A study on the genus Ruscus and its horticultural value

- 1. The Cambridge University Botanic Garden Undergraduate Certificate of Higher Education in Practical Horticulture and Plantsmanship A Study on the Genus Ruscus and its Horticultural Value Giulio Veronese Trainee Horticultural Technician 2014 – 2015

- 2. 2

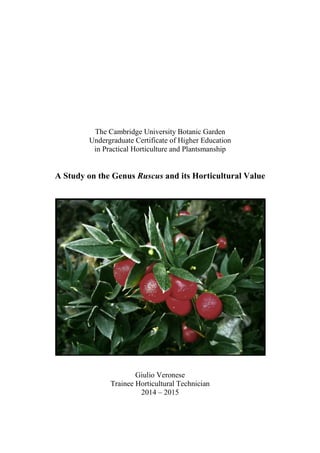

- 3. 3 The Cambridge University Botanic Garden Undergraduate Certificate of Higher Education in Practical Horticulture and Plantsmanship A Study on the Genus Ruscus and its Horticultural Value Giulio Veronese Trainee Horticultural Technician 2014 – 2015 Heu, patimur umbram Sundial motto © Giulio Veronese 2014 Printed: Le Cottage at the Cambridge University Botanic Garden, December 2014. Photographs by Abramo De Licio with the exception of the reproductions from CUBG Herbarium by Giulio Veronese, or where other source is given. Front cover photograph by Abramo De Licio, picturing Ruscus aculeatus at CUBG. Digital modification of pictures by Giulio Veronese.

- 4. 4

- 5. 5 Contents Introduction 7 Taxonomic and Evolutionary Overview 8 Significance in Morphological Botany 10 Ruscus: the Seven Taxa 12 Ruscus in Contemporary British Horticulture 18 Representation and Cultivation in the Cambridge University Botanic Garden 21 Conclusion 24 References 26 Acknowledgments 27

- 6. 6

- 7. 7 A Study on Genus Ruscus and its Horticultural Value Introduction An overview of the clade, family and subfamily is given, with attention in highlighting the continuous fluctuation in the taxonomy. The engaging case of the old Liliaceae family and its disputed taxonomic circumscription is discussed. The phylogeny and evolution of the group are also mentioned. Attention is then drawn into morphological botany, noticeably in describing the structure of cladodes. A comparison is made with the closely-related phylloclades and a theory raised on cladodes and phylloclades as very ancient structures adapted to dry conditions. Focus is gradually moved back to taxonomy with the description of the different taxa. The relevance of the work of Dr. Peter F. Yeo for the scientific recognition of the genus is stated for the first time. Thoughts of influential authors in the literature are reported, in order to demonstrate the changing fortunes of the genus in horticulture. The cornerstone thesis is introduced on Ruscus as a group of plants being not only botanically intriguing, but also having a great, unexpressed potential in horticulture. Firstly, their popularity in the British nurseries and gardens is investigated and data reported. Secondly, their potential is highlighted, especially by discussing the range of variation and adaptation within the taxa. The case of the National Collection of Ruscus at the Cambridge University Botanic Garden is described and the contribution of Yeo is recognised for the second time. Ideas are also suggested for maintaining, displaying and improving the living collection. Finally, conclusions are given and the principal idea of the use of Ruscus in modern horticulture restated. Studies on speciation and interbreeding programmes are suggested. A hypothesis is also raised that Ruscus may become more horticulturally important in view of probable climate change and water shortage. Horticultural display of Ruscus at the Cambridge University Botanic Garden

- 8. 8 Taxonomic and Evolutionary Overview The genus Ruscus is classified in the Asparagaceae family, subfamily Nolinoideae. Its taxonomic circumscription has long been a brain-teasing dilemma, the genus having fluctuated between different families and by turns located in Liliaceae, Convallariaceae and Ruscaceae. Ruscus was traditionally classified in the Liliaceae family, subfamily Asparagoideae. From its first description in 1789 Liliaceae has been a catch-all group containing all the left- overs from the lilioid and petaloid monocots which couldn’t fit in other families. Criteria included large flowers with parts in threes, three sepals and three petals arranged in two whorls, six stamens and a superior ovary. It was - blatantly - a too-broadly defined family, a sort of taxonomic “dustbin”, just like the old Scrophulariaceae and Ranunculaceae. Studies in the Eighties took the first steps towards the reorganisation of the relationships in the “lily-like monocots”. The process of splitting up the order Liliales started with the analysis of the patterning of the tepals and primarily with the discovery of phytomelan, a black pigment in the seed coat, which can be found only in Asparagales [Dahlgren et al., 1985]. A few years later, with the advent of modern taxonomic systems, genetic evidence confirmed what many had long suspected. Liliales was grossly polyphyletic and included a significant number of unrelated plants, which had evolved with considerable morphological diversity. The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group radically scrutinised circumscription of Liliales, transferring genera to several smaller families and many to other orders. Today the delimitation of Asparagales is circumscribed with DNA sequence analysis, but its exact morphological definition remains problematic, since its members are structurally very diverse. Most are herbaceous perennials, but climbers, small trees, succulents and geophytes are also present. Furthermore, no single morphological character appears to be diagnostic of Asparagales. Seed coat of Allium caerulum. The presence of the phytomelan crust in the outer epidermis indicates asparagalean delimitation [Tompkins County Flora, 2014] Phylogenetic cladogram showing the currently accepted circumscription of the old Liliales after the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group III system 2009 [Liliod Monocot, 2014]

- 9. 9 Taxonomists agree in dating Asparagales between 127 and 90 m.y.a., but divergence within Nolinoideae began circa 41-23 m.y.a., in the last part of the Paleogene period [The Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, 2014], making Ruscus a relatively young representative of the plant kingdom. However, even if Nolinoideae are the youngest branch in the monocotyledons, vegetative and floral variation is particularly impressive within the group. They range from herbaceous subshrubs, to succulent shrubs and trees, to tropical xerophytes and geophytes. This makes Nolinoideae a rather motley crew, with a high diversification rate and morphological variation even within the multi-branched and unpredictable group of Asparagaceae. These characters, together with the relatively recent evolution and branching of Asparagaceae, suggest that the exact delimitation of Nolinoideae and its full scientific understanding are still open to future study. Main phylogenetic tree of Asparagales. The diversification rate and branching within the clade is remarkable, probably the highest in monocotyledons together with Poales [The Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, 2014]

- 10. 10 Significance in Morphological Botany In Ruscus the apparent leaves are actually flattened modified stems, botanically referred to as cladodes. The flowers and subsequent fruits emerge directly from the cladodes, giving the plants their typical deceptive appearance. Cladodes are structures highly evolved for photosynthetic activity, substituting the function of the true leaves, which are either nonexistent or inconsequential and reduced to minute, scarious scale-like organs. In plant evolution, cladodes have been identified in fossils dating as early as the Paleozoic Era, circa 540-252 m.y.a. Cladodes are typical in Ruscus, Asparagus and Myrsiphyllum, all members of the Asparagaceae family. The Ruscus close relatives, Danae racemosa and Semele androgyna, are also cladode-bearing plants. In the case of Ruscus, cladodes bear the scale leaves as well as a subtended axillary bud on their surface, so resembling epiphyllous leaves. Their axillary origin and vertical instead of horizontal expansion also show the cauline nature of the cladodes. Flattened green stems in the axils of scale leaves. a) Asparagus densiflorus, b) Rhipsalidopsis rosea, c, c1) Semele androgyna, d, d1) Ruscus hypoglossum. Cl: cladode. Clcb: cladode condensed branching. Fp: flower pedicel. Ls: leaf spine. Pc: phyllocladode. Sl: scale leaf. St: stem. [Bell, 1991. Digitally-modified picture]

- 11. 11 Cladodes have limited growth, presenting stems consisting of one or two internodes and aborting apical meristems with no further development [Bell, 1991]. This morphologic behavior differentiates cladodes from phylloclades, similar structures consisting of a flattened stem representing a number of internodes, such as in Muehlenbeckia and Phyllanthus species or in some cacti, typically Opuntia. Phyllocladus, a genus of Australasian conifers, is also named after these structures, presenting lobed phylloclades that resemble pinnately compound leaves. Gray considers many cacti as condensed stems, “homologous with corms, tubers, &c., and similar in mode of growth, but above ground, and multiplying in the same ways” [Gray, 1880]. The green rind of the phylloclades performs the function of leaves, which are absent, transient or reduced to spines. This line of reasoning allows scope in discussing the condensed stems cladodes and phylloclades as linked forms of meristematic reorganisation adapted to dry climates. The subterranean situation is another parallel adaptation to the same conditions, as well as the tendency towards sclerophyllous tissues. In these extremely unfavourable habitats plants need to maximize their energy, developing skeletally essential structures. Leaf production becomes an unaffordable luxury as the stomatal conductance has to be reduced to the minimum. Cladodes of Ruscus x microglossus

- 12. 12 Ruscus: The Seven Taxa Ruscus produces sturdy but flexible shoots from below ground, renewing itself annually as typical in Asparagaceae. Plants spread with fleshy, stout rhizomes, similar to those of the related Convallaria majalis. They form dense patches which are tough to dig up and divide. Flowers are actinomorphic (as in all Nolinoideae) and inconspicuous, more or less horizontal or pendent in posture. They are produced one a time and last only a few days. The pollination mechanism is unknown. Flowers are visited by flies, but they have not been demonstrated to act as pollinators. The scarlet berries are spherical to ovoid, containing one seed. The evolutionary cradle is evidently the Mediterranean region, but the exact origin is difficult to localise because of the breakup of an initial homogenous population. There are also no fossil records, possibly due to the herbaceous nature of the plants or the fact that they grow in dry climates. The taxa probably evolved from a common ancestor, now extinct, and then migrated to their respective geographic areas [Yeo, 1968]. They are found from Madeira through southern Europe to Transcaucasia, and all live in thickets, dry banks and limestone, preferably under the protection of tree canopies. In horticultural literature, descriptions of Ruscus are a bit vague and circumspect. Authorities like Beth Chatto and Christopher Lloyd almost completely overlook the genus in their work. Other major authors describe the group as “strange, semi-shrubby plants” [Thomas, 1992], “shrub-like plants” [Grey-Wilson, 1993], “most unusual plants” [Junker, 2007] or “bushy shrublet” [Polunin et al., 1990]. Once again, one of the most enlightening observations comes from W.J. Bean, in his fundamental Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles: “Strictly speaking, the species of this genus should be regarded as shrub-like rather than true shrubs, none having really woody stems” [Bean, 1980]. Dr. Peter F. Yeo is the author of the chief work A Contribution to the Taxonomy of the Genus Ruscus, dated 1968. Yeo noted the several discrepancies in the scientific literature and the general failure to recognise the taxonomic situation within the genus. He defined the group as a family of “rhizomatous shrubs or perennial herbs” [Yeo, 1968] and divided it into the two series Ramosae and Simplices. His Contribution reinstated the genus its botanical importance and location in the modern taxonomy, defining the classification in seven taxa which is currently accepted. - R. aculeatus L. 1753 - R. colchicus Yeo 1966 - R. hypoglossum L. 1753 - R. hypophyllum L. 1753 - R. hyrcanus Woronow 1907 - R. x microglossus Bertol. 1857 - R. streptophyllus Yeo 1966 [The Plant List, 2014] Dr. Peter Frederick Yeo posing for the staff photo at the Cambridge University Botanic Garden in 1992 [Changing Perspectives, 2014]

- 13. 13 Ruscus aculeatus This is the species familiar to horticulture and traditional usage in the British Isles. The stiff, spine-tipped cladodes resemble aristate leaves and bear attractive red berries in winter. Like all the other species in the genus, it exhibits a biennial growing behavior, with the stems flowering in the second year, then eventually dying down to the ground, as in some species of the closely related Smilax and Asparagus. R. aculeatus is native to Europe, North Africa and the Near East and grows in pine, beech and holm oak woods and scrub. It is, therefore, an indicator of Mediterranean habitats. It is widespread in southern England, becoming uncommon northward and ultimately absent in northern England and Scotland. It is, remarkably, the only monocotyledonous shrubby plant native to the British Isles [Bean, 1980]. Due to the wide distribution, there are a number of local individual forms [Yeo, 1968. Krüssmann, 1978]. Gertrude Jekyll described the derivation of the common English name butcher’s broom: “In country places where it abounds, butchers use the twigs tied in bunches to brush the little chips of meat off their great chopping-blocks, that are made of solid sections of elm trees, standing three and a half feet high and about two and a half feet across” [Jekyll, 1899]. The common Italian pungitopo and the German Mäusedorn signify “mouse-stinger” and are related with the old practice to put the well-armed branches around stored food to protect it from pests. Butcher’s broom has long been used in decorative arrangements and wreaths. Its prickly branches were also used by the producers of cigars in London for seasoning the tobacco leaves with saline liquor [Loudon, 1842]. The plant has a nutritional use, particularly in the Mediterranean countries, where the young shoots are eaten like asparagus spears [Pignatti, 1982] and seeds were once used to make a coffee-substitute [Hegi, 1939]. R. aculeatus. A Branches with male and female flowers and berries. B Apex of phylloclade. C Bract, bracteole and bud of female flower. D Pistil of female flower protruding from the stamina tube which has a rim formed by vestigial anthers. E Female flower in position on phylloclade. F Ovary, transverse section. G Seed. H Male flower in position on phylloclade. I Male flower, part of perianth cut away. J Staminal tube and anthers before dehiscence [Ross-Craig, 1972. Digitally modified picture]

- 14. 14 R. aculeatus is the most widely distributed and appreciated Ruscus species in British horticulture. However, once the compass needle moves south in latitude, the scenario becomes more intriguing and the genus reveals its true, charismatic colours. Important representatives are from the Mediterranean basin, comprising three taxa R. hypoglossum, R. hypophyllum and their probable hybrid R. x microglossus. The remaining three species are the Madeiran endemic R. streptophyllus, and R. colchicus and R. hyrcanus respectively from Caucasus and Azerbaijan. Distribution of the seven accepted taxa of Ruscus [Yeo, 1986. Digitally-modified picture] Ruscus hypophyllum This is readily distinguishable by its narrow cauline scale-leaves and the broad, pale green cladodes. The inflorescence-bracts are remarkably small, often papery. Stems can reach up to one meter, making it the taller taxon together with R. aculeatus. R. hypophyllum possibly presents the greater morphological variation within the genus. The inflorescences can be abaxial, adaxial, mixed, or occasionally even on both sides of the same cladode. In addition, the presumed constancy of monoecism is questionable [Yeo, 1968]. Its distribution ranges throughout the western Mediterranean Region, principally northern Africa as far East as Tunisia. Its introduction in the British Isles dates back to the beginning of the 18th , but there is disagreement on the exact date [Loudon, 1842. Bean, 1980]. It never found favour in cultivation, being more tender than R. aculeatus. The attractive, extremely rare R. hypophyllum f. crispatus is found in Morocco, featuring cladodes with undulate crispate margins.

- 15. 15 Ruscus hypoglossum This is a gentler version of R. aculeatus, presenting larger and softer cladodes. It is also the shorter-growing taxon within the genus, presenting branches up to half a meter tall. It is distinguished by its large foliaceous inflorescence-bracts, thus the common Italian name bislingua, meaning “double-tongue”, one tongue being the bract, the other the cladode. R. hypoglossum is found in Italy, Danube Region and Asiatic Turkey, typically in broad- leaved tree forests (especially beech), up to 1400 metres. It has been cultivated in England since the 16th Century [Bean, 1980], but is uncommon in gardens. It is totally hardy in the British Isles and does better than R. aculeatus in deep shade and when in competition with tree roots. Ruscus x microglossus This is a very attractive taxon presenting oblique, sometimes arching stems and metallic green cladodes that twist at the base. It can flower all year round [Walters et. al, 2011]. Only female plants are reported, possibly belonging to a single clone [Yeo, 1968]. R. x microglossus is thought to be a hybrid between R. hypoglossum and R. hypophylllum, resembling the former in foliage and overall habit, and the latter in smaller inflorescence bracts and in the generally abaxial flowers. Despite its ornamental value and botanic interest, R. x microglossus has often gone unrecognised. First described in 1857 by Antonio Bertoloni, one the most important Italian botanists of his time, this taxon has been largely neglected by taxonomists and often confused with the parental species, in particular R. hypophyllum. This is a rather surprising inaccuracy, especially considering that R. x microglossus is frequent in cultivation in Mediterranean gardens and occurs wild in woodlands throughout Italy and ex-Yugoslavian countries. It is not entirely clear how this hybrid has spread so widely and spontaneously in the wild. This could be the result of previous planting or – intriguingly – proof of R. x microglossus as a relict species. This hypothesis in part supported by the fact that the hybrid has proved to be at least partly fertile when pollinated with R. hypophyllum [Yeo, 1968]. Ruscus streptophyllus This is the most peripheral and rare species within the genus, endemic to Madeira, where grows in laurisilva, shady banks and rock ledges [Press et al., 2001]. Its oblique, arching stems reach 60 centimeters, with blackish-green cladodes horizontally arranged. It distinguishes itself by having resupinate cladodes, small bracts and constant adaxial inflorescence. It is also the only Ruscus species presenting constant monoecism. The width of the cladodes can vary considerably, so that two varieties latifolius (distichous cladodes) and lanceolatus (lower whorled cladodes) have been suggested. R. streptophyllus is the tenderest species within the genus and is still virtually unknown in cultivation. It can be grown under glass, flowering only in winter and early summer. It is also the only species having true leaves on the seedling, almost identical with those of Semele androgyna, a closely-related climber from the Canaries.

- 16. 16 Ruscus colchicus This is a half-hardy attractive species, with erect or oblique stems 60 centimeters tall. Its cladodes are distinctively pale green coloured and give the plants a gentle appearance. Morphological typifying features are the broad cauline scale-leaves and the constancy of the abaxial inflorescences. Flowers can also be either paired or solitary in the axil of the bract. R. colchicus is distributed in the eastern Black Sea Region, ranging from the coasts of north- east Turkey to the deciduous woodlands of the southern Caucasus up to 500 metres. It has long been confused with R. hypophyllum, although more closely allied with R. hypoglossum. Its taxonomic recognition is credited to Yeo, who procured plants from Georgia for the Cambridge University Botanic Garden, introducing the species into cultivation for the first time in the British Isles. He first started its cultivation under glass, but the plants proved to be hardy in the East Anglian climate and were moved outside. Ruscus hyrcanus This is the rare Azerbaijani endemic which replaces R. aculeatus, presenting branching stems and deep green, spine-tipped cladodes. It differs from its counterpart in the more dissected look of the cladodes, as well as the remarkably spreading and divaricate habit of the stems. R. hyrcanus is endemic to the Talish Mountains, where it grows naturally up to 1200 meters in the lowland forests with Parrotia persica and the closely related Danae racemosa. It can form dense thickets, impenetrable to walk through. It is endangered in the wild and protected in the Hirkan National Park, southeast Azerbaijan. R. aculeatus (left) and R. aculeatus var. platyphyllus (right) [Cambridge University Botanic Garden Herbarium, 2014]

- 17. 17 R. hypophyllum (top left), R. streptophyllus (top right), R. hyrcanus (bottom left) [Cambridge University Botanic Garden Herbarium, 2014] and R. hypophyllum f. crispatus (bottom right) [Global Plants, 2014]

- 18. 18 Ruscus in Contemporary British Horticulture In the British Isles the genus Ruscus and its differentiated taxa are rather neglected in cultivation. Only R. aculeatus, R. hypoglossum and few cultivars are commercially available, with 46 supplying nurseries [RHS Plant Finder, 2014]. Ruscus can be an unpopular choice in domestic gardens, but – significantly – more representation is found in the major botanical and horticultural institutions [BG-Base Users’ Collections, 2014]. Two National Collections also exist. One is held at the Cambridge University Botanic Garden, the other in the private garden of David Cann in Devon. This is the only complete collection of Ruscus in the British Isles and possibly in the world. REPRESENTATION OF RUSCUS IN BRITISH GARDENS, DEC 2014 Institution Taxa cultivated Notes Royal Botanic Gardens Kew (Richmond, London) R. aculeatus (24) R. aculeatus ‘Hermaphroditum’ (1) R. aculeatus ‘Lanceolatus’ (1) R. colchicus (3) R. hypoglossum (7) R. hyrcanus (1) R. streptophyllus (3) 45 accessions in the Living Collections database, distributed in the Arboretum, Display, Alpine and Herbaceous. Plants collected from the wild but also sourced from various nurseries Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh R. aculeatus R. aculeatus ‘Lanceolatus’ Severe climate proves to be a cultural barrier to the genus University of Oxford Botanic Garden (Oxfordshire) R. aculeatus R. colchicus R. colchicus was acquired from Royal Botanic Gardens Kew RHS Wisley (Surrey) R. aculeatus R. aculeatus var. angustifolius R. aculeatus ‘John Redmond’ R. aculeatus ‘Sparkler’ R. colchicus R. hypoglossum R. hypophyllum Four species cultivated and displayed, but also a good range of cultivars of R. aculeatus are grown and displayed for horticultural purposes. ‘John Redmond’ AGM is an extremely reliable selection Chelsea Physic Garden (London) R. aculeatus R. hypoglossum R. x microglossus R. hypophyllum used to be in the collection, but died a few years ago Sir Harold Hillier Gardens (Hampshire) R. aculeatus R. colchicus ‘Trabzon’ R. hypoglossum R. colchicus ‘Trabzon’ (raised by Roy Lancaster) is used effectively as groundcover Private garden of David Cann (Devon) R. aculeatus var. aculeatus (2) R. aculeatus var. angustifolius (1) R. aculeatus ‘John Redmond’ (1) R. aculeatus ‘Wheelers Variety’ (1) R. aculeatus ‘Lanceolatus’ (2) R. colchicus (3) R. hypoglossum (3) R. hypophyllum (2) R. hyrcanus (1) R. streptophyllus (2) R. x microglossus (1) 12 year old complete collection, with 11 cultivated taxa. Plants sourced from Kew, Edinburgh, Cambridge, several nurseries and private individuals. Plants are grown outside, except for R. hypophyllum (in the living room window sill) and R. streptophyllus (bathroom). Long narrow pots are used for propagation and contained plants, so accommodating the rhizomatous root system

- 19. 19 The overall impression is that the too-generically-named butcher’s brooms have never gained popularity in horticulture and still are judged as an indistinguishable ensemble of shrub-like plants, “quaint rather than pretty” [Lloyd, 1971]. In reality, Ruscus represents not only an interesting botanical oddity, but also a group of plants that can be highly useful and ornamental in modern horticulture. As garden plants, Ruscus are valued for their ability to live under the drip and shade of trees and in competition with greedy roots. In conditions where few evergreens could be cultivated, they will spread their rhizomes, giving rise to attractive cladodes and adding structure all year round. Ruscus shows a degree of adaptability and tenacity rarely equalled in other, more popular garden prima donnas. It is totally indifferent to soil type, proving to be cultivatable on chalk, acid sands and gravels; it can withstand salt gales and exposed conditions near the coast; it can tolerate long periods of drought; it is – moreover – trouble-free plants, disliked by most pests and diseases. Maintenance is minimal; coppicing or little thinning and division in March on a five-year basis will rejuvenate the plants. Opportunities are offered by the remarkable differentiation in qualitative as well quantitative characters within the genus. R aculeatus and R. hyrcanus are hardy and bear spine-tipped cladodes, which make them serviceable workhorses for car park or city planting, when discouragement is needed. They also have a short branched habit, which make them good material for florist decoration. R. hypoglossum and R. hypophyllum already have a commercial value in the Mediterranean countries as florist’s crops. The greater disadvantage in the garden environment lays in the insignificance of the inflorescences. However most of the species tend to flower on the upper side of the cladodes and will expose their attractive carmine berries. The hardiness can be a serious limitation, especially in northern counties. Furthermore, like many Mediterranean plants, Ruscus dislikes waterlogged soil, wet and damp winters and prolonged frost. Direct sunlight can also be a problem, where cladodes can get scorched. There is great variation in the sexuality of the flowers, as plants can be unisexual, bisexual or hermaphrodite. Unfortunately most species are dioecious, so male and female plants have to be planted in close proximity in order to achieve pollination and subsequent production of berries. However, hermaphrodite forms and cultivars exist. ‘Wheeler’s Variety’ and ‘Sparkler’ are valued for their free-fruiting habit. Rhizomatous root system of Ruscus hypophyllum. Picture by Giulio Veronese Ruscus hypophyllum is traditionally used in Sicilian gardens as a labour-saving edging plant. Picture by Giulio Veronese

- 20. 20 MORPHOLOGICAL VARIATION IN THE GENUS RUSCUS Taxa Stems Cladodes Flowers Hardiness R. aculeatus branched; erect; 70-100 cm spine tipped; numerous; ovate; twisted at the base; dark green adaxial; dioecious totally hardy; -15 to -20 °C min R. hypoglossum unbranched; oblique, at times arching above; 40 cm not-spine tipped; not petiolate; twisted at the base; obovate; thick; dark green adaxial; dioecious totally hardy; -15 to -20 °C min R. hypophyllum unbranched; erect; 70 cm (or to 1 m in the shade) not-spine tipped; petiolate; ovate; glossy; pale green variable position; monoecious (?) hardy in mild areas; -5 to -10 °C R. x microglossus unbranched; oblique, at times arching above; 50-60 cm not-spine tipped; petiolate; twisted at the base; obovate; dark green variable position; dioecious hardy in mild areas; -5 to -10 °C R. streptophyllus unbranched; oblique, arching distally; 60 cm not-spine tipped; twisted at the base; elliptic to ovate; blackish green adaxial; monoecious needs a cool glasshouse even in south Europe; 0 to -5 °C R. colchicus unbranched; erect or oblique, at times arching above; 60 cm not-spine tipped; petiolate; obovate to elliptic; glossy; pale green abaxial; dioecious hardy in mild areas; -5 to -10 °C R. hyrcanus branched; erect or oblique, divaricating distally; 30-50 cm spine tipped; elliptic or ovate; glossy; dark green adaxial; dioecious hardy in mild areas; -5 to -10 °C R. aculeatus R. aculeatus ‘Lanceolatus’ R. hypoglossum R. hypophyllum R. x microglossus R. streptophyllus R. colchicus R. hyrcanus Cladodes of different taxa of Ruscus. Pictures by Giulio Veronese except for R. aculeatus ‘Lanceolatus’, R. hypoglossum and R. hyrcanus by David Cann

- 21. 21 Representation and Cultivation in the Cambridge University Botanic Garden The Cambridge University Botanic Garden holds a National Collection of Ruscus. This is a living legacy of Dr. Peter Yeo, who was botanist, taxonomist and librarian at the Botanic Garden for 40 years. He developed the collection in the Sixties, thanks to contacts at Kew and Edinburgh Botanics, as well as in Russia, Georgia, France and Italy. Specimens of the original material are kept in the Garden Herbarium. The existing living collection is displayed in several different locations within the Garden, with most representatives planted in a perennial border along the West Walk, nearby the New Pinetum. Despite the displaying criteria being more ornamental than merely systematic, plants are often cultivated in combination with closely-related genera, such as Danae racemosa and Semele androgyna. At present the collection is incomplete, as R. hypoglossum and R. hyrcanus, once present, are now missing. COLLECTION OF RUSCUS IN THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY BOTANIC GARDEN, DEC 2014 Taxa no. Location, Condition and Cultivation Source R. aculeatus n Collection Display, entrance by Brookside Road, West Courtyard, Ostrya carpinifolia Bed, Woodland Garden, Mediterranean Garden, Systematic Beds, Ecological Mound and near messroom yard. Widely planted through the Garden as a foil plant, often in combination with Danae racemosa. Good companion could also be Sarcococca ruscifolia Wild collected but also Wisley Leningrad, Liege, Sarajevo, and Moppett (private individual) R. aculeatus var. angustifolius ? This was previously grown by the Magnolia Collection and under trees nearby the Fountain. According with BG-BASE the variety is no longer present in the Garden, but the original stock could still be under Arbutus unedo in the West Courtyard Chenault (private individual?) R. aculeatus dwarf form ? No record on BG-BASE on this taxon, but the specimens displayed in the Systematic Beds look remarkably shorter than any other in the Garden and could be R. aculeatus var. burgitensis Unknown R. colchicus 4 Collection Display and Brookside border; diverse conditions. Plants used to be grown in the Glasshouse Bay no.2 in Yeo’s time and then moved to the Caucasian Collection Batumi Botanical Garden (Georgia) R. hypophyllum 3 (+4) Collection Display and Bog Garden, plus potted stock in the polytunnel; fair conditions. Plants were originally grown in the Temperate Reserve Pit, then moved with R. hypoglossum to the Bog Garden. R. hypoglossum died there, presumably due to the moist conditions Jardin des Plantes, Montpellier and Major Johnston, France R. x microglossus ≈15 Collection Display, Ephedra Bed and at the back of the New Pinetum, underneath Thuja plicata. Very good conditions, especially under deep shade Miss Campbell, France R. streptophyllus 1 Glasshouse Range Corridor; good conditions. Specimen displayed alongside the closely related Semele androgyna Unknown

- 22. 22 Although the current system of displaying the collection according to its effective ornamental value is here acknowledged and appreciated, it is important to not disperse it. This would lead to more difficult management and recording, with taxa getting neglected and lost. Apart from the present main location on the West Walk, other good sites for collections could be the Ostrya carpinifolia bed along the Middle Walk or an island bed under the dry shade of the nearby birches. Greater visibility could also be given by displaying the plants in proximity of the public gates, such as under the big copper beech not far from Hills Road entrance or in the cycle park by Bateman Street entrance. A fascinating suggestion would be to locate the collection in the Glasshouse Courtyard, which will soon be re-landscaped and host mainly foliage plants. Several microclimates could be appositely created, so ensuring ideal growing conditions for virtually all the taxa apart from R. streptophyllus. An alternative solution of a permanent planting scheme is to grow the specimens in long narrow containers on a display bench. This system will ensure greater advantage in the maintaining, recording and displaying of the collection. It would be important to introduce the two missing species, reinstating a complete collection. R. hypoglossum grows naturally on the Continent and can be collected in the wild, while R. hyrcanus is more difficult to acquire, but material could come from Kew or the National Collection in Devon. It would also be interesting to get few of the several natural forms of R. aculeatus, as well as the real speciality R. hypophyllum f. crispatus. In terms of education, it is important to re-label the collection under Asparagaceae, in accordance with the currently accepted taxonomic system. Also an interpretation panel should be made, highlighting key facts on such a botanically-important genus. Past, present and possible future locations of the National Collection of Ruscus at CUBG

- 23. 23 A suggestion for an interpretation panel for the National Collection of Ruscus at CUBG Ruscaceae displayed in the Systematic Beds at CUBG

- 24. 24 Conclusion Ruscus is a charismatic group having strong botanical interest. The cladodes are the distinctive vegetative features and give unique character and appeal. Florally, the species present intriguing variation of monoecious and dioecious nature, inflorescence position and interspecific cross-fertility. Despite these attributes, Ruscus has always seemed to be somewhat overlooked, its scientific importance and horticultural potential having never fully been recognised. An interesting study could be on speciation. There are two obvious areas for such an investigation. Chromosome numbers are apparently unknown for the majority of the species, leaving open the question of polyploidy. The genus also presents an interesting biogeography, possibly related to post glacial history. Research on reproductive biology could also open the way to the possibility of interbreeding programmes. Self-pollination could be easily verified by growing genotypes in physical isolation. This could validate the theory that there are no barriers of sterility within the taxa [Yeo, 1968] and allow selections to be raised, which have desirable features for commercial value. The several forms of R. aculeatus could give hybrids of phenological and morphological interest. Ruscus has recognisable and distinctive characters, giving potential for becoming fashionable in horticulture. It represents a logical choice for botanic gardens, not just on the European Continent but also in countries with a dry to continental climate. It is also a fantastic choice for difficult horticultural situations, such as dry shade and heavy competition. Furthermore, the morphological connection with phyllocladous and sclerophyllous plants makes Ruscus worth testing in semi-arid or arid gardens, in the Northern as well as Southern Hemisphere, for example in combination with Opuntia, Colletia and Acacia. These considerations give scope in considering Ruscus a possible important plant for a changing climate, especially in terms of the future water shortage scenario. Ruscus aculeatus, Cyclamen hederifolium and Platycarya strobilacea at CUBG

- 25. 25

- 26. 26 References Bean, W.J. (1980). Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles. Vol. IV. 240-243. Bell, A. (1991). Plant Form. An Illustrated Guide to Flowering Plant Morphology. 126-127. Cubey, J. ed. (2014). The RHS Plant Finder 2014. 699. Dahlgren, R.M.T. et al. (1985). The Families of the Monocotyledons. 129-132. Gray, A. (1880). Structural Botany or Organography on the Basis of Morphology. 64-66. Grey-Wilson, C. et al. (1993). Mediterranean Wild Flowers. 484. Hegi, G. (1939). Illustrierte Flora von Mittel-Europa, ed. 2, 2. 334. Jekyll, G. (1899). Wood and Garden. Reprint - 1981. 209-210. Junker, K. (2007). Gardening with Woodland Plants. 314. Llyod, C. (1971). The Well-Tempered Garden. 190. Loudon, J.C. (1842). An Encyclopædia of Trees and Shrubs. 1100-1101. Krüssmann, G. (1978). Manual of Cultivated Broad-Leaved Trees & Shrubs. Vol. III. 271- 272. Pignatti, A. (1982). Flora d’Italia. Vol. III. 400-401. Phillips, R. et al. (1991). Perennials. Vol.2 Late Perennials. 226-227. Polunin, O. et al. (1990). Flowers of the Mediterranean. 218. Press, J.R. et al. (2001). Flora of Madeira. 390. Ross-Craig, S. (1972). Drawing of British Plants. Vol. XXIX. Table 10. Thomas, G.S. (1992). Ornamental Shrubs, Climbers and Bamboos. 362-363. Yeo, P.F. (1968). A Contribution to the Taxonomy of the Genus Ruscus. Notes from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Vol. XXVIII. 237-264. Walters et al. (2011). The European Garden Flora. Vol.1 Monocotyledonous. 168-170. Online sources The Angiosperm Phylogeny Website www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/APweb BG-Base Users’ Collections http://rbg-web2.rbge.org.uk/multisite/multisite3.php Changing Perspectives http://agardenthroughtime.com/themes/peter-yeo/ Global Plants http://plants.jstor.org/stable/history/10.5555/al.ap.specimen.bc825460 Liliod Monocot http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lilioid_monocot The Plant List. A Working List of all Plant Species http://www.theplantlist.org/tpl1.1/search?q=ruscus Tompkins County Flora Project http://tcf.bh.cornell.edu/imgs/dws/r/Alliaceae_Allium_caeruleum_15415.html

- 27. 27 Acknowledgements The preparation and writing of this essay has depended heavily on the support and inspiration of some great persons and friends. I am most grateful to Jenny Sargent for the use of the Cory Lodge Library; to Christine Bartram for the access to the material of CUBG Herbarium; to Pete Atkinson for the digital maps of CUBG and information on BG-BASE Users’ Collections; to Robert and Rannveig Wallis for suggesting some scientific references on the genus; to Mark Crouch and Ian Barker for indicating individual specimens cultivated at CUBG; to Helen Seal for inspiring ideas on how to display living collections; to Simon Wallis for some thought-provoking suggestions on the monocotyledons; to Peter Kerley for sharing with me his extensive knowledge on the National Collection of Ruscus at CUBG and its establishment; to Paul Aston for bravely proof-reading the first Italo-English draft of this essay; to Pete Michna for giving rise to further analysis and inspiration. Thanks also go to the colleagues that have passed me information from other major British gardens; to Rupert Harbinson at Kew; to Christopher Self at RHS Wisley; to Nell Jones at Chelsea Physic Garden. A warm thank goes to David Cann, holder of the National Collection of Ruscus in Devon, for his intelligent advice on specific botanical and horticultural questions on the genus; also for passing pictures of Ruscus species and taxa which are currently missing at CUBG. The beautiful photos of the plants and displays of Ruscus at CUBG were taken by Abramo De Licio on two frosty days of end autumn 2014. I am especially grateful to him for his always friendly support and professionalism. This work is dedicated to my father and the memory of a day of Ruscus propagated by subtraction.