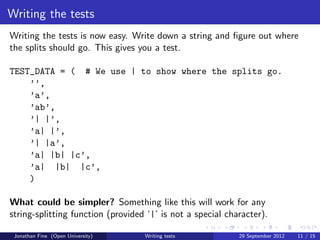

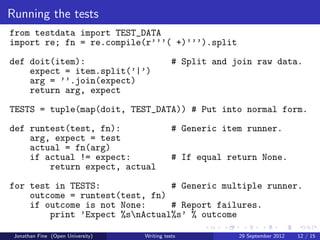

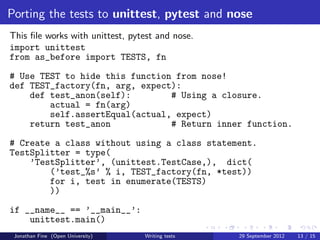

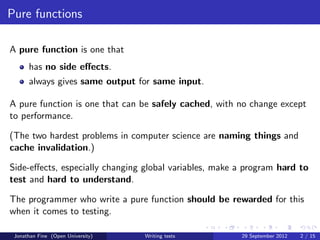

The document discusses writing tests for a function that splits a string into pieces based on repeated whitespace. It describes issues with existing testing frameworks like unittest, pytest and nose being verbose. It then proposes a better way to write tests by specifying the expected output pieces separated by a character like '|' and joining them to get the input string. This allows easily specifying multiple test cases as a string and mapping them to the split function. It shows how to implement the tests across different frameworks like unittest, pytest and nose while keeping the test data portable.

![Example: Split a string into pieces

Suppose we’re writing a wiki language parser, a syntax highlighter, or

something similar. We’ll have to split the input string(s) into pieces.

Writing the parser is not our present problem.

Our problem here is to write the tests for the function that splits

the string into pieces.

For simplicity, we assume that we want to split the string on repeated

white space. We can write such a splitter using a regular expression.

>>> import re

>>> fn = re.compile(r’’’( +)’’’).split

>>> fn(’this and that ’)

[’this’, ’ ’, ’and’, ’ ’, ’that’, ’ ’]

In fact, our task now is to make it easier to write tests for fn (which

in reality will be much more complicated than the above).

Jonathan Fine (Open University) Writing tests 29 September 2012 3 / 15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2012-writing-tests-slides-120928143626-phpapp02/85/Writing-tests-3-320.jpg)

![Writing tests with doctest

Python’s interactive console is very useful for exploring and learning. The

doctest module, part of Python’s standard library, allows console

sessions to be used as tests. Here’s some examples.

>>> import re; fn = re.compile(r’’’( +)’’’).split

>>>

>>> fn(’a b c’) # As we’d expect.

[’a’, ’ ’, ’b’, ’ ’, ’c’]

>>>

>>> fn(’atb c’) # Tabs not counted as white space.

[’atb’, ’ ’, ’c’]

>>>

>>> fn(’ ’) # Is this what we want?

[’’, ’ ’, ’’]

Good for examples, but what if we have 20 input-output pairs to test?

Jonathan Fine (Open University) Writing tests 29 September 2012 4 / 15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2012-writing-tests-slides-120928143626-phpapp02/85/Writing-tests-4-320.jpg)

![Writing tests with unittest

The unittest module, part of the standard library, is modelled on Java

and Smalltalk testing frameworks. It’s a bit verbose.

import fn # The function we want to test.

class TestSplitter(unittest.TestCase): # Container.

def test_1(self):

arg = ’a b c’

expect = [’a’, ’ ’, ’b’, ’ ’, ’c’]

actual = fn(arg) # Boilerplate.

self.assertEqual(actual, expect) # Boilerplate.

Problems: (1) It’s verbose (but why?). (2) Every test is a function.

(3) arg and expect are not parameters to the test. (4) Nor is fn.

(5) We have to give every test a name (even if we don’t want to).

(6) We can’t easily loop over (arg, expect) pairs.

Jonathan Fine (Open University) Writing tests 29 September 2012 5 / 15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2012-writing-tests-slides-120928143626-phpapp02/85/Writing-tests-5-320.jpg)

![Writing tests with pytest

The pytest package was developed to meet the needs of the PyPy project.

Around 2010 there was a major cleanup refactoring. It’s available on PyPI.

import fn # The function we want to test.

def test_1():

arg = ’a b c’

expect = [’a’, ’ ’, ’b’, ’ ’, ’c’]

actual = fn(arg) # Boilerplate.

assert actual == expect # Boilerplate.

Problems: (1) It’s less but still verbose . (2) Every test is a function.

(3) arg and expect are not parameters to the test. (4) Nor is fn.

(5) We have to give every test a name (even if we don’t want to).

(6) We’re not looping over (arg, expect) pairs.

(7) (Not shown): it used to use magic for error reporting.

(8) (Not shown): it now uses rewrite of assert for this.

Jonathan Fine (Open University) Writing tests 29 September 2012 6 / 15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2012-writing-tests-slides-120928143626-phpapp02/85/Writing-tests-6-320.jpg)

![Writing tests with nose

The nose package seems to be a rewrite of pytest to meet magic (and

other?) concerns. It’s available on PyPI. Many tests will work for both

packages. Our example (and most of the problems) are the same as before.

import fn # The function we want to test.

def test_1():

arg = ’a b c’

expect = [’a’, ’ ’, ’b’, ’ ’, ’c’]

actual = fn(arg) # Boilerplate.

assert actual == expect # Boilerplate.

Problems: (1) It’s less but still verbose . (2) Every test is a function.

(3) arg and expect are not parameters to the test. (4) Nor is fn.

(5) We have to give every test a name (even if we don’t want to).

(6) We’re not looping over (arg, expect) pairs.

(7) (Not shown): it has opaque error reporting.

Jonathan Fine (Open University) Writing tests 29 September 2012 7 / 15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2012-writing-tests-slides-120928143626-phpapp02/85/Writing-tests-7-320.jpg)

![Splitting a string into pieces has a special property

Enough of the assert stuff! It’s a distraction. Our problem is to write

tests for a function that splits a string into pieces. In our example

(below) no pieces are lost.

>>> import re; fn = re.compile(r’’’( +)’’’).split

>>> fn(’a b c’) # As we’d expect.

[’a’, ’ ’, ’b’, ’ ’, ’c’]

The input string is the join of the output (below). So all we have to

do is specify the output (and join it to get the input).

>>> arg = ’a b c’

>>> actual = fn(arg)

>>> ’’.join(actual) == arg

True

Let’s use this special property to help write our tests!

Jonathan Fine (Open University) Writing tests 29 September 2012 9 / 15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2012-writing-tests-slides-120928143626-phpapp02/85/Writing-tests-9-320.jpg)

![Creating a sequence of strings from test data

Recall that to write a test all we have to do is specify the ouput. We

can get the input as the join of the output.

Q: What’s an easy way to specify a sequence of strings?

A: How about splitting on a character?

>>> import re; fn = re.compile(r’’’( +)’’’).split

>>>

>>> test_data = ’’’a| |b| |c’’’

>>> expect = test_data.split(’|’)

>>> arg = ’’.join(expect)

>>> arg

’a b c’

>>> expect

[’a’, ’ ’, ’b’, ’ ’, ’c’]

>>> fn(arg) == expect

True

Jonathan Fine (Open University) Writing tests 29 September 2012 10 / 15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2012-writing-tests-slides-120928143626-phpapp02/85/Writing-tests-10-320.jpg)