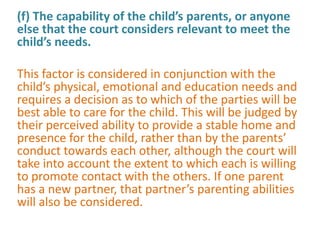

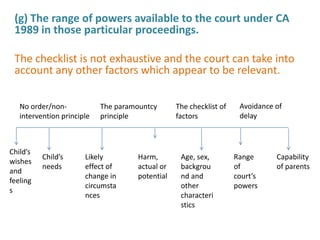

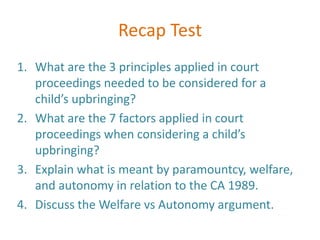

The document discusses the Children Act 1989 and the principles and factors courts consider when making decisions about a child's upbringing. The three principles are: 1) the paramountcy principle where the child's welfare is the top priority; 2) the no order/non-intervention principle where the court only makes orders if necessary; and 3) avoiding delay in decisions. The seven factors courts examine are the child's wishes, needs, potential changes, harm risks, characteristics, parents' capabilities, and available court powers. There is a debate between prioritizing the child's welfare versus autonomy as their rights increase. Overall, the document outlines the framework courts

![The child’s autonomy

Key case?

Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech AHA [1986] AC 112:

M sought assurance that her daughters could not be given

contraceptive advice without her consent – AHA refused -

, Mrs G sought declaration that the advice was wrong and

infringed her rights as a parent. She claimed that the right to

decide whether they could or could not receive such advice

(like the right to consent to medical treatment) was part of

her “parental rights”.

What do you think? Do you think that Mrs G was right? Did

this infringe her parental rights? What about the child’s

rights?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/childrenactlecture2-120420165403-phpapp02/85/The-Principles-and-the-Factors-8-320.jpg)

![Re A (Minors)(Conjoined Twins: Medical Treatment)

[2001] 2 WLR 480 CA.

Take the above medical case:

Twins were born joined at the abdomen. The heart of the stronger one was keeping

the weaker one alive. The parents were in agreement – they felt an operation to

separate the twins should not take place as the weaker twin would die. The hospital

thought that was wrong – the weaker twin had no real prospect of life and would

endanger the other one – if the operation did not take place both were likely to die

within months – if it did take place the weaker one would die immediately but the

stronger one had a chance of life - so the hospital felt the operation should take

place, even though the weaker twin would then die. The hospital applied to the court.

What do you think is the paramount issue here?

Ward LJ said parental rights and powers “exist for the performance of their duties and

responsibilities to the child and must be exercised in the best interests of the child.”

Parents’ wishes are a weighty factor but “parental right is, however, subordinate to

welfare”.

Take note of the concept of “welfare”. We will look at that more closely, in

conjunction with the idea of “rights”.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/childrenactlecture2-120420165403-phpapp02/85/The-Principles-and-the-Factors-11-320.jpg)

![(a) The paramountcy principle

It has been questioned whether the paramountcy

principle is compatible with Art 8 ECHR (right to life)

which, read strictly, would seem to require a

balancing of the interests of all the members of the

family (adults and children) when their interests

conflict. The English courts have taken the view that

there is no conflict between the two (RE B [2002])

and the ECHR have stated that the welfare of the

child may justify an interference with parental

rights (Johansen v Norway [1997]). ***](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/childrenactlecture2-120420165403-phpapp02/85/The-Principles-and-the-Factors-12-320.jpg)

![“Welfare”, “Best Interests” and

“Rights”

CA 1989 s1(1) says that the child’s “welfare” is “paramount” in

deciding any question in relation to the child (the “welfare

principle”)

“Paramount” means it overrides all other considerations

HL in J v C [1970] AC 668 held that “first and paramount”

meant that the child’s welfare is the sole consideration. As the

word “first” is otiose this is the settled understanding of

“paramount”.

Per L MacDermott it means “more than that the child’s

welfare is to be treated as the top item on a list….*it is+ the

paramount consideration because it rules upon or determines

the course to be followed.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/childrenactlecture2-120420165403-phpapp02/85/The-Principles-and-the-Factors-13-320.jpg)

![J v C [1970] AC 668

Child born in 1958 in England, of Spanish parents.

M ill so child went to foster parents for 1 year. Then

went to Spain with parents for 17 months. Then

returned to the foster parents. Made a ward of

court and decision in 1965 that he remain with the

foster parents. When child was 10 the

parents, who were now settled, asked for custody.

The court felt a move to Spain now would be

harmful. Even though the parents were

“unimpeachable” and so normally would have their

own children, their wishes were to be looked at in

the light of the child’s welfare.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/childrenactlecture2-120420165403-phpapp02/85/The-Principles-and-the-Factors-14-320.jpg)

![The FACTORS applied in court

proceedings

S.1(3) CA 1989 contains a checklist of the factors that the court should take

into account in certain proceedings involving children, including those for a

s.8 order (residence, contact, prohibited steps, and specific issue orders).

The factors include the following:

(a) The wishes and feelings of the child concerned, in the light of his age and

understanding.

The views of the children must be taken into account in light of their age and

maturity. Inevitably, the older a child, the more likely it is that his views will

be taken into account and even determine the issue. In Re S (Children’s

Views) [2002] the court refused to make an order for contact relating to two

children aged 14 and 16, who stated that they did not wish to see their father.

What key case can you think of that relates to the child’s autonomy?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/childrenactlecture2-120420165403-phpapp02/85/The-Principles-and-the-Factors-18-320.jpg)

![(e) The child’s age, sex, background and any

characteristics which the court considers relevant.

This allows the court to focus on issues such as race

and religion as well as matters of day-to-day care. If

one parent adopts an unorthodox lifestyle, then this

will be taken into account. The court will not decide

between two competing lifestyles but will focus on

the effect, if any, they may have on the child (e.g.

estrangement from other members of the family, or

limited or no resort to medical treatment: M v H

(Education Welfare) [2008].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/childrenactlecture2-120420165403-phpapp02/85/The-Principles-and-the-Factors-22-320.jpg)

![M v H (Education Welfare) [2008]

A specific issue arose under a joint residence arrangement as

to whether a young child should be educated in England and

therefore spend the majority of his time living with his father

or in Germany with his mother who has become a Jehovah’s

Witness. The held the mother’s beliefs and practices were

factors which favoured the child going to school in England

particularly in relation to parties and Christmas and in terms

of the range of social relationships open to the child.

Although there is no precise rules, the courts usually decide

that young children are best protected by staying with their

mother. It is not unusual for older children to be allowed to

live with their father.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/childrenactlecture2-120420165403-phpapp02/85/The-Principles-and-the-Factors-23-320.jpg)