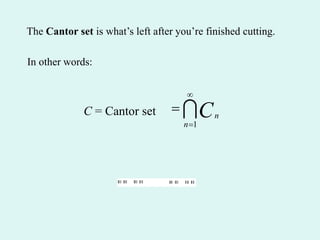

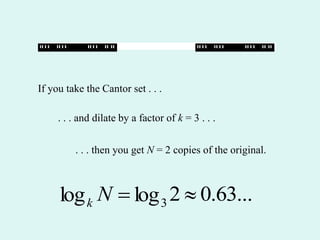

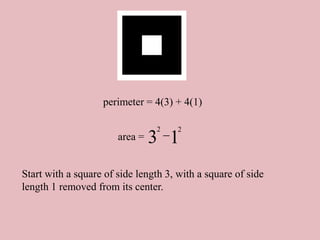

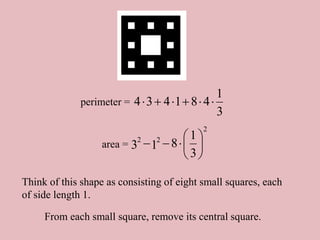

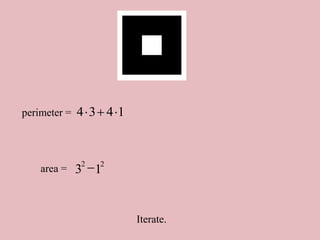

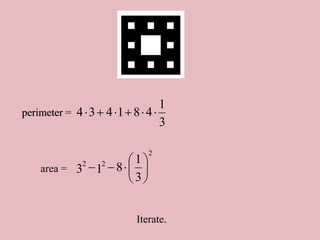

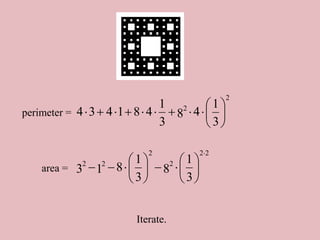

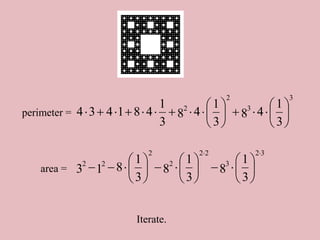

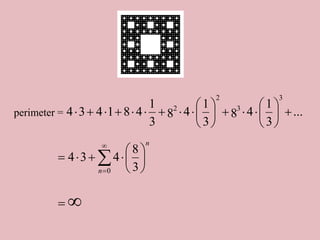

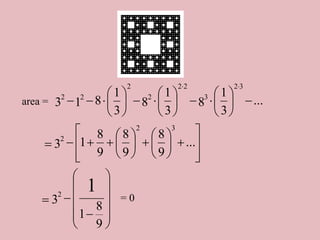

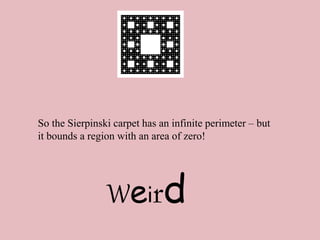

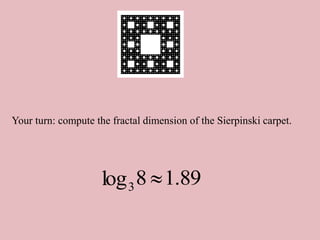

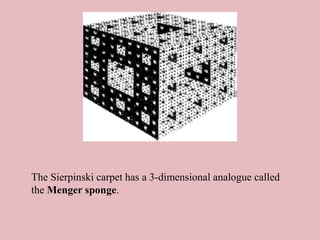

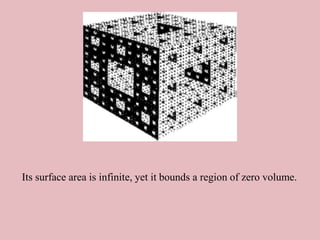

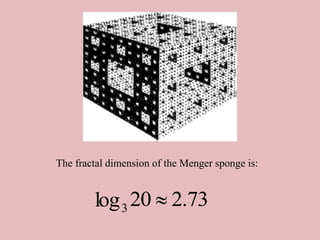

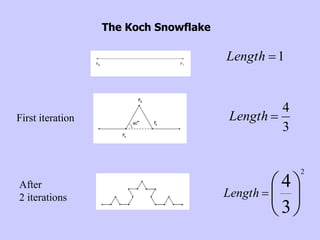

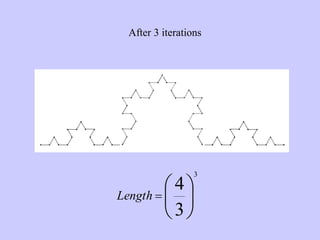

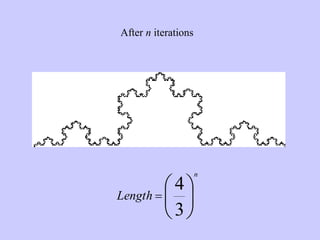

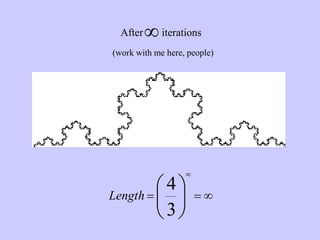

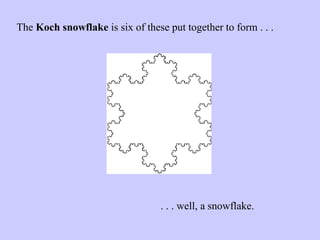

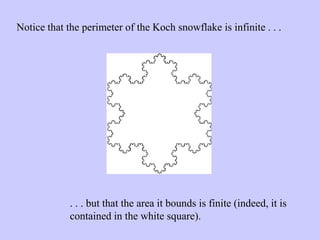

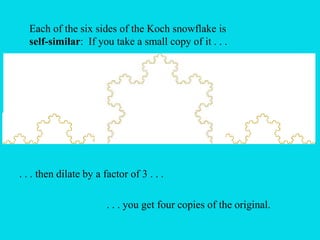

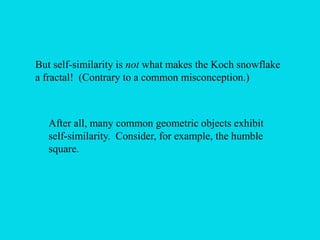

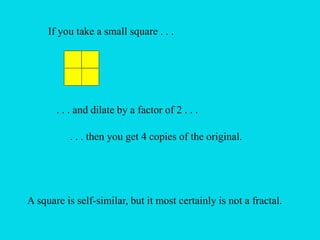

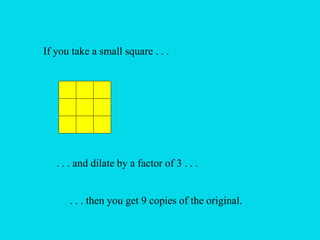

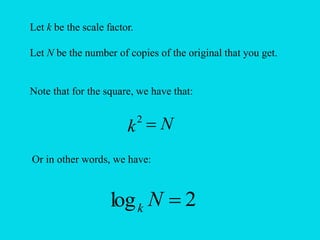

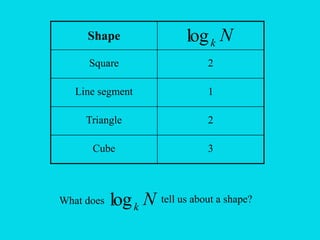

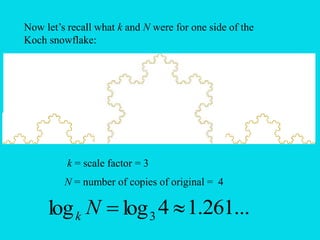

The document discusses the Koch snowflake, a fractal shape with an infinite perimeter but finite area, and its applications in technology such as antenna designs. It also covers the concept of fractals, differentiating self-similar shapes from other geometric forms, and introduces the Cantor set and Sierpinski carpet, both exhibiting counterintuitive properties regarding dimensions and areas. The document concludes by noting the infinite perimeter and zero area characteristics of these fractals.

![Start with a line segment of length 1.

Now cut away the middle third.

Then cut away the middle third of each remaining piece.

]

1

,

0

[

1

C

Iterate.

]

1

,

3

2

[

]

3

1

,

0

[

2

C

. . . . . .

]

1

,

9

8

[

]

9

7

,

3

2

[

]

3

1

,

9

2

[

]

9

1

,

0

[

3

C

]

1

,

3

1

3

[

]

3

2

3

,

3

2

[

...

]

3

1

,

3

2

[

]

3

1

,

0

[ 1

2

1

2

2

2

1

1 n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

C

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fractals2-240302071154-b8af468d/85/The-Koch-Snowflake-SELF-SIMILAR-CONCEPTS-26-320.jpg)