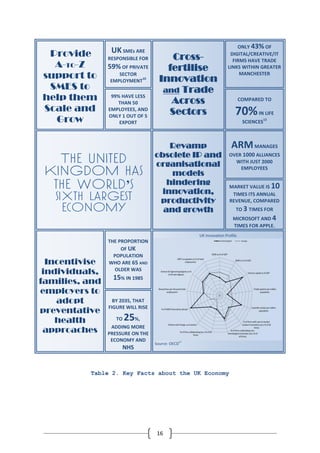

This document summarizes discussions from a series of events on technology ventures. It addresses 21st century paradigms for innovation, new innovation models, and focuses on digital technologies, biotechnology, and healthcare. Key topics discussed include using data and incentives to encourage preventative healthcare, balancing public and private use of health data, and how new firms are driving innovation in genomics and new drug discovery models through collaboration.