This thesis compares three radial basis function methods - collocation, Galerkin formulation, and generalized interpolation - for solving convection-diffusion equations. Numerical experiments are performed using different radial basis functions and problem sizes to evaluate the methods' ease of implementation, accuracy, stability, and efficiency. The author finds that while the Gaussian radial basis function achieves high accuracy, it also leads to instability. The compactly supported Wendland functions provide greater stability but reduced accuracy. Overall, the collocation method performs best for the compactly supported functions, while generalized interpolation is most accurate when using the Gaussian basis. The Galerkin method is found to be unstable and inefficient. Possible extensions discussed include methods for selecting the scaling parameter and non

![Chapter 1

Introduction

Radial Basis Function (RBF) methods trace their origins back to Hardy’s multi-

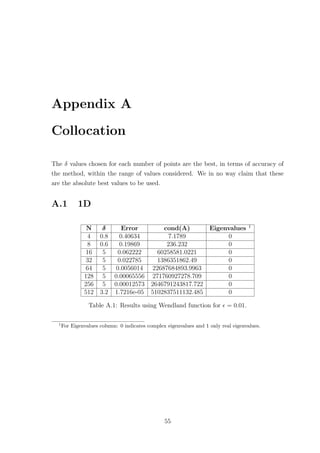

quadric (MQ) method [6]. This method was developed by Hardy as a way to obtain a

continuous function that would accurately describe the morphology of a geographical

surface. The motivation came from the fact that the already existing methods at the

time, like Fourier and polynomial series approximations, provided neither acceptable

accuracy nor efficiency [6], [24]. Moreover obtaining the desired result as a continu-

ous function meant that analytical techniques from calculus and geometry could be

utilised to provide useful results, e.g. the height of the highest hill, unobstructed lines

of sight, volumes of earth and others [6].

In mathematical terms, the problem Hardy was trying to solve can be stated

as: given a set of unique points X = {x1, ..., xn} ∈ Rd

with corresponding values

{f1, ..., fn}, find a continuous function s(x) that satisfies the given value at each

point, i.e., s(xi) = fi for i = 1, .., n. Hardy [6], following a trial and error approach,

constructed the approximate solution by taking a linear combination of the multi-

quadric functions

qj(x) = c2 + x − xj

2

2, j = 1, .., n, (1.1)

where each of these functions is centered about one of the unique points in our set.

The problem therefore reduces to finding the coefficients Cj such that

s(xi) =

n

j=1

Cjqj(xi) = fi, i = 1, .., n, (1.2)

which involves nothing more than solving a system of linear equations. It has been

proved that the system of linear equations resulting from the MQ method is always

nonsingular, see for example, Micchelli [12].

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-12-320.jpg)

![The MQ method, which has found applications in areas other than topography,

has also been used in order to numerically approximate the solution to partial dif-

ferential equations. In fact, Kansa [9] found, after performing a series of numerical

experiments, that the MQ method in many cases outperformed finite difference meth-

ods, providing a more accurate solution while using a smaller number of points and

without having to create a mesh.

After Micchelli [12] provided the conditions under which the resulting linear sys-

tem of Hardy’s method is nonsingular, it was realised that other functions, as well

as (1.1) could also be used with the method. The common characteristic of those

functions is that their value only depends on the distance from a chosen center, i.e.,

they are radially symmetric with respect to that center. These functions are now

widely known as radial basis functions (RBFs).

1.1 Aim of Thesis

The motivation for looking into radial basis function methods for numerically solv-

ing partial differential equations (PDEs) comes from the fact that standard methods,

like finite differences or finite elements, can easily become computationally expensive.

This is a direct result of the requirement of these methods for creating a mesh, and

also the need for having usually a large number of points in order to obtain accept-

able accuracy. The necessity of using a really small stepsize is more evident when the

solution to be approximated has stiff regions. For example, in Figure 1.1 we see the

finite element solution on a uniform mesh to both a 1D and a 2D convection domi-

nated diffusion problem where we get oscillations in the boundary layer. Moreover,

Figure 1.1: Numerical solutions obtained using finite element methods.

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-13-320.jpg)

![the methods become increasingly complex as we take into consideration problems in

higher dimensions.

Perhaps the greatest advantage of RBF methods is that, in contrast to finite

elements and finite differences, they offer mesh free approximation. Highly important

is also the ease in which these methods can be generalized to higher dimensions. We

only have to consider the Euclidean norm of the distance between a point and the

center of the RBF in order to find its value and therefore, the majority of times, the

same function can be used to solve problems in any dimension.

These two main characteristics of RBFs captured the attention of mathematicians.

Since the time Hardy’s MQ method was first introduced , several algorithms utilizing

different RBFs have been developed, each with its own merits and faults.

An ideal algorithm would combine ease of implementation with high accuracy

and efficiency. The aim of this thesis is the implementation and comparison, in terms

of accuracy and conditioning of the resulting linear system, of three different radial

basis function algorithms for solving convection-diffusion equations in one and two

dimensions. The methods we consider are collocation [8],[9], a Galerkin formulation

method [1],[3],[11],[21] and generalized interpolation [4]. We will implement each of

these methods using two different types of RBFs, an infinitely differentiable one and

two compactly supported functions.

1.2 Radial Basis Functions

As mentioned in the previous section, throughout this project we will make use of

different RBFs when implementing our methods. We consider the infinitely differen-

tiable Gaussian function and two of Wendland’s [19] compactly supported functions

for one and two dimensions. These functions are available in Table 1.1.

Type of RBF φ(r) r ≥ 0 Ck

Gaussian exp(−r2

) C∞

Wendland (1D) (1 − r)5

+(8r2

+ 5r + 1) C4

Wendland (2D) (1 − r)6

+(35r2

+ 18r + 3) C4

Table 1.1: Table of radial basis functions.

We take as the input r for our RBF the Euclidean distance of a point from the

centre of the function, scaled by a scaling parameter δ ∈ R, that is,

r =

x − xj

δ

, j = 1, .., n. (1.3)

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-14-320.jpg)

![(a) Gaussian (b) Wendland (1D)

(c) Wendland (2D)

Figure 1.2: Radial basis functions, with centre xj = 4

9

, for different values of δ.

The parameter δ affects the shape of the RBF, as well as the accuracy of the method.

Observing Figure 1.2 we can see that as we increase the scaling parameter δ the

Gaussian RBF flattens out while the support radius of the two Wendland functions

increases. We expect that increasing δ will result in larger condition numbers for our

systems, especially for the Gaussian function which is not compactly supported.

A slight advantage of the Gaussian RBF is the fact that it can be used for ap-

proximations in any dimension, while we need to use a different compactly supported

Wendland function for each dimension. The reason why the same Wendland function

should not be used for any dimension has to do with the positive definiteness of com-

pactly supported functions, such as the Wendland RBFs, being dependent on how

many dimensions we are working with, as stated in [19]. A positive definite function

results in a positive definite linear system for (1.2), which in turns implies that we

can always find a unique solution, as all its eigenvalues are positive.

1.3 Model Problems

In this section we give the model problems on which we will test the different RBF

algorithms. Our 1D convection diffusion equation with Dirichlet boundary conditions

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-15-320.jpg)

![(a) = 0.01 (b) = 0.5

Figure 1.3: Exact solutions for one dimensional model problem.

is given by

− u + u = 0, 0 < x < 1,

u(0) = 1,

u(1) = 0,

(1.4)

where > 0 is the diffusion coefficient. The exact solution for this problem is

u(x) =

1 − exp(−(1 − x)/ )

1 − exp(−1/ )

. (1.5)

We will also consider a two dimensional problem, again with Dirichlet boundary

conditions. It is given by

− 2

u + (1, 2) · u = 0, (x, y) ∈ Ω,

u(1, y) = 0, y ∈ [0, 1]

u(x, 1) = 0, x ∈ [0, 1]

u(0, y) =

1 − exp(−2(1 − y)/ )

1 − exp(−2/ )

, y ∈ [0, 1],

u(x, 0) =

1 − exp(−(1 − x)/ )

1 − exp(−1/ )

, x ∈ [0, 1],

(1.6)

where again > 0 is the diffusion coefficient and Ω = (0, 1)2

. The exact solution of

the problem is

u(x, y) =

1 − exp(−(1 − x)/ )

1 − exp(−1/ )

1 − exp(−2(1 − y)/ )

1 − exp(−2/ )

. (1.7)

In both cases, varying affects how stiff the solution is and hence how easy it is to

construct an approximation for it, i.e., for small values of our solution becomes stiff

whereas for values close to 1 we have a solution whose gradient is not as steep. We

will perform our numerical experiments for two values of , namely = 0.01 for which

our solutions are stiff and = 0.5 for which the solutions are more well behaved, see

Figures 1.3 and 1.4.

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-16-320.jpg)

![Chapter 2

Collocation

2.1 Method Description

Collocation, which was first introduced by Kansa [8], [9], is perhaps the most straight-

forward method amongst the three to be discussed. In order to demonstrate how collo-

cation works, let us first consider the following general convection-diffusion equation,

Lu = − 2

u + b · u + cu = f in Ω ⊆ Rd

u = gD on ∂Ω

(2.1)

where > 0 is the diffusion coefficient and b ∈ Rd

.

The first step of this method is to consider a set of basis functions

Φj(x) = φ

x − xj 2

δ

, j = 1, ..., N, (2.2)

where N is the total number of points we are using and j indicates which node

we are centering around. Note that we are using Φj as a function with a vector

argument and φ as a function with a scalar argument. The set of points used are

known as collocation points. We then form our approximate solution by taking a

linear combination of our basis functions, that is,

s(x) =

N

j=1

CjΦj(x). (2.3)

Substituting s(x) back into our equation and boundary conditions and evaluating at

each of our N points gives,

N

j=1

Cj (− 2

Φj(xi) + b · Φj(xi) + cΦj(xi)) = f(xi) i = 1, ..., N∗

,

N

j=1

Cj Φj(xi) = gD(xi) i = N∗

+ 1, ..., N,

(2.4)

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-19-320.jpg)

![where points 1 to N∗

are located within the domain and points N∗

+1 to N lie on the

boundary. We will only consider uniform distributions for all methods in this project,

for comparison purposes. The system of equations (2.4) can be written as a matrix

equation of the form

AC = F (2.5)

where

A =

Lφ

φ

, C =

C

, F =

f

gD

. (2.6)

The matrix A has dimensions N × N and F, C are N dimensional vectors. The

method is also known as unsymmetric collocation [7] because of the non symmetric

collocation matrix A. Note that the matrix A is not symmetric even if the PDE is

self-adjoint. In order to acquire the unknown coefficients Cj we must solve Equation

(2.5) for C. It is therefore important that the collocation matrix is nonsingular for

this method to work.

In the case of a simple interpolation problem, see (1.2), this method may some-

times yield singular collocation matrices for specific RBFs [7], like Thin Plate Splines

for which φ(r) = r2

log(r). This can be fixed by adding an extra polynomial to (2.3)

and imposing additional constraints on the coefficients Cj in order to eliminate the

additional degrees of freedom. However, it has been proven that this is not the case

for elliptic problems. Hon and Schaback [7] have managed to construct examples

where the collocation matrix becomes singular, whether you add the extra appropri-

ate polynomial or not.

In particular, Hon and Schaback [7], have managed to find, relatively easily, cases

where using the Gaussian RBF results in a singular collocation matrix. Numerical

experiments were performed with Wendland functions as well but a singular colloca-

tion matrix was not found. However, Hon and Schaback do not believe that using the

compactly supported Wendland functions will always result in a nonsingular system

of equations. This indicates however that we should probably expect better condi-

tioning when using the Wendland RBFs, compared to the Gaussian. We also note

that we will not be considering any additional polynomial terms in our approximate

solution because, as stated by [10] and [2], they do not offer any significant benefits

with regards to the accuracy of the method.

In the following sections of this chapter we will apply the method to our model

problems in one and two dimensions, for different values of , using the Wendland

and Gaussian RBFs. The aim is to look into which of the two RBFs perform better

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-20-320.jpg)

![Gaussian Wendland (1D) Wendland (2D)

φ(r) exp(−r2

) (1 − r)5

+(8r2

+ 5r + 1) (1 − r)6

+(35r2

+ 18r + 3)

φ (r) −2r exp(−r2

) (1 − r)4

+(−56r − 14r) (1 − r)5

+(−280r2

− 56r)

φ (r) (−2 + 4r2

) exp(−r2

) (1 − r)3

+(336r2

− 42r − 14) (1 − r)4

+(1960r2

− 224r − 56)

Table 2.1: Derivatives of RBFs.

in terms of conditioning of the collocation matrix and accuracy of the solution. Also

of interest is how the value of the scaling parameter δ affects the method.

2.2 One Dimension

Having explained how the collocation method works, we will now apply it to our 1D

problem (1.4). Prior to coding the method in MATLAB, we must first calculate the

first and second derivatives of φ with respect to x, that is

dΦj

dx

=

1

δ

dφ

dr

if x > xj

−1

δ

dφ

dr

if x < xj

,

d2

Φj

dx2

=

1

δ2

d2

φ

dr2

, (2.7)

where the derivatives of φ with respect to r can be found in Table 2.1. The translation

of the collocation method to a computer program is relatively simple, which is one of

the reasons why this method became popular.

2.2.1 Scaling Parameter δ

The scaling parameter δ is known to affect the accuracy of RBF based methods.

Figures 2.1 and 2.2 show how the error and condition number get affected when we

vary δ, for the Wendland(1D) and Gaussian RBFs respectively, where = 0.01. The

Wendland(1D) RBF seems to provide us with exponential convergence as we increase

δ. However as the error decreases the condition number of the method increases. This

implies that as we increase δ the method becomes unstable due to the ill-conditioning

of the collocation matrix. Something similar was also observed for plain interpolation

problems, where as mentioned in Schaback [15],‘either one goes for a small error and

gets a bad sensitivity, or one wants a stable algorithm and has to take a comparably

larger error’. As far as the Wendland(1D) case of the method is concerned, for

= 0.01, we observe that after some point increasing δ any further does not have a

significant impact on the accuracy while it still affects the condition number. This

suggests that it might be worth sacrificing a bit of accuracy for a more stable method.

Changing the number of points does not affect the behaviour observed in Figure 2.1.

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-21-320.jpg)

![Chapter 3

Galerkin Formulation

3.1 Galerkin Method for Robin Problems

The second method we consider is based on a Galerkin formulation of the problem.

It is somewhat similar to a finite element method with the distinct difference that we

do not need to perform a computationally expensive mesh generation. Of course the

basis functions used in our case are radially symmetric.

Wendland [21], looked into a Galerkin based RBF method for second order PDEs

with Robin boundary conditions, for an open bounded domain Ω having a C1

bound-

ary, that is,

−

d

i,j=1

∂

∂xi

aij

∂u

∂xj

(x) + c(x)u(x) = f(x), x ∈ Ω,

d

i,j=1

aij(x)

∂u(x)

∂xj

νi(x) + h(x)u(x) = g(x), x ∈ ∂Ω,

(3.1)

where aij, c ∈ L∞(Ω), i, j = 1, ..., n, f ∈ L2(Ω), aij, h ∈ L∞(∂Ω), g ∈ L2(∂Ω) and

ν is the outward unit normal vector to ∂Ω. The entries aij(x) satisfy the following

ellipticity condition, namely, there exists a constant γ > 0 such that for all x ∈ Ω

and all α ∈ Rd

γ

d

j=1

α2

j ≤

d

i,j=1

aij(x)αiαj. (3.2)

As stated in [21], under the additional assumption that the functions c and h are

both non-negative and one or both of them are ‘uniformly bounded away from zero

on a subset of nonzero measure of Ω for c or ∂Ω for h, we obtain a strictly coercive

and continuous bilinear functional’

a(u, v) =

Ω

d

i,j=1

aij

∂u

∂xj

∂v

∂xi

+ cuv dx +

∂Ω

huv dS ∈ V × V, (3.3)

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-30-320.jpg)

![where V = H1

(Ω). Combining a(u, v) with the continuous linear functional l(v) ∈ V ,

where

l(v) =

Ω

fvdx +

∂Ω

gvdS, (3.4)

we obtain the weak formulation of the problem,

find u ∈ V such that a(u, v) = l(v) holds for all v ∈ V, (3.5)

which by the Lax-Milgram theorem is always uniquely solvable.

The next step is to consider a finite dimensional subspace VN ⊂ V spanned by

our RBFs, that is,

VN := span{Φj(x), j = 1, ..., N} (3.6)

for a set of pairwise distinct points X = {x1, ..., xN} ∈ Ω, and search for an approx-

imation s ∈ VN to u that satisfies a(s, v) = l(v) for all v ∈ VN . It is mentioned in

[21] that is preferable to use compactly supported functions, such as the Wendland

RBFs, in order to obtain some sparsity in the resulting matrix. Wendland provided

the theoretical bounds for such settings. We give below a special case of Theorem

5.3, with m = 0, proved in [21].

Theorem 3.1.1.

Assume u ∈ Hk

(Ω) and Φ is such that its Fourier transform satisfies ˆΦ(ω) ∼ (1 +

ω 2)−2σ

with σ ≥ k > d/2. Then there exists a function s ∈ VN , such that

u − s L2(Ω) ≤ Cˆhk

u Hk(Ω),

for sufficiently small ˆh = supx∈Ω min1≤j≤N x − xj 2.

The Wendland RBFs satisfy the requirements of the theorem with σ = 3 and

σ = 3.5, for the 1D and 2D versions respectively. Also, ˆh corresponds to the data

density or mesh norm as stated in [4] that ‘measures the radius of the largest data-free

hole contained in Ω’.

3.2 Galerkin Method for the Dirichlet Problem

In our case, both model problems have Dirichlet boundary conditions. This poses a

difficulty for Galerkin methods as they cannot simply be used with RBFs, as men-

tioned in [1]. As the boundary conditions need to be satisfied by the space in which

the solution u belongs [1], [3], a problem arises because RBFs, even compactly sup-

ported ones, do not satisfy these boundary conditions in general. Therefore the error

bound given in Theorem 3.1.1, is most likely, not valid in our case.

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-31-320.jpg)

![Different methods have been developed to tackle problems with Dirichlet boundary

conditions, including approximating the Dirichlet problem by an appropriate Robin

problem [1], using a Lagrange multiplier approach [3] and others [11]. We will follow a

quite different approach by adding additional terms to our weak formulation in order

to impose the boundary conditions.

The weak formulation of the general convection-diffusion problem (2.1) is to find

u ∈ H1

E(Ω) such that

Ω

u · v + b · uv + cuv dΩ −

∂Ω

v

∂u

∂ν

dS =

Ω

fv dΩ (3.7)

for all v ∈ H1

E0

(Ω), where H1

E(Ω) = {ω| ω ∈ H1

(Ω), ω = gD on ∂Ω} and H1

Eo

(Ω) =

{ω| ω ∈ H1

(Ω), ω = 0 on ∂Ω}. Note here that the boundary terms vanish since

v ∈ H1

Eo

(Ω). However, as we have pointed out earlier our RBFs span VN which is a

subspace of H1

(Ω) and therefore cannot be used in this setting. In order to impose

the boundary conditions we consider the following relation

∂Ω

θ

∂v

∂ν

+ κv u dS =

∂Ω

θ

∂v

∂ν

+ κv gD dS, (3.8)

where θ ∈ [−1, 1] and κ = c/h, which we incorporate in (3.7). Note that here h

is the meshsize, which is constant as we are using a uniform distribution. Our new

formulation of the problem is,

find u ∈ H1

(Ω) such that a(u, v) = l(v) holds for all v ∈ H1

(Ω), (3.9)

where

a(u, v) =

Ω

u · v + b · uv + cuv dΩ −

∂Ω

v

∂u

∂ν

dS

+

∂Ω

θ

∂v

∂ν

+ κv u dS

l(v) =

Ω

fv dΩ +

∂Ω

θ

∂v

∂ν

+ κv gD dS.

(3.10)

The idea of imposing the boundary conditions in a weak sense, like we have done

here, has been discussed in [16] for finite element methods. After a few numerical

experiments we have found that choosing θ = −1 and κ = 5/h produces more accurate

results the majority of time. Setting θ = −1 means that the symmetric part of the

elliptic operator will correspond to a symmetric bilinear form.

We construct the approximate solution s ∈ VN by taking a linear combination of

our basis functions, that is,

s(x) =

N

j=1

CjΦj(x) (3.11)

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-32-320.jpg)

![(a) Wendland(1D) with δ = 0.2. (b) Gaussian with δ = 0.25.

Figure 3.5: Log of L2 norm of the error versus N for = 0.01.

is used, the choice of δ is not as tricky as when = 0.01. Now for the Gaussian,

even though the choice of δ is a bit more difficult, see Figure 3.4, the accuracy of the

method is clearly better, even though more unstable, for most values of N, see Tables

B.3 and B.4.

3.3.2 Increasing the number of points N

It should be possible to achieve convergence of the method by increasing the number

of points used. We remind the reader that we are always using uniformly distributed

points. As can be observed from the tables in Appendix B, values of δ that work well

with a specific number of points, do not necessarily result in an accurate scheme if

we change N. This is an issue if one wishes to obtain convergence by increasing the

number of points used. After a few numerical experiments we realise that keeping δ

fixed while increasing N does not guarantee convergence for either RBF, see Figure

3.5. Also, for compactly supported functions, such as the Wendland(1D) RBF, using

an increasingly smaller stepsize h while keeping the support fixed, eliminates the

advantage of having sparse matrices [20]. The fact that we cannot obtain convergence

by increasing N confirms that Theorem 3.1.1 does not hold in our setting.

The other choice we have would be to take δ to be proportional to h. This choice

would potentially keep the sparsity of the resulting linear systems if a compactly

supported function is used. However numerical experiments suggest that convergence

is unattainable in this setting too. This was also observed in [20] where the Helmholtz

equation is considered.

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-36-320.jpg)

![Chapter 4

Generalised Interpolation

The final method we will discuss is called generalised interpolation. This method is

unique in the sense that it results in symmetric collocation matrices which are also

positive definite for constant coefficient PDEs when positive definite RBFs are used

[22].

Wendland in [22] has managed to provide bounds for the smallest eigenvalue of this

method for general boundary value problems, while in [4] a bound on the condition

number is provided for strictly elliptic PDEs with Dirichlet boundary conditions, i.e.,

for

Lu =f in Ω,

u =gD on ∂Ω,

(4.1)

where

Lu(x) =

d

i,j=1

aij(x)

∂2

∂xi∂xj

u(x) +

d

i=1

bi(x)

∂

∂xi

u(x) + c(x)u(x), (4.2)

and the coefficients aij(x) satisfy the ellipticity condition (3.2). These results however

hold only for a specific type of RBFs. As the setting discussed in [4] is closer to our

model problems we will focus on it.

4.1 Method Description

Before moving on to the convergence and stability results , in this section, we provide

the reader with a description of the method. To start off, we define the functionals

λi as follows

λi(u) = Lu(xi) if xi ∈ Ω,

λi(u) = u(xi) if xi ∈ ∂Ω.

(4.3)

For generalised interpolation, we construct our approximation s to the solution u in

a slightly different way than the previous two methods. The approximation s to the

31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-42-320.jpg)

![exact solution u, this time is given by

s(x) =

N

j=1

Cjλχ

j φ

x − χ 2

δ

, (4.4)

where this time our RBF depends on two variables x and χ. Note that we have

applied the functional λj to the function φ with respect to the new argument χ. In

this chapter we redefine Φ as a function of two vector arguments, that is,

Φ(x, χ) = φ(r),

where r = x−χ 2

δ

. As always, we are using N uniformly distributed points in order

to simplify the comparison process. We then substitute our expression for s(x) back

into the PDE and boundary conditions or equivalently apply the functional λi to s

with respect to x, that is,

λx

i (s) = fi, i = 1, ..., N, (4.5)

where

fi = f(xi) if xi ∈ Ω,

fi = gD(xi) if xi ∈ ∂Ω.

(4.6)

This can be rewritten as a matrix equation

AC = F, (4.7)

where the entries of the symmetric collocation matrix A are given by

Ai,j = λx

i λχ

j φ

x − χ 2

δ

, (4.8)

and the entries of the right-hand-side vector F are given by Fi = fi. Solving the

matrix Equation (4.7) will provide us with the unknown coefficients Cj and hence the

approximate solution s(x).

4.2 Stability and Accuracy

We first need to give the definition of the fractional Sobolev space Wσ

2 (Rd

). As stated

in [4] ‘we describe functions in the fractional Sobolev space Wσ

2 (Rd

) as those square

integrable functions that are finite in the norm

f 2

Wσ

2 (Rd) =

Rd

| ˆf(ω)|2

(1 + ω 2

2)σ

dω, (4.9)

where ˆf is the usual Fourier transform’. We note here that σ can be both an integer

and a fraction. Also needed is the definition of a reproducing kernel to a Hilbert

space, which is given below as found in [4].

32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-43-320.jpg)

![Definition 4.2.1. (Reproducing Kernel)

Suppose H ⊂ C(Ω) denotes a real Hilbert space of continuous functions f : Ω → R;

then Φ : Ω × Ω → R is said to be a reproducing kernel for H if

• Φ(·, χ) ∈ H for all χ ∈ Ω

• f(χ) = (f, Φ(·, χ))H for all f ∈ H and all χ ∈ Ω.

Both of our RBFs are reproducing kernels to a Hilbert space, also know as the

native space of the RBF [5]. We now move on to the main stability result proven

in [4]. It is important here to notice that the result only holds for the Wendland

RBFs which are compactly supported reproducing kernels. As we will also see from

numerical experiments in the following sections, this result does not apply to the

Gaussian RBF.

Theorem 4.2.1.

Suppose Wσ

2 (Rd

) with σ > d/2+2 has a compactly supported reproducing kernel, Φ,

which has a Fourier transform satisfying

c1(1 + ω 2

2)−σ

≤ ˆΦ(ω) ≤ c2(1 + ω 2

2)−σ

.

Let 0 < δ ≤ 1. Suppose L is a linear, strictly elliptic, bounded, second order differ-

ential operator. Then for sufficiently small δ the condition number of the collocation

matrix A can be bounded by

cond(A) ≤ Cδ−4

1 +

2δ

h

d

δ

h

2σ−d

with a constant C independent of h and δ.

The bound on the condition number of A is derived from the bounds

λmin ≥ C1

h

δ

2σ−d

,

λmax ≤ C2δ−4

1 +

2δ

h

d

,

(4.10)

where λmax and λmin are respectively the maximum and minimum eigenvalues of A

and C1, C2 > 0 are independent of h and δ. It is proved in [19], that Wendland(1D)

and Wendland(2D) RBFs satisfy the conditions of Theorem 4.2.1 with σ = 3 and

σ = 3.5 respectively.

Wendland and Farrell in [4] have also provided a bound on the L2 norm of the

error. We give below Lemma 4.4 which is stated and proven in [4].

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-44-320.jpg)

![Gaussian Wendland (1D) Wendland (2D)

φ (r) −4r(2r2

− 3)e−r2

(1 − r)2

+(−1680r2

+ 840r) (1 − r)3

+(5040r −

11760r2

)

φiv

(r) (12 − 48r2

+ 16r4

)e−r2

(1 − r)+(6720r2

− 5880r + 840) 1680(1 − r)2

+(5r −

3)(7r − 1)

Table 4.1: Derivatives of RBFs.

Theorem 4.2.2. (L2−error)

Assume δ ∈ (0, 1]. Let u ∈ Hσ

(Ω) be the solution of (4.1). Let the domain Ω have a

Ck,s

boundary for s ∈ (0, 1] such that σ = k + s and k := σ > 2 + d/2. Then the

error between the solution u and its generalised interpolation approximation s can be

bounded in the L2 norm by

u − s L2(Ω) ≤ Cδ−σ

hσ−2

u Hσ(Ω),

where h = supx∈Ω min1≤j≤N x − xj 2.

In the original version of the theorem, h is the maximum between the mesh norm

of the points in Ω and the mesh norm of the points on the boundary ∂Ω. In our case

we have uniformly distributed points so h can be taken to simply be the meshsize.

The definition of a Ck,s

boundary is given in [23], Definition 2.7.

In our numerical experiments we will consider three cases for δ, the stationary

setting δ = ch, the nonstationary setting δ = ch1−2/σ

and also keeping δ fixed. We

note that the nonstationary setting will only be considered for the Wendland RBFs.

4.3 One Dimension

Prior to coding the method for our 1D model problem in MATLAB, we need to

calculate the appropriate derivatives. Let Gj = λχ

j φ(|x−χ|

δ

) for j = 1, ..., N where

Gj(x) = −

∂2

Φ

∂χ2

+

∂Φ

∂χ χ=xj

, j = 2, ..., N − 1,

Gj(x) = φ

|x − xj|

δ

, j = 1, N,

(4.11)

and

∂Φ

∂χ

=

−1

δ

dφ

dr

if x > χ

1

δ

dφ

dr

if x < χ

,

∂2

Φ

∂χ2

=

1

δ2

d2

φ

dr2

. (4.12)

We can then write s(x) = N

j=1 CjGj(x) which we essentially substitute back into

the PDE and boundary conditions. We therefore need to calculate up to the fourth

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-45-320.jpg)

![(a) Gaussian with δ = 0.25. (b) Wendland(1D) with δ = 0.25.

Figure 4.7: Eigenvalue distributions for = 0.01.

and C.3. The Gaussian however, for up to a certain number of points yielded real

eigenvalues some of which were negative and extremely close to zero. Increasing N

further caused complex eigenvalues with very small imaginary parts to appear, see

Tables C.2 and C.4. This fact confirms that using the Wendland(1D) function pro-

duces a positive definite collocation matrix. However our numerical findings suggest

this is not the case if we use the Gaussian RBF, see Figure 4.7. Since the colloca-

tion matrix A is always symmetric this implies that the eigenvalues should always

be real. Therefore the imaginary parts must be due to rounding errors either in the

computation of the matrix entries or in the computation of the eigenvalues. In fact

the matrix A should be positive definite [4], so the negative eigenvalues must also be

an artifact. Nevertheless, the smallest Gaussian eigenvalues are significantly smaller

than the smallest Wendland ones.

Now, as far as the bounds given by (4.10) are concerned we found that they

were satisfied when the Wendland(1D) was used, for all the different values of N we

considered and δ ∈ (0, 1], for both values of . Of course there is no reason to check

these bounds for the Gaussian as they only apply to compactly supported RBFs.

4.4 Two Dimensions

Generalised interpolation requires us to calculate up to the fourth derivative of our

RBFs, therefore it can only be used with RBFs that at least belong in C4

. Another

drawback that becomes obvious when the method is used for higher dimensions, is the

need to basically apply the PDE twice, which complicates the process significantly

even in just two dimensions.

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-50-320.jpg)

![(a) Gaussian with δ = 10h.

(b) Wendland(2D) with

δ = 10h1−2σ.

Figure 4.10: Log of the error versus N for = 0.5.

could only be obtained for = 0.01 if the compactly supported Wendland(2D) RBF

was used with a fixed δ or with δ = ch1−2/σ

, where σ = 3.5. As before, increasing c

seems to help us achieve better accuracy. Once more, our findings agree with Theorem

4.2.2.

In our numerical experiments for = 0.5, however, we found that the Gaussian

could produce a convergent scheme for δ = ch, providing us with better accuracy than

the Wendland(2D) RBF, see Figure 4.10. Of course this increased accuracy that the

Gaussian RBF provides us with goes together with an enormous condition number.

4.4.3 Eigenvalues

Experimenting with various values for N we see that as for the 1D case using the

Wendland(2D) produces a collocation matrix with only real and positive eigenvalues

for both = 0.01 and = 0.5. Furthermore, we found that these eigenvalues satisfied

the bounds given by (4.10) for δ ∈ (0, 1].

Now if we use the Gaussian RBF, in contrast to the 1D case, we only found real

eigenvalues in all our numerical experiments. However the majority of times some of

them were negative, even though with a very small modulus. The largest in modulus

negative eigenvalue in Figure 4.11(a) is −1.74×10−13

. Now, since the matrix is again

theoretically positive definite, we believe that the negative eigenvalues appear due to

rounding errors, as for the 1D model problem. This confirms, however, that similar

bounds to (4.10) cannot be obtained when we use translates of the Gaussian RBF as

our basis functions, as we had also deduced for the 1D case.

42](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-53-320.jpg)

![thing that can be added to the list of disadvantages of this method, is the difficulty

of applying it to problems with Dirichlet boundary conditions.

Now in terms of accuracy, we have seen that collocation performs better than gen-

eralised interpolation in all cases, when the Wendland RBFs are used. The opposite

is true when we make use of the Gaussian RBF, providing better accuracy at the cost

of instability.

The choice therefore seems to depend on what one regards as more important,

stability or accuracy. If the highest accuracy is required, then the Gaussian RBF

should be chosen and since all methods are more or less unstable for this choice of

RBF, we might as well choose the one that gives the most accurate solution, i.e.,

generalised interpolation. However we note here that for the stiff version of the

2D model problem, collocation was the only method that could produce acceptable

accuracy for both RBFs.

Now, if one is willing to sacrifice a bit of accuracy in order to have stability and

therefore make the choice of δ easier, the Wendland RBFs should be chosen. The

most accurate method when the Wendland RBFs are used is collocation.

Concluding, our personal choice would be the collocation method used with the

Wendland RBFs, especially for stiff problems. It is the most efficient and easy to

implement out of the three and also provides us with convergence as we increase the

number of points. Its only drawbacks is that the collocation matrix A might not

always be invertible, however as mentioned in [7] these cases are rare. Also, the lack

of theory for collocation, as opposed to the other two approaches, might also be seen

as a disadvantage, even though in the case of the Galerkin method the theory is not

really applicable.

49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-60-320.jpg)

![Chapter 6

Further Work

6.1 Extension: Choice of the Scaling Parameter

We have observed throughout this project that the choice of the scaling parameter

plays an important role in the accuracy of all three methods. We were able to find

the optimal values of δ because the exact solution to our model problems was known.

However this will not be the case when the algorithms are used in practice. It would

therefore be very useful if there was a way to predict which value of δ should be used.

Mongillo in [13] investigates the use of ‘predictor functions’ whose behaviour is similar

to that of the interpolation error, in the case of collocation used for plain interpolation

problems. The optimal parameter δ is chosen by minimizing these predictor functions.

Uddin in [18] has tried one of these ‘predictor functions’, more specifically the

‘Leave One Out Cross Validation’ (LOOCV), in the context of Collocation applied to

time-dependent PDEs. As also mentioned in [13], for LOOCV we use N − 1 points,

out of the total of N points, in order to compute the solution. We then test the error

at the point we have left out. That is we have,

LOOCV (δ) =

N

i=1

|si(xi) − fi|2

, (6.1)

where si is the approximate solution evaluated at N − 1 points by leaving out the

ith

point and fi is the exact value at points xi. This is repeated N times leaving

out a different point every time. As one might imagine, this procedure increases

the computational complexity of the algorithm, as we have to solve N systems of

equations. This drawback can be eliminated using Rippas algorithm, [14] through [13],

which is also the version of LOOCV algorithm used in [18]. What Rippa essentially

showed was that it is not necessary to solve N linear systems as we have,

si(xi) − fi =

Ci

A−1

ii

. (6.2)

50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-61-320.jpg)

![(a) Gaussian. (b) Wendland(1D).

Figure 6.1: Log of exact and predicted errors versus δ with N = 64 and = 0.01.

RBF method used is Collocation.

As stated in [13], using Rippas algorithm reduces the computational complexity to

O(N3

) rather than O(N4

), which is the complexity for solving a dense linear system

of equations.

Uddin’s numerical experiments have shown that Rippa’s algorithm is not very

useful when used for time-dependent PDEs. Even though in some cases the results

were fairly good, in general the numerical experiments have shown that it does not

always predict good values for δ. Nevertheless, looking into how well this algorithm,

and more generally ‘predictor functions’, perform for the methods we have used in

this project is a topic that requires further work and study.

Here, we have implemented Rippa’s algorithm for all three methods using both

RBFs. Detailed results can be found in Appendix E for the 1D model problem.

Figure 6.1 shows the behaviour of the exact error and the error predictor function

obtained through LOOCV. We can see that the predictor function mimics the error

behaviour best when the Gaussian RBF is used. However our numerical experiments

seem to agree with Uddin’s findings for time-dependent PDES, i.e., even though in

some cases this algorithm gives good results, see Table E.3, in general it is not a

very reliable way to predict δ. As already mentioned in this section, further work in

finding trustworthy methods for predicting δ is required.

6.2 Extension: Point Distribution

Another interesting extension to this project would be to investigate how the methods

perform when non uniform distributions are used. We have seen that a uniform

distribution is perfectly adequate when the solution to be approximated is smooth,

i.e., in our case for = 0.5. However, for stiff problems like for = 0.01, we saw that

51](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-62-320.jpg)

![a much greater number of points was required in order to obtain acceptable levels of

accuracy. This fact provides the motivation to look into other type of meshes.

In this section, we will briefly look at the Shishkin mesh [17] and how it affects

the accuracy of the methods when applied to our 1D model problem. A Shishkin

mesh requires an odd number of points N, or equivalently an even number of mesh

spacings M = N − 1. Then, for an equation of the form

− u + bu = 0,

with constant b > 0, a Shishkin mesh consists of M/2 equal mesh spacings in the

interval [0, 1 − σ] and M/2 equal mesh spacings in the interval [1 − σ, 1], where

σ = min(1/2, 2 log(N)/b). (6.3)

For our model problem we have b = 1. We note here that when σ = 0.5 then the

Shishkin mesh reduces to a uniform distribution of the points, see Figure 6.2. This

is the case when = 0.5, therefore we will consider the case for = 0.01. A question

that naturally arises at this point is whether the value of δ should be the same for all

our basis functions. In order to answer this question we will perform our experiments

trying out different values of δ in each of the two differently scaled sections of the

interval [0, 1].

Carrying out our numerical experiments requires us to adjust our code in order to

admit two values for the scaling parameter δ instead of one, i.e., we now have δ = δ1

in the first part of the interval and δ = δ2 in the second part. We then repeatedly

solved our model problem each time using different combinations for our δ values,

for both RBFs and all three methods. We then picked out, for each method and

(a) Shiskin mesh for = 0.5 is just a

uniform distribution.

(b) Shishkin mesh for = 0.01 splits

the interval in two.

Figure 6.2: Shishkin mesh for = 0.01 and = 0.5 using N = 27 points.

52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-63-320.jpg)

![RBF, the two δ values, amongst those considered, for which the approximate solution

displayed the lowest error. Detailed results form these experiments can be found in

Appendix E, Section E.2.

We found that using the Shishkin mesh in almost all cases considerably reduces

the error. Exceptions are for the collocation method with both RBFs and generalised

interpolation for the Gaussian, where for N = 9 and N = 27 the error actually

increases. However we feel that this might be avoided if we consider more δ values

from the same interval. We observe that for the Galerkin formulation method, using

the Shishkin mesh leads to reductions in the error as great as 99%, for example for the

Gaussian RBF for N = 27 which is the smaller error produced by any combination

of method and RBF for this many points. The most accurate solution, however, is

produced by collocation using the Wendland(1D) RBF for N = 243. It is also worth

noting that in most cases we have δ2 < δ1. Moreover, we observe that in general

the Shishkin mesh with the two different values for δ produces more ill-conditioned

systems than a uniform distribution does.

It is clear that a non uniform distribution of points might be beneficial for stiff

problems, however it does complicates RBF methods especially with respect to how

δ should be chosen. It would be interesting to look into how different distributions

affect the accuracy and also the stability of each of the methods, and whether some

of those methods work better for particular meshes. Without any doubt, alternative

meshes and specifically the Shishkin mesh are worthy of further research.

6.3 Extension: Multilevel Algorithms

Finally, a possible extension would be to look into how well the multilevel versions of

the three methods perform. In general, a multilevel algorithm consists of solving the

same problem on each level and only changing the right hand side. As mentioned in

[20], ‘on each level the residual of the previous level is interpolated’.

The multilevel version of generalized interpolation is investigated in [4] as a way

to overcome the problem of ill-conditioning of the collocation matrix A. This version

of the method is known to converge for δ = ch1−2/σ

. A multilevel algorithm, based

on a Galerkin formulation method, has also been proposed for the solution of PDEs

with Neumann boundary conditions in [20]. In that paper, the multilevel algorithm

is investigated as a solution to the problem of obtaining a convergent scheme and at

the same time not eliminating the sparsity of the matrix A. The multilevel versions

have been investigated theoretically in [4] and [20].

53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-64-320.jpg)

![= 0.5 δ Error Predicted δ Error

Collocation 0.31 3.9171e-08 0.46 1.0208e-06

Galerkin 0.17 2.3076e-06 0.11 1.8138e-05

Gen. Interpolation 0.43 4.3992e-09 0.49 2.7605e-08

Table E.4: Results for the actual δ for which the error is minimised and for the

predicted δ with the corresponding error. RBF used is the Gaussian with N = 32 for

= 0.5.

E.2 Point Distribution

This section contains results from all three methods, for both RBFs, when used with

a Shishkin mesh to solve the 1D problem with = 0.01. Note that we have two

values of δ here, δ1 corresponds to the value of δ used in the interval [0, 1 − σ] and

δ2 is used in the interval (1 − σ, 1]. The U.Error column corresponds to the error of

the approximate solution when a uniform distribution of points is used, for the value

of δ which minimizes it. The column U.cond(A) shows the condition number of the

corresponding matrix.

E.2.1 Collocation

N δ1 δ2 Error cond(A) U.Error U.cond(A)

9 0.4 0.1 0.39562 8.38e+02 0.30291 1.91e+03

27 3.8 3.8 0.0017414 7.97e+10 0.029909 6.64e+08

81 3.7 3.7 3.0637e-05 1.15e+12 0.00295 5.44e+10

243 0.9 1.4 1.9548e-06 4.35e+14 0.00014385 1.78e+12

Table E.5: Results for Collocation using the Wendland(1D) RBF for = 0.01.

N δ1 δ2 Error cond(A) U.Error U.cond(A)

9 0.14 0.02 0.40512 2.39e+02 0.25087 30.0

27 0.62 0.02 0.039876 3.61e+17 0.029754 6.49e+17

81 0.26 0.04 4.8402e-05 2.96e+18 0.00027538 4.58e+17

243 0.12 0.02 4.9847e-06 2.04e+19 5.9445e-06 1.86e+18

Table E.6: Results for Collocation using the Gaussian RBF for = 0.01.

75](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-86-320.jpg)

![Appendix F

MATLAB code

F.1 Collocation

F.1.1 Coll 1D.m

1 function [ X,A, Us ] = Coll 1D ( epsilon , N, choice , delta )

2 % Calculates the s o l u t i o n to the ODE

3 % −e p s i l o n ∗u’ ’+u’=0 , e p s i l o n > 0 , f o r 0<x<1,

4 % with boundary conditions u (0) =1, u (1) =0.

5 % Method : Collocation

6 % Radial b a s i s function of the form p h i j = Phi ( r )

7 % where r =|x−x j |/ delta .

8 % Artemis Nika 2014

9

10 %% D i s c r e t i z a t i o n in x−d i r e c t i o n :

11

12 % Equispaced points

13 x=l i n s p a c e (0 ,1 ,N) ;

14

15 %% Radial b a s i s function and d e r i v a t i v e s ( wrt to r )

16

17 i f choice==1

18 % t h i s r a d i a l b a s i s function has compact support f o r O<r <1.

19 Phi= @( r ) h e a v i s i d e (1−r ) ∗ (1−r ) ˆ5 ∗(8∗ r ˆ2 + 5∗ r + 1) ;

20 % h e a v i s i d e (0) =0.5 but here i t i s not a problem as f o r r=1

21 % the r e s t of Phi i s 0.

22 dPhi= @( r ) h e a v i s i d e (1−r ) ∗ (1−r ) ˆ4 ∗ (−56∗ r ˆ2 − 14∗ r ) ; % 1 st deriv .

23 ddPhi= @( r ) h e a v i s i d e (1−r ) ∗ (1−r ) ˆ3 ∗ (336∗ r ˆ2 − 42∗ r − 14) ; % 2nd der .

24 e l s e i f choice==2

25 % no compact support

26 Phi=@( r ) exp(−r ˆ2) ;

27 dPhi=@( r ) −2∗r ∗exp(−r ˆ2) ;

28 ddPhi=@( r ) (−2+4∗r ˆ2) ∗ exp(−r ˆ2) ;

29 e l s e

30 e r r o r ( ’ Choice of r a d i a l b a s i s not c o r r e c t . Choices : 1 = compact support , 2 = no

compact support ’ )

31

32 end

33

34

35 %% Create Matrix Equation

36 A=zeros (N,N) ;

37 % f o r 0<x<1

38 f o r i =2:N−1

39 f o r j =1:N

40 r=abs (x ( i )−x ( j ) ) / delta ; % x j −> p h i j ( x i )

41 % f i r s t d e r i v a t i v e of p h i j a l t e r n a t e s sign because of the abs value

77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-88-320.jpg)

![42 i f x( i ) > x ( j )

43 dphi= (1/ delta ) ∗ dPhi ( r ) ;

44 e l s e

45 dphi= − (1/ delta ) ∗ dPhi ( r ) ;

46 end

47 ddphi= (1/ delta ˆ2) ∗ ddPhi ( r ) ;

48 % Calculate e n t r i e s of matrix

49 A( i , j )= − e p s i l o n ∗ ddphi + dphi ;

50 end

51 end

52

53 % F i r s t and l a s t rows of matrix A − boundary conditions

54 f o r j =1:N

55 % f o r x i=0=x 1 ;

56 A(1 , j )= Phi ( abs(0−x ( j ) ) / delta ) ; %x 1=0 −> p h i j (0)

57 % f o r x i=1=x N ;

58 A(N, j )= Phi ( abs(1−x ( j ) ) / delta ) ;

59 end

60

61 % RHS of Matrix Equation

62 b= zeros (N, 1 ) ;

63 b (1)= 1; % because of u (0)=1

64

65 %% Solve Matrix Equation to obtain c o e f f i c i e n t vector U

66 c=Ab ;

67

68 %% Add up c o e f f i c i e n t s to obtain s o l u t i o n vector Us

69 Nsol =100;

70 Us=zeros ( Nsol , 1 ) ;

71 X=l i n s p a c e (0 ,1 , Nsol ) ;

72

73 f o r i =1: Nsol

74 dummy=0;

75 f o r j =1:N

76 dummy=dummy+c ( j ) ∗Phi ( abs (X( i )−x ( j ) ) / delta ) ;

77 end

78 Us( i )=dummy;

79 end

80

81

82 %% Exact Solution

83

84 uExact= (1− exp ((X−1)/ e p s i l o n ) ) /(1−exp(−1/ e p s i l o n ) ) ;

85

86

87 %% Error

88 Error=zeros ( Nsol , 1 ) ;

89 f o r i =1: Nsol

90 Error ( i )=abs (Us( i )−uExact ( i ) ) ;

91 end

92

93 % %% Plots

94 f i g u r e (1)

95

96 subplot (2 ,1 ,1)

97

98 plot (X, Us , ’ r ’ , ’ LineWidth ’ ,2) ;

99 axis ( [ 0 , 1 , 0 , 1 . 5 ] ) ;

100 s t r=s p r i n t f ( ’ e p s i l o n= %f , delta= %f , h= %f ’ , epsilon , delta , h) ;

101 t i t l e ( s t r ) ;

102 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’ Numerical Solution ’ ) ;

103

104 subplot (2 ,1 ,2)

105 plot (X, Error , ’k−∗ ’ )

106 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’ Error ’ ) ;

107

108 f i g u r e (2)

109

78](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-89-320.jpg)

![110 hold on

111 plot (X, Us , ’ r−∗ ’ , ’ LineWidth ’ ,2) ;

112 plot (X, uExact , ’ LineWidth ’ ,2) ;

113 axis ( [ 0 , 1 , 0 , 1 . 5 ] ) ;

114 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’u ’ ) ;

115 legend ( ’ Numerical Solution ’ , ’ Exact Solution ’ )

116 t i t l e ( s t r ) ;

117 hold o f f

118

119

120

121 end

F.1.2 Coll 2D.m

1 function [ xsol , ysol ,A,U]= Coll 2D ( epsilon , N1, N2, delta , choice )

2 % Calculates the s o l u t i o n to the PDE

3 % −e p s i l o n ∗( u xx + u yy ) + (1 ,2) ∗grad (u) =0, (x , y ) in (0 ,1) ˆ2 ,

4 % with boundary conditions

5 % u (1 , y )=u(x , 1 )=0

6 % u (0 , y )=(1−exp(−2∗(1−y ) / e p s i l o n ) ) /(1−exp(−2/ e p s i l o n ) )

7 % u(x , 0 ) =(1−exp(−2∗(1−x ) / e p s i l o n ) ) /(1−exp(−1/ e p s i l o n ) ) .

8 % Method : Collocation

9 % Radial b a s i s function of the form p h i j = Phi ( r )

10 % where r =|x−x j |/ delta .

11 % Artemis Nika 2014

12

13 %% D i s c r e t i z a t i o n in x and y d i r e c t i o n

14 x=l i n s p a c e (0 ,1 ,N1) ;

15 y=l i n s p a c e (0 ,1 ,N2) ;

16 N=N1∗N2 ; % t o t a l number of nodes

17

18 %% Radial b a s i s function and d e r i v a t i v e s ( wrt to r )

19

20 i f choice==1

21 % r a d i a l b a s i s with compact support

22 Phi=@( r ) h e a v i s i d e (1−r ) ∗ (1−r ) ˆ6 ∗ (35∗ r ˆ2 + 18∗ r +3) ;

23 dPhi=@( r ) h e a v i s i d e (1−r ) ∗ (1−r ) ˆ5 ∗ (−280∗ r −56) ; % f i r s t d e r i v a t i v e divided by

r

24 ddPhi=@( r ) h e a v i s i d e (1−r ) ∗ (1−r ) ˆ4 ∗ (1960∗ r ˆ2 − 224∗ r −56) ;

25 e l s e i f choice==2

26 % r a d i a l b a s i s with no compact support

27 % no compact support

28 Phi=@( r ) exp(−r ˆ2) ;

29 dPhi=@( r ) −2∗exp(−r ˆ2) ; % f i r s t d e r i v a t i v e divided by r

30 ddPhi=@( r ) (−2+4∗r ˆ2) ∗ exp(−r ˆ2) ;

31 e l s e

32 e r r o r ( ’ Choice of r a d i a l b a s i s not c o r r e c t . Choices : 1 = compact support , 2 = no

compact support ’ )

33

34 end

35

36 %% Create matrix equation and obtain c o e f f i c i e n t vector

37

38 % Create an Nx2 matrix containing a l l the nodes

39 X=zeros (N, 2 ) ;

40 k=1;

41 f o r i =1:N2

42 f o r j =1:N1

43 X(k , 1 )=x ( j ) ;

44 X(k , 2 )=y ( i ) ;

45 k=k+1;

46 end

47 end

48

79](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-90-320.jpg)

![49 % Create matrix A

50 A=zeros (N,N) ;

51 f o r i =1:N

52 f o r j =1:N

53

54 r=norm(X( i , : )−X( j , : ) ) / delta ; % −−> p h i j

55

56 i f ( X( i , 1 )==1 | | X( i , 2 )==1 | | X( i , 1 )==0 | | X( i , 2 ) ==0) % on the boundary

57 A( i , j )= Phi ( r ) ;

58

59 e l s e % f o r i n t e r n a l nodes

60 dphi x= ((X( i , 1 )−X( j , 1 ) ) /( delta ˆ2 ) ) ∗dPhi ( r ) ; % we mu lti plie d by r and

divided dPhi by r

61 dphi y= ((X( i , 2 )−X( j , 2 ) ) /( delta ˆ2 ) ) ∗dPhi ( r ) ;

62 grad= [ dphi x , dphi y ] ’ ;

63 % dphi xx= (1/( delta ˆ2 )−(X( i , 1 )−X( j , 1 ) ) ˆ2/( delta ˆ4 ∗ r ˆ2) ) ∗dPhi ( r ) +((X( i

, 1 )−X( j , 1 ) ) ˆ2/( delta ˆ4 ∗ r ˆ2) ) ∗ddPhi ( r ) ;

64 % dphi yy= (1/( delta ˆ2 )−(X( i , 2 )−X( j , 2 ) ) ˆ2/( delta ˆ4 ∗ r ˆ2) ) ∗dPhi ( r ) +((X( i

, 2 )−X( j , 2 ) ) ˆ2/( delta ˆ4 ∗ r ˆ2) ) ∗ddPhi ( r ) ;

65 l a p l a c i a n= (1/ delta ˆ2) ∗dPhi ( r ) +(1/ delta ˆ2) ∗ddPhi ( r ) ;

66 % l a p l a c i a n = dphi xx+dphi yy −> t h i s way we can avoid divi ding by r

67 % which i s zero f o r diagonal e n t r i e s

68 A( i , j )= −e p s i l o n ∗ ( l a p l a c i a n ) + [ 1 , 2 ] ∗ grad ;

69 end

70

71

72 end

73 end

74

75 % create RHS vector b

76 b=zeros (N, 1 ) ;

77 f o r i =1:N

78 i f (X( i , 1 ) ==0) % f o r x=0

79 b( i )= (1−exp(−2∗(1−X( i , 2 ) ) / e p s i l o n ) ) /(1−exp(−2/ e p s i l o n ) ) ;

80 e l s e i f (X( i , 2 ) ==0) % f o r y=0

81 b( i )= (1−exp(−(1−X( i , 1 ) ) / e p s i l o n ) ) /(1−exp(−1/ e p s i l o n ) ) ;

82 e l s e % a l l other nodes

83 b( i )= 0;

84 end

85 end

86

87

88

89 % Solve to get c o e f f i c i e n t vector

90 c=Ab ;

91

92

93 %% Add up c o e f f i c i e n t s to obtain s o l u t i o n vector Us

94 N1sol =30;

95 N2sol =30;

96

97 xsol=l i n s p a c e (0 ,1 , N1sol ) ;

98 ysol=l i n s p a c e (0 ,1 , N2sol ) ;

99 Nsol=N1sol ∗ N2sol ;

100

101 Xsol=zeros (N, 2 ) ;

102 k=1;

103 f o r i =1: N2sol

104 f o r j =1: N1sol

105 Xsol (k , 1 )=xsol ( j ) ;

106 Xsol (k , 2 )=ysol ( i ) ;

107 k=k+1;

108 end

109 end

110

111 Us=zeros ( Nsol , 1 ) ;

112 f o r i =1: Nsol

113 dummy=0;

80](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-91-320.jpg)

![114 f o r j =1:N

115 dummy=dummy+c ( j ) ∗Phi (norm( Xsol ( i , : )−X( j , : ) ) / delta ) ;

116 end

117 Us( i )=dummy;

118 end

119

120

121 %% Arrange s o l u t i o n in a matrix to plot

122 k=1;

123 U=zeros ( N2sol , N1sol ) ;

124 f o r i =1: N2sol

125 f o r j =1: N1sol

126 U( i , j )=Us( k ) ; % in f i r s t row y=y1 , second row y=y2 , etc .

127 k=k+1;

128 end

129 end

130

131 %% plot numerical and exact s o l u t i o n

132

133

134 f i g u r e (1)

135 % numerical s o l u t i o n

136 subplot (2 ,1 ,1)

137 s u r f ( xsol , ysol ,U) ;

138 view ( [ 4 0 , 6 5 ] ) ; % viewpoint s p e c i f i c a t i o n

139 axis ( [ 0 1 0 1 0 1 ] )

140 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’ y ’ ) ; z l a b e l ( ’Unumer ’ ) ;

141

142

143 subplot (2 ,1 ,2)

144 % exact s o l u t i o n

145 Z1=(1−exp(−(1− xsol ) / e p s i l o n ) ) /(1−exp(−1/ e p s i l o n ) ) ;

146 Z2= (1−exp(−2∗(1− ysol ) / e p s i l o n ) ) /(1−exp(−2/ e p s i l o n ) ) ;

147 Uexact=Z2 ’∗ Z1 ;

148 s u r f ( xsol , ysol , Uexact ) ;

149 view ( [ 4 0 , 6 5 ] ) ;

150 axis ( [ 0 1 0 1 0 1 ] )

151 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’ y ’ ) ; z l a b e l ( ’ Uexact ’ ) ;

152

153

154 %% Error

155 f i g u r e (2)

156

157 subplot (2 ,1 ,1)

158 s u r f ( xsol , ysol ,U) ;

159 view ( [ 4 0 , 6 5 ] ) ; % viewpoint s p e c i f i c a t i o n

160 axis ( [ 0 1 0 1 0 1 ] )

161 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’ y ’ ) ; z l a b e l ( ’Unumer ’ ) ;

162

163 subplot (2 ,1 ,2)

164 Error=abs ( Uexact−U) ;

165 s u r f ( xsol , ysol , Error )

166 view ( [ 4 0 , 6 5 ] ) ;

167 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’ y ’ ) ; z l a b e l ( ’ Error ’ ) ;

168

169

170 end

F.2 Galerkin Formulation

F.2.1 Gal 1D.m

1 function [ X,A, Us ]=Gal 1D ( epsilon , N, choice , delta )

81](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-92-320.jpg)

![2 % Calculates the s o l u t i o n to the ODE

3 % −e p s i l o n ∗u’ ’+u’= 0 , e p s i l o n > 0 , f o r 0<x<1,

4 % with D i r i c h l e t boundary conditions

5 % u (0) =1,

6 % u (1) =0.

7 % Method : Galerkin Formulation

8 % Radial b a s i s function of the form p h i j = Phi ( r )

9 % where r =|x−x j |/ delta .

10 % Artemis Nika 2014

11

12

13

14 %% D i s c r e t i z a t i o n in x−d i r e c t i o n :

15

16 % Equispaced points

17 x= l i n s p a c e (0 ,1 ,N) ;

18

19 % Parameters

20 theta= −1 ;

21 sigma= 5/(1/N) ;

22 alpha= 1;

23

24 %% Create Matrix Equation

25 A= zeros (N,N) ; % i n i t i a l i z e matrix

26 F= zeros (N, 1 ) ; % i n i t i a l i z e RHS of matrix equation

27

28

29 i f matlabpool ( ’ s i z e ’ ) == 0 % checking to see i f my pool i s already open

30 matlabpool open

31 end

32

33

34 parfor i =1:N % execute loop i t e r a t i o n s in p a r a l l e l

35 [ a , b]= c a l c u l a t e ( i , theta , sigma , alpha , epsilon , delta , choice ,N, x) ;

36 A( i , : )= a ;

37 F( i )= b ;

38 end

39

40

41

42 % Solve equation to obtain c o e f f i c i e n t s

43 c= AF;

44

45 %% Add up c o e f f i c i e n t s to obtain s o l u t i o n vector Us

46 Nsol= 100;

47 Us= zeros ( Nsol , 1 ) ;

48 X= l i n s p a c e (0 ,1 , Nsol ) ;

49

50 i f ( choice == 1)

51 Phi= @( r ) h e a v i s i d e (1−r ) ∗ (1−r ) ˆ5 ∗(8∗ r ˆ2 + 5∗ r + 1) ;

52 e l s e

53 Phi= @( r ) exp(−r ˆ2) ;

54 end

55

56 h=1/(N−1) ;

57 f o r i= 1: Nsol

58 dummy= 0;

59 f o r j= 1:N

60 dummy= dummy+c ( j ) ∗Phi ( abs (X( i )−x ( j ) ) / delta ) ;

61 end

62 Us( i )= dummy;

63 end

64

65

66 %% Exact Solution

67

68 uExact= (1− exp ((X−1)/ e p s i l o n ) ) /(1−exp(−1/ e p s i l o n ) ) ;

69

82](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-93-320.jpg)

![70

71 %% Error

72 Error= zeros ( Nsol , 1 ) ;

73 f o r i= 1: Nsol

74 Error ( i )= abs (Us( i )−uExact ( i ) ) ;

75 end

76

77 %% Plots

78 f i g u r e (1)

79

80 subplot (2 ,1 ,1)

81

82 plot (X, Us , ’ r ’ , ’ LineWidth ’ ,2) ;

83 axis ( [ 0 , 1 , 0 , 1 . 5 ] ) ;

84 s t r=s p r i n t f ( ’ e p s i l o n= %f , delta= %f , s t e p s i z e h= %f ’ , epsilon , delta , h) ;

85 t i t l e ( s t r ) ;

86 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’ Numerical Solution ’ ) ;

87

88 subplot (2 ,1 ,2)

89 plot (X, Error , ’k−∗ ’ )

90 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’ Error ’ ) ;

91

92 f i g u r e (2)

93

94 hold on

95 plot (X, Us , ’ r−∗ ’ , ’ LineWidth ’ ,2) ;

96 plot (X, uExact , ’ LineWidth ’ ,2) ;

97 axis ( [ 0 , 1 , 0 , 1 . 5 ] ) ;

98 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’u ’ ) ;

99 legend ( ’ Numerical Solution ’ , ’ Exact Solution ’ )

100 t i t l e ( s t r ) ;

101 hold o f f

102

103

104

105 end

106

107 % D e f i n i t i o n of function c a l c u l a t e ()

108 function [ a , b]= c a l c u l a t e ( i , theta , sigma , alpha , epsilon , delta , choice ,N, x)

109 i f ( choice==1)

110 p h i i= @(X) h e a v i s i d e (1−abs (X−x ( i ) ) / delta ) .∗ (1−abs (X−x( i ) ) / delta ) .ˆ5

. ∗ ( 8 ∗ ( abs (X−x( i ) ) / delta ) .ˆ2 + 5∗( abs (X−x( i ) ) / delta ) + 1) ;

111 d p h i i= @(X) h e a v i s i d e (1−abs (X−x ( i ) ) / delta ) .∗ (1−abs (X−x( i ) ) / delta ) .ˆ4 .∗

(−56∗( abs (X−x( i ) ) / delta ) .ˆ2 − 14∗( abs (X−x( i ) ) / delta ) ) ;

112 e l s e

113 p h i i= @(X) exp(−(abs (X−x ( i ) ) / delta ) . ˆ 2 ) ;

114 d p h i i= @(X) −2∗(abs (X−x( i ) ) / delta ) .∗ exp(−(abs (X−x ( i ) ) / delta ) . ˆ 2 ) ;

115

116 end

117 a=zeros (1 ,N) ;

118 f o r j =1:N

119 i f ( choice==1)

120 % Wendland function − Compact support

121 p h i j= @(X) h e a v i s i d e (1−abs (X−x ( j ) ) / delta ) .∗ (1−abs (X−x( j ) ) / delta ) .ˆ5

. ∗ ( 8 ∗ ( abs (X−x( j ) ) / delta ) .ˆ2 + 5∗( abs (X−x( j ) ) / delta ) + 1) ;

122 dph i j= @(X) h e a v i s i d e (1−abs (X−x ( j ) ) / delta ) .∗ (1−abs (X−x( j ) ) / delta ) .ˆ4

.∗ (−56∗( abs (X−x ( j ) ) / delta ) .ˆ2 − 14∗( abs (X−x( j ) ) / delta ) ) ;

123

124 e l s e

125 % Gaussian function

126 p h i j= @(X) exp(−(abs (X−x ( j ) ) / delta ) . ˆ 2 ) ;

127 dph i j= @(X) −2∗(abs (X−x ( j ) ) / delta ) .∗ exp(−(abs (X−x( j ) ) / delta ) . ˆ 2 ) ;

128 end

129

130 Function1= @(X) ( e p s i l o n ∗( sign (X−x ( j ) ) / delta ) ) .∗ dp hi j (X) . ∗ ( sign (X−x ( i ) ) /

delta ) .∗ d p h i i (X) + ( sign (X−x( j ) ) / delta ) .∗ dph i j (X) .∗ p h i i (X) ;

131 term1= e p s i l o n ∗( theta ∗ p h i j (1) ∗( sign (1−x( i ) ) / delta ) ∗ d p h i i (1)− ( sign (1−x( j ) )

/ delta ) ∗ dph i j (1) ∗ p h i i (1) ) ;

83](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-94-320.jpg)

![132 term2= e p s i l o n ∗( theta ∗ p h i j (0) ∗( sign (0−x( i ) ) / delta ) ∗ d p h i i (0)− ( sign (0−x( j ) )

/ delta ) ∗ dph i j (0) ∗ p h i i (0) ) ;

133 term3= sigma ∗( p h i i (1) ∗ p h i j (1) +p h i i (0) ∗ p h i j (0) ) ;

134 term extra1= −p h i j (0) .∗ p h i i (0) ;

135 a ( j )= i n t e g r a l ( Function1 , 0 , 1 ) + term1 − term2 + term3 − alpha ∗ term extra1 ;

136 end

137

138 term extra2= − 1∗ p h i i (0) ;

139 b= − e p s i l o n ∗ theta ∗( sign (0−x( i ) ) / delta ) ∗ d p h i i (0) + sigma ∗ p h i i (0) −alpha ∗

term extra2 ;

140

141

142

143 end

F.2.2 Gal 2D.m

1 function [ xsol , ysol ,A,U ]=Gal 2D ( epsilon , N1, N2, choice , delta )

2 % Calculates the s o l u t i o n to the PDE

3 % −e p s i l o n ∗( u xx + u yy ) + (1 ,2) ∗grad (u) =0, (x , y ) in (0 ,1) ˆ2 ,

4 % with boundary conditions

5 % u (1 , y )=u(x , 1 )=0

6 % u (0 , y )=(1−exp(−2∗(1−y ) / e p s i l o n ) ) /(1−exp(−2/ e p s i l o n ) )

7 % u(x , 0 ) =(1−exp(−2∗(1−x ) / e p s i l o n ) ) /(1−exp(−1/ e p s i l o n ) ) ,

8 % using r a d i a l b a s i s f u n c t i o n s

9 % Method : Galerkin formulation

10 % Artemis Nika 2014

11

12 %% D i s c r e t i z a t i o n in x and y d i r e c t i o n

13 x=l i n s p a c e (0 ,1 ,N1) ;

14 y=l i n s p a c e (0 ,1 ,N2) ;

15 N=N1∗N2 ; % t o t a l number of nodes

16

17 %% Parameters

18 theta= −1;

19 sigma= 5/(1/N1) ;

20 alpha= 0;

21

22

23

24 %% Create Matrix Equation

25 A= zeros (N,N) ; % i n i t i a l i z e matrix

26 F= zeros (N, 1 ) ; % i n i t i a l i z e RHS of matrix equation

27

28 % Create an Nx2 matrix containing a l l the nodes

29 X= zeros (N, 2 ) ;

30 k= 1;

31 f o r i= 1:N2

32 f o r j =1:N1

33 X(k , 1 )= x( j ) ;

34 X(k , 2 )= y( i ) ;

35 k= k+1;

36 end

37 end

38

39 i f matlabpool ( ’ s i z e ’ ) == 0 % checking to see i f my pool i s already open

40 matlabpool open

41 end

42

43 parfor i =1:N % execute loop i t e r a t i o n s in p a r a l l e l

44 [ a , b ] =c a l c u l a t e ( i , theta , sigma , alpha , epsilon , delta , choice ,N,X) ;

45 A( i , : )= a ;

46 F( i )= b ;

47 end

48

84](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-95-320.jpg)

![49

50 % Solve to get c o e f f i c i e n t vector

51 c=AF;

52

53

54 %% Add up c o e f f i c i e n t s to obtain s o l u t i o n vector Us

55 N1sol =30;

56 N2sol =30;

57

58 xsol=l i n s p a c e (0 ,1 , N1sol ) ;

59 ysol=l i n s p a c e (0 ,1 , N2sol ) ;

60 Nsol=N1sol ∗ N2sol ;

61

62 Xsol=zeros (N, 2 ) ;

63 k=1;

64 f o r i =1: N2sol

65 f o r j =1: N1sol

66 Xsol (k , 1 )=xsol ( j ) ;

67 Xsol (k , 2 )=ysol ( i ) ;

68 k=k+1;

69 end

70 end

71

72 i f ( choice==1)

73 Phi=@( r ) h e a v i s i d e (1−r ) ∗ (1−r ) ˆ6 ∗ (35∗ r ˆ2 + 18∗ r +3) ;

74 e l s e

75 Phi=@( r ) exp(−r ˆ2) ;

76 end

77

78

79 Us=zeros ( Nsol , 1 ) ;

80 f o r i =1: Nsol

81 dummy=0;

82 f o r j =1:N

83 dummy=dummy+c ( j ) ∗Phi (norm( Xsol ( i , : )−X( j , : ) ) / delta ) ;

84 end

85 Us( i )=dummy;

86 end

87

88

89 %% Arrange s o l u t i o n in a matrix to plot

90 k=1;

91 U=zeros ( N2sol , N1sol ) ;

92 f o r i =1: N2sol

93 f o r j =1: N1sol

94 U( i , j )=Us( k ) ; % in f i r s t row y=y1 , second row y=y2 , etc .

95 k=k+1;

96 end

97 end

98

99 %% plot numerical and exact s o l u t i o n

100

101

102 f i g u r e (1)

103 % numerical s o l u t i o n

104 subplot (2 ,1 ,1)

105 s u r f ( xsol , ysol ,U) ;

106 view ( [ 4 0 , 6 5 ] ) ; % viewpoint s p e c i f i c a t i o n

107 axis ( [ 0 1 0 1 0 1 ] )

108 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’ y ’ ) ; z l a b e l ( ’Unumer ’ ) ;

109

110

111 subplot (2 ,1 ,2)

112 % exact s o l u t i o n

113 Z1=(1−exp(−(1− xsol ) / e p s i l o n ) ) /(1−exp(−1/ e p s i l o n ) ) ;

114 Z2= (1−exp(−2∗(1− ysol ) / e p s i l o n ) ) /(1−exp(−2/ e p s i l o n ) ) ;

115 Uexact=Z2 ’∗ Z1 ;

116 s u r f ( xsol , ysol , Uexact ) ;

85](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-96-320.jpg)

![117 view ( [ 4 0 , 6 5 ] ) ;

118 axis ( [ 0 1 0 1 0 1 ] )

119 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’ y ’ ) ; z l a b e l ( ’ Uexact ’ ) ;

120

121

122 %% Error

123 f i g u r e (2)

124

125 subplot (2 ,1 ,1)

126 s u r f ( xsol , ysol ,U) ;

127 view ( [ 4 0 , 6 5 ] ) ; % viewpoint s p e c i f i c a t i o n

128 axis ( [ 0 1 0 1 0 1 ] )

129 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’ y ’ ) ; z l a b e l ( ’Unumer ’ ) ;

130

131 subplot (2 ,1 ,2)

132 Error=abs ( Uexact−U) ;

133 s u r f ( xsol , ysol , Error )

134 view ( [ 4 0 , 6 5 ] ) ;

135 x l a b e l ( ’ x ’ ) ; y l a b e l ( ’ y ’ ) ; z l a b e l ( ’ Error ’ ) ;

136

137

138 end

139

140 % D e f i n i t i o n of function c a l c u l a t e ()

141 function [ a , b ] =c a l c u l a t e ( i , theta , sigma , alpha , epsilon , delta , choice ,N,X)

142 r i=@( x1 , y1 ) ( sqrt (( x1−X( i , 1 ) ) .ˆ2 +(y1−X( i , 2 ) ) . ˆ 2 ) / delta ) ; % norm () does not

work with quad function

143 i f ( choice==1)

144 p h i i= @( x1 , y1 ) h e a v i s i d e (1− r i ( x1 , y1 ) ) .∗ (1− r i ( x1 , y1 ) ) .ˆ6 . ∗ (35∗

r i ( x1 , y1 ) .ˆ2 + 18∗ r i ( x1 , y1 ) +3) ;

145 dphi i dx= @( x1 , y1 ) h e a v i s i d e (1− r i ( x1 , y1 ) ) .∗ (( x1−X( i , 1 ) ) /( delta ˆ2 ) )

.∗(1 − r i ( x1 , y1 ) ) .ˆ5 . ∗ (−280∗ r i ( x1 , y1 ) −56) ;

146 dphi i dy= @( x1 , y1 ) h e a v i s i d e (1− r i ( x1 , y1 ) ) .∗ (( y1−X( i , 2 ) ) /( delta ˆ2 ) )

.∗(1 − r i ( x1 , y1 ) ) .ˆ5 . ∗ (−280∗ r i ( x1 , y1 ) −56) ;

147 e l s e

148 p h i i= @( x1 , y1 ) exp(− r i ( x1 , y1 ) . ˆ 2 ) ;

149 dphi i dx= @( x1 , y1 ) −2∗((x1−X( i , 1 ) ) /( delta ˆ2 ) ) .∗ exp(− r i ( x1 , y1 ) . ˆ 2 ) ;

150 dphi i dy= @( x1 , y1 ) −2∗((y1−X( i , 2 ) ) /( delta ˆ2 ) ) .∗ exp(− r i ( x1 , y1 ) . ˆ 2 ) ;

151 end

152 a=zeros (1 ,N) ;

153 f o r j =1:N

154 r j=@( x1 , y1 ) ( sqrt (( x1−X( j , 1 ) ) .ˆ2 +(y1−X( j , 2 ) ) . ˆ 2 ) / delta ) ;

155

156 i f ( choice==1)

157 p h i j= @( x1 , y1 ) h e a v i s i d e (1− r j ( x1 , y1 ) ) .∗ (1− r j ( x1 , y1 ) ) .ˆ6 .∗ (35∗

r j ( x1 , y1 ) .ˆ2 + 18∗ r j ( x1 , y1 ) +3) ;

158 dphi j dx= @( x1 , y1 ) h e a v i s i d e (1− r j ( x1 , y1 ) ) .∗ (( x1−X( j , 1 ) ) /( delta ˆ2 ) )

.∗(1 − r j ( x1 , y1 ) ) .ˆ5 .∗ (−280∗ r j ( x1 , y1 ) −56) ;

159 dphi j dy= @( x1 , y1 ) h e a v i s i d e (1− r j ( x1 , y1 ) ) .∗ (( y1−X( j , 2 ) ) /( delta ˆ2 ) )

.∗(1 − r j ( x1 , y1 ) ) .ˆ5 .∗ (−280∗ r j ( x1 , y1 ) −56) ;

160 e l s e

161 p h i j= @( x1 , y1 ) exp(−( sqrt (( x1−X( j , 1 ) ) .ˆ2 +(y1−X( j , 2 ) ) . ˆ 2 ) / delta ) . ˆ 2 ) ;

162 dphi j dx= @( x1 , y1 ) −2∗((x1−X( j , 1 ) ) /( delta ˆ2 ) ) . ∗ exp(− r j ( x1 , y1 ) . ˆ 2 ) ;

163 dphi j dy= @( x1 , y1 ) −2∗((y1−X( j , 2 ) ) /( delta ˆ2 ) ) . ∗ exp(− r j ( x1 , y1 ) . ˆ 2 ) ;

164 end

165

166 term1=@( x1 , y1 ) e p s i l o n ∗( dphi j dx ( x1 , y1 ) .∗ dphi i dx ( x1 , y1 ) + dphi j dy ( x1 ,

y1 ) .∗ dphi i dy ( x1 , y1 ) ) + ( dphi j dx ( x1 , y1 ) + 2∗ dphi j dy ( x1 , y1 ) ) .∗ p h i i ( x1 , y1 ) ;

167 term2=@( y1 ) e p s i l o n ∗ (− p h i i (0 , y1 ) .∗ dphi j dx (0 , y1 )+theta ∗ p h i j (0 , y1 ) .∗

dphi i dx (0 , y1 ) ) − sigma∗ p h i j (0 , y1 ) .∗ p h i i (0 , y1 ) ;

168 term3=@( y1 ) e p s i l o n ∗ ( p h i i (1 , y1 ) .∗ dphi j dx (1 , y1 )−theta ∗ p h i j (1 , y1 ) .∗

dphi i dx (1 , y1 ) ) − sigma∗ p h i j (1 , y1 ) .∗ p h i i (1 , y1 ) ;

169 term4=@( x1 ) e p s i l o n ∗ (− p h i i ( x1 , 0 ) .∗ dphi j dy ( x1 , 0 )+theta ∗ p h i j ( x1 , 0 ) .∗

dphi i dy ( x1 , 0 ) ) − sigma∗ p h i j ( x1 , 0 ) .∗ p h i i ( x1 , 0 ) ;

170 term5=@( x1 ) e p s i l o n ∗ ( p h i i ( x1 , 1 ) .∗ dphi j dy ( x1 , 1 )−theta ∗ p h i j ( x1 , 1 ) .∗

dphi i dy ( x1 , 1 ) ) − sigma∗ p h i j ( x1 , 1 ) .∗ p h i i ( x1 , 1 ) ;

171

172 term extra1=@( y1 ) −p h i j (0 , y1 ) .∗ p h i i (0 , y1 ) ;

86](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c24706f7-2946-435e-a97b-0f69adf3d631-150222142222-conversion-gate02/85/Thesis_Main-97-320.jpg)

![173 term extra2=@( x1 ) −2∗ p h i j ( x1 , 0 ) .∗ p h i i ( x1 , 0 ) ;

174

175 yterm=@( y1 ) term2 ( y1 )+term3 ( y1 )−alpha ∗ term extra1 ( y1 ) ;

176 xterm=@( x1 ) term4 ( x1 )+term5 ( x1 )−alpha ∗ term extra2 ( x1 ) ;

177 % quad2d i s f a s t e r than i n t e g r a l 2 , i n t e g r a l i s f a s t e r than quad

178 a ( j )= quad2d ( term1 , 0 , 1 , 0 , 1 )−i n t e g r a l ( yterm , 0 , 1 )− i n t e g r a l ( xterm , 0 , 1 ) ;

179 end

180

181 Fterm extra1=@( y1 ) −p h i i (0 , y1 ) .∗(1 − exp(−2∗(1−y1 ) / e p s i l o n ) ) ./(1 − exp(−2/ e p s i l o n ) ) ;

182 Fterm extra2=@( x1 ) −2∗ p h i i ( x1 , 0 ) .∗(1 − exp(−(1−x1 ) / e p s i l o n ) ) ./ (1−exp(−1/ e p s i l o n ) )

;

183 Fterm1=@( y1 ) (− e p s i l o n ∗ theta .∗ dphi i dx (0 , y1 ) + sigma∗ p h i i (0 , y1 ) ) .∗(1 − exp

(−2∗(1−y1 ) / e p s i l o n ) ) ./(1 − exp(−2/ e p s i l o n ) ) ;

184 Fterm2=@( x1 ) (− e p s i l o n ∗ theta .∗ dphi i dy ( x1 , 0 ) + sigma∗ p h i i ( x1 , 0 ) ) .∗(1 − exp(−(1−

x1 ) / e p s i l o n ) ) ./ (1−exp(−1/ e p s i l o n ) ) ;

185

186 b= i n t e g r a l ( Fterm1 , 0 , 1 ) + i n t e g r a l ( Fterm2 , 0 , 1 ) − alpha ∗( i n t e g r a l ( Fterm extra1

, 0 , 1 ) + i n t e g r a l ( Fterm extra2 , 0 , 1 ) ) ;

187

188

189 end

F.3 Generalised Interpolation

F.3.1 GenInter 1D.m

1 function [ X,A, Us ]=GenInter 1D ( epsilon , N, choice , delta )