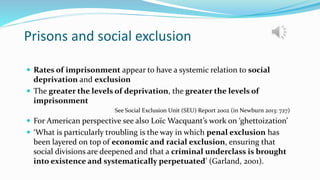

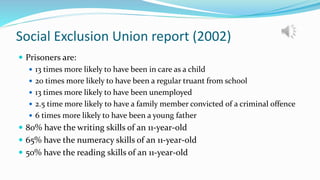

This document provides an overview of the history and development of prisons and imprisonment. It discusses how prisons emerged from institutions designed to contain the poor in the 16th century. Major reformers in the 18th-19th centuries advocated for more humane treatment of prisoners. The 19th century saw the rise of the penitentiary system with solitary confinement intended for prisoner reform. Overcrowding, human rights issues, and the social costs of mass imprisonment are ongoing concerns today.

![Prison Reform in the UK

1779: Penitentiary Act - reform through work and penance

1816: Millbank, first National Penitentiary in the UK

Shift toward segregation and isolation of prisoners – total

institutions

1. ‘Separate system’: isolation all day every day

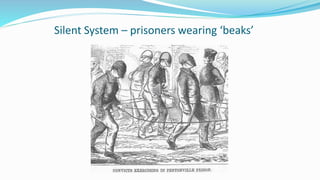

2. ‘Silent system’: isolation at night; silent association with others

during day

‘Day after day, with no companion but his thoughts, the convict is compelled to

listen to the reproofs of conscience. He is led to dwell upon past errors, and to

cherish whatever better feelings he may at any time have imbibed. [...] The mind

becomes open to the best impressions and prepared for the reception of those

truths and consolations which Christianity can alone impart.’ (Crawford, in Smith,

2004: 206)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week8prisonsandimprisonmentbb2-230107125839-bd0ede56/85/Week-8-Prisons-and-Imprisonment-BB-2-pptx-8-320.jpg)