This document is a thesis on theoretical and experimental advances in validating boson sampling experiments. On the theoretical side, it develops a new validation scheme based on a zero-transmission law for Sylvester matrices that is better suited for validating scattershot boson sampling. Experimentally, it reports on implementing an existing validation scheme based on a zero-transmission law for Fourier matrices using integrated photonics fabricated with femtosecond laser writing and a quantum fast Fourier transform algorithm. The experimental results observe the predicted suppression effects.

![Introduction

Since the early 1980s, it has been argued [1] that simulating quantum systems is a

very challenging task. One source of difficulty is the number of parameters needed to

characterize a generic quantum system, which grows exponentially with the size of

the system. This means that even only storing the state of a large quantum system is

not feasible with classical computer memories. Furthermore, the number of operations

needed to simulate the temporal evolution of such a system also scales exponentially

with the size. Thus, the only way to avoid this exponential overhead in the evolution

is the use of approximation methods (such as Monte Carlo methods). However, for

many problems of interest, no good approximation scheme are available. It is then still

an open problem whether they can be efficiently simulated with a classical approach.

Hence, it is widely accepted that classical systems cannot in general efficiently simulate

quantum systems. While it is not yet possible to prove it, neither mathematically nor

experimentally, there are strong evidences to believe that this is the case.

This distinction between classical and quantum world has many implications. One

of the most notable examples concerns the possibility that computers exploiting the

weirdnesses of quantum mechanics may be able to carry out computations impossible

with only classical resources. With the current available technologies, the experimental

observation of this quantum advantage (sometimes referred to as quantum supremacy [2,

3]) has proven itself to be rather difficult to achieve. In particular, to observe a post-

classical computation with a universal quantum computer one first needs to solve the

problem of fault-tolerant quantum computation [4], which is known to be possible

in principle [5, 6, 7], but might require decoherence rates that are several orders of

magnitude below what achievable today. In the case of linear optics, a number of no-go

theorems led to the widespread belief that linear interferometry alone could not provide

a path to universal quantum computation. For this reason the result of Aaronson and

Arkhipov (AA), that passive linear optical interferometers with many-photon inputs

cannot be efficiently simulated by a classical computer [8], represented a significant

advance. The related computational problem, that is, sampling from the output proba-

bility distribution of such an apparatus, was named by AA the BosonSampling problem.

A quantum device able to efficiently solve it is referred to as a boson sampler.

More in detail, the BosonSampling computational problem consists in sampling

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-7-320.jpg)

![from the output probability distribution resulting from the time-evolution of n indis-

tinguishable photons into a random m × m unitary transformation. The hardness of

BosonSampling arises from the fact that the scattering amplitude between an input and

an output state configuration is proportional to the permanent of a suitable n×n matrix,

where the permanent is a particular function, defined similarly to the determinant,

which in the general case is known to be hard to compute classically. This immediately

suggests an experimental scheme to build a boson sampler using only linear optical

elements: just inject n indistinguishable photons into an appropriate linear optical

interferometer, and use photon-counting detectors to detect the resulting output states.

AA showed that, already with 20 < n < 30 and m n, this would provide direct

evidence that a quantum computer can solve a problem faster than what is possible with

any classical device. While this regime is far from our current technological capabilities,

several implementations of 2- and 3-photon devices have soon been reported [9, 10, 11,

12], and other more complex implementations followed [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18].

However, the originally proposed scheme to implement BosonSampling, that is,

to generate the input n-photon state through Spontaneous parametric downconver-

sion (SPDC), suffers from scalability problems. Indeed, it is unfeasible to generate high

numbers of indistinguishable input photons with this method, due to the generation

probability decreasing exponentially with n. For this reason, an alternative scheme,

named scattershot boson sampling [19], has been devised [20], and subsequently im-

plemented [18]. Contrarily to a classical boson sampler, a scattershot boson sampler

uses m SPDC sources, one per input mode of the interferometer, to generate random

(but known) n-photon input states, with n m. Each SPDC source generates a pair

of photons, one of which is injected into the interferometer, while the other is used

to herald the SPDC generation event. The use of a scattershot boson sampling scheme

results in an exponential increase of the probability of generating n indistinguishable

photons, for m and n large enough.

While the key part of BosonSampling resides in its simulation complexity, this very

hardness also poses a problem of certification of such a device. Indeed, it is believed [8]

that, when n is large enough, a classical computer cannot even verify that the device is

solving BosonSampling correctly. However, it is still possible to obtain circumstantial

evidence of the correct functioning of a device, and efficiently distinguish the output of

a boson sampler from that resulting from alternative probability distributions, like the

output produced by classical particles evolving through the same interferometer.

A number of validation schemes were subsequently devised to validate the output

resulting from true many-boson interference [14, 16, 21, 22, 23]. In particular, the tests

currently more suitable to identify true many-body interference [22] are those based

on Zero-Transmission Laws (ZTLs) [24]. A ZTL, also often referred to as suppression

law, is a rule which, for certain particular unitary evolutions, is able to predict that

the probability of certain input-output configurations is exactly zero, without having to

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-8-320.jpg)

![compute any permanent.

However, for the current validation schemes based on ZTLs, it is mandatory that

the input states possess particular symmetries. This requirement may thus be an issue

when the ZTLs are applied to validate a scattershot boson sampler. Indeed, the input

state in scattershot boson sampling is not fixed, but changes randomly at each n-photon

generation event. This mandates for a new ZTL-based validation scheme to be devised,

able to efficiently validate a scattershot boson sampling experiment, but still keeping

the capability of distinguishing alternative probability distributions.

In this thesis we report on both theoretical and experimental advances in the context

of validating classical and scattershot boson sampling experiments:

• From the theoretical point of view, we devise a new validation scheme, more

suitable to validate scattershot boson sampling experiments. This scheme, based

on a ZTL valid for a particular class of matrices, the so-called Sylvester matrices,

generalizes the ZTL reported in [23], presenting significantly higher predictive

capabilities.

• From the experimental point of view, we report on the experimental implementa-

tion [25] of the validation scheme proposed in [22] based on the ZTL for Fourier

matrices [24]. To this end, a scalable methodology to implement the Fourier

transformation on integrated photonics was adopted. This approach exploits the

3-D capabilities of femtosecond laser writing technique, together with a recently

proposed [26] quantum generalization of the Fast Fourier transform algorithm

[27], which allows a significant improvement in the number of elementary optical

elements required to implement the desired Fourier transformation.

The thesis is structured as follows: Chapter 1 opens with a brief survey of classical

and quantum computer science. In chapter 2, after a brief exposition of the theoretical

formalism for many-body quantum states, the fundamental tools used in quantum op-

tics experiments are presented. In chapter 3 the BosonSampling problem is introduced.

The problem of scaling boson sampling experiments is discussed, together with the

recently proposed alternative scheme named scattershot boson sampling. In chapter 4

the subject of boson sampling validation is introduced, and an outline of the proposed

solutions is provided. In particular, the focus is on the validation schemes based on

zero-transmission laws for Fourier and Sylvester matrices, and the possibility of apply-

ing them to scattershot boson sampling experiments. In chapter 5 we present a new

zero-transmission law for Sylvester matrices. Exploiting this zero-transmission law, we

present a scheme to validate scattershot boson sampling experiments. The thesis closes

with chapter 6, where we present the experimental implementation of a validation

scheme for Fourier matrices. The experimental and technological aspects of the experi-

ment are discussed, from the femtosecond laser-written technology employed to build

the integrated interferometers, to a novel method to efficiently implement the Fourier

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-9-320.jpg)

![b b b 1 b b b b b b b b

qh

end

. . .. . .

To see this, we have to analyse how the program given to the TM acts on the

initial tape: starting in the state qs on a tape cell with the symbol , the first line of

the program mandates the tape-head to move right and switch to the state q1. In

the q1 state, following the lines 2 and 3, the tape-head will move right over-writing

all the ones and zeros it finds, until it reaches a blank cell. When a blank cell is

reached, according to line 4, the tape-head changes its state to q2 and starts moving

left, continuing moving left, following line 5, until it reaches again the cell. When

the cell is reached, the state is changed to q3 and the tape-head is moved once on the

right. At this point, because of the line 7 of the program, the cell under the tape-head

- that is, the cell on the right of the one with - is over-written to 1, and the tape-head

state changed to qh, halting the execution.

The above analysis shows that this program computes the constant function

f(x) = 1. That is, regardless of what number is given in input onto the tape, the TM

halts with the number 1 represented onto the tape.

In general, a TM can be thought of as computing functions from the non-negative

integers to the non-negative integers, with the input to the function represented by the

initial state of the tape, and the output of the function by the final state of the tape.

The above presented TM is used to formalize the concept of a deterministic algorithm.

To also consider non-deterministic algorithms, this model must however be extended. For

this purpose, the TM model is generalized to that of a probabilistic TM. In a probabilistic

TM, the state transitions are choosen according to some probability distribution, instead

of being completely predetermined.

A further generalization of TMs provides a theoretical basis for quantum algorithms.

These are a special kind of algorithms which, exploiting the properties of quantum

mechanics, can potentially outperform any classical algorithm in certain tasks.

1.2 Church-Turing thesis

An interesting question is what class of functions is it possible to compute using a Turing

machine. Despite its apparent simplicity, the TM model can be used to simulate all

the operations performed on a modern computer. Indeed, according to a thesis put

forward independently by Church and Turing, the TM model completely captures the

notion of computing a function using an algorithm. This is known as the Church-Turing

thesis [28]:

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-14-320.jpg)

![Church-Turing thesis: The class of functions computable by a Turing ma-

chine corresponds exactly to the class of functions which we would naturally

regard as being computable by an algorithm.

The Church-Turing thesis asserts an equivalence between the rigorous mathematical

concept of “function computable by a Turing machine”, and the intuitive concept of

what it means for a function to be computable by an algorithm. In this sense it is

nothing more than a definition of what we mean when we talk of the “computability” of

a function. This thesis is relevant because it makes the study of real-world algorithms

amenable to rigorous mathematical analysis.

We remark that it is not obvious that every function which we would intuitively

regard as computable by an algorithm can be computed using a TM. Indeed, it is conceiv-

able that in the future we will discover in Nature a process which computes a function

not computable by a TM. Up to now, however, no such process has been observed.

Indeed, as will be discussed in more detail in later sections, quantum computers also

obey the Church-Turing thesis. That is, quantum computers can compute the same

class of functions computable by a TM.

A much stronger statement than the Church-Turing thesis is the so-called Extended

Church-Turing thesis (ECT) [8] (also sometimes referred to as Strong Church-Turing

thesis [28]):

Extended Church-Turing thesis: All computational problems that are

efficiently solvable by realistic physical devices, are efficiently solvable by a

Turing machine.

The ECT was however already found to be insufficient to capture all realistic com-

putational models in the 1970s, when Solovay and Strassen [29] devised an efficient,

probabilistic primality test. As the Solovay-Strassen algorithm relied essentially on

randomness, it provided the first evidence that probabilistic Turing machines are capa-

ble to solve certain problems more efficiently than deterministic ones. This led to the

following ad-hoc modification to the ECT:

Extended Probabilistic Church-Turing thesis: All computational prob-

lems that are efficiently solvable by realistic physical devices, are efficiently

solvable by a probabilistic Turing machine.

As this is the form the ECT is currently usually stated as, this is the version we will refer

to when talking in the following of “ECT”.

However, even in this modified form, the ECT still does seem to be in contrast with

the currently accepted physical laws. The first evidence in this direction was given by

Shor [30], which proved that two very important problems - the problem of finding

the prime factors of an integer, and the so-called discrete logarithm problem - could

be solved efficiently on a quantum computer. Since no efficient classical algorithm -

neither deterministic nor probabilistic - is currently known to be able to efficiently solve

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-15-320.jpg)

![these problems, Shor’s algorithm strongly suggests that quantum mechanics allows

to solve certain problems exponentially faster than any classical computer, and this

directly contradicts the ECT.

1.3 Complexity theory

Computational complexity theory analyzes the time and space resources required to

solve computational problems [28]. Generally speaking, the typical problem faced

in computational complexity theory is proving some lower bounds on the resources

required by the best possible algorithm for solving a problem, even if that algorithm is

not explicitly known.

One difficulty in formulating a theory of computational complexity is that different

computational models may lead to different resource requirements for the same problem.

For instance, multiple-tape TMs can solve many problems significantly faster than single-

tape TMs. On the other hand, the strong Church-Turing thesis states that any model of

computation can be simulated on a probabilistic TM with at most a polynomial increase

in the number of elementary operations required. This means that if we make the

coarse distinction between problems which can be solved using resources which are

bounded by a polynomial in n, and those whose resource requirements grow faster than

any polynomial in n, then this distinction will be well-defined and independent of the

considered computational model. This is the chief distinction made in computational

complexity.

With abuse of the term exponential, the algorithms with resource requirements

growing faster than any polynomial in n are said to require an amount of resources

scaling exponentially in the problem size. This includes function like nlog n

, which grow

faster than any polynomial but lower than a true exponential, and are nonetheless said

to be scaling exponentially, in this context. A problem is regarded as easy, tractable, or

feasible, if an algorithm for solving the problem using polynomial resources exists, and

as hard, intractable, or infeasible, if the best possible algorithm requires exponential

resources.

Many computational problems are formulated as decision problems, that is problems

with a yes or no answer. For example, the question is a given number m a prime number

or not? is a decision problem. Although most decision problems can easily be stated in

simple, familiar language, discussions of the general properties of decision problems are

greatly helped by the terminology of formal languages. In this terminology, a language

L over the alphabet Σ is a subset of the set Σ∗

of all finite strings of symbols from Σ.

For example, if Σ = {0, 1}, then the set of binary representations of even numbers

L = {0, 10, 100, 110, . . . } is a language over Σ. A language L is said to be decided by a

TM if for every possible input x ∈ Σ∗

, the TM is able to decide whether x belongs to

L or not. In other words, the language L is decided if the TM will eventually halt in a

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-16-320.jpg)

![state encoding a “yes” answer if x ∈ L, and eventually halt to a state encoding a “no”

answer otherwise.

Decision problems are naturally encoded as problems about languages. For instance,

the primality decision problem can be encoded using the binary alphabet Σ = {0, 1},

interpreting strings from Σ∗

as non-negative integers, and defining the language L to

consist of all binary strings such that the corresponding number is prime. The primality

decision problem is then translated to the problem of finding a TM which decides the

language L. More generally, to each decision problem is associated a language L over

an alphabet Σ∗

, and the problem is translated to that of finding a TM which decides L.

To study the relations between computational problems, it is useful to classify them

into complexity classes, each one grouping all problems (that is, in the case of decision

problems, all languages) sharing some common properties. Most of computational

complexity theory is aimed at defining various complexity classes, and at understanding

of the relationships between different complexity classes.

A brief description of the most important complexity classes for decision problems

is provided in the following:

• P: We say that a given problem is in TIME(f(n)) if there is a deterministic TM

which decides whether a candidate x is in the corresponding language in time

O(f(n)), with n the length of x. A problem is said to be solvable in polynomial

time if it is in TIME(nk

) for some k. The collection of all languages which are in

TIME(nk

), for some k, is denoted P, which is an example of a complexity class

Some examples of problems in P are linear programming, the calculation of the

greatest common divisors of two numbers, and the problem of determining if a

number is prime or not.

Not surprisingly, there are lots of problems for which no polynomial-time algo-

rithm is known. Proving that a given decision problem is not in P, however, is very

difficult. A couple of examples of such problems are 1) given a non-deterministic

Turing machine M and an integer n written in binary, does M accept the empty

string in at most n steps? and 2) given a pair of regular expressions, do they represent

different sets?. Many other problems are believed to not be in P. Among these

are notable ones such as Factoring, which is the problem of finding the prime

factors decomposition of an integer. This problem is believed to hard problem for

classical computers, though no proof, nor compelling evidences for it, are known

to date. Factoring is particularly important, since its hardness lies at the heart

of wisely used algorithms in cryptography such as the RSA cryptosystem [28].

• NP: An interesting property of the prime factorization problem is that, even if

finding the prime factorization of an integer n is very hard, it is easy to check if a

proposed set of primes is indeed the correct factorization of n: just multiply the

numbers and check if they equal n. The class of decision problems sharing this

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-17-320.jpg)

![property is called NP. More generally NP, standing for “nondeterministic poly-

nomial time”, is the class of all decision problems for which there are efficiently

verifiable proofs. A NP problem can often be intuitively stated in the form are

there any solutions that satisfy certain constraints?

While it is clear that P is a subset of NP, the converse is currently not known.

Indeed, whether P equals NP is arguably the most famous open problem in

computer science, often abbreviated as the P = NP problem. Many computer

scientists believe [31, 32, 33] that P = NP. However, despite decades of work,

nobody has been able to prove this, and the possibility that P = NP cannot be

excluded. Some implications of either of these possibilities are shown in fig. 1.1.

A related complexity class is NP-hard, which groups all decision problems that

are, informally, at least as hard as the hardest problems in NP. More precisely, a

problem L is NP-hard if every problem in NP can be reduced to L in polynomial

time. As a consequence, a polynomial algorithm solving an NP-hard would

also automatically provide a polynomial algorithm for all problems in NP. While

this is considered highly unlikely, as many NP problems are believed to not be

solvable in polynomial time, it has never been proved that this is not the case.

Finally, the intersection between NP and NP-hard is the class of the so-called

NP-complete problems.

• BPP: If we extend our definition of a TM allowing it to have access to a source of

randomness, let’s say the ability to flip a fair coin, other complexity classes can

be defined. Such a probabilistic Turing machine may only accept or reject inputs

with a certain probability, but if the probability of an incorrect accept or reject is

low enough, they are as useful as their deterministic counterparts. One of the

most important such classes is BPP, which stands for Bounded-error Probabilistic

Polynomial time. BPP is the class of decision problems solvable by a probabilistic

TM in polynomial time with a probability of error less than 1/3.

The choice of 1/3 as error bound is mostly arbitrary, as any error bound strictly

less than 1/2 can be reduced to practically zero with only a small increase in

the resource requirements. For this reason, problems in BPP are regarded as

as efficiently solvable as P problems. In fact, for practical purposes, BPP is

considered, even more than P, as the class of problems which are efficiently

solvable on a classical computer.

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-18-320.jpg)

![Complexity

P ≠ NP P = NP

NP-Hard

NP-Complete

P

NP

NP-Hard

P = NP =

NP-Complete

Figure 1.1: Relations between the fundamental complexity classes.

All the above considered computational classes only took into account classical

Turing machines. The advent of quantum mechanics and the conception of quantum

computers, however, led to the question of what classes of problems can a quantum

computer solve? To try to answer this question, one must study another kind of

complexity classes, entering the realm of quantum complexity theory. In this context,

arguably the most fundamental complexity class if BQP, standing for Bounded-error

Quantum Polynomial time. This is the quantum generalization of BPP, and is defined

as the set of decision problems solvable by a quantum computer in polynomial time,

with an error probability of at most 1/3 for all instances. Probably the most notable

problem which has been shown to be in BQP is Factoring. Indeed, Shor’s algorithm

[30] was one of the first devised quantum algorithms able to efficiently solve a problem

that the best-known classical counterparts can solve only in exponential time.

While only decision problems have been mentioned to this point, these are not the

only kind of computational problems. Function problems are a generalized version of

decision problems, where the output of the algorithm is not bounded to be a simple

YES/NO answer. More formally, a function problem P is defined as a relation R over

the cartesian product over strings of an alphabet Σ, that is R ⊂ Σ∗

× Σ∗

. An algorithm

is said to solve P if for every pair (x, y) ∈ R, it produces y when given x as input.

A class of function problems that will be of interest in the following are the so-called

counting problems, which are problems that can be stated as how many X satisfy a certain

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-19-320.jpg)

![property P? An example of such a complexity class is #P (pronounced “sharp P”), which

is the set of counting problems associated with the decision problems in NP. Intuitively,

to each NP problem which can be stated in the form “Are there any solutions having

the property P?” is associated a #P problem which can be stated in the form “How many

solutions are there which satisfy the property P?”. As can be intuitively deduced from

this definition, #P problems are generally believed to be even more difficult than NP

problems.

A pair of computational classes related to #P are #P-hard and #P-complete. These

are defined in a completely analogous way to NP-hard and NP-complete, containing

the class of counting problems at least as hard as any #P problem.

A notable instance of a #P-hard problem is the calculation of the permanent of a

complex-valued matrix. The permanent is a function of matrices defined similarly to

the determinant (see the discussions in the following sections, like definition 2), but

which, contrarily to the latter, is known to not be computable in polynomial time, for

general matrices [34]. Indeed, the problem of computing the permanent of a matrix is

known to be a #P-hard problem, and even #P-complete in special circumstances [34].

1.4 Quantum information and quantum computation

Quantum information theory [28, 35, 36, 37] is the study of the information processing

tasks that can be accomplished using quantum mechanical systems. One of the main

goals of quantum information theory is to investigate how information is stored in the

state of a quantum system, how does it differ from that stored in a classical system, and

how can this difference be exploited to build quantum devices with capabilities superior

to that of their classical counterparts. To this end several concepts and ideas are drawn

from other disciplines, such as quantum mechanics, computer science, information

theory, and cryptography, and merged with the goal of generalizing the concepts of

information and computing to the quantum realm.

In the last few decades, information and computation theory have undergone a

spurt of new growth, expanding to treat the intact transmission and processing of

quantum states, and the interaction of such quantum information with traditional forms

of information. We now know that a fully quantum theory of information offers, among

other benefits, a brand of cryptography whose security rests on fundamental physics,

and a reasonable hope of constructing quantum computers that could dramatically speed-

up the solution of certain mathematical problems. Moreover, at a more fundamental

level, it has become clear that an information theory based on quantum principles

extends and completes classical information theory, much like complex numbers extend

and complete the reals. One of the conceptual building blocks of quantum information

and quantum computation is that of a qubit. This is the quantum generalization of

the classical concept of bit, and the fundamental processing unit of most quantum

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-20-320.jpg)

![devices. While a bit can be in one of two states, traditionally referred to as 0 and 1, a

qubit is allowed to be in a superposition of these basis states. Properly handling such

qubits, quantum computers are able to process information in ways impossible with

any classical computer.

The first to envisage the notion of a quantum computer was Feynman [1], as a

possible solution to the problem of the exponentially increasing amount of resources

required to simulate complex quantum systems with classical computers. More than a

decade later, Lloyd [38] showed that a quantum computer can indeed act as a universal

quantum simulator, where the word universal refers to the fact that the same machine

is capable of tackling vastly different problems by simply changing the program it runs.

There are a lot of candidate implementations for quantum computation. Among

these, in no particular order, are implementations using superconductors, trapped

ions, quantum dots, nuclear magnetic resonance, diamond nitrogen vacancies, silicon,

linear optics, and many other proposed technologies. Here we will only focus on linear

optical implementations of quantum computing, to highlight the difficulties inherent

to implement universal quantum computers, as opposite to the relatively much easier

demands of boson sampling devices, which will be described in the following sections.

Linear optics quantum computation (LOQC) with single photons has the advan-

tage that photons have very long decoherence times, which means that the quantum

information stored in photons tends to stay there, and that linear optical elements are

arguably the simplest building blocks to realize quantum information processing. The

downside is that photons do not naturally interact with each other, and in order to

apply two-qubit quantum gates, which are necessary to implement universal quantum

computation, such interactions are essential. Because of this, effective interactions

among photons have to be introduced somehow.

The two main methods to implement such interactions among photons are 1) using

Kerr nonlinearities, and 2) the use of projective measurements with photodetectors.

Unfortunately, present-day nonlinear Kerr media exhibit very poor efficiency [28] and

very weak nonlinearities, while projective measurements have the disadvantage of

producing probabilistic quantum gates: more often than not these gates fail, destroying

the quantum information.

In the case of projective-measurements-induced nonlinearities there is however

a way to avoid the issue of nondeterministic gates, still mantaning feasible resource

requirements: the Knill, Laflamme, and Milburn [7] (KLM) scheme. Introduced in 2001,

the KLM protocol allows scalable linear optics quantum computing by using quantum

gate teleportation to increase the probability of success of nondeterministic gates [7, 39,

40]. The downside of the KLM scheme is that, for its implementation, it is still necessary

to overcome a series of experimental challenges, such as the synchronization of pulses,

mode-matching, quickly controllable delay lines, tunable beam splitters and phase

shifters, single-photon sources, accurate, fast, single-photon detectors, and extremely

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-21-320.jpg)

![fast feedback control of these detectors. While most of these features are not terribly

unrealistic to implement, the experimental state of the art is simply not at the point at

which more complex gate operations such as two-qubit operations can be implemented.

On the other hand, a quantum computer is not necessary to implement quantum

simulation. Dropping the requirement of being able to simulate any kind of system,

special purpose devices can be built to tackle specific problems better than the clas-

sical counterparts, in the simpler conceivable case by just emulating, in an analog

manner, the behaviour of a complex quantum system on a simpler quantum device.

Being generally these special purpose devices easier to implement than full-fledged

quantum computers, it is expected that practical quantum simulation will become a

reality well before quantum computers. However, despite the undeniable practical

usefullness of implementing quantum simulation on a classically intractable quantum

system, this would hardly give a definite answer to the question: are there tasks which

quantum computers can solve exponentially faster than any classical computer? Indeed,

a quantum system that is hard to classically simulate is also typically hard to define as

a computational problem. This makes extremely difficult to definitively prove whether

a classical algorithm, able to efficiently carry out such a simulation, exists.

It is for this reasons that the proposal of a boson computer by Aaronson and Arkhipov

[8] gained much interest in the quantum optics community. This kind of special purpose

linear optics quantum computer requires only to send n indistinguishable photons

through a random unitary evolution, and detect the output photons with standard

photodetectors. No teleportation or feedback mechanisms are required, which makes

the experimental implementation of such a device much easier than that of a quantum

computer following the KLM scheme. Furthermore, the related computational problem

is simple enough to be analytically tractable with the tools of computational complexity,

allowing to obtain very strong theoretical evidence of its hardness.

22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-22-320.jpg)

![sufficient to obtain the wave function at each time t: its solution is, at least formally,

given by |Ψ(t) = e−i(t−t0)H/

|Ψ(t0) .

The above described formalism is also called first-quantization, to distinguish it

from another way of dealing with quantum systems, named second-quantization. The

latter differs from the former by a shift in focus: instead of considering the number

of particles as a fixed property of the system and using the wave function to describe

their states, the system is characterized by the number of particles contained in each

possible mode, which are however no longer necessarily fixed. To this end, a creation

operator is defined, for each mode, as an operator which acts on a quantum state and

produces another quantum state differing from the former for a single quantum added

to that mode. The hermitian conjugate of a creation operator is called an annihilation

operator (also destruction operator), and instead of adding a quantum to a given mode,

it does the opposite, producing a new state with one less particle in the mode.

The exact rules followed by creation and annihilation operators depend on the

statistical nature of the particles. For bosons, the creation (annihilation) operator of a

mode labelled i is denoted ˆa†

i (ˆai). The core rules obeyed by these operators are the

following:

ˆai |ni =

√

n |(n − 1)i , ˆa†

i |ni =

√

n + 1 |(n + 1)i ,

[ˆak, ˆa†

q] = δk,q, [ˆak, ˆaq] = [ˆa†

k, ˆa†

q] = 0 ,

(2.3)

where |ni is a state with n particles in the mode labelled i. Quantum states with a

well-defined number of particles in each mode are called Fock states, or number states,

and the set of all Fock states is called Fock space.

The above defined creation operators can be used to denote many-boson states, that

is, quantum states with more than one indistinguishable boson. If any single boson can

be in one of m modes, an n-boson state r having ri particles in the i-th mode will be

written as

|r ≡ |r1, . . . , rm =

1

√

r!

m

k=1

ˆa†

k

rk

|0 . (2.4)

where the notation r! ≡ r1! · · · rk! has been used. Such a list r of m elements, with each

element equal to the number of particles in a given mode, will be referred to as the

Mode Occupation List (MOL) associated to the quantum state. A many-body state such

that for every k = 1, . . . , m, rk = 1 or rk = 0, is said to be a collision-free state.

Another way to characterize many-body states is through a so-called Mode Assign-

ment List (MAL) R . This is a list of n elements, with the i-th element being the mode

occupied by the i-th particle. It is worth noting that for indistinguishable particles one

cannot talk of “the mode of the i-th particle”, however. Because of this, the order of

the elements of MALs cannot have any physical significance. In other words, MALs are

always defined up to the order of the elements, or, equivalently, they must be always

considered conventionally sorted (for example, in increasing order). Representing the

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-24-320.jpg)

![state with a MAL, eq. (2.4) can be rewritten in the following form:

|r ≡ |R =

1

√

r!

n

k=1

ˆa†

Rk

|0 =

1

µ(R)

n

k=1

ˆa†

Rk

|0 , (2.5)

where we denoted with µ(R) the product of the factorials of the occupation numbers

of the state R, that is, µ(R) ≡ r1! · · · rm!.

Yet another way to describe many-body states that will sometimes be useful is to

explicitly list the occupation numbers of each mode. For example, for a state with three

particles, one in the second mode and two in the fourth mode, we write |12, 24 . If

we want to emphasize the absence of particles in, say, the third mode, we write it as

|12, 03, 24 .

Definition 1 (MOL and MAL representations). All of the many-particle quantum

states used in the following will be assumed to have a fixed number of particles n,

with each particle potentially occupying one of m possible modes. Two ways to

represent a state are:

• As the Mode Occupation List (MOL) r ≡ (r1, . . . , rm), i.e. as the m-dimensional

vector whose element rk is the number of particles in the k-th mode. It follows

from this definition that m

k=1 rk = n. We will refer to this representation as

the MOL representation, and denote with Fn,m the set of all MOLs of n photons

into m modes, and with FCF

n,m the set of collision-free MOLs of n photons into

m modes:

Fn,m ≡ (r1, . . . , rm) | ∀i = 1, . . . , m, ri ≥ 0 and

m

i=1

ri = n , (2.6)

FCF

n,m ≡ {(r1, . . . , rm) ∈ Fn,m | ∀i = 1, . . . , m, ri ∈ {0, 1}} . (2.7)

• As the Mode Assignment List (MAL) R ≡ (R1, . . . , Rn), i.e. as the n-dimensional

vector listing the modes occupied by the particles. Given that for indistinguish-

able particles it is not meaningful to assign a specific mode to a specific particle,

the order of the elements of a MAL are conventionally taken to be in increas-

ing order, so to have a one-to-one correspondence between physical states

and MALs. We will refer to this representation as the MAL representation of a

many-particle quantum state and, following the notation of [41], denote with

Gn,m and Qn,m the set of all MALs of n photons into m modes and the set of

collision-free MALs of n photons into m modes, respectively. Equivalently, Gn,m

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-25-320.jpg)

![Using eq. (2.5) into eq. (2.10) gives

|r

ˆU

−−−−→

1

√

r!

n

k=1

m

j=1

URk,j

ˆb†

j

|0 =

1

√

r!

m

j1=1

m

j2=1

· · ·

m

jn=1

n

k=1

URk,jk

ˆb†

jk

|0

=

1

√

r! ω∈Γn,m

n

k=1

URk,ω(k)

ˆb†

ω(k) |0 ,

(2.13)

where Γn,m is the set of all sequences of n positive integers lesser than or equal to m.

To compute the scattering amplitudes A(r → s, U) of going from the input r to the

output s ≡ (s1, . . . , sn), we now have to rearrange the terms on the right hand side of

eq. (2.13). To this end we start from the general combinatorial equation (see [41]):

ω∈Γn,m

f(ω1, . . . , ωn) =

ω∈Gn,m

1

µ(ω) σ∈Sn

f(ωσ(1), . . . , ωσ(n)), (2.14)

where f(ω) ≡ f(ω1, . . . , ωn) is any function of n integer numbers, Gn,m is the sequence

of all non-decreasing sequences of n positive integers lesser than or equal to m, given

in definition 1, and Sn is the symmetric group, that is, the set of permutations of n

elements.

Applying eq. (2.14) to eq. (2.13), with f(ω1, . . . , ωn) = n

k=1 URkωk

ˆb†

ωk

, we obtain

|r

ˆU

−−−−→

1

µ(R) ω∈Gn,m

1

µ(ω) σ∈Sn

n

k=1

URk,ωσ(k)

ˆb†

ωσ(k)

|0

=

ω∈Gn,m

1

µ(R)µ(ω)

σ∈Sn

n

k=1

URk,ωσ(k)

|ω1, . . . , ωn out ,

(2.15)

where in the last step we exploited the commutativity of the product of the creation

operators ˆb†

k.

We thus obtained the following expression for the scattering amplitudes for bosonic

particles:

A(r → s, U) ≡ out s|r ≡ s| ˆU |r =

1

µ(R)µ(S)

σ∈Sn

n

k=1

URk,Sσ(k)

, (2.16)

in which the factor on the right hand side can be recognised as the permanent of an

appropriate matrix built from U.

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-28-320.jpg)

![Definition 2 (Permanent). The permanent of a square matrix, similarly to the de-

terminant, is a function which associates a number to a matrix. It is defined very

similarly to the determinant, with the exception that all minus signs that are present

for the latter become plus signs in the former.

More precisely, the permanent of a squared n×n matrix A = (aij) is

perm(A) =

σ∈Sn

a1,σ(1) · · · an,σ(n) =

σ∈Sn

n

k=1

ak,σ(k), (2.17)

where Sn is the symmetric group, that is, the set of all permutations of n distinct

objects.

To express eq. (2.16) through the above defined permanent function, it is also useful

to introduce the following notations to refer to particular submatrices built from a given

matrix:

Definition 3. Let Mk,l denote the set of all k×l complex-valued matrices. If k = l

we shall write Mk instead of Mk,k. Now, let A ∈ Mk,l, and let α ∈ Gp,k and β ∈ Gq,l.

Then, we shall denote with A[α|β] the p × q dimensional matrix with elements

A[α|β]i,j ≡ Aαi,βj

. If, moreover, α ∈ Qp,k and β ∈ Qq,l, then A[α|β] is a submatrix

of A. If α = β we will simplify the notation to write A[α] instead of A[α|β].

Again, if α ∈ Qp,k and β ∈ Qq,l, we shall denote with A(α|β) the (k − p)×(l − q)

dimensional submatrix of A complementary to A[α|β], that is, the submatrix obtained

from A by deleting rows α and columns β.

Example 4. Consider the 3×4 dimensional matrix A =

1 2 3 0

4 5 6 i

0 4 2 1

. Then, if

α = (1, 1) ∈ G2,4 and β = (2, 4, 4) ∈ G3,3, we have A[α|β] ≡

2 0 0

2 0 0

. If

instead α = (2, 3) ∈ Q2,4 and β = (1, 2) ∈ Q2,3, we have A[α|β] ≡

4 5

0 4

and

A(α|β) ≡ 3 0 .

Using definitions 2 and 3, we see that for any matrix A ∈ Mm and sequences

α, β ∈ Gn,m, we have

perm(A[α|β]) =

σ∈Sn

n

k=1

Aαk,βσ(k)

,

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-29-320.jpg)

![which is just the factor in brackets on the right hand side of eq. (2.16). We conclude that

A(r → s, U) ≡ out s|r ≡ s| ˆU |r =

1

µ(R)µ(S)

perm(U[R|S]). (2.18)

It is worth noting that the symmetric nature of the bosonic creation operators - that

is, the fact that [ˆa†

i , ˆa†

j] = δij - was essential in the above derivation. Analogous

reasonings carried out using fermionic particles - whose creation operators satisfy

{ˆc†

i , ˆc†

j} ≡ c†

i c†

j + c†

jc†

i = δij - would lead to the result

Afermions

(r → s, U) = det(U[R|S]). (2.19)

While eqs. (2.18) and (2.19) may seem very similar at first glance, especially given

the similarities in the definitions of permanents and determinants, they are extremely

different when trying to actually compute these scattering amplitudes. Indeed, while

the determinant of an n dimensional matrix can be efficiently computed, the same is

in general not true for permanents. This is exactly what makes the BosonSampling

problem interesting, and will be described in detail in the next sections.

In conclusion, we can now write down the unitary matrix describing the evolution

of the many-body states, that is, the matrix Uα,β(m, n, U), with α, β ∈ Gn,m, whose

elements contain the permanents (or the determinants, in the case of fermions) of the

corresponding matrix given by eq. (2.18):

Uα,β(m, n, U) ≡

1

µ(α)µ(β)

perm(U[α|β]), α, β ∈ Gn,m. (2.20)

The dependence of U on n, m, and U will often be omitted when clear from the context.

Example 5. Consider the 3×3 unitary matrix Ui,j ≡ ui,j, injected with 2-photon

input states. The resulting many-boson scattering matrix is:

U(3, 2, U) =

u2,3u3,2 + u2,2u3,3 u2,3u3,1 + u2,1u3,3 u2,2u3,1 + u2,1u3,2

√

2u2,3u3,3

√

2u2,2u3,2

√

2u2,1u3,1

u1,3u3,2 + u1,2u3,3 u1,3u3,1 + u1,1u3,3 u1,2u3,1 + u1,1u3,2

√

2u1,3u3,3

√

2u1,2u3,2

√

2u1,1u3,1

u1,3u2,2 + u1,2u2,3 u1,3u2,1 + u1,1u2,3 u1,2u2,1 + u1,1u2,2

√

2u1,3u2,3

√

2u1,2u2,2

√

2u1,1u2,1√

2u3,2u3,3

√

2u3,1u3,3

√

2u3,1u3,2 u2

3,3 u2

3,2 u2

3,1√

2u2,2u2,3

√

2u2,1u2,3

√

2u2,1u2,2 u2

2,3 u2

2,2 u2

2,1√

2u1,2u1,3

√

2u1,1u1,3

√

2u1,1u1,2 u2

1,3 u2

1,2 u2

1,1

2.2 Counting many-body states

Another interesting property of many-body states is their number. Unlike classical

states, it is not meaningful to assign a state to the single particles of a quantum many-

body state. A quantum state is instead described only giving the list of modes occupied

30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-30-320.jpg)

![2.3.4 Single-photon sources

An ideal single-photon source [42, 43, 44] would be one that

1. Is deterministic (or “on demand”), meaning that it can emit a single photon at any

arbitrary time defined by the user,

2. Has a 100% probability of emitting a single photon and a 0% probability of multiple-

photon emission,

3. Subsequently emitted photons are indistinguishable,

4. The repetition rate is arbitrarily fast.

Given however that no real-world photon source satisfies all of these specifications,

the deviations from the ideal characteristics must be considered when designing exper-

iments.

Single-photon sources are broadly classified into deterministic and probabilistic.

Among the implementations of the former are those based on color centers [45, 46, 47],

quantum dots [48, 49, 50], single atoms [51], single ions [52], single molecules [53],

and atomic ensembles [54], all of which can to some degree emit single photons “on

demand”. On the other hand are the probabilistic single-photon sources. These generally

rely on photons created in pairs via parametric downconversion in bulk crystals and

waveguides, and four-wave mixing in optical fibers. While these sources are probabilistic

- and therefore it is not possible to know exactly when a photon has been emitted -

because the photons are created in pairs, one of the emitted photons can be used to

herald the creation of the other.

While the distinction between deterministic and probabilistic sources is clear in the

abstract, this distinction blurs in practice. This due to the unavoidable experimental

errors that make also “theoretically deterministic sources” be probabilistic in practice.

Although many applications, especially those in the field of quantum-information

science, require an on-demand source of single photons, probabilistic single-photon

sources remain a fundamental tool, and are widely used in many quantum optics

experiments.

Spontaneous parametric downconversion (SPDC) is an important process in quan-

tum optics, typically exploited to generate entangled photon pairs, or heralded single

photons. This is achieved using a nonlinear crystal - that is, a medium in which the

dielectric polarization responds nonlinearly to the electric field - which converts the

photons of a pump beam into pairs of photons of lower energy. A simple model of the

interaction Hamiltonian in such a crystal is

HI ∼ χ(2)

ˆapˆa†

sˆa†

i + hermitian conjugate, (2.36)

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-37-320.jpg)

![with |pi = (ˆa†

i )p

/

√

p!, and 0 ≤ g < 1 an appropriate parameter determining the ratio

of generated photons and dependent, among other things, on the strength of the pump

beam. Typically, g 1, so that the probability of generating many photons is low. For

instance, in typical conditions g ∼ 0.1 and the probability of generating a state of the

form |21 |22 is lower of a factor ∼ 102

than the probability of producing a single pair

|11 |12 .

The main advantages of SPDC sources are the high photon indistinguishability, the

collection efficiency, and relatively simple experimental setups. This technique, however,

suffers from two drawbacks. First, since the nonlinear process is nondeterministic, so is

the photon generation, even though it can be heralded. Second, the laser pump power,

and hence the source’s brilliance, has to be kept low to prevent undesired higher-order

terms in the photon generation process.

Figure 2.6: Representation of type II downconversion. The pump beam (red) impinges on the nonlinear

crystal, generating, due to birefringence effects, photons along two cones. On the upper ordinary cone

(orange), the generated photons are horizontally polarized, while on the lower extraordinary cone (green)

the generated photons are vertically aligned. Postselecting on the two intersections of these cones (blue

dots), a pair of polarization-entangled photons is obtained.

2.3.5 Single-photon detectors

Roughly speaking, single-photon detectors are devices which convert single photons

into an electrical signal of some sort [42]. Quantum information science is one of the

field currently driving much of the research toward improved single-photon-detector

technology. For example, many quantum communication protocols rely heavily on

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-39-320.jpg)

![detector properties such as detection efficiency.

An ideal single-photon detector [42] would require the following characteristics:

1. The detection efficiency - that is, the probability that a photon incident upon the

detector is successfully detected - is 100%,

2. The dark-count rate - that is, the rate of detector output pulses in the absence of

any incident photons - is zero,

3. The dead time - that is, the time after a photon-detection event during which the

detector is incapable of detecting another photon - is zero,

4. The timing jitter - that is, the variation from event to event in the delay between

the input of the optical signal and the output of the electrical signal - is zero.

Additionally, an ideal single-photon detector would also be able to count the number of

photons in an incident pulse. Detectors able to do this are referred to as photon-counting,

or photon-number resolving, detectors. However, non-photon-number-resolving detec-

tors, which can only distinguish between zero photons and more than zero photons,

are the most commonly used. Indeed, while detecting a single photon is a difficult task,

discriminating the number of incident photons is even more difficult. Examples of non-

photon-number-resolving single-photon detector technologies include single-photon

avalanche photodiodes [55], quantum dots [56], superconducting nanowires [57], and

up-conversion detectors [58, 59, 60].

2.4 Hong-Ou-Mandel effect

The differences between bosons and fermions are not only in the different numbers of

microstates. Their statistical behaviour can differ significantly, as well as be significantly

different from the behaviour of distinguishable particles.

Bosons, roughly speaking, tend to occupy the same state more often than classical

particles, or fermions, do. This behaviour, referred to as bosonic bunching, has been

verified in numerous experimental circumstances, including fundamental ones like

Bose-Einstein condensation [61, 62, 63]. In the context of optical experiments, the most

known effects arising from the symmetric nature of the Bose-Einstein statistics is the

Hong-Ou-Mandel (HOM) effect [64].

In the original experiment, two photons are sent simultaneously through the two

input ports of a symmetric beam splitter. Since no interaction between the two photons

takes place, one would expect no correlation between the detection events at the two

output ports. Instead, the photons are always seen either both on the first output mode,

or both on the second output mode.

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-40-320.jpg)

![+ − +

Figure 2.7: Pictorial representation of the suppression of non-bunched events, when two indistinguish-

able bosons evolve through a symmetric beam splitter. Each of the four images represent a possible

evolution of the bosons, with all of them interfering with each other. The two events which would result

in one boson per output port turn out to interfere destructively (note the minus sign), and are suppressed.

This effect is a direct consequence of the quantum interference between the possible

ways two-photon states can evolve. A pictorial representation of this is given in fig. 2.7:

when the photons are injected into two different ports of a symmetric beam splitter,

the scattering amplitudes corresponding to the output photons being in two different

modes interfere destructively.

We can derive this result applying eq. (2.33) to the two-photon input state |11, 12 =

ˆa†

1ˆa†

2 |0 :

|11, 12 = ˆa†

1ˆa†

2 |0 →

1

√

2

ˆb†

1 − iˆb†

2

1

√

2

−iˆb†

1 + ˆb†

2 |0

=

1

2

−i(ˆb†

1)2

+ ˆb†

1

ˆb†

2 − ˆb†

2

ˆb†

1 − i(ˆb†

2)2

=

−i

2

(ˆb†

1)2

+ (ˆb†

2)2

|0 =

−i

√

2

(|21 + |22 ) ,

(2.41)

where in the last steps we used the rules given in eq. (2.3), and in particular the

commutativity of the bosonic creation operators, which implies that ˆb†

1

ˆb†

2 = ˆb†

2

ˆb†

1 (see

also fig. 2.7 for a pictorial representation of how the suppression of non-bunched events

arises). We thus conclude that when two indistinguishable photons enter a symmetric

beam splitter one in each mode, they always come out in the same mode.

This property of photons (or, more generally, of bosons) is highly non-classical, and

is a notable example of how interesting effects can arise when dealing with many-body

quantum states.

In a real world experiment, the two input photons will never be perfectly indistin-

guishable, though. A more careful analysis, taking into account the potentially different

times at which the photons reach the beam splitter, as well as the coherence time of

each photon wave packet, predicts a smooth transition from the classical behaviour to

the antibunching effect described above [65].

In the general case of partially distinguishable particles, the probability PT (s, x) of

detecting an output state s in an HOM experiment with a time delay quantified by x,

becomes an average of the probability PB for bosons and the probability PD assigned

to distinguishable particles, weighted by two factors |c1|2

and |c2|2

which depend on

41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-41-320.jpg)

![the relative time delay:

PT (s, x) = |c1(x)|2

PB(s) + |c2(x)|2

PD(s). (2.42)

In a typical experimental scenario, with the incoming photons having a Gaussian

frequency distribution around the central frequency, PT (s, x) also has a gaussian profile

[65], as shown in a typical case in fig. 2.8.

In the case of fully distinguishable particles, where PT = PD, no interaction

occurs and the output events of the single photons are not correlated. There are

two possible classical configurations of two photons in the output MOL (1, 1), and

one configuration for both (2, 0) and (0, 2). It follows that PD((1, 1)) = 2/4 and

PD((2, 0)) = PD((0, 2)) = 1/4, as shown in fig. 2.8 for x ≈ ±400µm. On the other

hand, when the particles are fully indistinguishable, PT = PB. The probability of the

various outcomes is now given by eq. (2.41). The output (1, 1) is thus suppressed, while

PB((2, 0)) = PB((0, 2)) = 1/2, as shown in fig. 2.8 for x = 0.

Figure 2.8: Transition to indistinguishability in a HOM experiment. Changing the time delay between

the two input photons a dip in the number of measured output coincidences is seen, corresponding

to the time delay (or, equivalently, the path delay) making the photons indistinguishable. The blue

line is the probability of detecting two photons in one of the two output ports, that is, PT ((2, 0), x) or

equivalently PT ((0, 2), x). The red line is the probability PT ((1, 1), x) of detecting the two photons in

the two different output ports. As expected, the red plot shows a peak corresponding to the antibunching

effect arising when the particles are indistinguishable, while the blue plot show the HOM explained above.

42](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-42-320.jpg)

![Chapter 3

BosonSampling

In this chapter we discuss various aspects of the BosonSampling computational prob-

lem. In section 3.1 the problem of experimentally assessing quantum supremacy is

discussed, in order to appreciate the importance of BosonSampling in the modern

research context. Section 3.2 follows with the description of what the BosonSampling

computational problem is, and its advantages in obtaining experimental evidences

of quantum supremacy. In section 3.3 some issues related to the scalability of boson

sampling implementations are described. The chapter closes with a description of

scattershot boson sampling in section 3.4, as an alternative architecture to scale boson

sampling implementations to higher numbers of photons.

3.1 Importance of BosonSampling

It is currently believed that many quantum mechanical systems cannot be efficiently

simulated with a classical computer [1]. This implies that a quantum device is, to the

best of our knowledge, able to solve problems de facto beyond the capabilities of classical

computers. Exploiting this quantum advantage requires however an high degree of

control over the quantum system, not yet manageable with state of the art technology.

In particular, a post-classical computation with a universal quantum computer will

require an high degree of control of a large number of qubits, and this implies that an

experimental evidence of quantum supremacy [3] with an universal quantum computer

will likely require many years. A notable example is given by the large gap between the

number of qubits that can currently be coherently controlled (∼10), and the number

of qubits required for a calculation such as prime factorization, on a scale that would

challenge classical computers (∼106

). Consequently, there is considerable interest in

non-universal quantum computers and quantum simulators that, while able to only

solve specific problems, might be significantly easier to be implemented experimentally.

Such devices could give the first experimental demonstration of the power of quantum

43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-43-320.jpg)

![devices over classical computers, and potentially lead to technologically significant

applications.

Moreover, in the context of searching for experimental evidence of quantum supremacy,

the technological difficulties are not the only issue. To show this, we will consider as an

example Shor’s quantum algorithm [30] to efficiently factorize integer numbers. Even if

we were to get past the technological difficulties of implementing Shor’s algorithm with

sufficiently many qubits, it could be easily argued that such an achievement would not

be a conclusive evidence that quantum mechanics allows post-classical computations.

This because we do not have to date a mathematically sound proof that there cannot be a

classical algorithm to efficiently factorize integers. In the language of complexity theory,

this corresponds to the fact that we do not have a proof that Factoring is not in P,

even though this is believed enough to base modern cryptography is based on this

conjecture. More generally, before 2010, there were no instances of problems efficiently

solved by quantum computers, which were proved to not be efficiently solvable with

classical ones.

This changed when, in 2010, Aaronson and Arkhipov (AA) proposed [8] the Boson-

Sampling problem as a way to obtain an easier experimental evidence of quantum

supremacy. BosonSampling is a computational problem that, while hard to solve for

a classical computer, is efficiently solved by a special-purpose quantum device. AA

showed that BosonSampling is naturally implemented using only linear optical ele-

ments, in a photonic platform named a boson sampler. The experimental realization

of a boson sampler, while still challenging with present-day technologies, requires

much less experimental efforts with respect to those required to build a universal

quantum computer. In fact, the AA scheme requires only linear optical elements and

photon-counting detectors, as opposite to, for example, the Knill, Laflamme & Milburn

approach [7, 40] for universal linear optics quantum computing, which requires among

other things an extremely fast feedback control of the detectors.

44](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-44-320.jpg)

![Figure 3.1: Galton board: n identical balls are dropped one by one from the upper corner, and are

randomly scattered into the lower slots. The quantum generalization of this classical “rudimentary

computer” leads to the idea of BosonSampling. Credits: Nicolò Spagnolo.

3.2 The BosonSampling computational problem

Consider the following linear optical experiment: the n-photon state |rAA given by

|rAA ≡ |11, . . . , 1n, 0n+1, . . . , 0m ≡ ˆa†

1 . . . ˆa†

n |01, . . . , 0m , (3.1)

is injected into a passive linear optics network, which implements a unitary map on

the creation operators:

ˆa†

k → ˆUˆb†

k

ˆU†

=

m

j=1

Uk,j

ˆb†

j. (3.2)

with U an Haar-random m×m complex unitary matrix. The evolution induced on

|rAA is

|rAA →

s∈Fn,m

A(r → s, U) |s , (3.3)

where the sum is extended over all many-boson states of n particles into m modes, and

the scattering amplitudes A are, as shown in eq. (2.18), proportional to the permanents

of n×n matrices. AA argued that, for m n, the output of such an apparatus cannot

be efficiently predicted by a classical computer, neither exactly nor approximately [8].

This was rigorously proved in the exact case. The problem of approximately sampling

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-45-320.jpg)

![from the output probability distribution of a boson sampling apparatus depends instead

on a series of conjectures, for which strong supporting evidence was provided [8].

This problem, which amounts to that of being able to sample from the output proba-

bility distribution given in eq. (2.18), is referred to as the BosonSampling computational

problem. The constraint m n is essential for the hardness result, as otherwise

semi-classical methods become efficient [66, 67].

Roughly speaking, a boson sampling apparatus is a “quantum version” of a Galton

board. A Galton board, named after the English scientist Sir Francis Galton, is an

upright board with evenly spaced pegs into its upper half, and a number of evenly-

spaced rectangular slots in the lower half (see fig. 3.1). This setup can be imagined to

be a rudimentary “computer”, where n identical balls are dropped one by one from

the upper corner, and are randomly scattered into the lower slots. In the quantum

mechanical version, the n balls are indistinguishable bosons “dropped” simultaneously,

and each peg a unitary transformation, typically implemented as a set of beam splitters

and phase shifters.

More precisely, BosonSampling consists in producing a fair sample of the output

probability distribution P(s |U, rAA) ≡ |A(r → s, U)|2

, where s is an output state of

the n bosons, and rAA the above mentioned input state. The unitary ˆU and the input

state rAA are the input of the BosonSampling problem, while a number of output states

sampled from the correct probability distribution are its solution (see fig. 3.2).

46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-46-320.jpg)

![Figure 3.2: Conceptual boson sampling apparatus. (a) The input of the BosonSampling problem is

the input many-photon state (in figure the state |0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0 ), and a suitably chosen unitary U.

The output is a number of outcomes picked according to the bosonic output probability distribution (in

figure, two examples of such states are provided, with MOLs 101000100 and 110000100). Colleting enough

such events allows to reconstruct the probability distribution. This, however, requires an exponentially

increasing (in n) number of events. (b) Injecting an m-mode unitary with n indistinguishable photons,

the output state is a weighted superposition of all possible outcomes. Measuring in which modes the

photons ended up results in the collapsing of this superposition. The probability of finding the photons

in a certain configuration is given by eq. (3.4). Credits: [10].

47](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-47-320.jpg)

![from the correct probability distribution would theoretically be enough to achieve

a post-classical computation, though possibly making it harder to experimentally

verify.

The hardness of the BosonSampling problem can be traced back to the #P-hardness

of computing the permanent of a generic complex-valued matrix. Indeed, as shown in

eq. (2.18), the probability P(r → s, U) of an input r evolving into s, is proportional to

the permanent of the matrix U[R|S] (recalling definition 3):

P(r → s, U) = |A(r → s, U)|2

=

1

µ(R)µ(S)

|perm(U[R|S])|2

. (3.4)

Computing the permanent of a n×n matrix with the fastest known classical algorithms

[41, 68] requires a number of operations of the order O(n2n

). This means that, for

example, computing the permanent of a 30×30 complex matrix, corresponding to a

single scattering amplitude for a 30-photon state, requires a number of operations of the

order of ∼ 1010

. If the average time required by a classical computer to perform a single

operation is of the order ∼ 107

, the computation of one such scattering amplitude

will require ∼ 10 minutes. While still clearly manageable by a classical computer,

this already shows the potential advantages of a boson sampling apparatus: if the

experimental problems related to coherently evolve 30 indistinguishable photons inside

an interferometer were to be solved, this would allow to sample from the probability

distribution given by eq. (3.4) without actually knowing the probabilities itselves.

AA demonstrated that, should boson sampling be classically easy to solve, this would

have very strong and undesied consequences in computational complexity theory, and

therefore it is most probable that boson sampling is not classically easy to solve.

It is worth stressing that the BosonSampling problem is not that of finding the per-

manents in eq. (2.18), but only that of sampling from the related probability distribution.

In fact, not even a boson sampler is able to efficiently compute these scattering probabil-

ities. This is due to the fact that, to reconstruct a probability distribution spanning over

a number M of events, roughly speaking, the number of samples is required to be at

least of the order of M. But, as shown in eqs. (2.22) and (2.23), M scales exponentially

with n, implying that the number of experimental samples required to reconstruct the

probability distribution becomes exceedingly large very soon. In figs. 3.3 and 3.4 is

shown that, if the number of samples is not large enough, the reconstructed probability

distribution is different from the real one. In fact, generally speaking, there are strong

arguments against the possibility to compute the permanents of complex-valued matri-

ces by means of quantum experiments [69], although attempts have been reported in

this direction [70].

49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-49-320.jpg)

![The complexity of BosonSampling makes it an extremely valuable candidate to gain

experimental evidences of the supremacy of quantum devices over classical computers.

Indeed, it presents several advantages in this regard over, for example, Factoring,

which is the paradigmatic problem that would allow quantum computers to perform a

post-classical computation:

1. The BosonSampling problem is even harder than Factoring, being related to

the #P-hard complexity class, and believed to not be in NP.

2. A boson sampler requires significantly less resources to be implemented than a

universal quantum computer. In particular, it does not require adaptive or feed-

forward mechanisms, nor fault-tolerance methods. This relatively simple design

has already prompted a number of small-scale implementations of increasing

complexity [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 25, 71].

AA suggested [8] that a 400-modes interferometer fed with 20 single photons

is already at the boundary of the simulation powers of present-day classical

computers. While in this regime it would still be possible to carry out a classical

simulation, the quantum device should be able to perform the sampling task faster

than the classical computer.

3. The theoretical evidence of the hardness of BosonSampling is stronger than that

of factoring integers: while in the former case the result only relies on a small

number of conjectures regarding the hardness of some problems [8], in the latter

case there is no compelling evidence for Factoring to not be in P. While known to

be in BQP, Factoring is only believed to be in NP, and strongly believed to not

be in NP-hard.

While the hardness of Factoring is strong enough to build modern cryptography,

it could also happen that a polynomial-time algorithm will be discovered showing

that Factoring is in P as, basically, the sole evidence for its hardness is the fact

that no efficient classical algorithm is yet known.

3.3 Scaling experimental boson sampling implemen-

tations

The hardness of BosonSampling has another potentially important consequence: it

could provide the first experimental evidence against the ECT [8]. This point, however,

is still subject to some debate [67, 72, 73], due to the somewhat informal nature of

the ECT itself. Indeed, the ECT is not a mathematical statement, but a statement about

how the physical world behaves, in a certain asymptotic limit. Because of this it is

51](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/51b2159f-4e1f-48f3-91cc-51dca4e8cf7b-160331120712/85/thesis-51-320.jpg)

![somewhat ill-defined what exactly would be “enough experimental evidence” to “prove”

or “disprove” such a statement.

While AA argued for the hardness of both the exact and approximate BosonSam-

pling problems, they did not take into account other forms of experimental imperfec-

tions.

More precisely, AA showed that even attempting to estimate the output probability

distribution of a boson-sampler is likely computationally hard, as long as the probability

P of each input state being correctly produced by the sources scales as P > 1/ poly(n),

that is, does not vanish faster than the inverse of a polynomial in n [8]. Further evidence

that even lossy systems or systems with mode mismatch are likely to be classically hard

to solve was later given [74].

Another source of errors which could potentially undermine the scalability of boson

sampling are the unavoidable circuit imperfections, especially taking into account

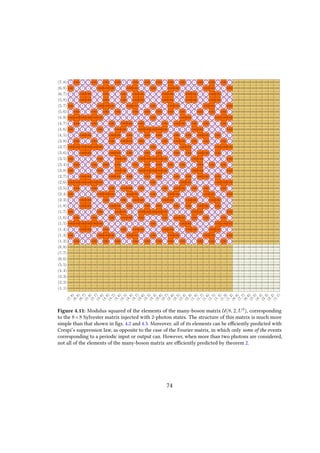

the fact that a boson sampler cannot likely implement fault-tolerant mechanisms [8].