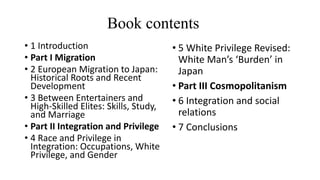

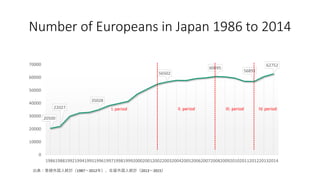

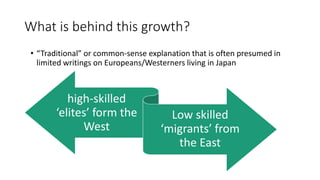

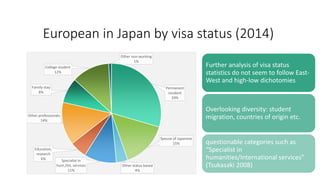

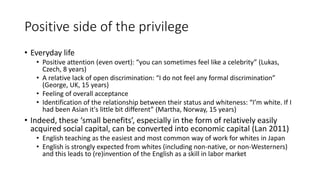

This document summarizes a book talk on a book about European migration to Japan. The book aims to deconstruct assumptions that such migrants are highly privileged cosmopolitans. It finds that factors behind European migration to Japan include lifestyle preferences and mobility culture rather than just high skills. While whiteness provides some social benefits, jobs are often precarious with low pay and security in English teaching or contingent academic work. Privilege is double-edged as other skills struggle to convert to opportunities due to racialized social roles. The book questions views of such migrants as problem-free elites.

![Are these niches privileged?

Working conditions and job insecurity:

• English teacher: myth of high income (shift since 1980s/90s): “Some of the stupidest things I’ve

ever heard …[is that] the foreigners come here to work as English teachers, make millions of

dollars and take it back home with them. English teachers earn about 2,500 dollars a month

[and t]hey can barely scrape through rent” (interviewee in Storlöpare’s (2013) documentary)

• Precarious jobs in high education: tenure track positions vs. fixed-terms (Anton) or part-time

lecturer (Vincenzo) positions are growing within the neo-liberal transformations of higher

education

• Many subjects working in highly deregulated non-regular forms of employment: these are in

Japan seen as highly unstable, with low social prestige, and not promising (Genda 2005), or

even as representing underclass (Sugimoto 2010:42)

• Relatively high share of self-employed (also from census data on UK nationals)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10-161025081449/85/Public-Lecture-Presentation-Slides-10-19-2016-Book-talk-Milos-Debnar-Europeans-in-Japan-Migration-and-Whiteness-17-320.jpg)