP, thus working toward eliminating deflationary pressures. However, the Japanese government has come under fire in the international community recently for its verbal interventions in the yen that have caused it to swiftly devalue against other currencies. The Bank of Japan has a few other options. Recently, it announced that it would double its target inflation rate to 2 percent, employing open-ended asset purchases (much like the Federal Reserve is doing in the United States) to get there. This represents a shift from the conservatism that has characterized the Bank of Japan in recent years. Haruhiko Kuroda, a big dove on monetary policy (meaning he's usually in favor of more stimulus, not less), is set to take over at the helm of the central bank in April. The times are changing, and one can expect to see some experimentation in the months and years ahead. THE ABENOMICS APPROACH TO FISCAL POLICY The second part of the "Abenomics" game plan involves short-term fiscal stimulus. This aims to revive economic growth immediately through increased government consumption and public works investment.

- 39. Abe already introduced ¥5.3 trillion (~ $60 billion) in public works spending as part of its 2013 budget. That's up from an estimated ¥5 trillion (~ $50 billion) last year, according to Nomura, representing a change from the fiscal tightening that Japan has undergone in recent years. Aside from the general account, the government plans to set aside spending for post-quake reconstruction efforts in special accounts. "The Abe government has decided to boost total spending on the five-year effort (through FY15) to about ¥25 trillion (~ $260 billion), from ¥19 trillion (~ $200 billion) previously." The important point here is that the government is pledging to be flexible with regard to fiscal policy in the coming years, a stance in stark contrast to those in the United States (which is dealing with the effects of sequestration) and the EURO area (where economic austerity is helping to deepen the economic contraction there). STRUCTURAL REFORMS Loose fiscal and monetary policy is supposed to facilitate expansionary economic conditions in the short term (although weakening the yen is arguably a longer- term goal as well). Crucially, though, the success of "Abenomics" hinges on the third prong of the approach: structural reform. This is the key to improving medium-term growth potential, details of which are expected to be unveiled to the public in June.

- 40. "With government debt having expanded to more than 200 percent of GDP, we think it will be difficult for Japan to boost the economy in the medium term via fiscal spending alone. "As the effects of bold monetary easing are primarily transmitted via expectations on the financial and capital markets, any resultant move out of deflation is likely to be short lived unless economic growth can also be boosted via the government's growth strategy." Below is a summary of the growth strategy currently under proposal.

- 41. There are several aspects to the regulatory reforms under proposal as well, outlined below. In short, there is a lot of work to do.

- 42. Will the Abe government be able to get it all done? There are some serious open questions about its ability to achieve success in putting the Japanese economy back on stronger footing.

- 43. ABENOMICS IN A NUTSHELL

- 44. HURDLES TO ABENOMICS The first question is whether the Bank of Japan will be able to implement monetary policy to actually effect 2 percent inflation. After all, they've been operating with a 1 percent inflation target, and they haven't even been able to come close to that. Attainment of the 2 percent inflation target will be problematic, I see the establishment of the 2 percent inflation target as meaningful because setting the bar high and bringing on board more powerful easing measures makes an end to deflation more likely. The risks to financial stability may arise from excessive monetary easing, warning that if the BOJ were to sharply increase its purchases of financial assets, this could cause distortions in the markets for those financial assets, disrupting market mechanisms or producing unforeseen risks related to the accumulation of imbalances. In other words, there could be bubble trouble. The Abe government's fiscal approach is tricky, too. Good policy strives to be counter-cyclical, meaning that when the economy improves, the government should take the opportunity to tighten its belt. There's a consumption tax hike scheduled for 2014, though. Nomura thinks the Abe government will boost spending to offset it.

- 45. "The biggest challenge," the economists say, "is striking a balance with fiscal reconstruction." Abe's government says it wants to cut the budget deficit in half from 2010 levels by 2015 and flip the budget balance into outright surplus by 2020. Continued public spending could make that pretty difficult. Finally, if the yen stops weakening, it really puts the brakes on the entire "Abenomics" project. The yen is expected to continue its decline – and many expect the U.S. dollar to enter a new bull market - but, as ever, the future is uncertain, and for Japan, it depends on implementation. We should also note that this all assumes that the Abe government is committed to the task to begin with. There is at least one theory that ultimately calls this commitment into question.

- 46. CONCLUSION : Yen depreciation benefits exporters but it could also have an adverse effect on the economy via an expansion of the trade deficit or a deterioration in the terms of trade (export prices/import prices). Also, the benefits of fiscal expansion and monetary easing are not limitless. In particular, fiscal and monetary easing are not limitless. In particular, fiscal expansion could stimulate market concerns regarding problems securing funding and fiscal risk. For Japan's economy to overcome these challenges and be revived, we think the key requirements are a change in ingrained expectations about deflation (ie, an improvement in growth expectations), a self-sustaining increase in private-sector economic activity (i.e. growth without fiscal expansion), and fiscal reconstruction (i.e. easing of fiscal risk). If companies can pass higher import prices and other cost increases onto selling prices, we think restructuring pressures in Japan will lessen. If confidence in economic growth in Japan grows simultaneously with an improvement in Japan grows simultaneously with an improvement in corporate earnings, we think increases in employment and wages will be likely. If real wages increase amid efforts to end deflation and put inflation on track, we think the Japanese economy will be more likely to return to self-sustaining growth. The rest of the world will be watching closely.

- 47. JAPANS AGEING POPULATION PROBLEM Japan's total population peaked in 2008 at the 128 million mark and is forecast to slump to about 90 million by 2050. Moreover, the working population of people in the 15 to 64 age group peaked between 1990 and 1995 at some 68 per cent of total population. It now sits at 62 per cent. At the same time the proportion of people over 65 has risen from about 14 per cent to 24 per cent of the population. By 2050 the over 65s will be 40 per cent of the total population. These numbers are frightening. In its 18 years of a shrinking working population and deflation, Japan's government has tried to stimulate economic growth by running massive fiscal deficits and printing yen. It invented quantitative easing (QE) and despite QE's ineffectiveness, the move has been copied in the US, Britain and more recently the European Union . Today, Japan has the largest fiscal deficit of any developed country sitting on 230 per cent of gross domestic product. This addiction to debt has been funded by high levels of domestic savings. From the 1970s to the 1990s the average Japanese citizen saved about 15 per cent of income, making it possible for the government to keep racking up deficits year in year out.

- 48. Critically, these dynamics are about to change. With the Japanese population growing older at a rapid clip, private savings have fallen to just 3 per cent of incomes and by 2015 people are forecast to start dipping into their savings. Abe is acutely aware of this situation and is desperate to crank up the economy to offset this pending disaster. The US based investor Kyle Bass and the Harvard economist Martin Feldstein have both warned about the perils of Abe's policies. They believe targeting 2 per cent inflation will drive Japanese interest rates higher, making it near impossible for the government to meet its debt funding. At present, the interest bill on the government debt eats up 25 per cent of all tax receipts. A spike in interest rates would send this percentage soaring. Bass claims Abe is not helping the economy out of its funk but simply bringing forward the day of reckoning when the Japanese government defaults on its debt. Abe's bold attempt to avert disaster must be closely analysed by investors and public officials. Australia's median age is about 38 years but forecasts put this number at 45 years, the same as Japan, somewhere between 2040 and 2050. The US is in a slightly better position but is heading down the same path, while the main European countries are only a decade behind Japan. Australia must not go down the same path as Japan of trying to prop up economic growth via an expansionary fiscal policy. As a nation it must continue to replenish the working population and try to keep it in the realms of 65 per cent of the overall population. Otherwise, it will fall into the same trap as the Japanese and more recently the main European nations of increasing our fiscal deficit to maintain the standard of living while the private community saves for retirement.

- 49. Another important step for the domestic economy is to heighten productivity levels. Increased productivity allows economies to grow at healthy rates without putting upward pressure on inflation and avoids Keynesian-like intervention through regular government deficits. Japan Economy Data 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Population (million) 128 128 127 127 127 GDP per capita (USD) 46,440 46,792 38,187 36,373 32,484 GDP (USD bn) 5,939 5,971 4,863 4,622 4,117 Economic Growth (GDP, annual variation in %) -0.5 1.7 1.4 0.0 0.5 Domestic Demand (annual variation in %) 0.5 2.6 1.7 -0.1 0.1 Consumption (annual variation in %) 0.3 2.3 1.7 -1.0 -1.2 Investment (annual variation in %) 1.6 3.2 2.6 1.1 0.1 Exports (G&S, annual variation in %) -0.4 -0.2 1.1 8.3 2.7 Imports (G&S, annual variation in %) 5.9 5.3 3.0 7.2 0.2 Industrial Production (annual variation in %) -2.6 0.2 -0.6 2.1 -0.9 Retail Sales (annual variation in %) -1.0 1.8 1.0 1.7 -0.4

- 50. 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Unemployment Rate 4.6 4.3 4.0 3.6 3.4 Fiscal Balance (% of GDP) -9.5 -9.0 -8.5 -7.7 -6.7 Public Debt (% of GDP) 203 210 212 212 209 Money (annual variation in %) 3.2 2.6 4.2 3.6 3.1 Inflation Rate (CPI, annual variation in %,) -0.2 -0.1 1.6 2.4 0.2 Inflation Rate (CPI, annual variation in %) -0.3 0.0 0.4 2.8 0.8 Inflation (PPI, annual variation in %) 1.5 -0.9 1.3 3.2 -2.3 Policy Interest Rate (%) 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.10 Stock Market (annual variation in %) -17.3 22.9 56.7 7.1 9.1 Exchange Rate (vs USD) 76.96 86.75 105.3 119.7 120.3 Exchange Rate (vs USD, aop) 79.70 79.84 97.63 105.9 121.1 Current Account (% of GDP) 2.2 1.0 0.8 0.5 3.3 Current Account Balance (USD bn) 130 59.6 40.6 24.7 137 Trade Balance (USD billion) -32.7 -87.3 -117.5 -122.4 -23.3

- 51. WHY DID GREECE SINK AND JAPAN STILL SAILS Greece's debt is 161.3% of the GDP. Japan's is 226.1%. The biggest reason is that the Greek debt is in Euro, owed to international banks from the Netherlands and Germany, etc. vs. the Japanese debt is in its own currency. The U.S. has a debt to GDP ratio of 61%. A more relevant number is actually the debt-to-tax revenue ratio, since this is the cash flow that can be used to pay back the debt. In this case, Japan has a debt- to-tax revenue ratio of 900%, Greece 475%, and the U.S. 408%. For Japan and the U.S., the biggest debtor is its own people. So theoretically, both countries can inflate its way out of it pretty fast (i.e., just print some more money). Greece, on the other hand, can't do that. In addition, with a strong currency such as the Euro, Greece can't even export itself out of it. Everything it makes is too expensive. The tourist industry, the shipping industry, and a whole bunch of other domestic industries are dying, and they can't drop the price and make them competitive again.

- 52. Think about it - when you destroy the domestic industry, you also destroy the employment opportunities and the potential tax revenue from them. Greece ended up with an astronomical unemployment rate. When Japan was forced by the US to raise it's $ peg in 1998 from ~ 300 to ~ 100 Yuan, it stopped the Japanese export industry dead on its tracks. When the U.S. tried to force China to raise its (Yuan / $) conversion rate in 2005 - 2008, China pretty much denied this. This was really important for China to keep its export industry going. To-date the austerity program has devastated the Greek economy as much as the total defeat suffered by Germany in WWI. Yeah, it's that much! The IMF has a set formula for all debtor countries: Privatize your industries and cut your social programs. It's clearly not working for Greece! Greece does not hold its debts domestically, in a currency under its control. Most of its debts are owed to foreign lenders, and the Euro is not a currency that is under the sole control of Greece. Japan's debts are largely owed domestically, and Japan's currency is under Japan's sole control. Japan may well be in a debt crisis that is largely unrecognized, again because of the concentration of the debt within Japan's frontiers. Can Japan really keep

- 53. borrowing more and more money to keep its governmental functions going? At some point, there will be a limit that just cannot be breached.