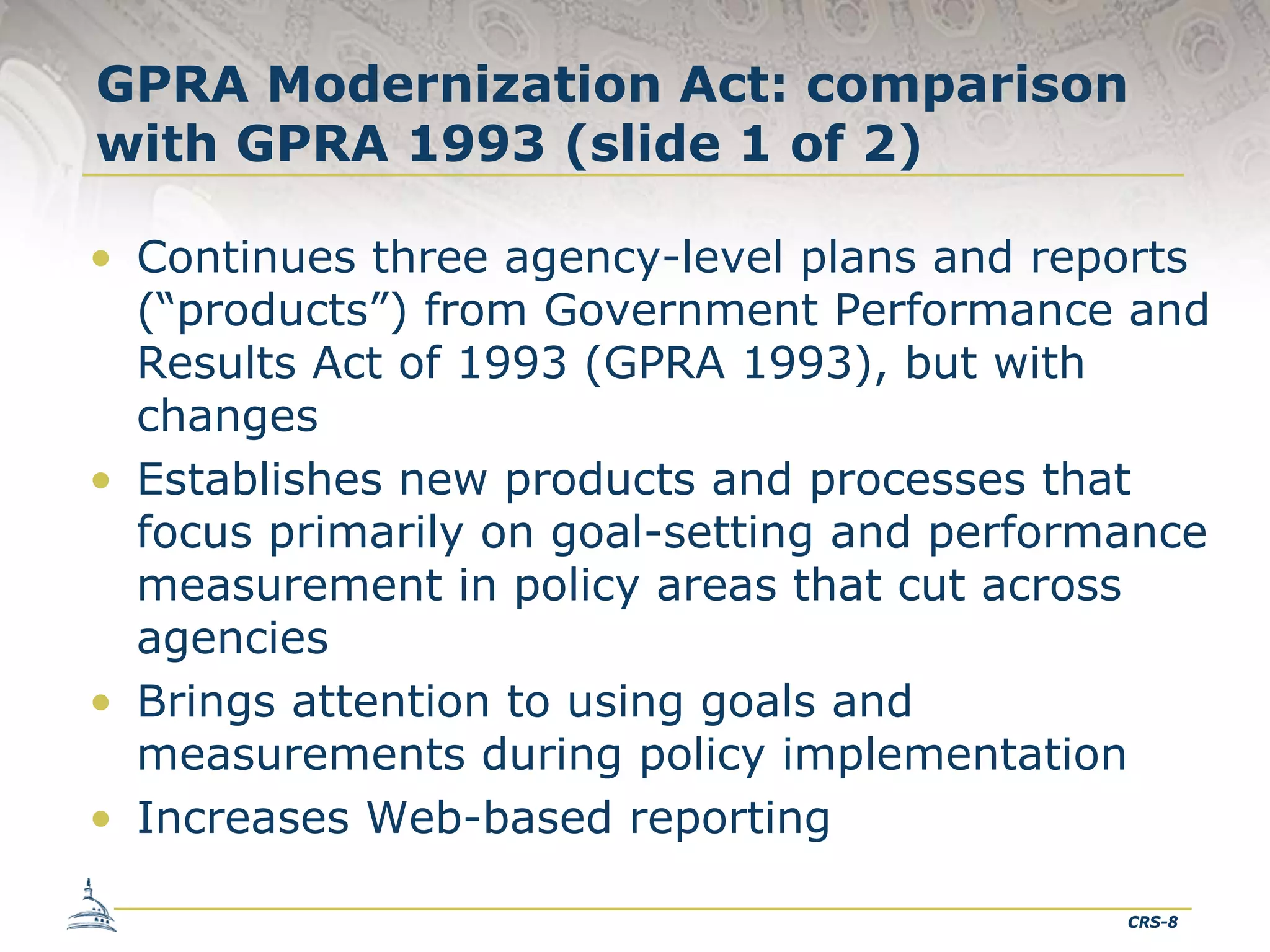

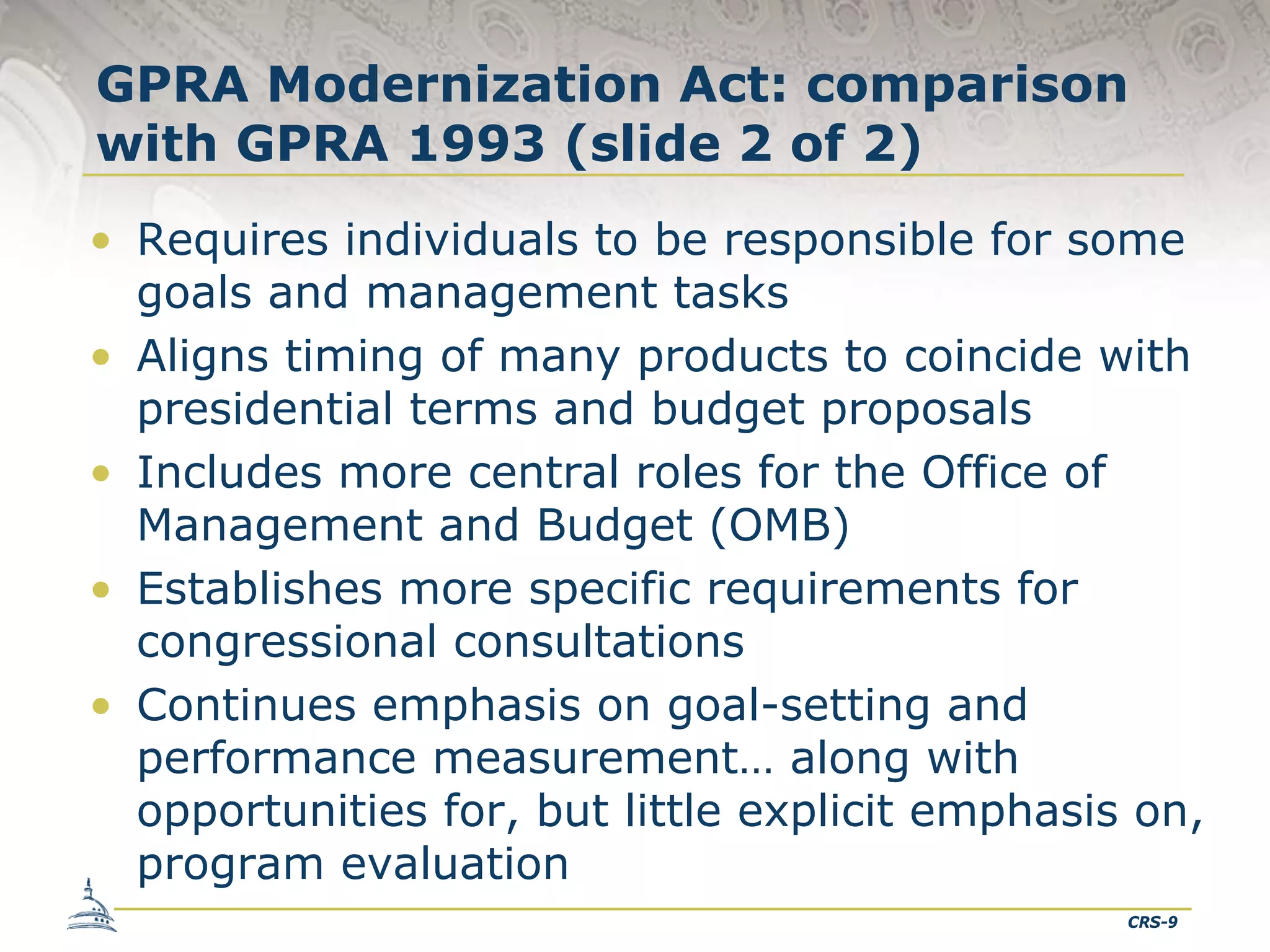

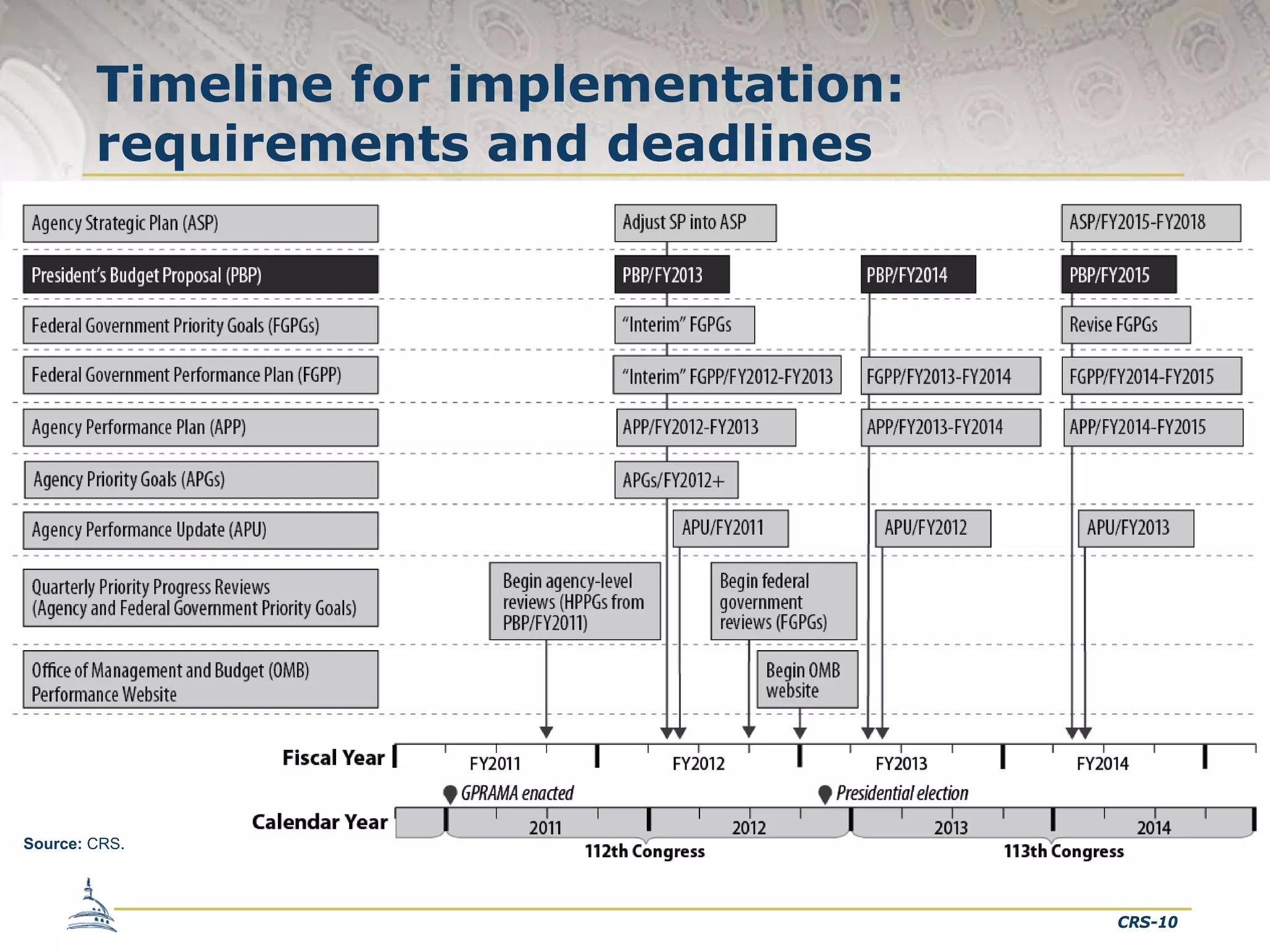

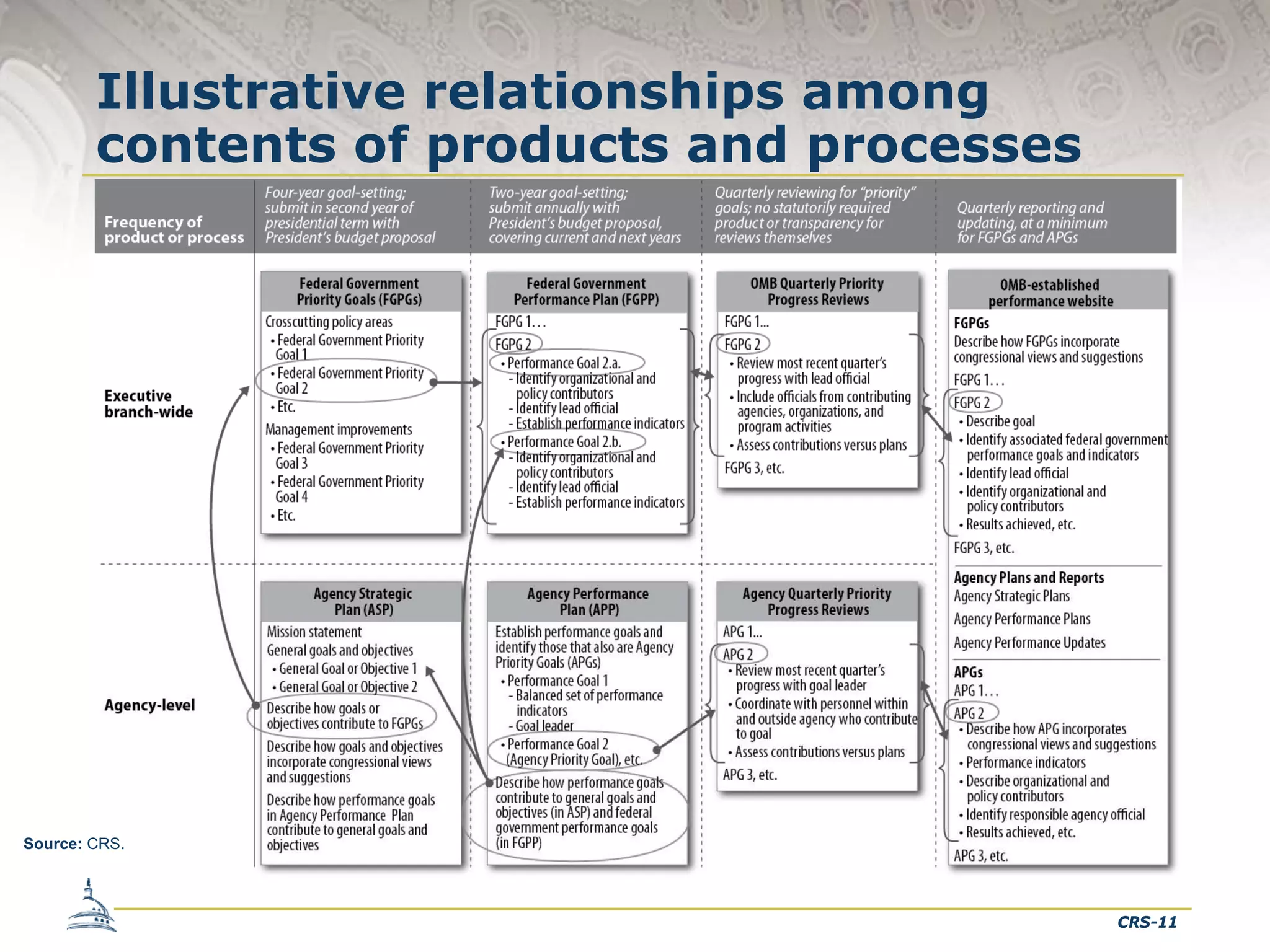

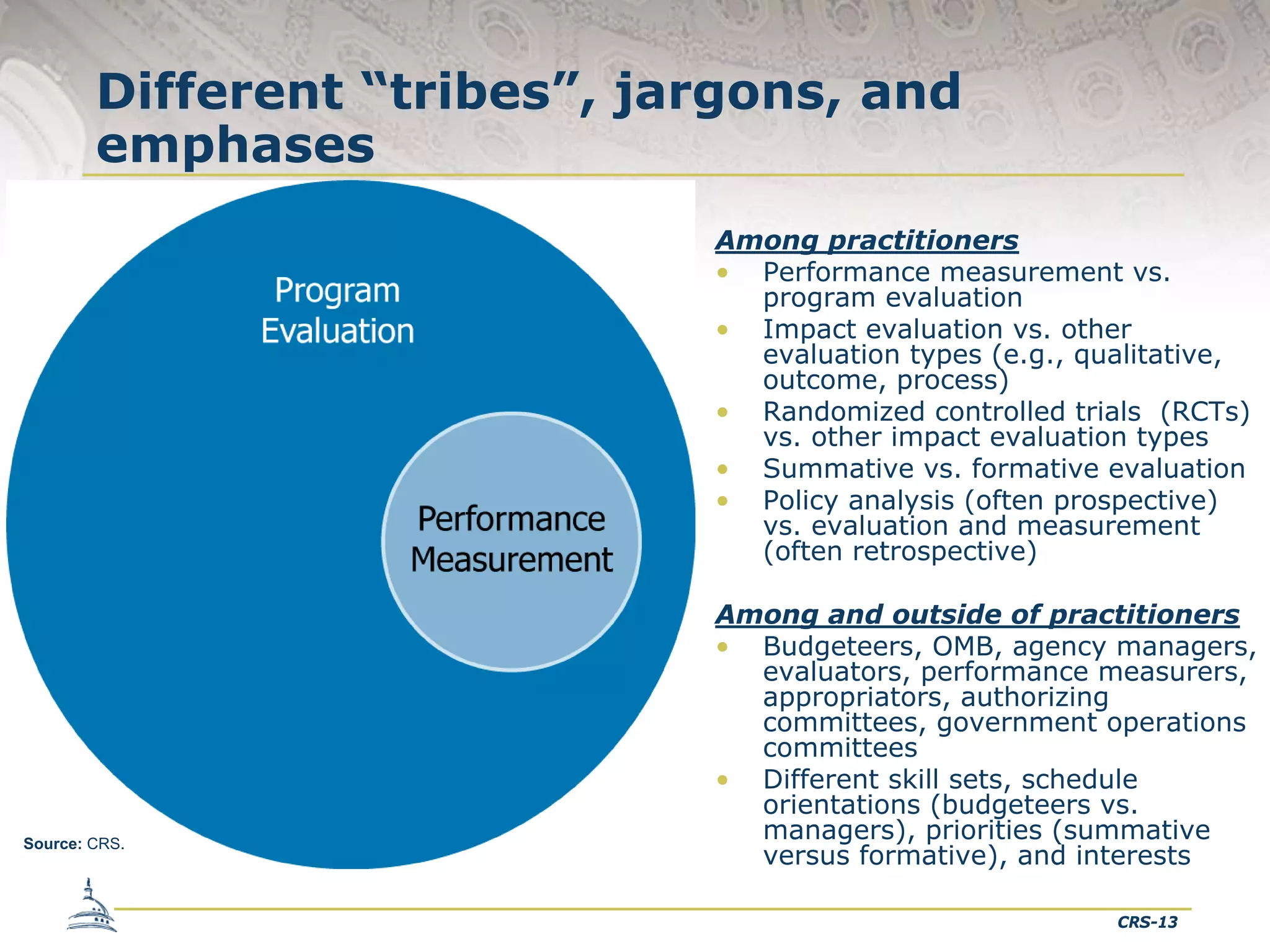

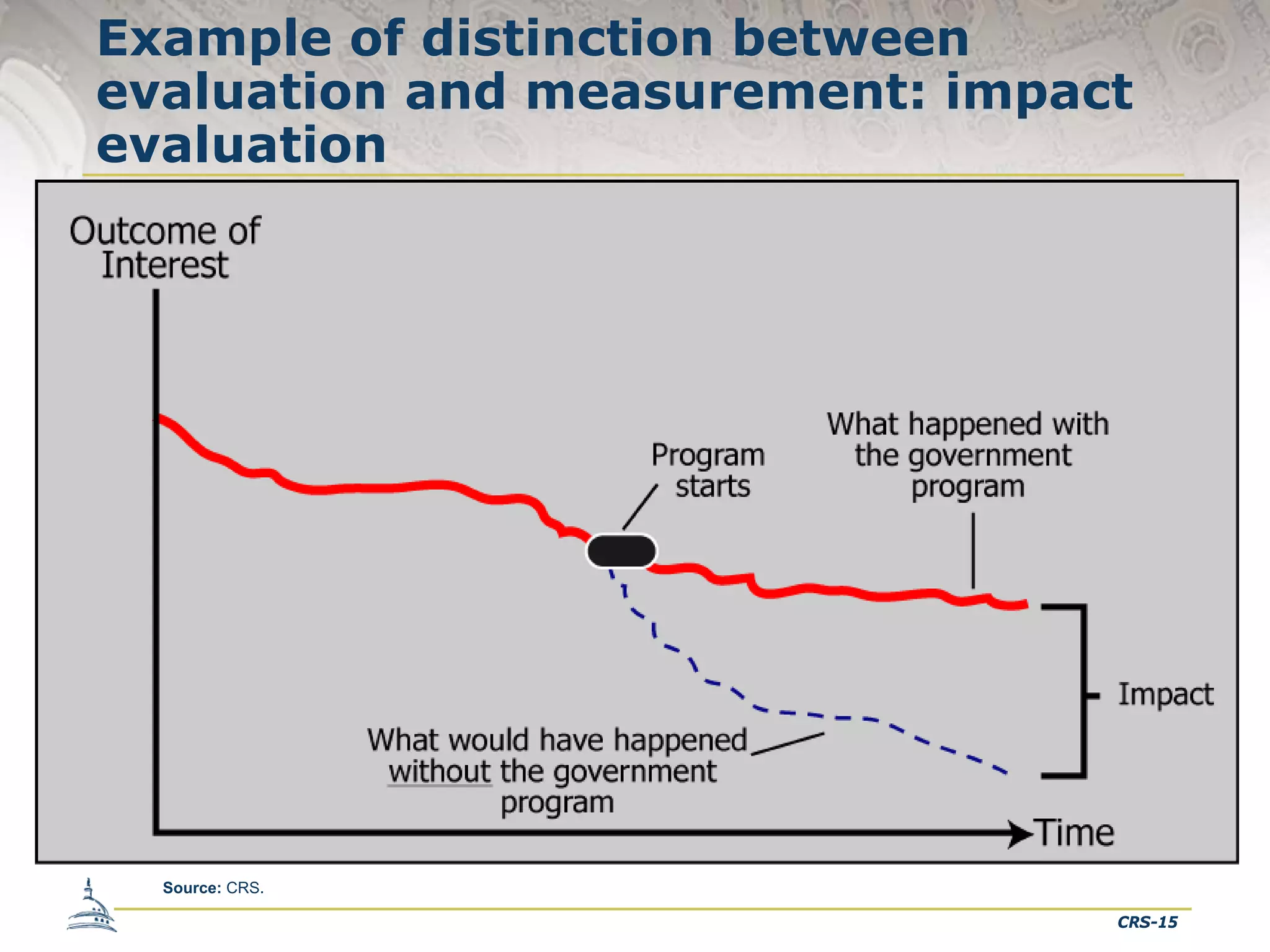

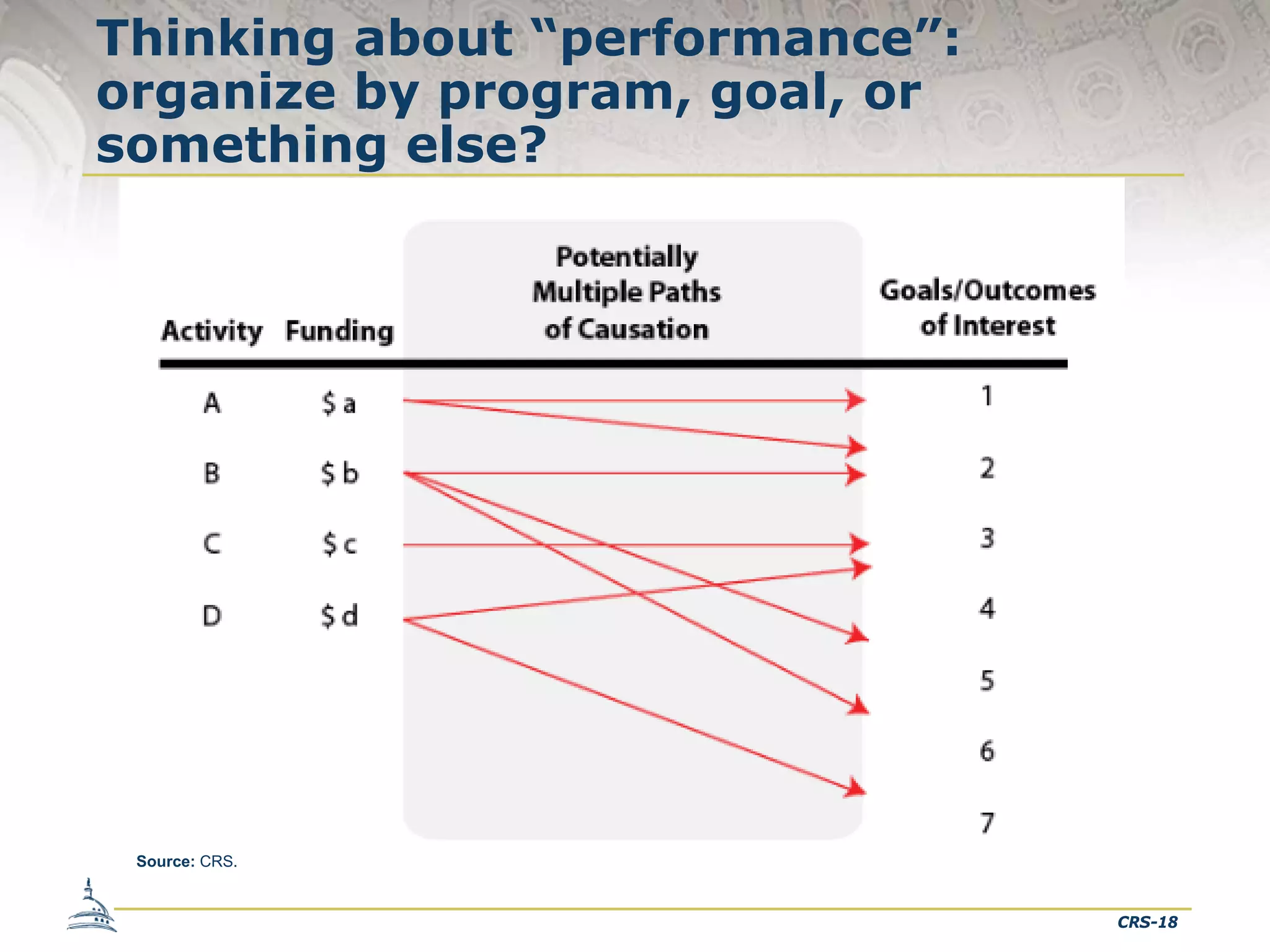

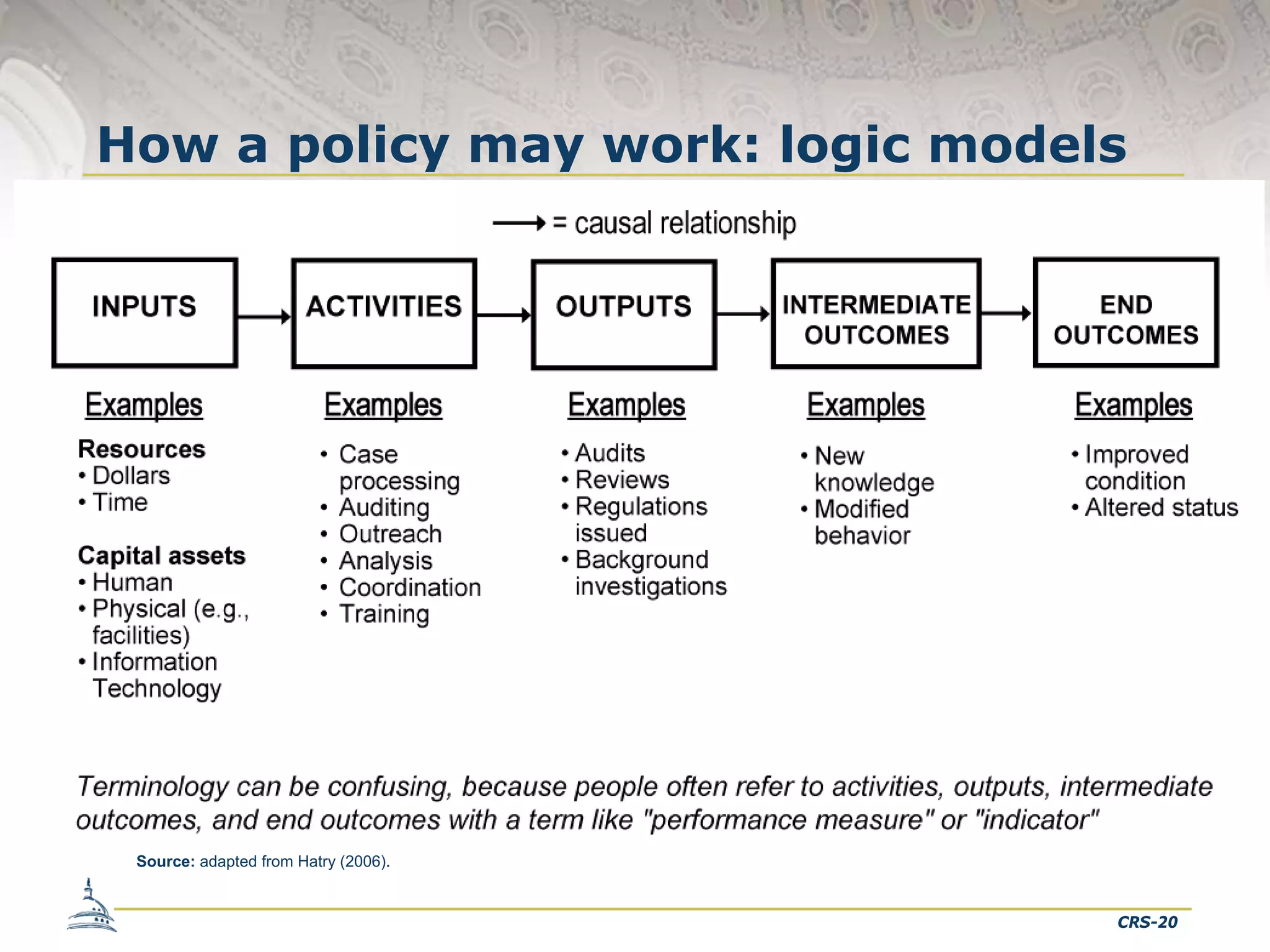

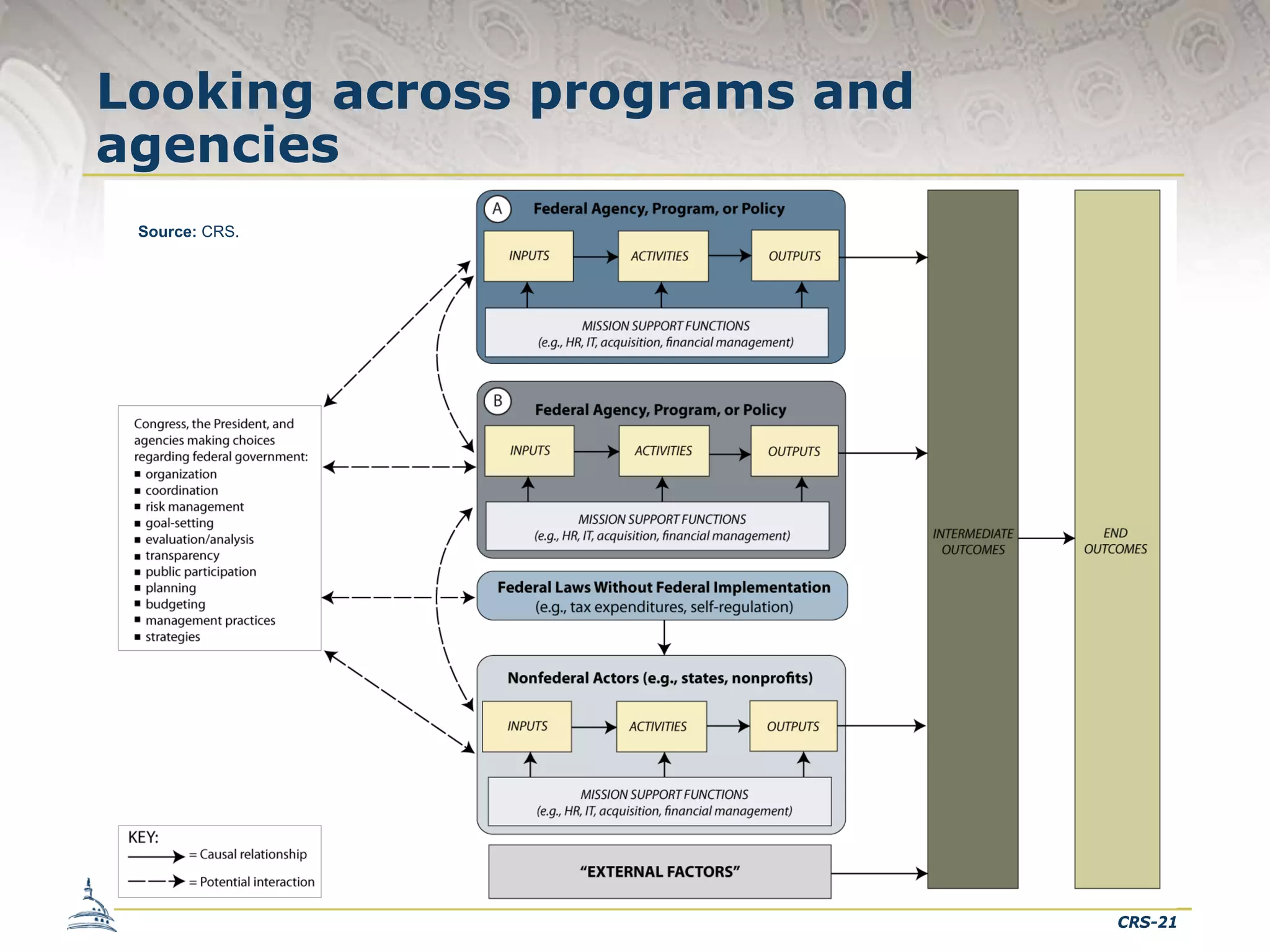

This document provides an overview of a discussion on legislative perspectives on government performance as it relates to the GPRA Modernization Act of 2010. It outlines key aspects of the Act, including its framework, implementation timeline, and relationship to the previous GPRA of 1993. It also examines some threshold issues for practitioners and users, such as different definitions and approaches among "tribes" and potential frameworks for evaluation, measurement, and analysis across programs and agencies. The document concludes by considering issues for Congress related to implementation of the Act.