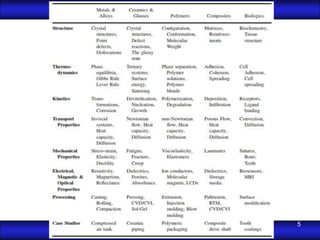

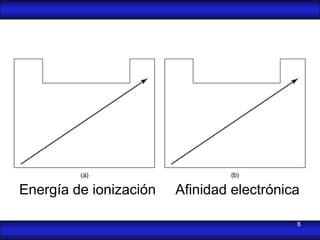

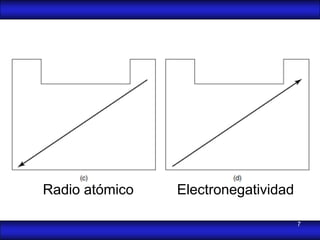

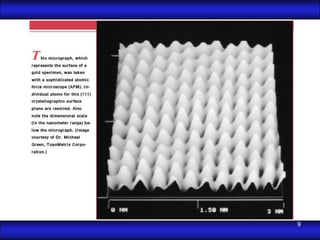

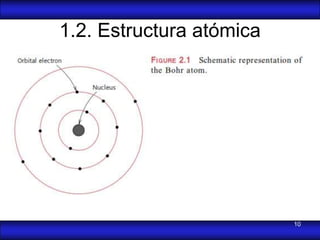

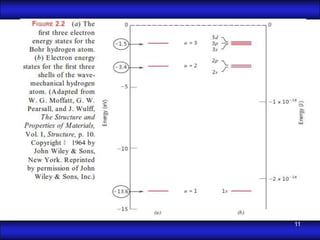

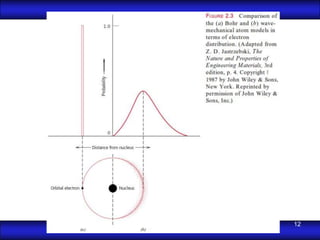

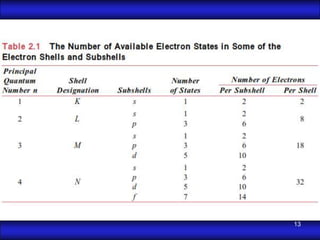

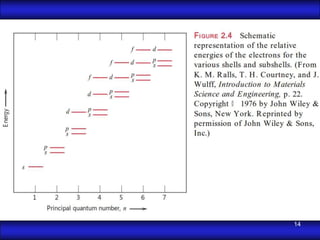

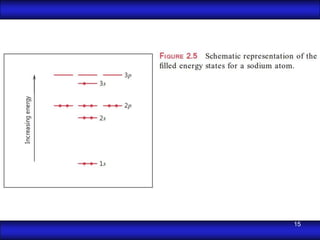

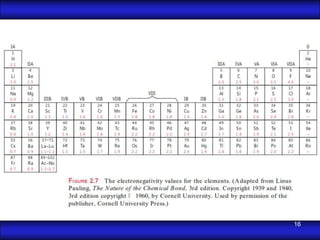

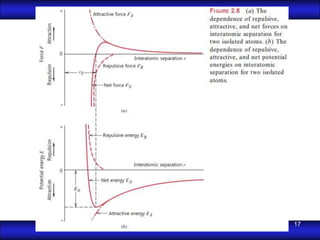

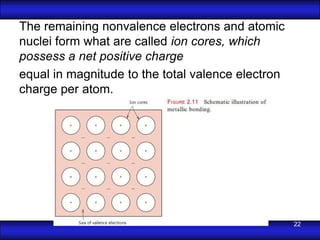

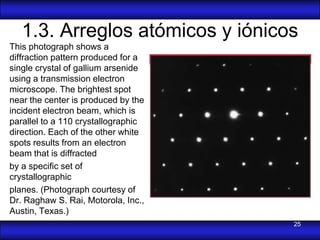

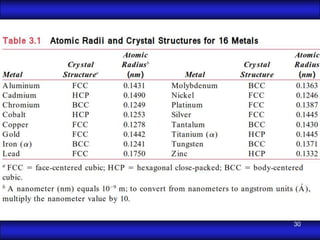

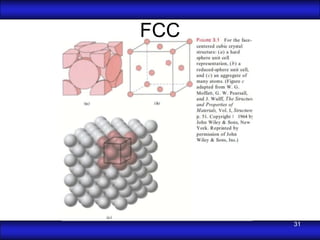

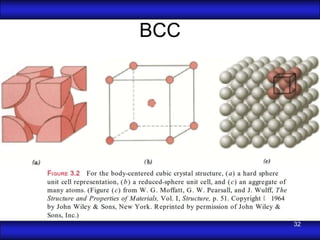

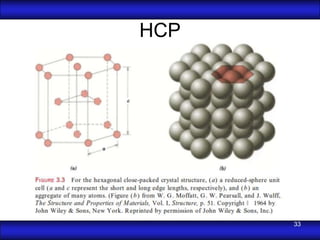

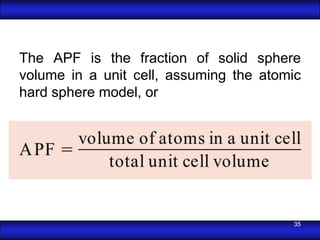

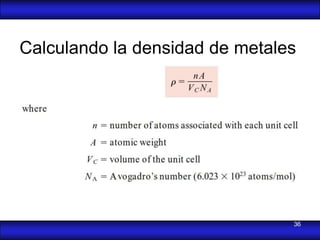

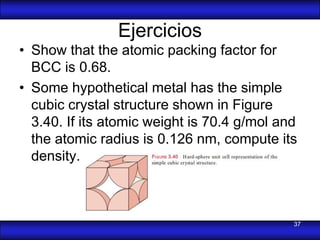

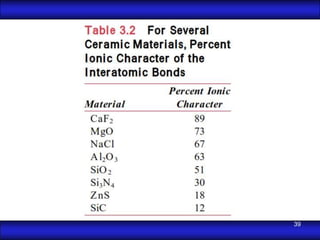

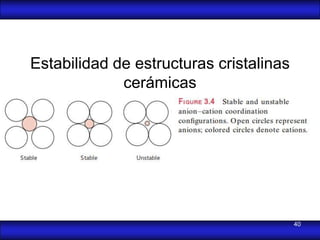

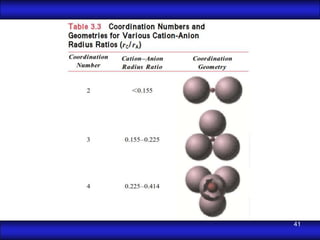

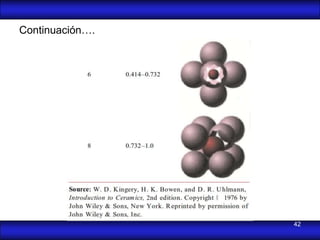

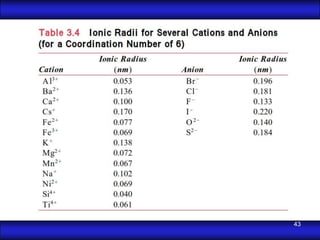

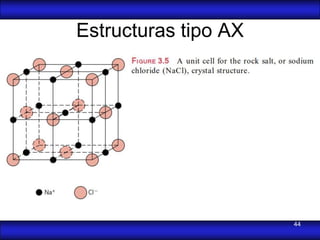

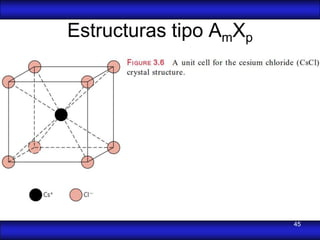

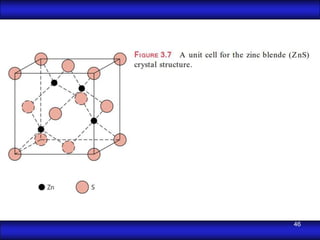

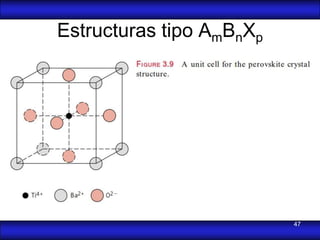

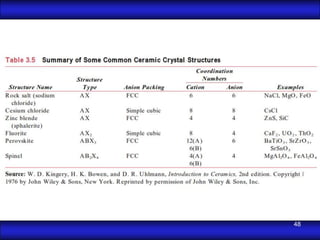

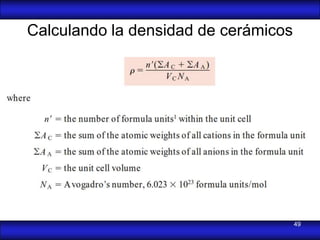

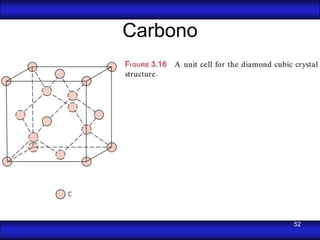

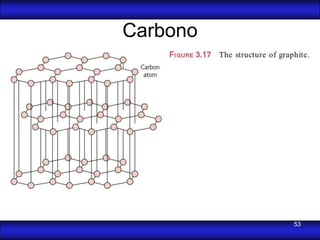

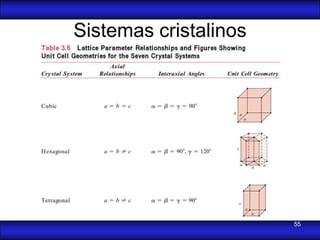

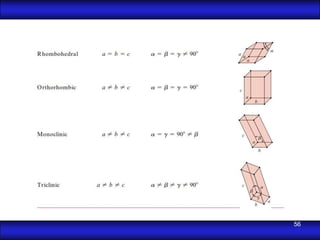

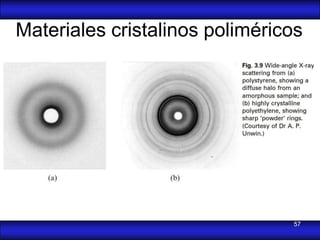

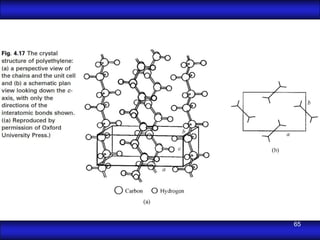

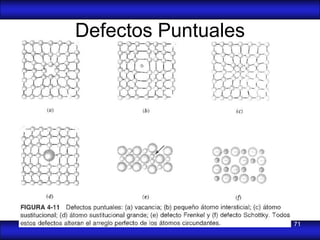

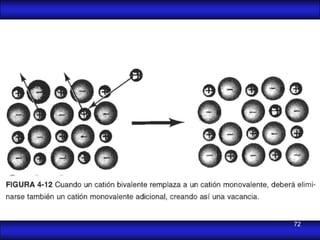

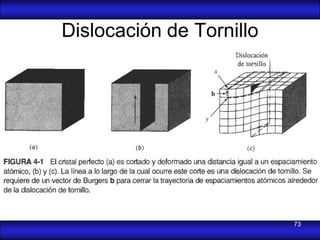

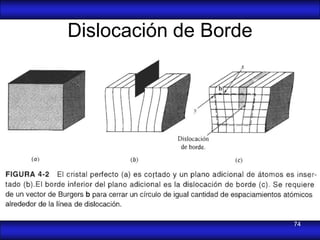

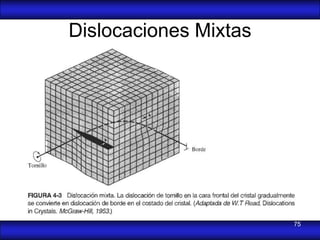

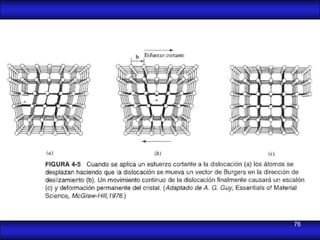

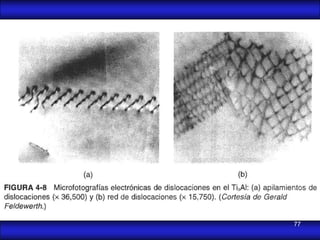

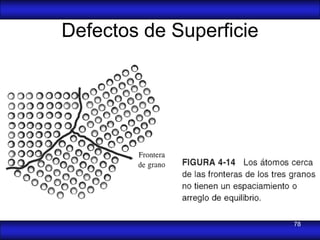

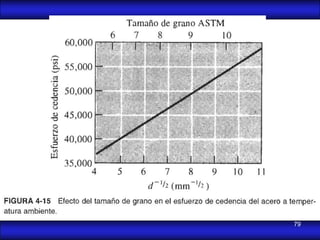

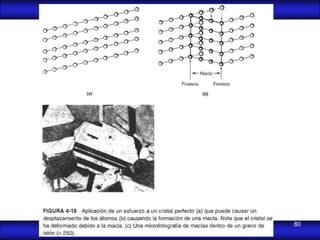

This document is the first unit of a course on the structure, arrangements, and movements of atoms taught by Dr. Edgar García Hernández. The unit introduces materials science and engineering concepts. It discusses atomic structure, crystalline arrangements of metals and ceramics, imperfections in crystals like point defects and dislocations, and atomic movements in solids under mechanical treatments. The unit provides information on crystal structures, unit cells, coordination numbers, and calculating material properties based on structure.