Recommended

PPTX

Chapter 11 1-3-Intermolecular Forces.pptx

PPT

PPT

PPT

PPTX

PPT

intermolecular_forces.ppt

PPT

intermolecular_forces.ppt

PPT

PPTX

2.-LESSON-2-INTERMOLECULAR-FORCE-OF-ATTRACTION.pptx

PPTX

Intermolecular and Intramolecular...pptx

PPTX

Intermolecular and Intramolecular...pptx

PPTX

Intermolecular Forces and Liquids and Solids.pptx

PPT

ap ch 11 intermolecular forces.ppt

PPT

intermolecular forces.ppt

PPT

ap ch 11 intermolecular forces.ppt

PPT

ap ch 11 intermolecular forces.ppt

PPT

PDF

Intermolecular forces module

PDF

Lecture 2-3. intermolecular forzes.pptx.pdf

PPT

Chapter 11 liquids and intermolecular forces Powerpoint

PDF

PHYSICAL-SCIENCE-Q3-Week-3_v2.pdf moreno

PPTX

Tang 09 intermolecular forces and solubility

PPT

Intermolecular_Forces_Liquids_and_Solids-Autosaved.ppt

PPTX

PPTX

PHYSICALSCIENCE Intermolecular-Forces.ppt.pptx

PPTX

Chapter 11 PowerPoint Lecture on Intermolecular Forces of Attraction.pptx

PDF

Interaction of Molecules in 3D Space: Determining Binding and Dissociation Co...

PPTX

Powerpoint for chapter 11.pptx

PPTX

Chapter3-power-points-Kotz1.pptx.........

PPT

CHEM12_C11_L3_LO (1).ppt.....................

More Related Content

PPTX

Chapter 11 1-3-Intermolecular Forces.pptx

PPT

PPT

PPT

PPTX

PPT

intermolecular_forces.ppt

PPT

intermolecular_forces.ppt

PPT

Similar to Zumdahl10e_PPT_Ch10.pptx.........................

PPTX

2.-LESSON-2-INTERMOLECULAR-FORCE-OF-ATTRACTION.pptx

PPTX

Intermolecular and Intramolecular...pptx

PPTX

Intermolecular and Intramolecular...pptx

PPTX

Intermolecular Forces and Liquids and Solids.pptx

PPT

ap ch 11 intermolecular forces.ppt

PPT

intermolecular forces.ppt

PPT

ap ch 11 intermolecular forces.ppt

PPT

ap ch 11 intermolecular forces.ppt

PPT

PDF

Intermolecular forces module

PDF

Lecture 2-3. intermolecular forzes.pptx.pdf

PPT

Chapter 11 liquids and intermolecular forces Powerpoint

PDF

PHYSICAL-SCIENCE-Q3-Week-3_v2.pdf moreno

PPTX

Tang 09 intermolecular forces and solubility

PPT

Intermolecular_Forces_Liquids_and_Solids-Autosaved.ppt

PPTX

PPTX

PHYSICALSCIENCE Intermolecular-Forces.ppt.pptx

PPTX

Chapter 11 PowerPoint Lecture on Intermolecular Forces of Attraction.pptx

PDF

Interaction of Molecules in 3D Space: Determining Binding and Dissociation Co...

PPTX

Powerpoint for chapter 11.pptx

More from KevWatts

PPTX

Chapter3-power-points-Kotz1.pptx.........

PPT

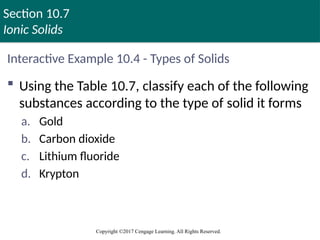

CHEM12_C11_L3_LO (1).ppt.....................

PPT

chapter_12_stoichiometry_-_powerpoint.ppt

PPTX

Atomic Structure Lesson Part 3.pptx.....

PPT

beerlambert-140929110335-phpapp02.ppt....

PPTX

Copy of Periodic Trends PowerPoint.pptx.

PPTX

Unit 3 lecture notes.pptx......................

PPTX

U6L6.pptx...............................

PPTX

U6L5.pptx.................................

PPT

gas_laws_part_1.ppt........................

PPTX

solutions.pptx............................

PPT

9221397.ppt..............................

PPT

Honors Chemistry ch 5.ppt/////////////////////

PPT

Honors Chemistry ch 5.ppt............................

PPTX

Section A3 - Bonding.pptx...................

PPT

iGCSE Chemistry Section 1 Lesson 1.ppt..

PPTX

U5L1P2.pptx......................................

PPTX

U5L1P1.pptx........................................

PPTX

Zumdahl10e_PPT_Ch11.pptx................

PPT

C8_U4_L4_TransitionMetalNomenclature.ppt

Recently uploaded

PPTX

Chapter 1: Introduction to Strategic Management.pptx

PDF

PPT Daftar Bahan Kelas Bedah Kitab Matius Khotbah di Bukit

PDF

Pratishta Educational Society., Courses & Opportunities

PPTX

GRADE 8 - QUARTER 4 TYPES AND PARTS OF LETTER.pptx

PPTX

A brief introduction to Minor vegetable crops.pptx

PPTX

Guidelines for reporting social networks and personal networks data

PDF

Types of Foot & Foot Modifications in Birds

PDF

How "Raiders of the Lost Ark" and "Ordinary People" Employ Non-Verbal Acting

PDF

PHARMACOLOGY 1 ( BP 404 T) Unit 1 (Cology 1)

PDF

Chapter 05 Drugs Acting on the Central Nervous System: Anti-Depressant Drugs

PDF

Tetracycline Class of Antibiotics: SAR, MOA and Uses

PDF

AI Is a Tool, Not a Voice: Radio, Trust, and the Human Factor

PDF

Orlando by Virginia Woolf: The Granite and The Rainbow

PPTX

Lesson_1 Acceleration.pptx_Science 8-4th quarter

PPTX

How to Track & Manage My Time Section in Odoo 18 Time Off

PDF

Judgement Regarding Land Acquisition Act not Applicable to Encroachers.pdf

PPTX

ENGLISH-7-Quarter-4-Week-3 Matatag .pptx

PDF

Chapter 05 Drugs Acting on the Central Nervous System: Anticonvulsant (Antiep...

PPTX

How to Track Employee Skill Growth with Skills Evolution Report in Odoo 18

PPTX

Math 8 Quarter 4 Week 4-SECONDARY DATA.pptx

Zumdahl10e_PPT_Ch10.pptx......................... 1. 2. Chapter 10

Table of Contents

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Table of Contents

(10.1) Intermolecular forces

(10.2) The liquid state

(10.3) An introduction to structures and types

of solids

(10.4) Structure and bonding in metals

(10.5) Carbon and silicon: Network atomic

solids

3. Chapter 10

Table of Contents

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Table of Contents Continued

(10.6) Molecular solids

(10.7) Ionic solids

(10.8) Vapor pressure and changes of state

(10.9) Phase diagrams

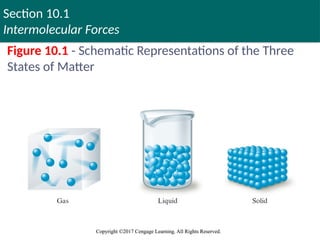

4. 5. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Intramolecular and Intermolecular Bonding

Intramolecular bonding - Occurs within molecules

Condensed states of matter - Liquids and solids

Forces involved

Covalent bonding

Ionic bonding

Intermolecular bonding: Occurs between molecules

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 5

6. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Changes in States

When a substance changes from solid to liquid to

gas, the molecules remain intact

Caused by the changes in the forces among the

molecules and not within the molecules

When energy is added to ice, the motion of the

molecules increases

Results in greater movement and disorder characteristic of

liquid water

7. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Changes in States (Continued)

When more energy is added to water, gaseous state is

eventually reached

Intermolecular distance increases, and intermolecular

interaction decreases

More energy is required to overcome the covalent

bonds and decompose the water molecules into their

component atoms

8. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Dipole–Dipole Forces

Forces that act between polar molecules

Dipole–dipole attraction: Electrostatic attraction

between molecules with dipole moments

Molecules orient themselves in a way that the positive

and negative ends are close to each other

In a condensed state, dipoles find the best

compromise between attraction and repulsion

9. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

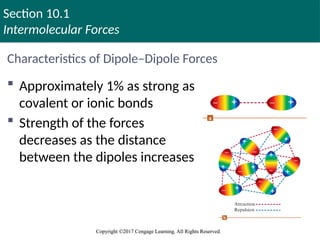

Characteristics of Dipole–Dipole Forces

Approximately 1% as strong as

covalent or ionic bonds

Strength of the forces

decreases as the distance

between the dipoles increases

10. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

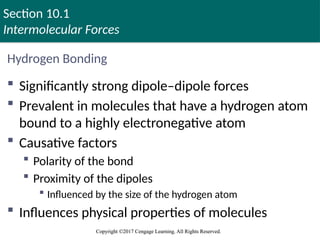

Hydrogen Bonding

Significantly strong dipole–dipole forces

Prevalent in molecules that have a hydrogen atom

bound to a highly electronegative atom

Causative factors

Polarity of the bond

Proximity of the dipoles

Influenced by the size of the hydrogen atom

Influences physical properties of molecules

11. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

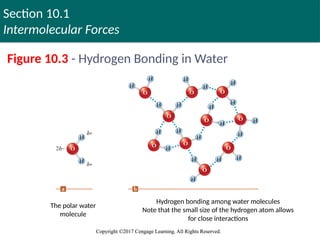

Figure 10.3 - Hydrogen Bonding in Water

The polar water

molecule

Hydrogen bonding among water molecules

Note that the small size of the hydrogen atom allows

for close interactions

12. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

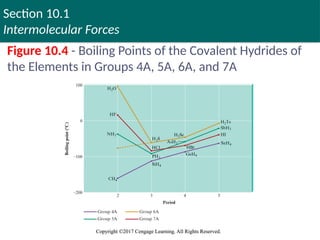

Figure 10.4 - Boiling Points of the Covalent Hydrides of

the Elements in Groups 4A, 5A, 6A, and 7A

13. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

London Dispersion Forces

Forces that exist among noble gas atoms and

nonpolar molecules

An accidental instantaneous dipole that occurs in

an atom can induce a similar dipole in a

neighboring atom

Leads to an interatomic attraction that is weak and

short-lived

Can be significant for large atoms

14. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

London Dispersion Forces (Continued)

Polarizability - Indicates the ease with which the

electron cloud of an atom can be distorted to give

a dipolar charge distribution

As the atomic number increases, the number of

electrons increases

Increases the probability of the occurrence of momentary

dipole interactions

Used by nonpolar molecules to attract each other

15. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Chemical and Physical Changes at the Macroscopic

Level

• Change in the form of the substance, but not in its

chemical composition

Physical change

• Change of substances into other substances with

different properties and different composition

Chemical change

16. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Distinguishing Chemical and Physical Changes

Aided by a molecular-level perspective

Example of a physical change

Phase change - Boiling of water

Energy as heat is transferred to liquid water

Intermolecular forces (hydrogen bonding) are overcome,

and water vapor is formed as a result

2 2

H O H O

l g

17. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Distinguishing Chemical and Physical Changes (continued)

Example of a chemical change

Combustion of methane (CH4) to form CO2 and H2O

Chemical bonds between C and H in CH4 and between O

atoms in O2 must be broken

Chemical bonds between C and O in CO2 and H and O in H2O

must be formed

4 2 2 2

CH + 2O CO + 2H O

18. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Dipole-Induced Dipole Interaction

Permanent dipole on a polar molecule induces a

dipole on a neighboring nonpolar molecule

Strength depends on the natures of both the polar

molecule and the nonpolar molecule

Larger the magnitude of the dipole in a polar

molecule, the better able it is to induce a dipole in a

neighboring molecule

19. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Dipole-Induced Dipole Interaction (continued)

Nonpolar molecules with a greater number of

electrons have an increased polarizability

Increases the ease with which a dipole is induced

20. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Critical Thinking

You have learned the difference between

intermolecular forces and intramolecular bonds

What if intermolecular forces were stronger than

intramolecular bonds?

What differences could you observe in the world?

21. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

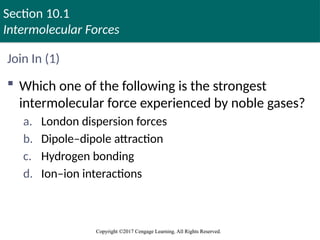

Join In (1)

Which one of the following is the strongest

intermolecular force experienced by noble gases?

a. London dispersion forces

b. Dipole–dipole attraction

c. Hydrogen bonding

d. Ion–ion interactions

22. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

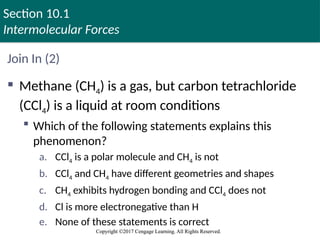

Join In (2)

Methane (CH4) is a gas, but carbon tetrachloride

(CCl4) is a liquid at room conditions

Which of the following statements explains this

phenomenon?

a. CCl4 is a polar molecule and CH4 is not

b. CCl4 and CH4 have different geometries and shapes

c. CH4 exhibits hydrogen bonding and CCl4 does not

d. Cl is more electronegative than H

e. None of these statements is correct

23. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

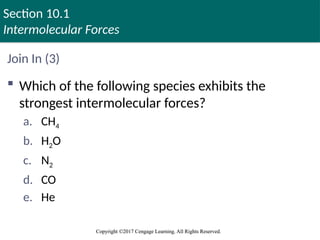

Join In (3)

Which of the following species exhibits the

strongest intermolecular forces?

a. CH4

b. H2O

c. N2

d. CO

e. He

24. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

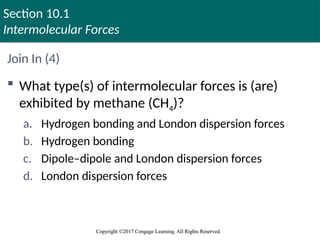

Join In (4)

What type(s) of intermolecular forces is (are)

exhibited by methane (CH4)?

a. Hydrogen bonding and London dispersion forces

b. Hydrogen bonding

c. Dipole–dipole and London dispersion forces

d. London dispersion forces

25. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

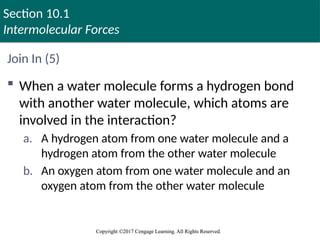

Join In (5)

When a water molecule forms a hydrogen bond

with another water molecule, which atoms are

involved in the interaction?

a. A hydrogen atom from one water molecule and a

hydrogen atom from the other water molecule

b. An oxygen atom from one water molecule and an

oxygen atom from the other water molecule

26. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

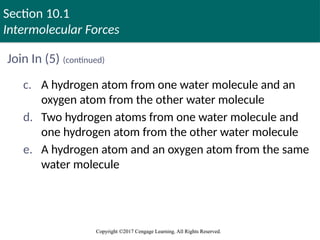

Join In (5) (continued)

c. A hydrogen atom from one water molecule and an

oxygen atom from the other water molecule

d. Two hydrogen atoms from one water molecule and

one hydrogen atom from the other water molecule

e. A hydrogen atom and an oxygen atom from the same

water molecule

27. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

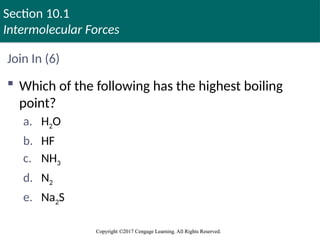

Join In (6)

Which of the following has the highest boiling

point?

a. H2O

b. HF

c. NH3

d. N2

e. Na2S

28. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

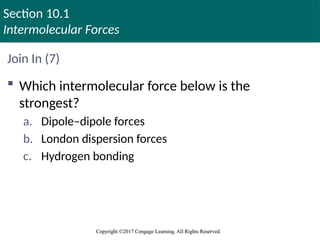

Join In (7)

Which intermolecular force below is the

strongest?

a. Dipole–dipole forces

b. London dispersion forces

c. Hydrogen bonding

29. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

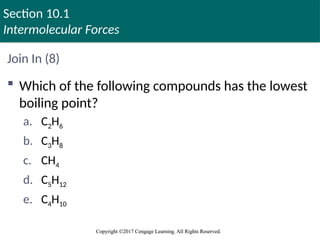

Join In (8)

Which of the following compounds has the lowest

boiling point?

a. C2H6

b. C3H8

c. CH4

d. C5H12

e. C4H10

30. Section 10.1

Intermolecular Forces

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

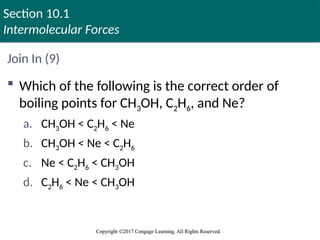

Join In (9)

Which of the following is the correct order of

boiling points for CH3OH, C2H6, and Ne?

a. CH3OH < C2H6 < Ne

b. CH3OH < Ne < C2H6

c. Ne < C2H6 < CH3OH

d. C2H6 < Ne < CH3OH

31. Section 10.2

The Liquid State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

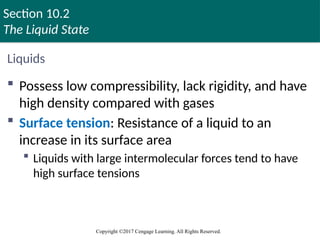

Liquids

Possess low compressibility, lack rigidity, and have

high density compared with gases

Surface tension: Resistance of a liquid to an

increase in its surface area

Liquids with large intermolecular forces tend to have

high surface tensions

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 31

32. Section 10.2

The Liquid State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

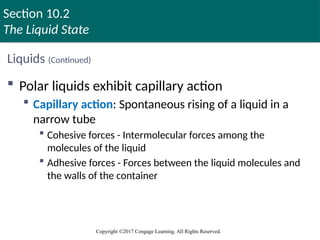

Liquids (Continued)

Polar liquids exhibit capillary action

Capillary action: Spontaneous rising of a liquid in a

narrow tube

Cohesive forces - Intermolecular forces among the

molecules of the liquid

Adhesive forces - Forces between the liquid molecules and

the walls of the container

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 32

33. Section 10.2

The Liquid State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

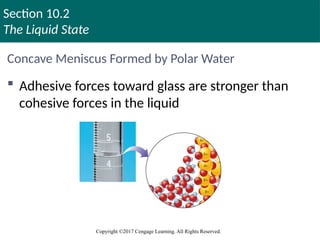

Concave Meniscus Formed by Polar Water

Adhesive forces toward glass are stronger than

cohesive forces in the liquid

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 33

34. Section 10.2

The Liquid State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

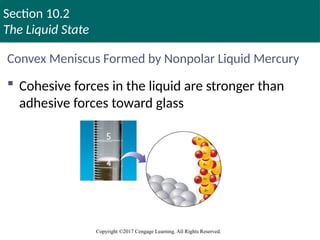

Convex Meniscus Formed by Nonpolar Liquid Mercury

Cohesive forces in the liquid are stronger than

adhesive forces toward glass

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 34

35. Section 10.2

The Liquid State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Viscosity

Measure of a liquid’s resistance to flow

Liquids with large intermolecular forces and

complex molecules tend to be highly viscous

Example - Glycerol and grease

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 35

36. Section 10.2

The Liquid State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Structural Model for Liquids

Have strong intermolecular forces and significant

molecular motions

Contain a large number of regions

Arrangement of the components are similar to those

that are present in solids, but with more disorder

Holes are present in a few regions

Regions are subject to rapid fluctuations

37. Section 10.2

The Liquid State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Join In (10)

Consider two liquids, A and B

Liquid A exhibits stronger intermolecular forces than

liquid B

Which of the following statements is true?

a. The surface tension and viscosity of liquid A are greater

than those of liquid B

b. The surface tension of liquid A is greater than that of liquid

B; the viscosity of liquid B is greater than that of liquid A

38. Section 10.2

The Liquid State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Join In (10) (continued)

c. The surface tension of liquid B is greater than that of liquid

A; the viscosity of liquid A is greater than that of liquid B

d. The surface tension and viscosity of liquid B are greater

than those of liquid A

39. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Classification of Solids

Amorphous solids: Have considerable disorder in

their structures

Crystalline solids: Characterized by highly regular

arrangement of components

Positions of components are represented by lattices

Lattice: Three-dimensional system of points designating

positions of components that make up the substance

Unit cell: Smallest repeating unit of a lattice

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 39

40. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

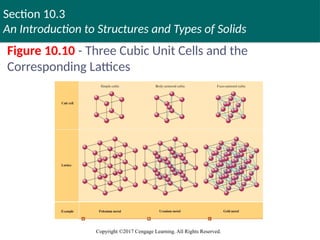

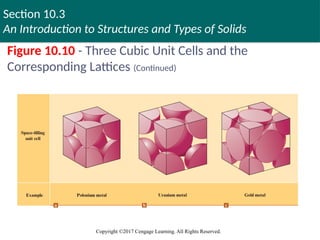

Figure 10.10 - Three Cubic Unit Cells and the

Corresponding Lattices

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 40

41. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Figure 10.10 - Three Cubic Unit Cells and the

Corresponding Lattices (Continued)

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 41

42. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

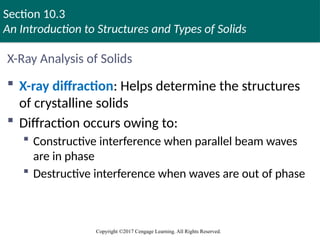

X-Ray Analysis of Solids

X-ray diffraction: Helps determine the structures

of crystalline solids

Diffraction occurs owing to:

Constructive interference when parallel beam waves

are in phase

Destructive interference when waves are out of phase

43. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

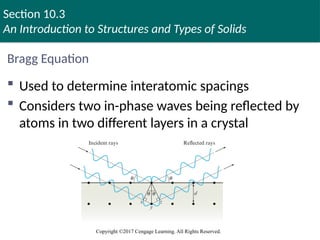

Bragg Equation

Used to determine interatomic spacings

Considers two in-phase waves being reflected by

atoms in two different layers in a crystal

44. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

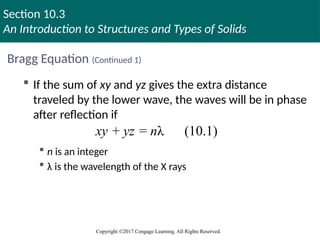

Bragg Equation (Continued 1)

If the sum of xy and yz gives the extra distance

traveled by the lower wave, the waves will be in phase

after reflection if

n is an integer

λ is the wavelength of the X rays

+ = λ (10.1)

xy yz n

45. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

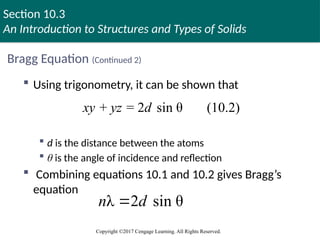

Bragg Equation (Continued 2)

Using trigonometry, it can be shown that

d is the distance between the atoms

θ is the angle of incidence and reflection

Combining equations 10.1 and 10.2 gives Bragg’s

equation

+ = 2 sin θ (10.2)

xy yz d

λ 2 sin θ

n d

46. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

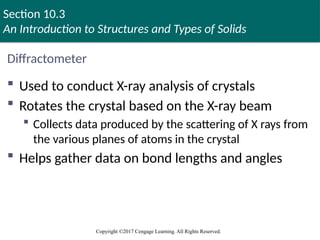

Diffractometer

Used to conduct X-ray analysis of crystals

Rotates the crystal based on the X-ray beam

Collects data produced by the scattering of X rays from

the various planes of atoms in the crystal

Helps gather data on bond lengths and angles

47. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

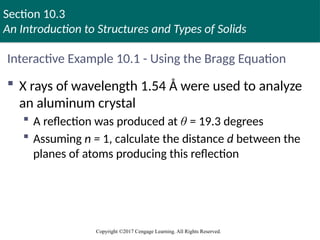

Interactive Example 10.1 - Using the Bragg Equation

X rays of wavelength 1.54 Å were used to analyze

an aluminum crystal

A reflection was produced at θ = 19.3 degrees

Assuming n = 1, calculate the distance d between the

planes of atoms producing this reflection

48. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

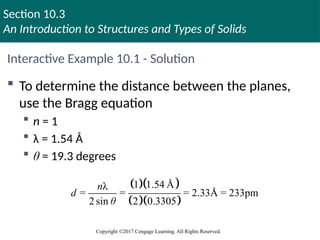

Interactive Example 10.1 - Solution

To determine the distance between the planes,

use the Bragg equation

n = 1

λ = 1.54 Å

θ = 19.3 degrees

1 1.54 Å

λ

= = = 2.33Å = 233pm

2 sin 2 0.3305

n

d

θ

49. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Types of Crystalline Solids

Ionic solids: Possess ions at the lattice points that

describe the structure of the solid

Molecular solids: Possess discrete covalently

bonded molecules at the lattice points

Atomic solids: Possess atoms at the lattice points

that describe the structure of the solid

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 49

50. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

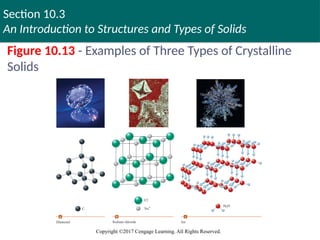

Figure 10.13 - Examples of Three Types of Crystalline

Solids

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 50

51. Section 10.3

An Introduction to Structures and Types of Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Classification of Atomic Solids

Metallic solids - Possess a special type of

delocalized nondirectional covalent bonds

Network solids - Possess atoms bonded by strong

directional covalent bonds

Bonds lead to giant molecules of atoms

Group 8A solids - Possess noble gas elements that

are attracted to each other by London dispersion

forces

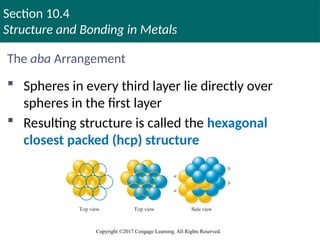

52. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Closest Packing Model

Closest packing arrangement

Characterized by layers of uniform hard spheres that

efficiently use available space

Each sphere is surrounded by six others

Types of arrangement

The aba arrangement

The abc arrangement

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 52

53. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

The aba Arrangement

Spheres in every third layer lie directly over

spheres in the first layer

Resulting structure is called the hexagonal

closest packed (hcp) structure

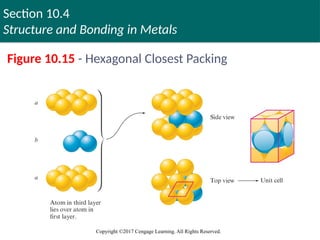

54. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Figure 10.15 - Hexagonal Closest Packing

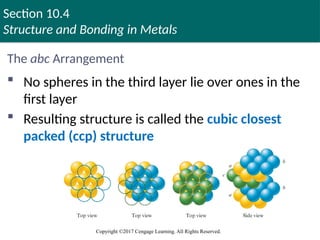

55. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

The abc Arrangement

No spheres in the third layer lie over ones in the

first layer

Resulting structure is called the cubic closest

packed (ccp) structure

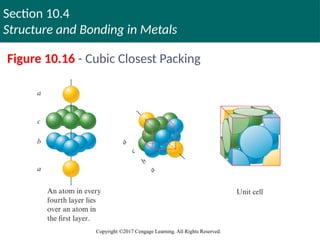

56. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Figure 10.16 - Cubic Closest Packing

57. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

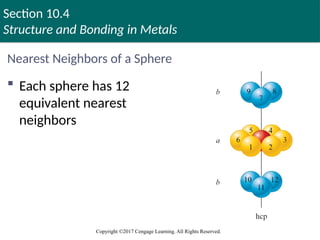

Nearest Neighbors of a Sphere

Each sphere has 12

equivalent nearest

neighbors

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 57

58. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

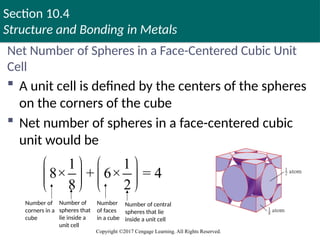

Net Number of Spheres in a Face-Centered Cubic Unit

Cell

A unit cell is defined by the centers of the spheres

on the corners of the cube

Net number of spheres in a face-centered cubic

unit would be

1 1

8× + 6× = 4

8 2

Number of

corners in a

cube

Number of

spheres that

lie inside a

unit cell

Number

of faces

in a cube

Number of central

spheres that lie

inside a unit cell

59. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Interactive Example 10.2 - Calculating the Density of a

Closest Packed Solid

Silver crystallizes in a cubic closest packed

structure

The radius of a silver atom is 144 pm

Calculate the density of solid silver

60. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Interactive Example 10.2 - Solution

Density is mass per unit volume

We need to know how many silver atoms occupy a

given volume in the crystal

The structure is cubic closest packed, which means the

unit cell is face-centered cubic

We must find the volume of this unit cell for silver and

the net number of atoms it contains

61. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

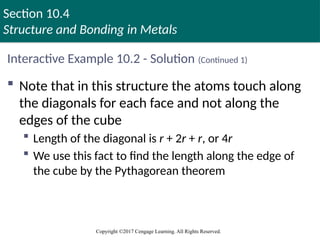

Interactive Example 10.2 - Solution (Continued 1)

Note that in this structure the atoms touch along

the diagonals for each face and not along the

edges of the cube

Length of the diagonal is r + 2r + r, or 4r

We use this fact to find the length along the edge of

the cube by the Pythagorean theorem

62. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

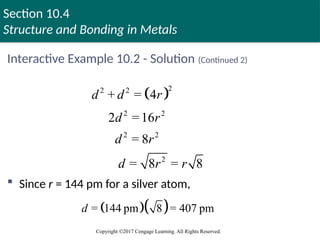

Interactive Example 10.2 - Solution (Continued 2)

2

2 2

2 2

2 2

2

+ = 4

2 =16

= 8

= 8 = 8

d d r

d r

d r

d r r

Since r = 144 pm for a silver atom,

= 144 pm 8 = 407 pm

d

63. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

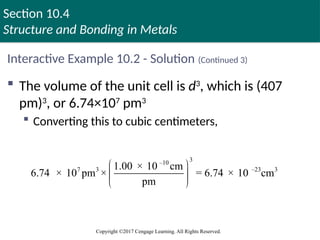

Interactive Example 10.2 - Solution (Continued 3)

The volume of the unit cell is d3

, which is (407

pm)3

, or 6.74×107

pm3

Converting this to cubic centimeters,

3

–10

7 3 –23 3

1.00 × 10 cm

6.74 × 10 pm × = 6.74 × 10 cm

pm

64. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

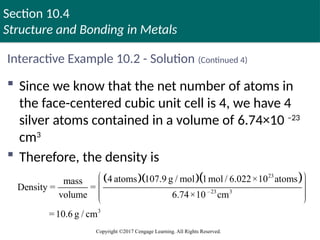

Interactive Example 10.2 - Solution (Continued 4)

Since we know that the net number of atoms in

the face-centered cubic unit cell is 4, we have 4

silver atoms contained in a volume of 6.74×10 –23

cm3

Therefore, the density is

23

–23 3

3

4 atoms 107.9 g / mol 1mol / 6.022×10 atoms

mass

Density = =

volume 6.74×10 cm

=10.6 g / cm

65. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Bonding Models for Metals

A successful bonding model for metals must

consider:

Malleability

Ductility

Efficient and uniform conduction of heat and

electricity

66. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Electron Sea Model

Envisions a regular array of metal cations in a sea

of valence electrons

Mobile electrons conduct heat and electricity

Metal ions freely move around as the metal is

hammered into a sheet or drawn into a wire

67. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

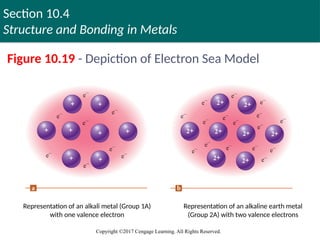

Figure 10.19 - Depiction of Electron Sea Model

Representation of an alkali metal (Group 1A)

with one valence electron

Representation of an alkaline earth metal

(Group 2A) with two valence electrons

68. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Band Model or Molecular Orbital (MO) Model

Electrons are assumed to travel around the metal

crystal in molecular orbitals formed from the

valence atomic orbitals of the metal atoms

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 68

69. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

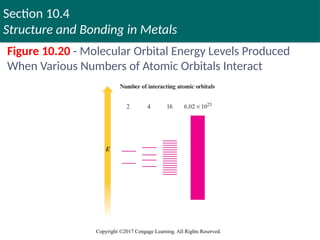

Figure 10.20 - Molecular Orbital Energy Levels Produced

When Various Numbers of Atomic Orbitals Interact

70. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

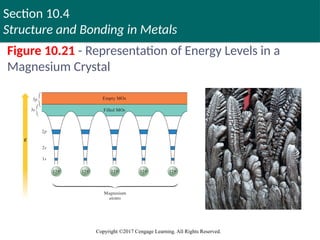

Figure 10.21 - Representation of Energy Levels in a

Magnesium Crystal

71. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

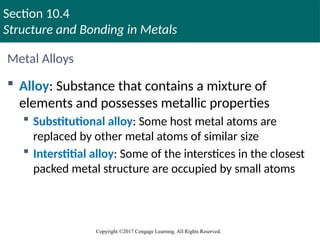

Metal Alloys

Alloy: Substance that contains a mixture of

elements and possesses metallic properties

Substitutional alloy: Some host metal atoms are

replaced by other metal atoms of similar size

Interstitial alloy: Some of the interstices in the closest

packed metal structure are occupied by small atoms

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 71

72. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

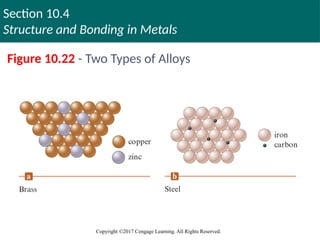

Figure 10.22 - Two Types of Alloys

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 72

73. Section 10.4

Structure and Bonding in Metals

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

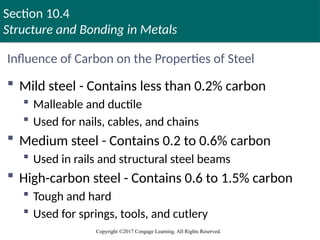

Influence of Carbon on the Properties of Steel

Mild steel - Contains less than 0.2% carbon

Malleable and ductile

Used for nails, cables, and chains

Medium steel - Contains 0.2 to 0.6% carbon

Used in rails and structural steel beams

High-carbon steel - Contains 0.6 to 1.5% carbon

Tough and hard

Used for springs, tools, and cutlery

74. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Network Solids

Atomic solids that contain directional covalent

bonds

Form solids that are viewed as giant molecules

Properties

Brittle in nature

Ineffective conductors of heat and electricity

75. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

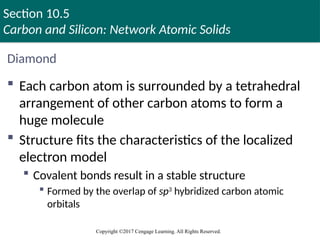

Diamond

Each carbon atom is surrounded by a tetrahedral

arrangement of other carbon atoms to form a

huge molecule

Structure fits the characteristics of the localized

electron model

Covalent bonds result in a stable structure

Formed by the overlap of sp3

hybridized carbon atomic

orbitals

76. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

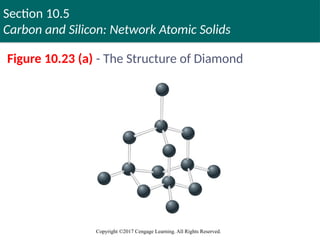

Figure 10.23 (a) - The Structure of Diamond

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 76

77. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Diamond (Continued)

Structure according to the MO model

A large gap between the filled and empty levels exists

Electron transfer is difficult

Diamond is not expected to be a good electrical conductor

Used in industrial cutting implements

Graphite can be converted to diamond by applying

150,000 atm of pressure at 2800°C

78. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

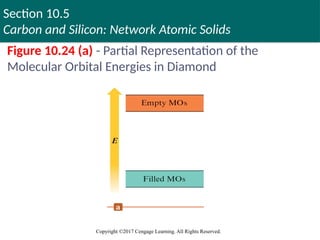

Figure 10.24 (a) - Partial Representation of the

Molecular Orbital Energies in Diamond

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 78

79. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

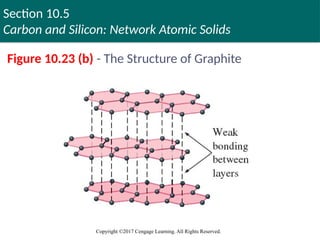

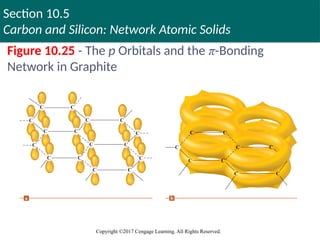

Graphite

Slippery, black, and a conductor of heat and

electricity

Structure is based on layers of carbon atoms

arranged in fused six-membered rings

Each carbon atom in a layer is surrounded by three

other carbon atoms in a trigonal planar arrangement

with 120-degree bond angles

80. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Graphite (Continued)

sp2

hybridization is predicted by the localized

electron model

Three sp2

orbitals on each carbon atom form σ bonds

with three other carbon atoms

One 2p orbital on each carbon remains unhybridized

and is perpendicular to the plane

Used as a lubricant in locks

Slipperiness is due to the strong bonding within the

layers of carbon atoms rather than between the layers

81. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Figure 10.23 (b) - The Structure of Graphite

82. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Figure 10.25 - The p Orbitals and the π-Bonding

Network in Graphite

83. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

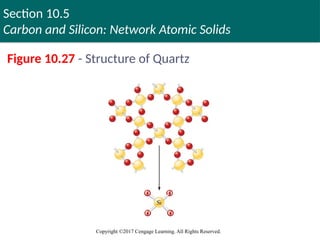

Silicon

An important constituent of the compounds that

form the earth’s crust

Stable silicon compounds involve chains with

silicon–oxygen bonds

Silica (SiO2): Fundamental silicon–oxygen compound

Structure

Silicon atom satisfies the octet rule by forming single

bonds with four oxygen atoms

84. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Figure 10.27 - Structure of Quartz

85. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Silicates

Compounds related to silica

Based on interconnected SiO4 tetrahedra

Found in rocks, soils, and clays

Possess O/Si ratios greater than 2:1 and contain

silicon–oxygen anions

Cations are required to balance the excess negative

charge to form neutral silicates

86. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Silicates (Continued)

Glass: Amorphous solid that is formed when silica

is heated above 1600°C and cooled rapidly

Homogeneous, noncrystalline frozen solution

Common glass results when substances, such as

Na2CO3, are added to the silica melt and then cooled

Properties vary based on the additives

87. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

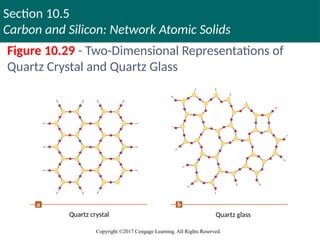

Figure 10.29 - Two-Dimensional Representations of

Quartz Crystal and Quartz Glass

Quartz crystal Quartz glass

88. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

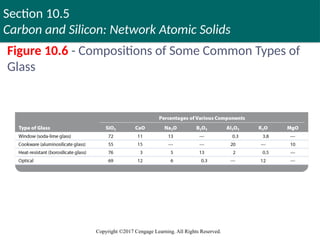

Figure 10.6 - Compositions of Some Common Types of

Glass

89. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Ceramics

Made from clays and hardened by firing at high

temperatures

Nonmetallic materials that are strong, brittle, and

resistant to heat and attack by chemicals

Heterogeneous in nature

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 89

90. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Structure of Clay

Formed by the weathering action of water and

carbon dioxide on the mineral feldspar

Feldspar - An aluminosilicate that weathers to form

kaolinite

Kaolinite - Consists of tiny thin platelets with the empirical

formula Al2Si2O5(OH)4

Platelets interlock as the clay dries

During firing, silicates and cations form a glass that

binds the crystals of kaolinite

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 90

91. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Uses of Ceramics

Construction of jet and automobile engines

Flexible ceramics can be obtained by adding small

amounts of organic polymers

Organic polymers are used to produce durable engine

parts, flexible superconducting wires and

microelectronic devices, and prosthetic devices

92. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Semiconductors

Conduct only a slight electric current at room

temperature

Show increased conductivity at higher temperatures

Types

n-type semiconductor

Substance whose conductivity is increased by doping the

element with atoms that have more valence electrons than

the atoms in the host crystal

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 92

93. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Semiconductors (Continued)

p-type semiconductor: Semiconductors are doped

with atoms that have fewer valence electrons than the

atoms in the host crystal

Substance becomes a better conductor

A p-type and an n-type semiconductor can be

connected to form a p–n junction

Makes an excellent rectifier

Rectifier - Device that produces a pulsating direct current

from alternating current

94. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

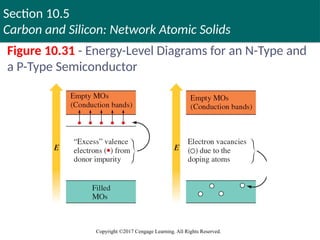

Figure 10.31 - Energy-Level Diagrams for an N-Type and

a P-Type Semiconductor

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 94

95. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

P–N Junction

A small number of electrons migrate from the n-

type region into the p-type region

The migrations place a negative charge on the p-type

region and a positive charge on the n-type region

Contact potential prevents further migration

Contact potential - Charge buildup

96. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

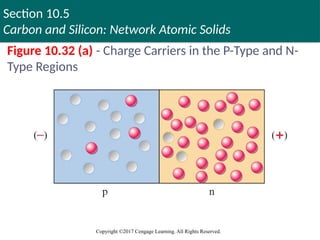

Figure 10.32 (a) - Charge Carriers in the P-Type and N-

Type Regions

97. Section 10.5

Carbon and Silicon: Network Atomic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

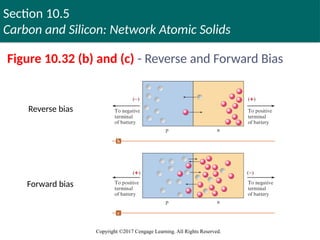

Figure 10.32 (b) and (c) - Reverse and Forward Bias

Reverse bias

Forward bias

98. Section 10.6

Molecular Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Molecular Solids

Characterized by strong covalent bonding within

molecules and weak bonding between molecules

Intermolecular forces depend on the nature of the

molecules

Molecules that do not have a dipole moment possess

London dispersion forces

Molecules with dipole moments have greater

intermolecular forces when hydrogen bonding is

possible

99. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Ionic Solids

Stable, high-melting substances held together by

the strong electrostatic forces that exist between

oppositely charged ions

Structure of binary ionic solids can be explained

by closest packing of spheres

Spheres are packed to:

Maximize electrostatic attractions among oppositely charged

ions

Minimize repulsions among ions with like charges

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 99

100. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

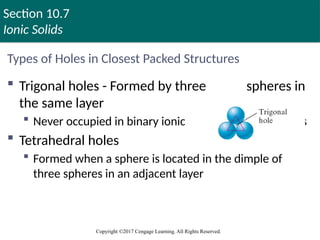

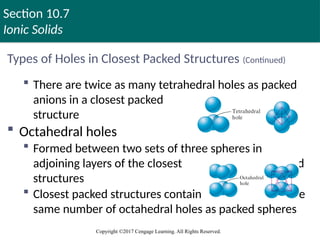

Types of Holes in Closest Packed Structures

Trigonal holes - Formed by three spheres in

the same layer

Never occupied in binary ionic compounds

Tetrahedral holes

Formed when a sphere is located in the dimple of

three spheres in an adjacent layer

101. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Types of Holes in Closest Packed Structures (Continued)

There are twice as many tetrahedral holes as packed

anions in a closest packed

structure

Octahedral holes

Formed between two sets of three spheres in

adjoining layers of the closest packed

structures

Closest packed structures contain the

same number of octahedral holes as packed spheres

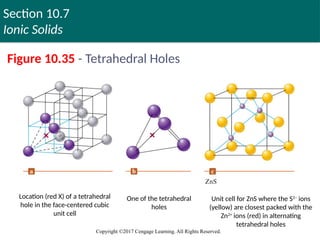

102. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Figure 10.35 - Tetrahedral Holes

Location (red X) of a tetrahedral

hole in the face-centered cubic

unit cell

One of the tetrahedral

holes

Unit cell for ZnS where the S2–

ions

(yellow) are closest packed with the

Zn2+

ions (red) in alternating

tetrahedral holes

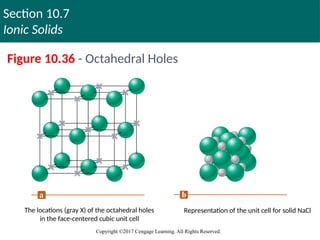

103. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Figure 10.36 - Octahedral Holes

The locations (gray X) of the octahedral holes

in the face-centered cubic unit cell

Representation of the unit cell for solid NaCl

104. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Interactive Example 10.3 - Determining the Number of

Ions in a Unit Cell

Determine the net number of Na+

and Cl–

ions in

the sodium chloride unit cell

105. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

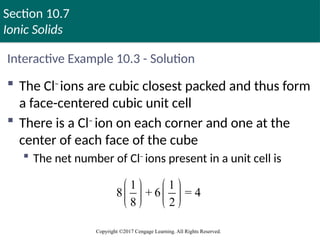

Interactive Example 10.3 - Solution

The Cl–

ions are cubic closest packed and thus form

a face-centered cubic unit cell

There is a Cl–

ion on each corner and one at the

center of each face of the cube

The net number of Cl–

ions present in a unit cell is

1 1

8 + 6 = 4

8 2

106. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Interactive Example 10.3 - Solution (Continued 1)

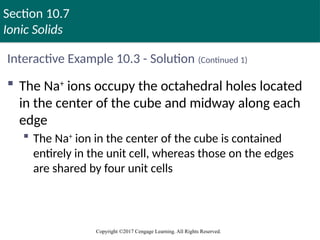

The Na+

ions occupy the octahedral holes located

in the center of the cube and midway along each

edge

The Na+

ion in the center of the cube is contained

entirely in the unit cell, whereas those on the edges

are shared by four unit cells

107. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Interactive Example 10.3 - Solution (Continued 2)

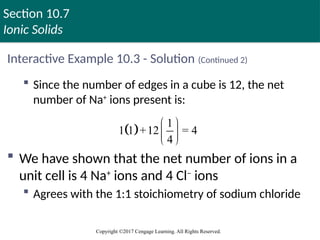

Since the number of edges in a cube is 12, the net

number of Na+

ions present is:

We have shown that the net number of ions in a

unit cell is 4 Na+

ions and 4 Cl–

ions

Agrees with the 1:1 stoichiometry of sodium chloride

1

1 1 +12 = 4

4

108. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

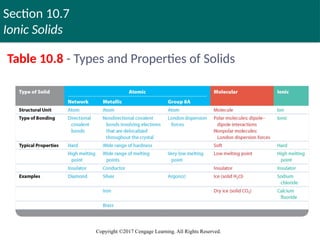

Table 10.8 - Types and Properties of Solids

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 108

109. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Interactive Example 10.4 - Types of Solids

Using the Table 10.7, classify each of the following

substances according to the type of solid it forms

a. Gold

b. Carbon dioxide

c. Lithium fluoride

d. Krypton

110. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

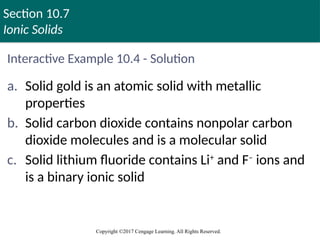

Interactive Example 10.4 - Solution

a. Solid gold is an atomic solid with metallic

properties

b. Solid carbon dioxide contains nonpolar carbon

dioxide molecules and is a molecular solid

c. Solid lithium fluoride contains Li+

and F–

ions and

is a binary ionic solid

111. Section 10.7

Ionic Solids

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

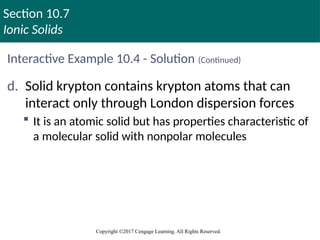

Interactive Example 10.4 - Solution (Continued)

d. Solid krypton contains krypton atoms that can

interact only through London dispersion forces

It is an atomic solid but has properties characteristic of

a molecular solid with nonpolar molecules

112. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

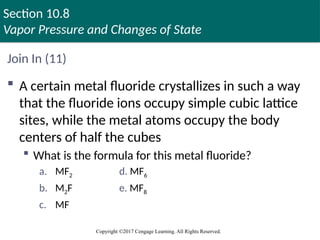

Join In (11)

A certain metal fluoride crystallizes in such a way

that the fluoride ions occupy simple cubic lattice

sites, while the metal atoms occupy the body

centers of half the cubes

What is the formula for this metal fluoride?

a. MF2 d. MF6

b. M2F e. MF8

c. MF

113. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Join In (12)

Which of the following statements is incorrect?

a. Ionic solids generally have high melting points

b. Ionic solids are insulators

c. The binding forces in a molecular solid include

London dispersion forces

d. Molecular solids generally have high melting points

114. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Join In (13)

A certain metal fluoride crystallizes in such a way

that the fluoride ions occupy simple cubic lattice

sites, while the metal ions occupy the body

centers of half the cubes

Which of the following could be the metal ion?

a. The calcium ion d. The vanadium(IV) ion

b. The sodium ion e. Any of these ions

c. The iron(III) ion

115. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Vaporization (Evaporation)

Molecules of a liquid escape the liquid’s surface to

form a gas

Heat of vaporization (ΔHvap ): Energy required to

vaporize 1 mole of a liquid at a pressure of 1 atm

Endothermic in nature

116. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

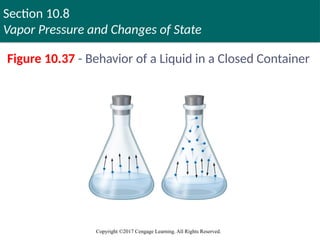

Figure 10.37 - Behavior of a Liquid in a Closed Container

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 116

117. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Vapor Pressure

Equilibrium: The point at which no further net

change occurs in the amount of liquid or vapor

Rate of condensation equals rate of evaporation

Condensation: Process by which gases become liquids

Equilibrium vapor pressure: Pressure of vapor at

equilibrium

118. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

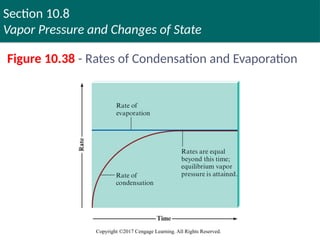

Figure 10.38 - Rates of Condensation and Evaporation

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 118

119. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

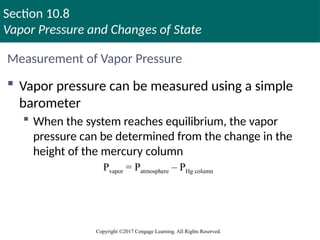

Measurement of Vapor Pressure

Vapor pressure can be measured using a simple

barometer

When the system reaches equilibrium, the vapor

pressure can be determined from the change in the

height of the mercury column

Pvapor = Patmosphere – PHg column

120. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

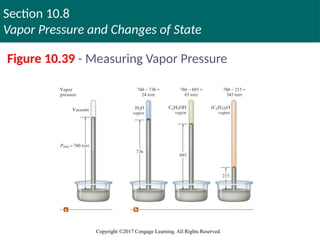

Figure 10.39 - Measuring Vapor Pressure

121. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Critical Thinking

You have seen that the water molecule has a bent

shape and therefore is a polar molecule

This accounts for many of water’s interesting

properties

What if the water molecule was linear?

How would this affect the properties of water, such as its

surface tension, heat of vaporization, and vapor pressure?

How would life be different?

122. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Vapor Pressure and Liquids

Liquids with high vapor pressures are volatile

Evaporation occurs rapidly in an open environment

The size of the intermolecular forces in a liquid

determines its vapor pressure

Substances with large molar masses have relatively

low vapor pressures

123. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Vapor Pressure and Liquids (Continued)

Vapor pressure increases significantly with

temperature

A molecule must have sufficient kinetic energy to

overcome intermolecular forces

124. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

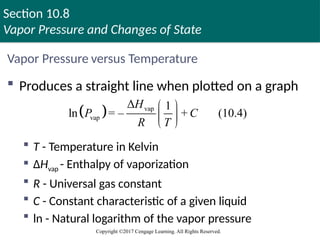

Vapor Pressure versus Temperature

Produces a straight line when plotted on a graph

T - Temperature in Kelvin

ΔHvap - Enthalpy of vaporization

R - Universal gas constant

C - Constant characteristic of a given liquid

ln - Natural logarithm of the vapor pressure

vap

vap

Δ 1

ln = – + (10.4)

H

P C

R T

125. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

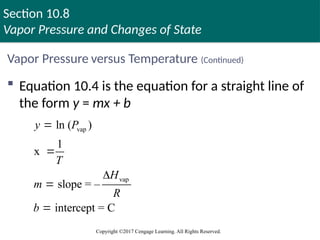

Vapor Pressure versus Temperature (Continued)

Equation 10.4 is the equation for a straight line of

the form y = mx + b

vap

vap

ln ( )

1

x

slope = –

intercept = C

y P

T

H

m

R

b

126. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

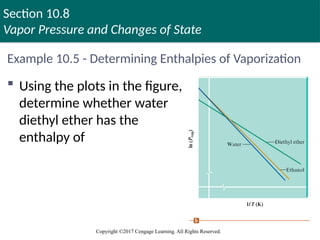

Example 10.5 - Determining Enthalpies of Vaporization

Using the plots in the figure,

determine whether water or

diethyl ether has the larger

enthalpy of vaporization

127. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

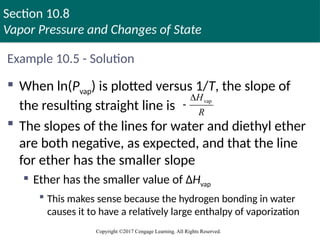

Example 10.5 - Solution

When ln(Pvap) is plotted versus 1/T, the slope of

the resulting straight line is

The slopes of the lines for water and diethyl ether

are both negative, as expected, and that the line

for ether has the smaller slope

Ether has the smaller value of ΔHvap

This makes sense because the hydrogen bonding in water

causes it to have a relatively large enthalpy of vaporization

vap

H

R

128. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

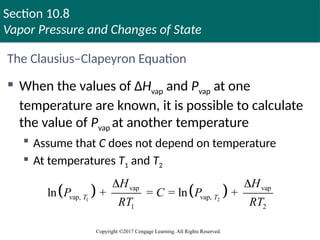

The Clausius–Clapeyron Equation

When the values of ΔHvap and Pvap at one

temperature are known, it is possible to calculate

the value of Pvap at another temperature

Assume that C does not depend on temperature

At temperatures T1 and T2

1 2

vap vap

vap, vap,

1 2

ln + = = ln +

T T

H H

P C P

RT RT

129. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

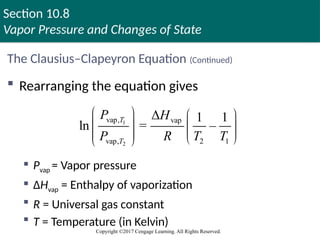

The Clausius–Clapeyron Equation (Continued)

Rearranging the equation gives

Pvap = Vapor pressure

ΔHvap = Enthalpy of vaporization

R = Universal gas constant

T = Temperature (in Kelvin)

1

2

vap, vap

vap, 2 1

Δ 1 1

ln = –

T

T

P H

P R T T

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 129

130. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

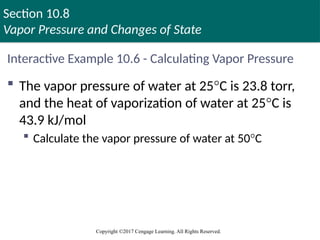

Interactive Example 10.6 - Calculating Vapor Pressure

The vapor pressure of water at 25°C is 23.8 torr,

and the heat of vaporization of water at 25°C is

43.9 kJ/mol

Calculate the vapor pressure of water at 50°C

131. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

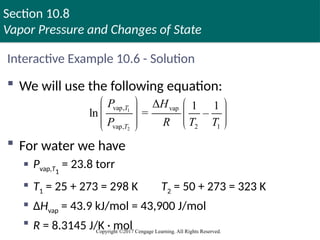

Interactive Example 10.6 - Solution

We will use the following equation:

For water we have

Pvap,T1

= 23.8 torr

T1 = 25 + 273 = 298 K T2 = 50 + 273 = 323 K

ΔHvap = 43.9 kJ/mol = 43,900 J/mol

R = 8.3145 J/K · mol

1

2

vap, vap

vap, 2 1

Δ 1 1

ln = –

T

T

P H

P R T T

132. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

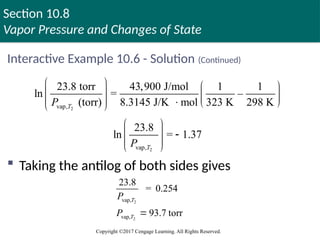

Interactive Example 10.6 - Solution (Continued)

Taking the antilog of both sides gives

2

vap,

23.8 torr 43,900 J/mol 1 1

ln = –

(torr) 8.3145 J/K mol 323 K 298 K

T

P

2

vap,

23.8

ln = 1.37

T

P

2

2

vap,

vap,

23.8

= 0.254

93.7 torr

T

T

P

P

133. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Sublimation

Process in which solids change to gases without

passing through the liquid state

Occurs with dry ice and iodine

134. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Changes of State

Heating curve: Plot of temperature versus time

for a process where energy is added at a constant

rate

When a solid is heated, it melts to form a liquid

If the heating continues, it will eventually form the vapor

phase

Heat of fusion (enthalpy of fusion): Change in

enthalpy at the melting point of a solid

135. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

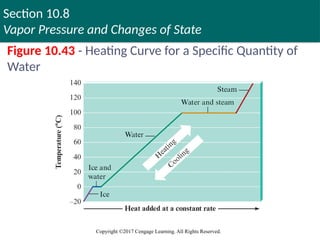

Figure 10.43 - Heating Curve for a Specific Quantity of

Water

136. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

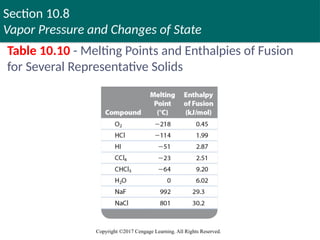

Table 10.10 - Melting Points and Enthalpies of Fusion

for Several Representative Solids

137. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

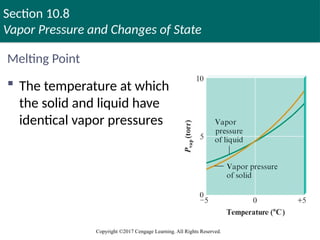

Melting Point

The temperature at which

the solid and liquid have

identical vapor pressures

138. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

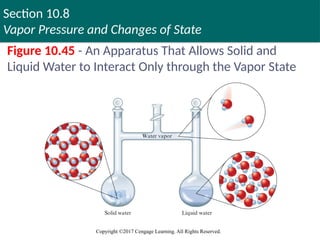

Figure 10.45 - An Apparatus That Allows Solid and

Liquid Water to Interact Only through the Vapor State

139. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Temperature and Vapor Pressure - Case 1

Temperature at which the vapor pressure of the

solid is greater than that of the liquid

The solid releases vapor, attempting to achieve

equilibrium

The liquid attempts to achieve equilibrium by

absorbing vapor

Net effect - Conversion from solid to liquid through the

vapor phase

Temperature would be above the melting point of ice

140. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Temperature and Vapor Pressure - Case 2

Temperature at which vapor pressure of the solid

is less than that of the liquid

Liquid will disappear, and the amount of ice will

increase

Solid will achieve equilibrium with the vapor

Temperature should be below the melting point of ice

141. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

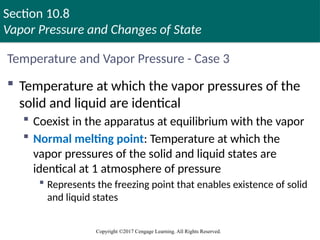

Temperature and Vapor Pressure - Case 3

Temperature at which the vapor pressures of the

solid and liquid are identical

Coexist in the apparatus at equilibrium with the vapor

Normal melting point: Temperature at which the

vapor pressures of the solid and liquid states are

identical at 1 atmosphere of pressure

Represents the freezing point that enables existence of solid

and liquid states

142. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Temperature and Vapor Pressure - Case 3 (Continued 1)

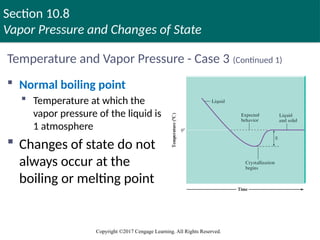

Normal boiling point

Temperature at which the

vapor pressure of the liquid is

1 atmosphere

Changes of state do not

always occur at the

boiling or melting point

143. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

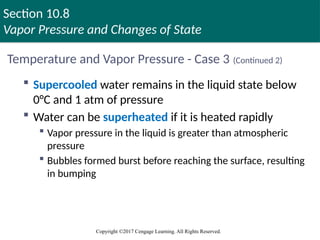

Temperature and Vapor Pressure - Case 3 (Continued 2)

Supercooled water remains in the liquid state below

0°C and 1 atm of pressure

Water can be superheated if it is heated rapidly

Vapor pressure in the liquid is greater than atmospheric

pressure

Bubbles formed burst before reaching the surface, resulting

in bumping

144. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

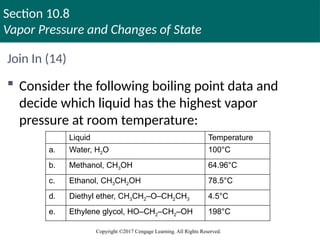

Join In (14)

Consider the following boiling point data and

decide which liquid has the highest vapor

pressure at room temperature:

Liquid Temperature

a. Water, H2O 100°C

b. Methanol, CH3OH 64.96°C

c. Ethanol, CH3CH2OH 78.5°C

d. Diethyl ether, CH3CH2–O–CH2CH3 4.5°C

e. Ethylene glycol, HO–CH2–CH2–OH 198°C

145. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

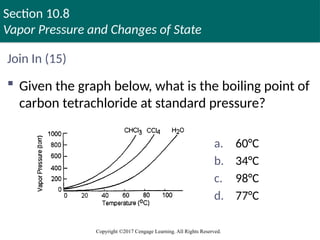

Join In (15)

Given the graph below, what is the boiling point of

carbon tetrachloride at standard pressure?

a. 60°C

b. 34°C

c. 98°C

d. 77°C

146. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

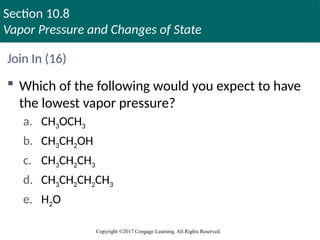

Join In (16)

Which of the following would you expect to have

the lowest vapor pressure?

a. CH3OCH3

b. CH3CH2OH

c. CH3CH2CH3

d. CH3CH2CH2CH3

e. H2O

147. Section 10.8

Vapor Pressure and Changes of State

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Join In (17)

What is the vapor pressure of water at 70°C?

a. 5.00 atm

b. 1.20 atm

c. 1.00 atm

d. 0.31 atm

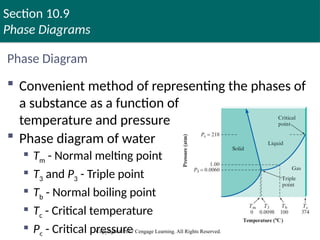

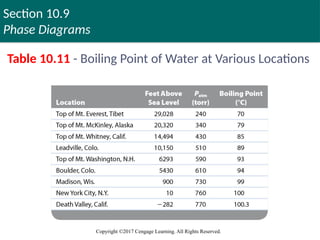

148. Section 10.9

Phase Diagrams

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Phase Diagram

Convenient method of representing the phases of

a substance as a function of

temperature and pressure

Phase diagram of water

Tm - Normal melting point

T3 and P3 - Triple point

Tb - Normal boiling point

Tc - Critical temperature

Pc - Critical pressure

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 148

149. Section 10.9

Phase Diagrams

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Phase Diagram (Continued)

Triple point: Temperature at which all three

phases exist simultaneously

Critical point: Defined by critical pressure and

temperature

Critical pressure: Pressure required to produce

liquefaction at the critical temperature

Critical temperature: The temperature above which

vapor cannot be liquefied, irrespective of the

pressure applied

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved 149

150. Section 10.9

Phase Diagrams

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

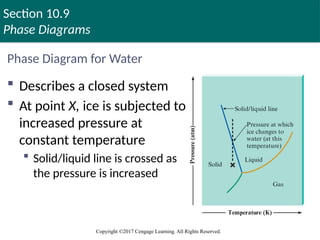

Phase Diagram for Water

Describes a closed system

At point X, ice is subjected to

increased pressure at

constant temperature

Solid/liquid line is crossed as

the pressure is increased

151. Section 10.9

Phase Diagrams

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Phase Diagram for Water - Observations

The solid/liquid boundary line has a negative

slope

At the melting point, liquid and solid are in

dynamic equilibrium

When pressure is applied, the volume is reduced

A given mass of ice has more volume at 0°C than the

same mass of water in liquid state

Freezing point of water is less than 0°C when external

pressure is greater than 1 atm

152. Section 10.9

Phase Diagrams

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Phase Diagram for Water - Applications

Ice skating

Narrow blades of skates exert a large amount of

pressure

Frictional heat caused when skates moves over ice

contributes to further melting of ice

As the blades pass by, the liquid refreezes

Low density of ice

Causes ice formed on rivers and lakes to float and this

helps prevent water bodies from freezing in the winter

153. 154. Section 10.9

Phase Diagrams

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Critical Thinking

Ice is less dense than liquid water, as evidenced by

the fact that ice floats in a glass of water

What if ice was more dense than liquid water?

How would this affect the phase diagram for water?

155. Section 10.9

Phase Diagrams

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

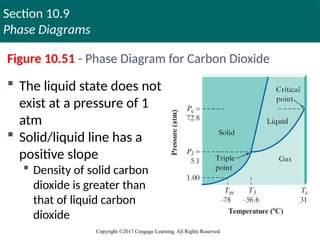

Figure 10.51 - Phase Diagram for Carbon Dioxide

The liquid state does not

exist at a pressure of 1

atm

Solid/liquid line has a

positive slope

Density of solid carbon

dioxide is greater than

that of liquid carbon

dioxide

156. Section 10.9

Phase Diagrams

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

Phase Diagram for Carbon Dioxide - Applications

Carbon dioxide is used in fire extinguishers

Liquid released from the extinguisher into the

environment at 1 atm immediately changes to a vapor

Dry ice

A convenient refrigerant as it does not undergo the

liquid phase under normal atmospheric conditions

157. Section 10.9

Phase Diagrams

Copyright ©2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.

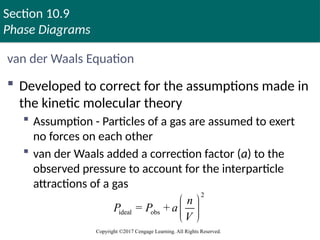

van der Waals Equation

Developed to correct for the assumptions made in

the kinetic molecular theory

Assumption - Particles of a gas are assumed to exert

no forces on each other

van der Waals added a correction factor (a) to the

observed pressure to account for the interparticle

attractions of a gas

2

ideal obs

= +

n

P P a

V

158. Editor's Notes #21 Correct answer

London dispersion forces

Noble gases are nonpolar, so their only intermolecular forces are London dispersion forces

#22 Correct answer

None of these statements is correct

Both molecules are nonpolar (both are tetrahedral)

Since CCl4 has more electrons than CH4, its London forces are stronger; so CCl4 is a liquid, while CH4 is a gas

#23 Correct answer

H2O

Water exhibits hydrogen bonding

Methane (CH4), N2, and He exhibit London dispersion forces

Carbon monoxide (CO) exhibits dipole–dipole attraction

#24 Correct answer

London dispersion forces

Methane is a nonpolar molecule (it has a tetrahedral geometry and shape), so it exhibits London dispersion forces

#26 Correct answer

A hydrogen atom from one water molecule and an oxygen atom from the other water molecule

The hydrogen–oxygen chemical bond is quite polar, leaving the hydrogen with a partial positive charge and the oxygen with a partial negative charge

Thus the hydrogen from one water molecule has an attraction to the oxygen of the other water molecule

#27 Correct answer

Na2S

The highest boiling point should result from an ionic compound with ion–ion forces of attraction

The only ionic compound in these choices is Na2S

#28 Correct answer

Hydrogen bonding

Hydrogen bonds are the strongest owing to the great polarity of the bond and the close approach of the dipoles

#29 Correct answer

CH4

The lowest boiling point should result from the species with the weakest intermolecular forces

Of the species given here, CH4 has the weakest London dispersion forces and is the smallest in size

#30 Correct answer

Ne < C2H6 < CH3OH

The boiling points are determined by size and intermolecular forces

Ne has the lowest boiling point because it is the smallest and has only London dispersion forces

C2H6 is next; it has only London dispersion forces

CH3OH is next; it has hydrogen bonding

#38 Correct answer

The surface tension and viscosity of liquid A are greater than those of liquid B

As the strength of intermolecular forces increases, both surface tension (a measure of a liquid’s resistance to an increase in its surface area) and viscosity (a measure of a liquid’s resistance to flow) generally increase

#112 Correct answer

MF2

Since the fluoride ions occupy simple cubic lattice sites and the metal (M) ions occupy half of the body-centered sites, the formula would be M½F or MF2

#113 Correct answer

Molecular solids generally have high melting points

Molecular solids exhibit London dispersion forces, which indicate that they have low melting points

Ionic solids exhibit ionic forces, which indicate that they have high melting points and have the ability to be insulators

If the ionic compounds are molten, they are conductors

#114 Correct answer

The calcium ion

Each unit cell contains one F– ion

Because the metal ions are in half the unit cells, the metal ion must have a 2+ charge

The only choice with a 2+ charge is the calcium ion

#144 Correct answer

Diethyl ether, CH3CH2–O–CH2CH3

The substance with the lowest boiling point should have the highest vapor pressure at room temperature

#145 Correct answer

77°C

According to the graph, at 760 torr vapor pressure the temperature of CCl4 is 77°C, which is its boiling point

#146 Correct answer

H2O

Water exhibits hydrogen bonding, as does ethanol (choice b)

However, there are two hydrogen atoms on water that can hydrogen-bond to other water molecules

Because the intermolecular forces exhibited by water are greater than the intermolecular forces for the other choices, its vapor pressure would be the lowest

#147 Correct answer

0.31 atm

The normal boiling point of water (i.e., the temperature at which water boils at 1 atm) is 100°C, so the vapor pressure of water at 100°C is 1 atm

Because vapor pressure increases with increasing temperature, the vapor pressure at 70°C must be less than 1 atm

Only one choice (0.31 atm) is less than 1 atm