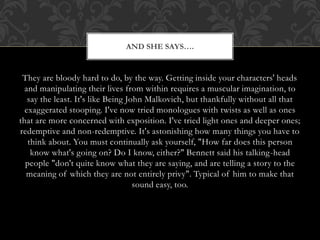

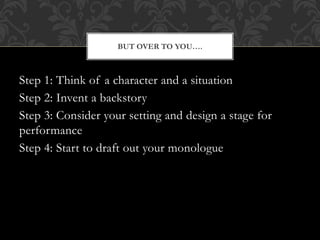

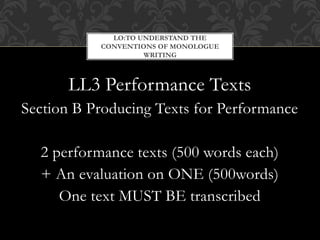

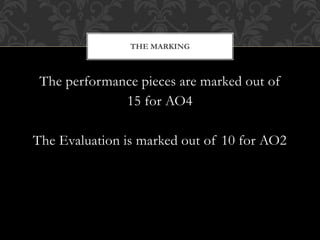

This document provides guidance on writing monologues for performance assessments. It discusses conventions of monologues, including providing context and stage directions. It emphasizes choosing distinct topics and including features like fillers and pauses for "spontaneous" pieces. Examples of successful monologues from works by McPherson, Bennett, and Newhart are referenced, and comments discuss the challenges of inhabiting a character's perspective and manipulating their life through monologue. Students are guided to consider a character, backstory, setting, and draft their own monologue.

![The thing about monologue is that it's immediate. It happens now. It happens

here. And it is literally "im-mediate", in that there is ostensibly no mediation:

nothing intervening between the character and the audience. That's why, in certain

magical theatrical circumstances, it can seem to fill the world. Everyone can think

of a moment in a great play when attention zooms in on a single character telling

a story - and the audience simply stops breathing. It happened memorably in

Conor McPherson's The Weir, for example, as each of the characters told their

tale; and it's a famous reward at the end of Eugene O'Neill's The Iceman Cometh.

In Pinter's The Caretaker, with its pivotal speech from Aston about electro-

convulsive therapy, it provides one of the best moments of western theatre: "He

showed me a pile of papers, and he said that I'd got something, some complaint.

He said ... he just said that, you see. You've got ... this thing. That's your

complaint. And we've decided, he said, that in your interests there's only one

course we can take [...] he said, we're going to do something to your brain."

COMMENTS BY LYNNE TRUSS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/writingmonologues-140607135050-phpapp02/85/Writing-monologues-11-320.jpg)