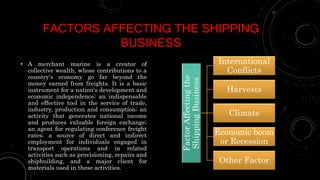

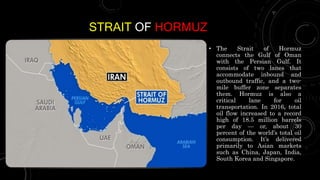

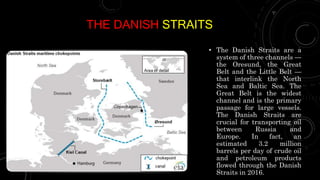

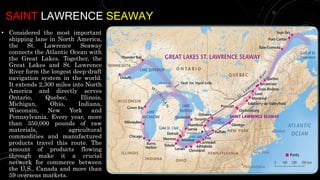

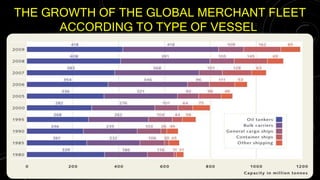

The document analyzes the evolution of maritime transport and its role in globalization, finding that income growth, rather than the maritime transport revolution, primarily fueled the late 19th-century global trade boom. It outlines significant trends in seaborne trade over the past 50 years, highlighting the dominance of shipping in international trade, especially in developing countries, and detailing key shipping routes and their economic significance. Additionally, it discusses various factors affecting the shipping business and the growth of the global merchant fleet.