This document summarizes a study that examined the effects of different antifreeze additives on the physical and mechanical properties of concrete produced in cold weather. Concrete samples containing various antifreeze additives were exposed to freezing temperatures between 0 and -20 degrees Celsius. The samples were then cured at room temperature and tested on the 28th day to determine properties like permeability, strength, and elasticity. The study found that a mixture of 30% calcium nitrate and 5% hydroxyethylamine provided the best performance as an antifreeze additive. However, all antifreeze types had a negative impact on concrete properties due to the freezing temperatures during curing.

![The effects of antifreeze use on physical and mechanical properties

of concrete produced in cold weather

Mustafa Çullu a,⇑

, Metin Arslan b

a

Gumushane University, Faculty of Civil Engineering, 29100 Gumushane, Turkey

b

Gazi University, Faculty of Technology, 06500 Ankara, Turkey

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 17 November 2012

Received in revised form 17 January 2013

Accepted 19 February 2013

Available online 27 February 2013

Keywords:

B. Physical properties

B. Mechanical properties

B. Porosity

E. Cure

B. Cure behaviour

a b s t r a c t

This study examined the effects of antifreeze on the physical and mechanical properties of the concrete

which are produced in cold weather. 30% Calcium Nitrate and 5% hydroxyethylaminemixture (HEA), Cal-

cium Nitrate (KN) and Polyhydroxy Amine (PA) were used as additives in antifreeze. Prepared concrete

samples were placed in a formwork and exposed to the frost at 0 °C, 5 °C, 10 °C, 15 °C and 20 °C

for 2 days. Afterwards, concrete samples in the freezer were cured at the room temperature until the

28th day and permeable pore space volume, water absorption ratio, density, capillarity ratio, imperme-

ability, compressive strength, static modulus of elasticity, Poisson’s ratio and tensile strength values of

the concrete samples were determined after the curing. In conclusion, 30% Calcium Nitrate and 5%

hydroxyethylaminemixture (HEA) were found to be giving the best performance among the antifreeze

types. The physical and mechanical properties of the concrete were negatively affected from all antifreeze

types due to the temperature decrease of the exposed fresh concrete.

Ó 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The method and time of placing the concrete into the formwork

and the curing conditions significantly affect the physical and

mechanical properties of the concrete, regardless of the materials

used in the composition of concrete [1].

Portland cement cannot harden under a freezing point without

some thermal protection. For this reason, fresh concrete should be

protected if it is below the freezing point. Protection procedures

can be performed with an insulation material or by increasing

the internal temperature of the concrete over 5 °C. Temperature

should definitely be conserved in emergency conditions. If the con-

crete is not protected from the cold, it freezes and might cause a

disaster [2].

Concrete is widely used in buildings, which are constantly ex-

posed to temperature and moisture. The mechanical and physical

properties of the concrete vary according to environmental condi-

tions in the production period and in curing conditions [3].

The literature contains a large body of research to explain the

freezing mechanism of concretes [4]. Most of the studies showed

that aggregate voids and the transitions between cement paste

aggregate interfaces affect the freezing of concrete. Concrete is af-

fected from frost according to the multiplicity of pores on the

materials composing the concrete which are large enough to allow

penetration of water [5,6]. In cold weather, the water inside these

pores freezes and thus expands. As it is known, approximately a 9%

increase in volume occurs when water turns into ice. Accordingly,

if freezing occurs when 91% or more of the volume of the pores in-

side the concrete are filled with water, the volume of the water will

not fit in the existing volume when it turns into ice, as it will apply

pressure to the surrounding. Since some of the water turns into ice

and causes an increase in volume, it pushes the water which has

not yet turned into ice in an outwardly direction and creates a high

level of hydraulic pressure. This hydraulic pressure might cause

hardened cement paste, which surrounds the aggregate and aggre-

gate grain inside the concrete causes it to crack [5–7]. On the other

hand, researchers reported that concrete was less affected by frost

damage when a concrete with high density and an impermeable

surface is obtained [8,9].

Considerable progresses have been made in the production,

placing, curing and protection of concrete under cold air condi-

tions. As a result, firms do not need to take a break to place the con-

crete in cold weather [10].

Since the temperature of the material components of the con-

crete will have be low temperature in cold weather, the tempera-

ture of the concrete produced also becomes low. The ideal

temperature for casting concrete is 15–16 °C degrees and the tem-

peratures which are considered normal when varying between 5

and 32 °C. At temperatures lower than +5 °C, chemical reactions

between cement and water significantly decrease. Due to the

deceleration of the hydration of cement at low temperatures, the

1359-8368/$ - see front matter Ó 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.02.012

⇑ Corresponding author. Tel.: +90 456 2337425/6/1133; fax: +90 456 2337427.

E-mail address: mcullu@gumushane.edu.tr (M. Çullu).

Composites: Part B 50 (2013) 202–209

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Composites: Part B

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/compositesb](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ullu2013-230730163214-0337dd23/75/ullu2013-pdf-1-2048.jpg)

![setting time becomes longer. Since low hydration speed deceler-

ates the formation of calcium–silicate–hydrate (C–S–H) gels, which

is the most important component of hydration and has a bonding

property, it results in a delayed resistance acquisition. Acquiring

the desired resistance at a delayed time negatively affects the

properties of concrete and delays the time taken for the removal

of the mold [11].

When water inside the concrete completely turns into ice with-

out setting, there will be no water adequate for hydration, as

hydration completely stops and concrete volume expands. After a

certain time, if the ice inside the concrete dissolves and turns into

water due to temperature increase, concrete can set and harden.

However, in such cases, since void volume which occurs due to

melting of ice will be quite large and gels which are the products

of hydration, it will fail to fill these voids adequately, causing a de-

crease in the resistance of the concrete, and thus water imperme-

ability increases [12].

However, if the concrete which set does not gain enough resis-

tance when it freezes, then a cracked and low-resistant concrete is

obtained as the water in capillary voids freeze and expand. Various

researchers suggest 5–14 MPa as an adequate compressive

strength. Another method is to determine how many days later

concrete samples, which are kept at different temperatures, remain

undamaged by frost. However, in cases where the concrete which

started setting did not reach a sufficient level of resistance, a loss of

resistance is expected in the concrete. The freezing of water in a

concrete with adequate resistance for once does not cause cracks

and does not affect resistance. This is explained by the fact that

water inside the concrete with a sufficient degree of resistance is

used for hydration and thus the amount of water decreases.

According to ACI 306R-88 (Cold Weather Concreting), to avoid a

concrete which was exposed to frost once from being damaged,

its resistance should reach a minimum of 3.5 MPa. A concrete with

a good mixture ratio at +10 °C can reach 3.5 MPa resistance 2 days

after placing it [12–15].

As an alternative, antifreeze additives can be used in cold

weather. These chemical additives repress the freezing point of

water under 0 °C degrees and accelerate the hydration of cement;

however, the long-term effects of these additives remain unknown

[2]. Concrete antifreeze additives are an indispensable component

of concrete, particularly in winter and in areas with a cold climate.

The overall effects of these additives, which are thought to have

overall positive effects, should be determined and these effects

should be taken into account in the design process [16].

In parallel to these advancements, the present study examined

the physical and mechanical properties of the concrete with anti-

freeze additives which were exposed to frost. To achieve this goal,

the permeable pore space volume, water absorption ratio, density,

capillarity ratio, impermeability, compressive strength, static mod-

ulus of elasticity, Poisson’s ratio and tensile strength values were

all measured.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Material

2.1.1. Cement

CEM I 42.5R Portland cement was used in the study. The chem-

ical, physical and mechanical properties of the cement are pre-

sented in Table 1.

2.1.2. Aggregate

Limestone aggregate, which is used in the production of normal

resistance concretes in concrete facilities among (0–5, 5–12, 12–

22) aggregate groups were used in the samples. The aggregate

samples were taken according to the principles specified in EN

706 EN 12620 + A1 in such a way as to represent an aggregate heap

[17].

2.1.3. Antifreeze

Three different antifreezes were used in the study. Antifreezes

are chemical additives in compliance with ASTM C 494 and TS

11746 standard [18,19]. Some of the properties of the antifreezes

are presented in Table 2.

2.1.4. Super plasticizer

An additive which is in compliance with ASTM C 494 Type F and

EN 934-2 standards and provides high range water reducer and

early high resistance was used in fresh concrete samples [18–20].

2.2. Method

Antifreeze ratios which will be used for concrete samples for

each type were determined by a preliminary work. Basically, the

antifreeze amount in the concrete mix is approximately 1–2% of

the total mass of the cement. The antifreeze ratios are presented

in Table 3 [21].

After placing the prepared concrete samples in formwork, the

samples were put in a deep freezer within 15 min. They were ex-

posed to frost at 0 °C, 5 °C, 10 °C, 15 °C and 20 °C degrees

in a deep freezer for 2 days. The samples, which were taken out

of the freezer, were then removed from the formwork 1 day later.

They were cured in water at room temperature until the 28th day.

At the end of the curing period, the permeable pore space volume,

water absorption ratio, unit volume weight, capillarity ratio,

impermeability, compressive strength, static modulus of elasticity,

Poisson’s ratio and tensile strength values of the concrete samples

were determined.

2.2.1. Identification of permeable pore space volume

Permeable pore space volume (B0) was calculated on five

100 200 mm cylindrical concrete samples according to ASTM

C642 principles. Eq. (1) was used to calculate B0 [22].

B0 ¼

C A

C D

100 ð1Þ

where B0 is the permeable pore space volume, %, A is mass of oven-

dried sample in air, g, C is mass of surface-dry sample in air after

immersion and boiling, g, D is the apparent mass of sample in water

after immersion and boiling, g [22].

2.2.2. Identification of water absorption

Water absorption ratio (m) was calculated on five

100 200 mm cylindrical concrete samples according to ASTM

C642 principles. Eq. (2) was used to calculate m [22].

m ¼

B A

A

100 ð2Þ

where m is the water absorption ratio by weight, %, A is mass of

oven-dried sample in air, g, B is the mass of surface-dry sample in

air after immersion, g [22].

2.2.3. Identification of density

Density (D) was calculated on five 100 200 mm cylindrical

concrete samples according to EN 12390-7 principles. Eq. (3) was

used to calculate D [23].

D ¼

m

V

ð3Þ

where D is the density of concrete sample, gr/cm3

, m is mass of the

concrete sample depending on its condition during the experiment,

M. Çullu, M. Arslan / Composites: Part B 50 (2013) 202–209 203](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ullu2013-230730163214-0337dd23/75/ullu2013-pdf-2-2048.jpg)

![gr, V is the volume of the concrete sample which is identified by a

special method, cm3

[23].

2.2.4. Identification of the capillarity ratio

Capillarity ratio (I) was performed on five 100 200 mm cylin-

drical concrete samples according to ASTM C1585 principles. Eq.

(4) was used to calculate capillarity ratio I [24].

I ¼ mt=ða=dÞ ð4Þ

where I is the absorption, mt is change in specimen mass in grams at

the time t, a is exposed area of the specimen, in mm2

, d is the den-

sity of the water in g/mm3

[22].

2.2.5. Identification of impermeability

Six 150 150 150 mm cubic concrete samples prepared

according to the principles in EN 12390-8 were placed in a perme-

ability device where pressurized water would be applied. The sam-

ples were exposed to five bars (500 kPa) of pressurized water for

72 h. At the end of this period, concrete samples were split verti-

cally to the surface, on which pressurized water was applied. The

area the water took inside the concrete was marked. The depth

of permeability was determined by measuring the greatest depth

water penetrated starting from the experimental area on which

pressure was applied [25].

2.2.6. Identification of compressive strength

Compressive strength (fc) was calculated on five 100 200 mm

cylindrical concrete samples according to EN 12390-3 principles.

Eq. (5) was used to calculate fc [26].

fc ¼ F=Ac ð5Þ

where fc is the compressive strength, MPa, F is total maximum load,

N, Ac is the area of loaded surface, mm2

[26].

2.2.7. Identification of static modulus of elasticity

Static modulus of elasticity (E) was calculated on five

100 200 mm cylindrical concrete samples according to ASTM

C469 principles. Eq. (6) was used to calculate E [27].

E ¼ ðS2 S1Þ=ð2 0:000050Þ ð6Þ

where E is the chord modulus of elasticity, psi, S2 is stress corre-

sponding to 40% of ultimate load, S1 is stress corresponding to a lon-

gitudinal strain, 1, of 50 millionths, psi, 2 is the longitudinal strain

produced by stress S2 [27].

2.2.8. Identification of Poisson’s ratio

Poisson’s ratio (l) was calculated on five 100 200 mm cylin-

drical concrete samples according to ASTM C469 principles. Eq.

(7) was used to calculate l [27].

l ¼ ðt2 t1Þ=ð2 0:000050Þ ð7Þ

where l = Poisson’s ratio, t2 = transverse strain at midheight of the

specimen produced by stress S2, t1 = transverse strain at midheight

of the specimen produced by stress S1, 2 = longitudinal strain pro-

duced by stress S2 [27].

Table 1

Chemical, physical and mechanical properties of CEM I 42,5R.

Chemical properties Physical properties

SiO2 (%) 20.32 Setting time, initial (min) 01:58

Al2O3 (%) 5.59 Setting time, final (min) 02:57

Fe2O3 (%) 3.09 Volume stability (mm) 2

CaO (%) 62.50 Specific surface (blaine), (cm2

/g) 3172

MgO (%) 1.74 Specific gravity (g/cm3

) 3.09

SO3 (%) 3.29

Na2O (%) 0.34

Mechanical properties Comp. strength (MPa)

K2O (%) 0.91 Basýnç dayanýmý (MPa)

Loss on ignition (%) 1.18 2 days 30.8

Insoluble residue (%) 0.31 7 days 39.5

S CaO (%) 0.93 28 days 56.0

Table 2

Antifreeze type and properties.

Additive no. Additive code Chemical content Properties

1 HEA 30% Calcium Nitrate + 5% hydroxyethylaminemixture Density: 1.25 ± 0.03 kg/L

pH: 6.00–6.50

Chloride: 60.1% (EN 480-10)

Alkali content: 610% (EN 480-12)

2 KN Calcium Nitrate Density: 1.25 ± 0.03 kg/L

pH: 6.00–8.00

Chloride: 60.1% (EN 480-10)

Alkali content: 610% (EN 480-12)

3 PHA Polyhydroxy Amine Density: 1.25 ± 0.03 kg/L

pH: 6.00–6.50

Chloride: 60.1% (EN 480-10)

Alkali content: 610% (EN 480-12)

Table 3

Antifreeze ratios to be used in mixtures [21].

Antifreeze type Curing temperature °C

0 °C (%) 5 °C (%) 10 °C (%) 15 °C (%) 20 °C (%)

HEA 1 1 1 1 1

KN 1 1 2 2 2

PHA 1 1 1 1 1

204 M. Çullu, M. Arslan / Composites: Part B 50 (2013) 202–209](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ullu2013-230730163214-0337dd23/75/ullu2013-pdf-3-2048.jpg)

![2.2.9. Identification of tensile strength

Tensile strength (T) was calculated on five 100 200 mm cylin-

drical concrete samples according to ASTM C496 principles. Eq. (8)

was used to calculate E [28].

T ¼ 2P=pld ð8Þ

where T = splitting tensile strength, MPa, P = maximum applied load

indicated by the testing machine, N, l = length, mm, d = diameter,

mm [28].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Permeable pore space volume

The permeable pore space volume value increases in parallel to

the decrease in temperature values to which the concrete is ex-

posed. This increase is due to the fact that the water required for

the hydration of cement and thickness of the concrete freezes

and creates a porous structure inside the concrete. A graph of mean

void values is presented in Fig. 1.

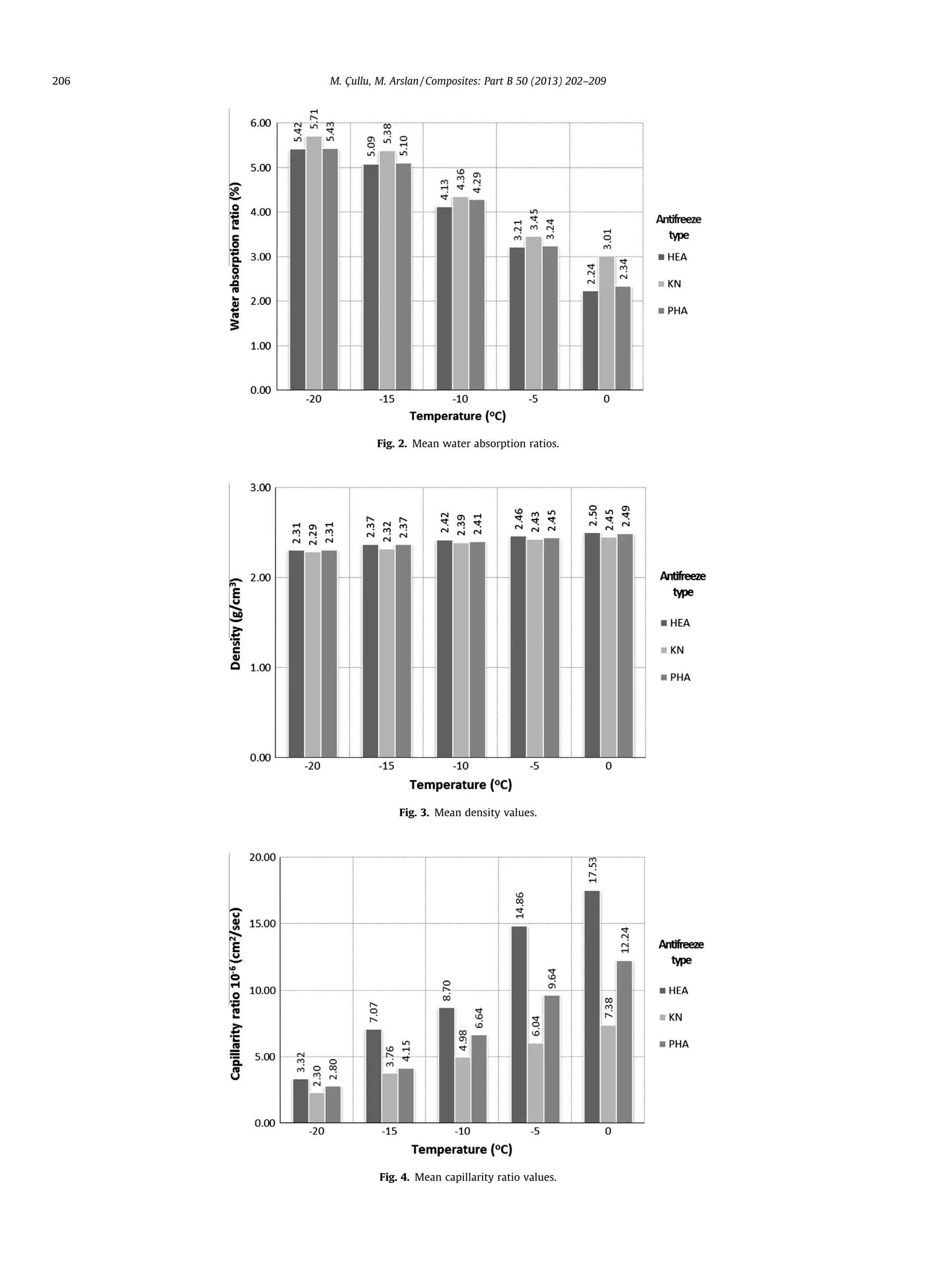

3.2. Water absorption ratio

The water absorption ratio value increases in parallel to the de-

crease in temperature value to which the concrete is exposed. The

reason for this increase is the increasing void structure due to the

temperature decrease to which the concrete was exposed. The

graph for the mean water absorption values are presented in Fig. 2.

3.3. Density

The density values decrease in parallel to the decrease in tem-

perature values to which the concrete is exposed. The reason for

this decrease is increased void structure due to the decrease of

temperature to which the concrete is exposed. The graph for the

mean density values is presented in Fig. 3.

3.4. Capillarity ratio

The capillarity ratio value decreases in parallel to the decrease

in temperature value to which the concrete is exposed. The reason

for this decrease is the increased void structure due to decrease in

temperature to which the concrete was exposed. Accordingly, the

capillarity ratios of concrete samples decrease. In addition, the

graph of mean capillarity ratio is presented in Fig. 4.

3.5. Impermeability

The impermeability value increases in parallel to the decrease

of temperature to which the concrete is exposed. The reason for

this increase is the increasing void structure due to the decrease

in temperature to which the concrete is exposed. If pressurized

water is applied to porous concrete, water penetration depth in-

creases. The graph for the mean impermeability values are pre-

sented in Fig. 5.

3.6. Compressive strength

The compressive strength values decrease in parallel to the de-

crease of temperature values which the concrete is exposed. The

reason for this decrease is the decrease of compressive strength

due to the decrease of the temperature. The maximum decrease

of the compressive strength is observed for the concrete samples

which are exposed to 20 °C. The maximum decrease of the com-

pressive strength is observed at the specimens which are exposed

to 20 °C. The graph for the mean compressive strength values is

presented in Fig. 6.

3.7. Static modulus of elasticity

The static modulus of elasticity values decrease in parallel to

the decrease in temperature values of the exposed concrete. The

reason for the decrease of static modulus of elasticity is observed

due to the decrease of temperature of the exposed concrete. Simi-

lar to the results of the compressive strength experiments, with the

decrease of the temperature which the concrete is exposed, static

modulus of elasticity is decreased. The graph for the mean static

modulus of elasticity values is presented in Fig. 7.

3.8. Poisson’s ratio

The Poisson ratio values decrease in parallel to the decrease in

temperature which the concrete is exposed. The reason for the de-

crease of Poisson’s ratio is observed due to the decrease of temper-

ature of the exposed concrete. The temperature decrease of the

fresh concrete yields a decrease of the compressive strength and

static modulus of elasticity of the concrete specimens. The decreas-

Fig. 1. Mean permeable pore space volume.

M. Çullu, M. Arslan / Composites: Part B 50 (2013) 202–209 205](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ullu2013-230730163214-0337dd23/75/ullu2013-pdf-4-2048.jpg)

![ing compressive strength also yields a greater deformation of the

specimens hence Poisson’s ration is increased. The graph for the

mean Poisson’s ratio values is presented in Fig. 8.

3.9. Tensile strength

The tensile strength values decrease in parallel to the decrease

in temperature values to which the concrete is exposed. The reason

for this decrease is the decrease of the tensile strength value of the

specimens due to the decreasing temperature of the exposed con-

crete specimens. The graph for the mean tensile strength values is

presented in Fig. 9.

4. Conclusion

The following results were obtained according to the frost con-

ditions to which fresh concrete was exposed.

Considering the effects of all antifreeze types used in concrete

mixtures on the physical and mechanical properties of the con-

crete, 30% Calcium Nitrate and 5% hydroxyethylaminemixture

(HEA) gave the best performance.

If fresh concrete is exposed to frost, water is required to achieve

the hydration of cement and thickness of concrete freezes and

creates a porous structure inside the concrete (Turhan [12]).

The permeable pore space volume value increases in accordance

with the decrease in temperature value to which the concrete is

exposed.

It was observed that water absorption ratio of porous concrete

increased regarding to the permeable pore space volume value.

It was observed that, porous structures inside the concrete also

decreased the unit volume weight of the concrete.

The amount of capillary absorbed water decreases in accor-

dance with the decrease in temperature to which fresh concrete

is exposed. The reason for this might be that the voids which are

formed due to the freezing of the water inside the concrete dur-

Fig. 8. Mean Poisson’s ratio values.

Fig. 9. Mean tensile strength values.

208 M. Çullu, M. Arslan / Composites: Part B 50 (2013) 202–209](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ullu2013-230730163214-0337dd23/75/ullu2013-pdf-7-2048.jpg)

![ing hydration cut the capillary canals and thus a decrease in the

amount of water penetrating the concrete through the capillary

method is decreased.

Considering impermeability, if pressurized water is applied on

the surface of concrete, the amount of water which penetrates

the concrete decreased due to the porous structure inside the

concrete during hydration process.

The exposure of the fresh concrete to frost not only affect the

physical properties but also the mechanical properties. With

the decrease of the temperature which the concrete is exposed,

compressive and tensile strength values, static modulus of elas-

ticity values are also decreased.

The exposure of fresh concrete to frost has a negative impact on

the concrete’s physical and mechanical properties. These con-

cretes should be absolutely protected. Otherwise, the physical

and mechanical properties which are expected from the con-

crete cannot be achieved, and thus, concrete fails to show an

adequate resistance to negative environmental and corrosive

environments.

References

[1] Subas

ßı S, Koçak Y, Beycioğlu A. The effect of vibration period on physical and

mechanical properties at fly ash replaced concrete. Dumlupınar Univ J Inst Sci

Technol Ağustos 2010;22:109–22.

[2] Korhonen CJ. Expendient low-temperature concrete admixtures for army USA:

US Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research Engineering Laboratory;

1999. p. 1–20.

[3] Shoukry SN, William GW, Downie B, Riad MY. Effect of moisture and

temperature on the mechanical properties of concrete. Constr Build Mater

2011;25:688–96.

[4] Picketh G. Flow of moisture in hardened cement during freezing. Highway Res

Board 1953;32:276–84.

[5] Prado PJ, Balcom BJ, Beyea TW, Armstrong RL, Grattan-Bellew PE. Concrete

freze/thaw as studied by magnetic resonance imagine. Cem Concr Res

1998;2(28):261–70.

[6] Pigeon M, Gagne R, Aitcin PC, Banthia N. Freezing and thawing tests of high

strength concretes. Cem Concr Res 1991;5(21):844–52.

[7] Cai H, Liu X. Freze-thaw durability of concrete: ice formation process in pores.

Res Cem Concr 1998;9(28):1281–7.

[8] Arslan M, Subas

ßı S. The effects of controlled-permeable formworks on the

surface hardness of the concrete. J Fac Eng Arch Gazi Univ 2008;23(4):885–94.

[9] Arslan M, Subas

ßı S, Durmus

ß G. The Effects of formwork surfaces on capillarity

and frost resistance of concrete cover. Ready Mixed Concr J 2002;50:60–6.

[10] Nmai CK. Cold weather concreting admixtures. Cem Concr Compos 1998;2–

3(20):121–8.

[11] Türkel S. Production of concrete in cold weather conditions. In: Earthquake

symposium. Us

ßak; 2003. p. 32–45.

[12] Turhan YE. Concrete. Ankara: METU Press; 2003.

[13] Baradan B, Yazıcı H, Ün H. Concrete and concrete structures persistence

(durability). Izmir: Dokuz Eylül University Engineering Publications; 2002.

[14] ACI Committee 306. ACI 306.R-88 cold weather concreting. American Concrete

Institute. Detroit, Michigan: American Concrete Institute; 1988. p. 1–23.

[15] Suprenant BA. Freezing concrete as a construction practice. Cold Reg Sci

Technol 1985;11(2):195–7.

[16] Yıldırım H, Pekmezci BY, Ardaç V. Contribution of the use of antifreeze effect of

concrete compressive strength of concrete. J Constr Chem Sec 2007;1:66–9.

[17] EN 706 12620+A1. Aggregates for concrete. Ankara: Turkish Standards

Institute; 2009. p. 1–50.

[18] ASTM C 494. Standard specification for chemical admixtures for concrete.

Concrete and mineral aggregates. Annual Book of ASTM Standards.

Philadelphia, USA; 2004. p. 1–10.

[19] TS 11746. Chemical admixtures for concrete antifreezing agents for

concrete. Ankara: Turkish Standards Institute; 1995. p. 1–14.

[20] EN 934-2. Admixtures for concrete, mortar and grout – Part 2: concrete

admixtures – definitions, requirements, conformity, marking and

labelling. Ankara: Turkish Standards Institute; 2011. p. 1–24.

[21] Arslan M, Çullu M, Durmus

ß G. The effect of antifreeze admixtures on

compressive strength of concretes subjected to frost action. Gazi Univ J Sci

2011;24(2):299–307.

[22] ASTM C642. Standard test method for density, absorption, and voids in

hardened concrete. Annual Book of ASTM Standards. Philadelphia, USA; 2004.

p. 1–3.

[23] EN 12390-7. Testing hardened concrete – Part 7: Density of hardened

concrete. Ankara: Turkish Standards Institute; 2010. p. 1–11.

[24] ASTM C1585. Standard test method for measurement of rate of absorption of

water by hydraulic-cement concretes. Annual Book of ASTM Standards.

Philadelphia, USA; 2004. p. 1–6.

[25] EN 12390-8. Testing hardened concrete – Part 8: Depth of penetration of water

under pressure. Ankara: Turkish Standards Institute; 2010. p. 1–7.

[26] EN 12390-3. Testing hardened concrete – Part 3: Compressive strength of test

specimens. Ankara: Turkish Standards Institute; 2010. p. 1–19.

[27] ASTM C469. Standard test method for static modulus of elasticity and

Poisson’s ratio of concrete in compression. Annual Book of ASTM Standards.

Philadelphia, USA; 2002. p. 1–5.

[28] ASTM C496. Standard test method for splitting tensile strength of cylindrical

concrete specimens. Annual Book of ASTM Standards. Philadelphia, USA; 2004.

p. 1–5.

M. Çullu, M. Arslan / Composites: Part B 50 (2013) 202–209 209](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ullu2013-230730163214-0337dd23/75/ullu2013-pdf-8-2048.jpg)