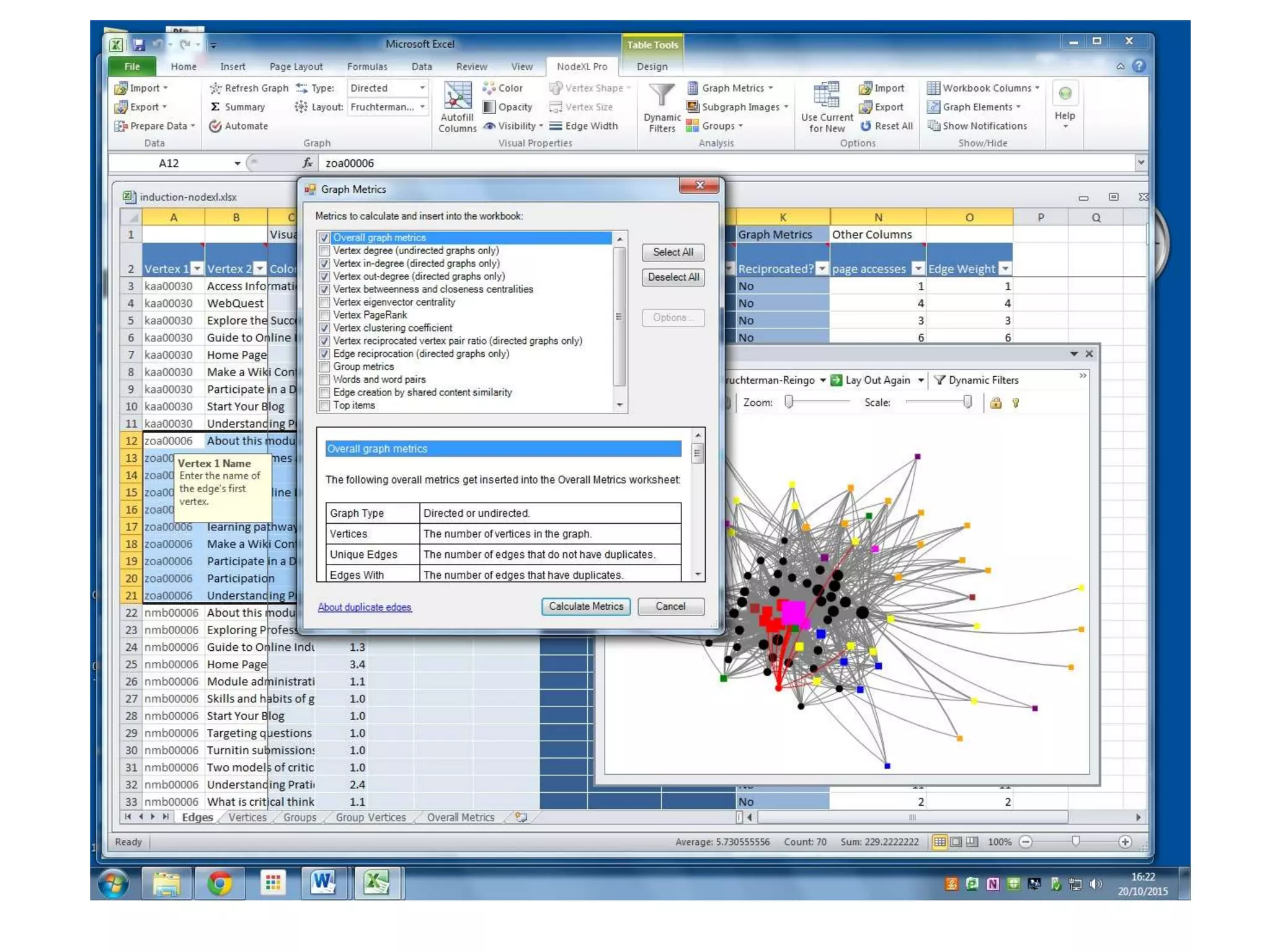

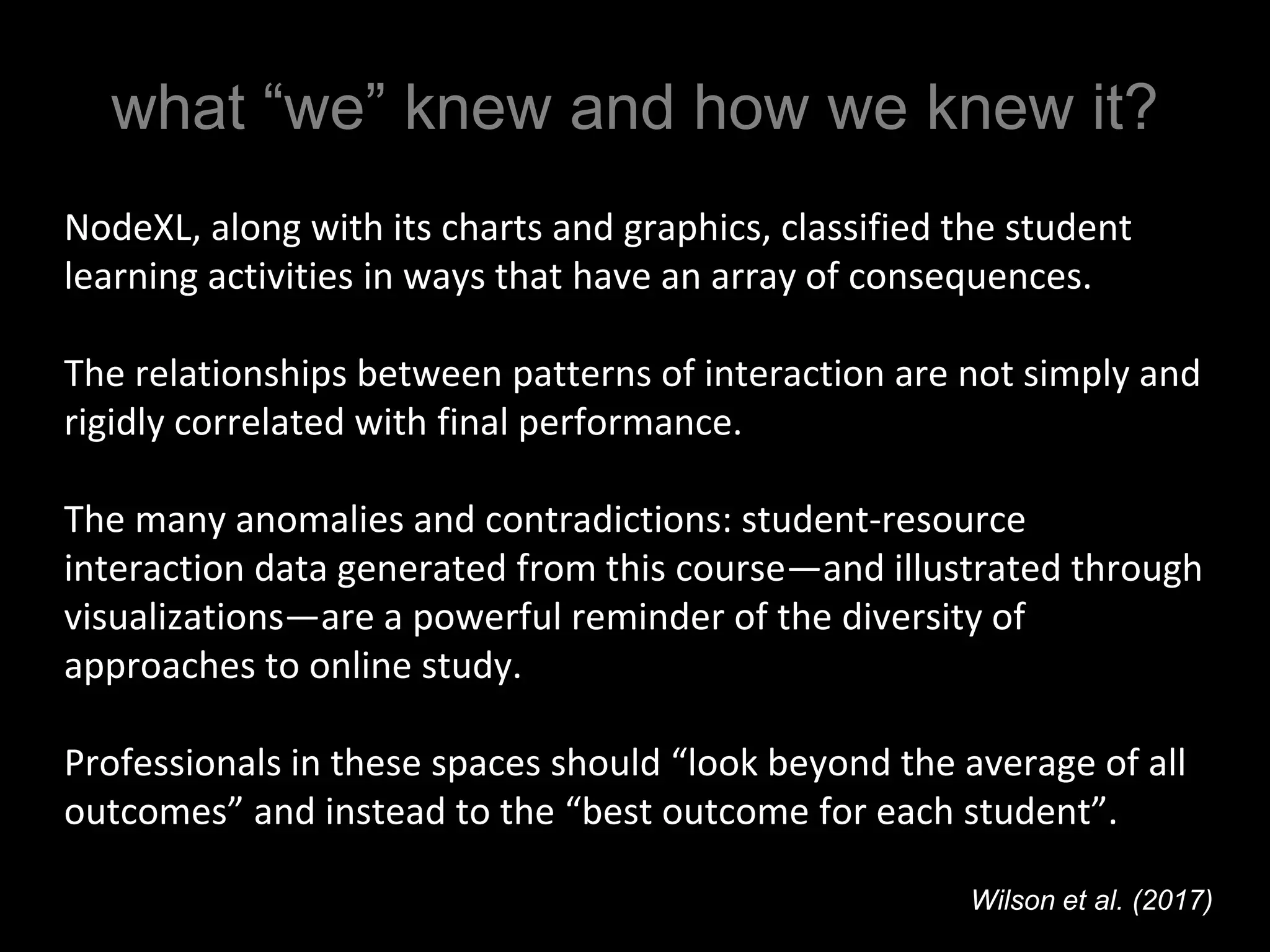

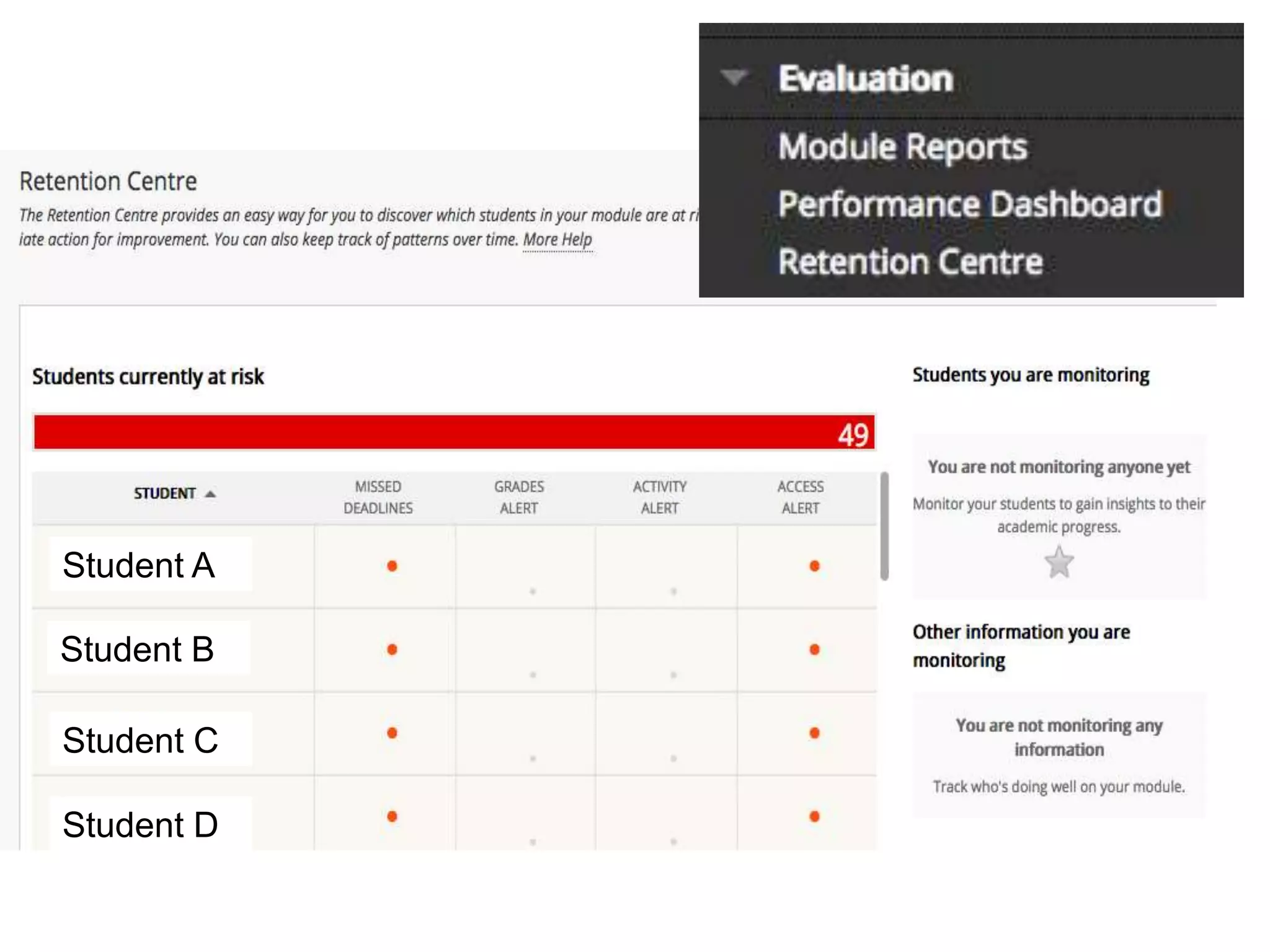

Digital data is increasingly being used to track and analyze human activities like work, learning, and living. This document discusses how the "datafication" of these areas is redistributing responsibilities between humans and algorithms. It explores issues around accountability, control, and transparency when important decisions are made based on data. The author advocates developing new "literacies" to ensure data practices align with public interests and values, and calls for a posthuman perspective that sees humans and technology as deeply entangled.