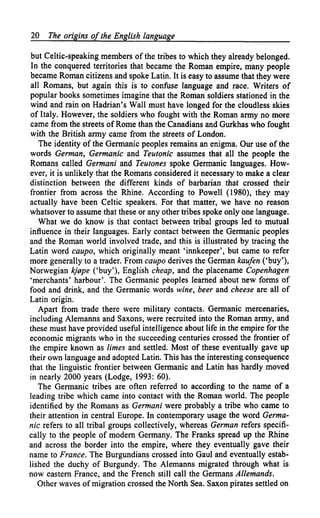

This document discusses the origins and development of the English language. It begins by examining the linguistic geography of Europe prior to the origins of English, noting that western Europe was broadly divided into Celtic-speaking south and Germanic-speaking north, overlaid by the spread of Latin from Rome. It then focuses on the specific linguistic situation in Britain, where Celtic languages were spoken until the 5th century arrival of Anglo-Saxon Germanic tribes. These early dialects eventually developed into the four main dialects of Old English: Northumbrian, Mercian, West Saxon, and Kentish, which correlated largely with the political kingdoms and boundaries at the time.

![Early English 23

Northumbria is still reflected in the name of the Mersey ('boundary river').

In the south, Wessex stretched from the Tamar in the west to the bound-

aries of Kent in the east.

2.3 Early English

Any detailed knowledge we have of early English necessarily comes from

the first written records. In other words we have to make inferences about

the spoken language from the written language. This is made difficult by

the different patterns of contact. Whereas spoken English was interacting

with Celtic in the context of the emerging kingdoms, written English was

interacting with Latin as the international language of Christendom.

Early English dialects

There was no such thing at this time as a Standard English language in our

modern sense. Not only did the original settlers come from many different

tribes, they also arrived over a long period of time, so that there must have

been considerable dialect variety in the early kingdoms. As groups

achieved some local dominance, their speech was accorded prestige, and

the prestigious forms spread over the territory that they dominated. In some

cases the immigrants took control of existing Celtic kingdoms, for example

Northumbria subsumed the old kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira (Higham,

1986). Here there would already be a communications infrastructure which

would enable the prestigious forms to spread. Within their borders, there

would thus be a general tendency towards homogeneity in speech. The

evidence of the earliest written records suggests a rough correlation

between dialects and kingdoms, and the dialects of Anglo-Saxon are con-

ventionally classified by kingdom: Northumbrian, Mercian, West Saxon

and Kentish (see map 1). The northern dialects, Northumbrian and Mer-

cian, are usually grouped together under the name Anglian. The pattern of

change which was established at this period survived until the introduction

of mass education in the nineteenth century.

Subsequent development of English dialects can in some cases be traced to

shifts in political boundaries. The new Scottish border (see section 3.1), for

example, cut the people of the Lowlands off from the rest of Northumbria,

with the result that the dialects on either side of the border began to change in

different directions. The political boundary between Mercia and Northum-

bria, for instance, disappeared over 1000 years ago, and yet there are still

marked differences in speech north and south of the Mersey. In south-east

Lancashire, a consonantal [r] can still be heard in local speech in words such

as learn, square, but this is not heard a few miles away in Cheshire.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/texto-theoriginsoftheenglishlanguage-111124200150-phpapp01/85/Text-The-origins-of-the-English-language-6-320.jpg)

![Early English 25

Traces of the old dialect of Kent survive in modern Standard English.

There are indications that Kent was settled by some homogeneous tribal

group, possibly Jutes or Frisians, and so Kentish may have had marked

differences from the earliest times. A distinctive feature of Kentish con-

cerned the pronunciation of the vowel sound written <y>' in early English

spelling, which elsewhere must have been similar to the French vowel of tu

[ty] ('you'), or German ktihl [ky:l] ('cool'). In Kent the corresponding

vowel was often written <e>. For example, a word meaning 'give' was

syllan in Wessex and sellan in Kent; it is of course from the Kentish form

that we get the modern form sell. After the Norman conquest the [y] sound

was spelt <u>, and this is retained in the modern spelling of the word bury;

the pronunciation of this word, however, has the vowel sound [e], and was

originally a Kentish form.

When England finally became a single kingdom, innovations would

spread across the whole of the country, and begin to cross old borders.

Eventually this created a situation in which some features of language are

general and others localized. The general features are interesting because

they form the nucleus of the later standard language. This point is worth

emphasizing, because there is a common misconception that dialects arise

as a result of the corruption or fragmentation of an earlier standard lan-

guage. Such a standard language had never existed. The standard language

arose out of the dialects of the old kingdoms.

The beginnings of written English

From about the second century the Germanic tribes had made use of an

alphabet of characters called runes, which were mainly designed in straight

lines and were thus suitable for incising with a chisel. Runes were used for

short inscriptions on jewellery and other valuable artifacts, commemora-

tive texts on wood, rocks and stones, and for magical purposes. As Chris-

tianity was introduced to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, a new literacy culture

was introduced with it. The new culture made use of connected texts, and

its language was Latin. There are some interesting overlaps between the

two cultures, for example the Ruthwell Cross is a late runic monument

from the middle of the eighth century, and is incised with runes represent-

ing extracts from the Christian poem The dream of the rood. One runic

panel even represents a phrase of Latin (Sweet, 1978: 103).

The earliest use of English in manuscripts as opposed to inscriptions is

found in glosses, which provided an English equivalent for some of the

words of the Latin text. To make the earliest glosses, the writer had to find

a way of using Latin letters to represent the sounds of English. Some

letters, including <c, d, m, p>, had identifiable English counterparts, and

I . The angle brackets are used to enclose spellings.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/texto-theoriginsoftheenglishlanguage-111124200150-phpapp01/85/Text-The-origins-of-the-English-language-8-320.jpg)

![26 The origins of the English language

so the use of these letters was straightforward. English also had vowel and

consonant sounds which did not exist in Latin, and a means had to be found

to represent them. For the sounds now spelt <th>, the runic character <}>>

was used interchangeably with a new character <d>, and another rune wynn

was used to represent the sound [w]. Another solution for non-Latin sounds

was the use of digraphs. Vowel letters were combined in different ways to

represent the complex vowel sounds of English, for example the digraph

<se> ('ash') was used for the English vowel intermediate between Latin

<a> and <e>. In <ecg> ('edge') the digraph <cg> was used for the con-

sonant [ds]. (The pronunciation of this word has not changed: the conven-

tion <cg> was later replaced by <dge>.)

The same spellings would be used time and time again, and eventually a

convention would develop. The existence of a convention tends to con-

servatism in spelling, for old conventions can be retained even when

pronunciation has changed, or they can be used for another dialect for

which they do not quite fit. For example, the English words <fisc> and

<scip> originally had phonetic spellings and were pronounced [fisk] and

[skip] respectively. The sequence [sk] was replaced in pronunciation by the

single sound [J], so that the words were later pronounced [fij, Jip]. In this

way the spelling <sc> became an arbitrary spelling convention. Spelling

conventions can thus reflect archaic pronunciations, and any close connec-

tion between spoken and written is quickly lost. We still write knee with an

initial <k> not because we pronounce [k] ourselves, but because it was

pronounced in that way when the modern conventions were established

many generations ago in the fifteenth century.

There has always been variation in the pronunciation of English words,

and so the question must be raised as to whose pronunciation was repre-

sented by the spelling. In the first instance, it was more likely that of the

person in charge of a scriptorium than of the individual who prepared the

manuscript. When new spellings were adopted, they would represent the

pronunciation of powerful people: for example, new spellings in the eighth

century presumably represented the English spoken at the Mercian court. It

follows that although we can usually guess what kind of pronunciation is

represented by English spellings, it is far from clear whose pronunciation

this is, and it may not be the pronunciation of any individual person. Second,

while it is possible by examining orthographic variants to work out roughly

where a text comes from, it does not follow that these variants represent the

contemporary speech of the local community. Official languages, in parti-

cular spellings, are not necessarily close to any spoken form, and are

relatively unaffected by subsequent change in the spoken language. The

language of early texts was already far removed from the speech of the

ordinary people of Tamworth or Winchester, much as it is today.

There is a similar problem with respect to grammar. Some later glosses,

for example the Lindisfarne gospels of the mid to late tenth century, take

the form of an interlinear translation of groups of words or a whole text.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/texto-theoriginsoftheenglishlanguage-111124200150-phpapp01/85/Text-The-origins-of-the-English-language-9-320.jpg)