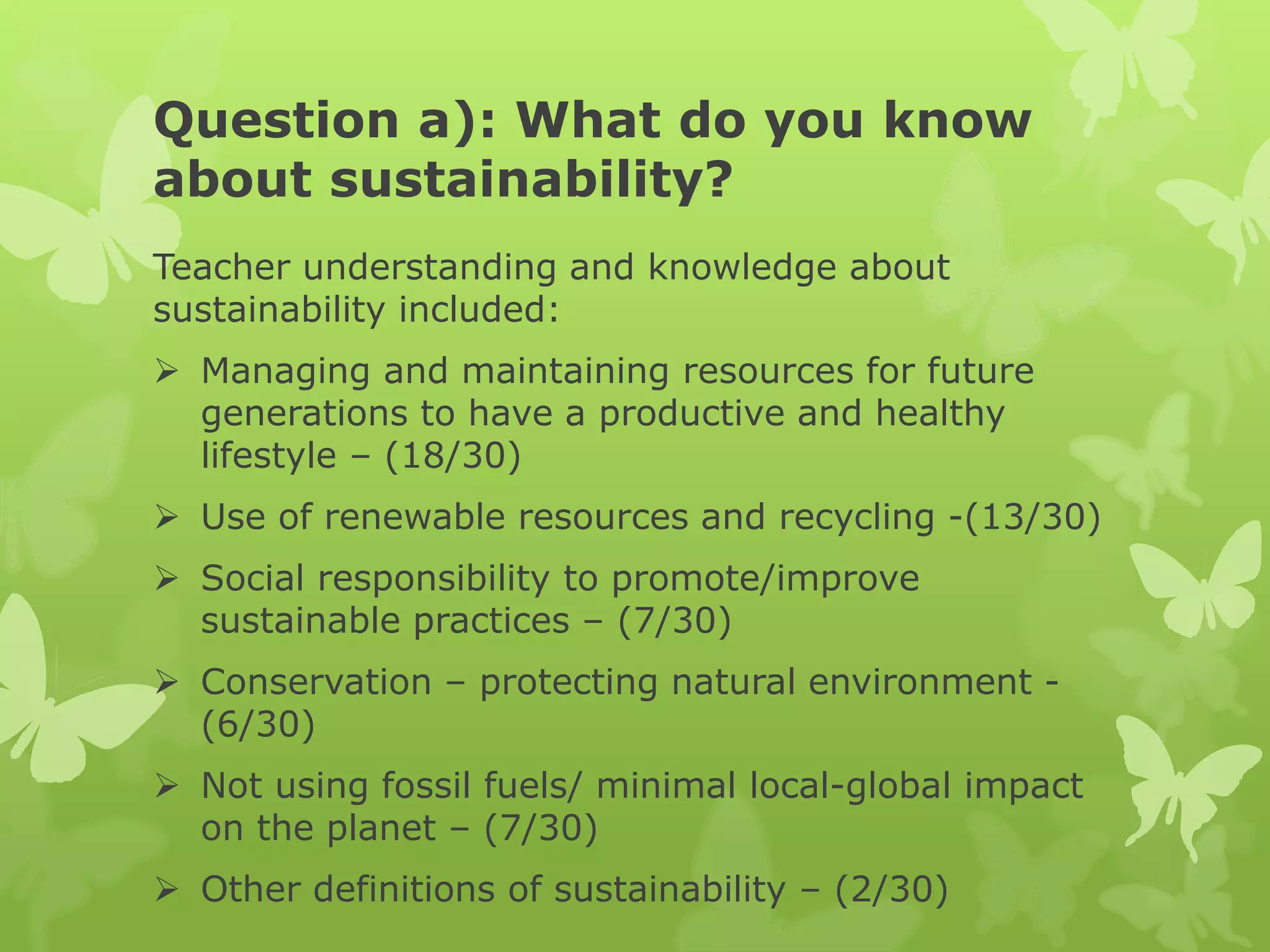

This document summarizes a case study examining how teachers at a primary and secondary school in Melbourne, Australia incorporate sustainability into their curricula and teaching. Interviews were conducted with 30 teachers to understand their knowledge of sustainability, views on its role in curricula, attitudes towards teaching it, current practices, and resource use. Key findings include that teachers see sustainability as managing resources for future generations and integrating it across subjects, but feel additional support and training is needed. The study aims to help better prepare teachers and students for environmental and social challenges.