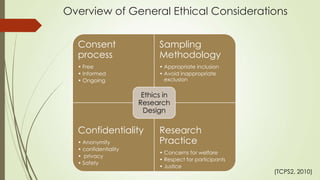

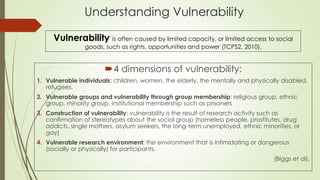

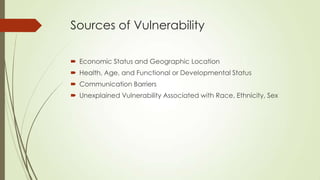

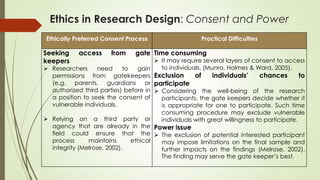

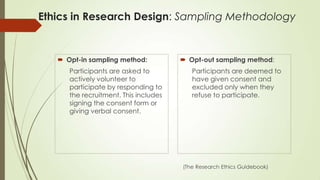

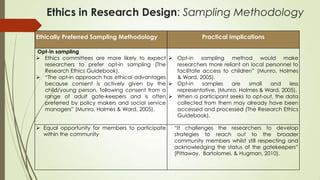

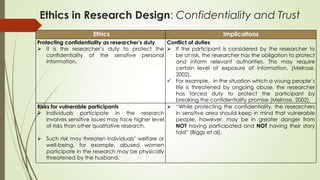

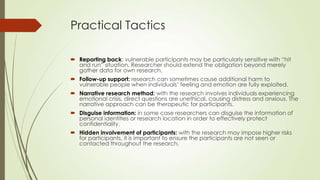

This document discusses ethics considerations for research involving vulnerable groups. It identifies four dimensions of vulnerability and sources of vulnerability. Key ethical issues addressed include obtaining consent, power dynamics, sampling methodology, confidentiality, and research practices. Practical challenges are also discussed, such as time-consuming consent processes potentially excluding participants. Tactics for protecting participants are proposed, like disguising identities, narrative methods, and providing follow-up support. Overall, the document outlines important ethical guidelines to respectfully and equitably involve vulnerable populations in research.