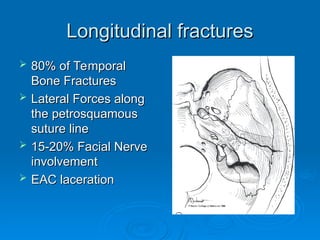

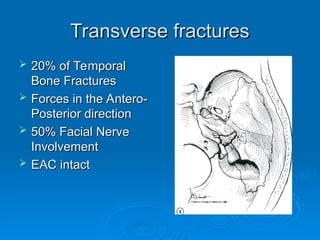

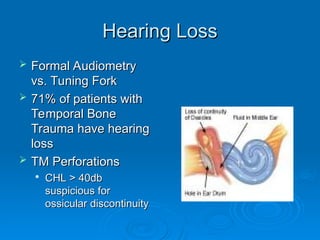

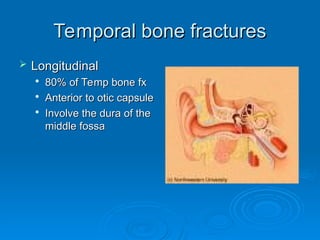

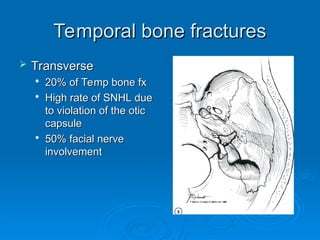

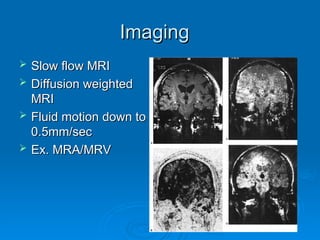

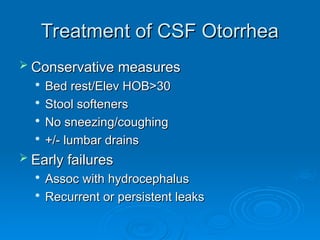

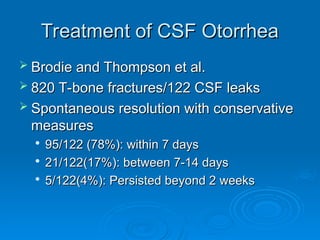

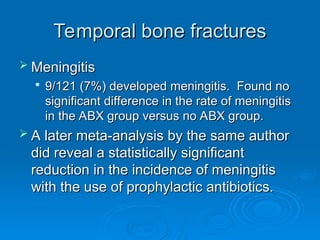

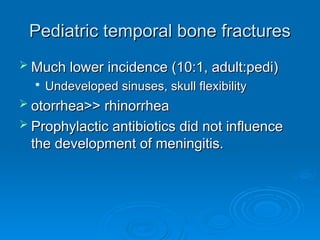

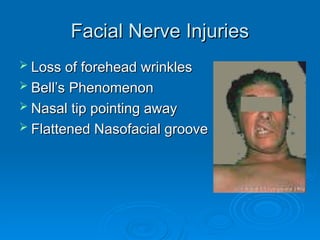

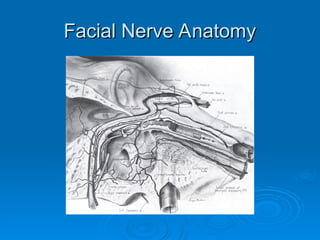

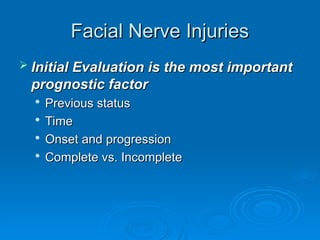

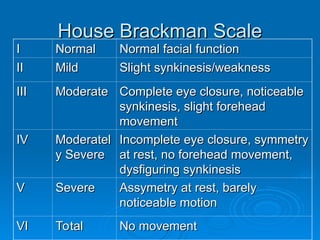

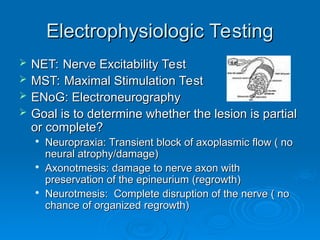

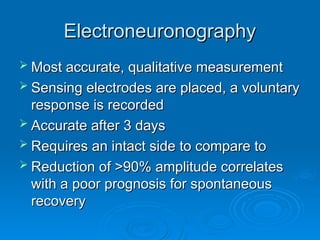

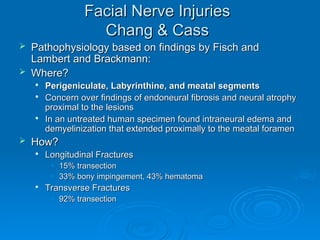

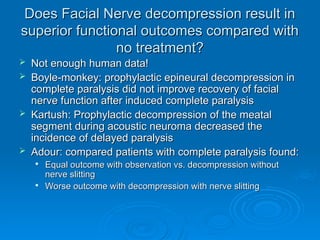

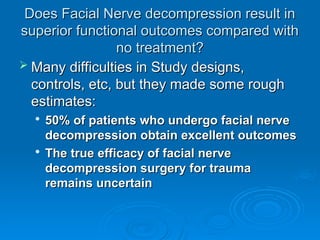

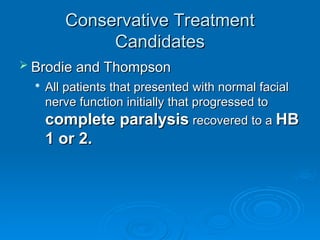

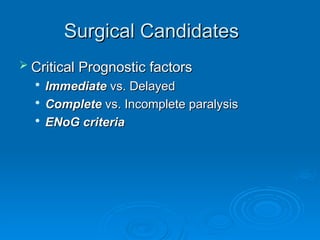

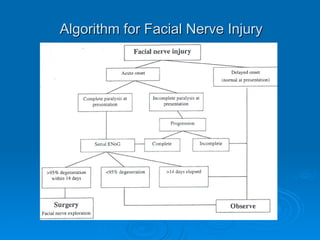

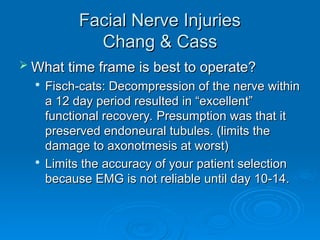

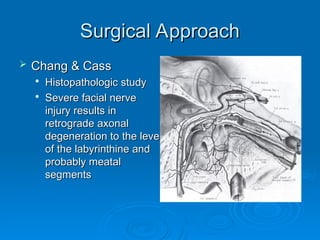

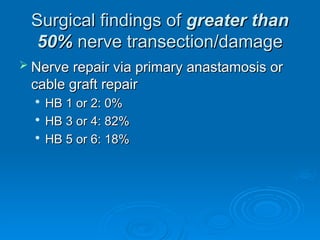

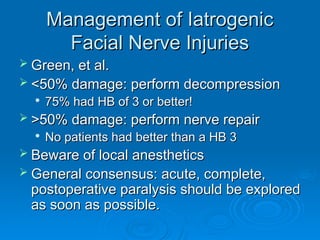

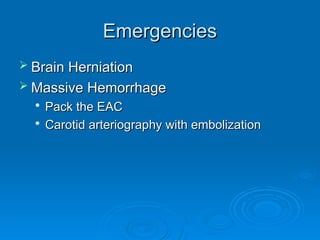

The document discusses temporal bone trauma, its clinical findings, and the importance of anatomical knowledge for diagnosis and management. It covers various causes of trauma, diagnostic methods, and treatment options, highlighting challenges associated with issues like facial nerve injuries and hearing loss. The document emphasizes outcomes based on treatment approaches and the need for thorough evaluation to improve prognoses in affected patients.